Whiteness, Class and Place in Two London Suburbs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bromley Local Studies and Archives Index to Names in the Bromley Poor Law Union Workhouse Creed Registers Surnames Beginning Wi

Bromley Local Studies and Archives Index to names in the Bromley Poor Law Union workhouse Creed Registers Surnames beginning with C 1877-1894 Admitted Name of Discharge Admission Surname Forename(s) Birth Next of Kin address from Creed informant date Reason Year Date year 1891 9 May Cadwell Jane 1871 Ellen, Woodlands, Chase-side, N BRO CE Self 7 Jul 1891 O 1891 19 Oct Campbell John 1889 Mother: Croydon Infirmary BEC CE Police 14 Oct 1891 O 1891 23 Jun Cannon Louisa 1846 SMC CE Self 26 Jun 1891 O 1893 24 May Cannon Lucy 1851 SMC CE Self 29 May 1893 O Mother: 2nd plot, Maple Road, 1893 4 Apr Carlow George 1878 Hestable (Hextable?) nr Swanley CHI CE Self 22 May 1893 Ab 1893 1 Dec Carlow Liberty 1841 Wife: Hearnes Road, St Pauls Cray SPC CE R O 30 Dec 1893 O Brother: Walter, Cherry Orchard 1890 11 Mar Carpenter George 1833 Road, Croydon CUD CE Self 8 Mar 1893 O 1893 17 Mar Carpenter George 1833 BRO CE Self Mrs Fairman, 15 Arthur Road, 1892 8 Jul Carr Charles 1860 Beckenham BEC CE Self 9 Jul 1892 D 1878 24 Jul Carreck Jane 1814 BEC CE Self 10 Jan 1891 D 1887 1 Apr Carreck John 1812 BRO CE Self 25 Jun 1891 D Friend: Mrs Haxell, 7 Sharps 1890 3 Feb Carrington William 1838 Cottage, Bromley BRO CE Self 5 Feb 1890 O Mr Carter, 11 Styles Cottages, St 1892 26 Sep Carter Betsy 1825 Rauls Cray SPC CE R O 8 Oct 1892 O Mr Carter, 1 Oak Terrace, 1891 1 Nov Carter Eliza 1841 Orpington ORP CE R O 2 Nov 1891 O 1891 27 Oct Casinells Dominie ? 1857 CHI CE Self 25 May 1893 D Brother: Lucas, 1 Chislehurst 1890 9 Dec Castle James 1849 Road, Widmore Road, Bromley -

Local Area Map Bus Map

Gipsy Hill Station – Zone 3 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Emmanuel Church 102 ST. GOTHARD ROAD 26 94 1 Dulwich Wood A 9 CARNAC STREET Sydenham Hill 25 LY Nursery School L A L L CHALFORD ROAD AV E N U E L 92 B HAMILTON ROAD 44 22 E O W Playground Y E UPPPPPPERE R L N I 53 30 T D N GREAT BROWNINGS T D KingswoodK d B E E T O N WAY S L R 13 A E L E A 16 I L Y E V 71 L B A L E P Estate E O E L O Y NELLO JAMES GARDENS Y L R N 84 Kingswood House A N A D R SYDEENE NNHAMAMM E 75 R V R 13 (Library and O S E R I 68 122 V A N G L Oxford Circus N3 Community Centre) E R 3 D U E E A K T S E B R O W N I N G L G I SSeeeleyeele Drivee 67 2 S E 116 21 H WOODSYRE 88 1 O 282 L 1 LITTLE BORNES 2 U L M ROUSE GARDENS Regent Street M O T O A U S N T L O S E E N 1 A C R E C Hamley’s Toy Store A R D G H H E S C 41 ST. BERNARDS A M 5 64 J L O N E L N Hillcrest WEST END 61 CLOSE 6 1 C 24 49 60 E C L I V E R O A D ST. -

Core Strategy

APPENDIX 2 AREA PEN PORTRAITS 1 Beckenham Copers Cope & Kangley Bridge 2 Bickley 3 Bromley Common 4 Chislehurst 5 Clock House, Elmers End & Eden Park 6 Cray Valley, St Paul's Cray & St. Mary Cray 7 Crofton and Farnborough 8 Crystal Palace, Penge & Anerley 9 Hayes 10 Keston 11 Mottingham 12 Shortlands, Park Langley & Pickhurst 13 West Wickham & Coney Hall Places within the London Borough of Bromley Ravensbourne, Plaistow & Sundridge Mottingham Beckenham Copers Cope Bromley Bickley & Kangley Bridge Town Chislehurst Crystal Palace Cray Valley, St Paul's Penge and Anerley Cray & St. Mary Cray Shortlands, Park Eastern Green Belt Langley & Pickhurst Clock House, Elmers Petts Wood & Poverest End & Eden Park Orpington, Ramsden West Wickham & Coney Hall & Goddington Hayes Crofton & Farnborough Bromley Common Chelsfield, Green Street Green & Pratts Bottom Keston Darwin & Green Belt Biggin Hill Settlements Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database 2011. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100017661. BECKENHAM COPERS COPE & KANGLEY BRIDGE Character The introduction of the railway in mid-Victorian times saw Beckenham develop from a small village into a town on the edge of suburbia. The majority of dwellings in the area are Victorian with some 1940’s and 50’s flats and houses. On the whole houses tend to have fair sized gardens; however, where there are smaller dwellings and flatted developments there is a lack of available off-street parking. During the later part of the 20th century a significant number of Victorian villas were converted or replaced by modern blocks of flats or housing. Ten conservation areas have been established to help preserve and enhance the appearance of the area reflecting the historic character of the area. -

N47 St. Mary Cray – Bromley

N47 St.MaryCray–Bromley–TrafalgarSquare N47 Sunday night/Monday morning to Thursday night/Friday morning StMaryCrayStation 0005 0035 0105 0135 0205 0235 0305 0335 0405 0435 0505 OrpingtonPond 0009 0039 0110 0140 0210 0240 0310 0340 0410 0440 0510 OrpingtonStationCroftonRoad 0013 0043 0114 0144 0214 0244 0314 0344 0414 0444 0514 PettsWoodStationQueensway 0018 0048 0119 0149 0219 0249 0319 0349 0419 0449 0519 BromleyCommonCrown 0023 0053 0124 0154 0224 0254 0324 0354 0424 0454 0524 BromleySouthStation 0027 0057 0127 0157 0227 0257 0327 0358 0428 0458 0528 BromleyMarketSquare 0030 0100 0130 0200 0230 0300 0330 0401 0431 0501 0532 DownhamBromleyRoad 0035 0105 0135 0205 0235 0305 0335 0406 0437 0507 0538 BellinghamCatfordBusGarage 0039 0109 0139 0209 0239 0309 0339 0410 0441 0512 0543 CatfordBromleyRoad 0041 0111 0141 0211 0241 0311 0341 0412 0443 0514 0545 LewishamHospital 0044 0114 0144 0214 0244 0314 0344 0415 0446 0517 0548 LewishamStationLoampitVale 0048 0118 0148 0218 0248 0318 0348 0419 0451 0522 0553 DeptfordBroadwayChurchStreet 0052 0122 0152 0222 0252 0322 0352 0423 0455 0526 0558 SurreyQuaysStation 0059 0129 0159 0229 0259 0330 0400 0431 0503 0534 0606 BermondseyStation 0102 0132 0202 0232 0302 0333 0404 0435 0507 0538 0610 LondonBridgeSouthwarkCathedral 0108 0138 0208 0238 0308 0339 0411 0442 0514 0546 0618 LudgateCircusLudgateHill 0113 0143 0213 0243 0313 0344 0416 0448 0520 0552 0624 AldwychLawCourts 0115 0145 0215 0245 0315 0347 0419 0451 0523 0555 0627 TrafalgarSquareCharingCrossStn. 0119 0149 0219 0249 0319 0351 0423 0455 -

Grasmere Court, Westwood Hill, London, SE26 £325,000 - £350,000 £350,000 Leasehold

Grasmere Court, Westwood Hill, London, SE26 £325,000 - £350,000 £350,000 Leasehold Share of freehold ( Extended lease Modern fitted kitchen length ) Contemporary three piece bathroom Two double bedrooms suite Purpose built apartment Separate W/C Bright and spacious throughout Free off street parking Excellent decorative order throughout Short walk to Crystal Palace Park 2, Lansdowne Road, Croydon, London, CR9 2ER Tel: 0330 043 0002 Email: [email protected] Web: www.truuli.co.uk Grasmere Court, Westwood Hill, London, SE26 £325,000 - £350,000 £350,000 Leasehold Vendor Comments: "When I began my property search (over 14 years ago), I quickly realised that I couldn’t afford a two bedroom flat in North London. Having explored a few areas in South London, I found my dream flat on the borders of Lewisham, Southwark and Bromley. The flat has two double bedrooms, two storage cupboards, a nice sized lounge and kitchen. It was redecorated (painting/new laminate floors) in Nov 19, while the kitchen was renovated in the summer of 2017. There is access to a communal garden that is shared with Torrington Court but if you fancy larger green spaces, a maze, dinosaurs and a lake, then Crystal Palace Park is a 10min walk. If you fancy somewhere more quieter, then Wells Park and Dulwich Woods are close by. The location is fantastic as there are great transport links, which makes commuting for work or social events really easy. There are several mainline stations that are either a 10-15 min walk or a bus ride away. These are Sydenham & Penge West (for London Bridge, East & West Croydon, Victoria and Highbury & Islington), Crystal Palace (Highbury & Islington, Beckenham Junction, West Croydon, Clapham Junction and Victoria), Sydenham Hill & Penge East (Victoria, Herne Hill and Blackfriars). -

Appendix B List of Site Applicable to the PSPO. All Carriageways

Appendix B List of site applicable to the PSPO. All carriageways, adjoining footpaths and verges in the London Borough of Bromley. All pedestrian areas. All car parks and public vehicle parking areas maintained by the London Borough of Bromley. All alleys, public walks, passageways, bridleways and rights of way that are not in private ownership within the London Borough of Bromley. Equipped playgrounds Alexandra Recreation Ground, Alexandra Road, Penge SE20 Betts Park, Croydon Road, Penge SE20 Biggin Hill Recreation Ground, Church Road, Biggin Hill Blake Recreation Ground, Pine Avenue, West Wickham Burham Close Play Area, Burham Close, Penge SE20 Cator Park, Aldersmead Road, Beckenham Charterhouse Green, Charterhouse Road, Orpington Chelsfield Open Space, Skibbs Lane, Chelsfield Chislehurst Recreation Ground, Empress Drive, Chislehurst Church House Gardens Recreation Ground, Church Road, Bromley Churchfields Recreation Ground, Playground Close, Elmers End Coney Hall Recreation Ground, Addington Road, West Wickham Crease Park, Village Way, Beckenham Croydon Road Recreation Ground, Croydon Road, Beckenham Crystal Palace Park, Thicket Road, Penge SE20 Cudham Lane North Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane North, Green Street Green Cudham Lane South Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane South, Cudham Downe Recreation Ground, High Elms Road, Downe Edgebury Open Space, Imperial Way, Chislehurst Eldred Drive Playground, Eldred Drive, St Mary Cray Elmers End Recreation Ground, Shirley Crescent, Elmers End Farnborough Hill Open Space, High Street, Farnborough -

11 Brockley Rise, Forest Hill, London SE23 1JG Mixed-Use Freehold for Sale View More Information

11 Brockley Rise, Forest Hill, London SE23 1JG Mixed-use freehold for sale View more information... 11 Brockley Rise, Forest Hill, London SE23 1JG Home Description Location Terms View all of our instructions here... III III • Unbroken commercial mixed-use freehold • Period terrace • A1 use • Busy local parade • Requires modernisation • Guide price - £450,000 F/H DESCRIPTION A rare opportunity to purchase an unbroken freehold commercial terrace positioned in a highly popular and sought after area of Forest Hill. The accommodation comprises a ground floor A1 retail shop, which leads to a rear lobby area, kitchen and rear hallway with access to a courtyard. The first floor comprises a bathroom, a separate WC, kitchen / breakfast room and lounge. The top floor comprises two double bedrooms and all accommodation requires complete refurbishment throughout. The rear yard leads to a service road which offers scope for a separate access to the residential uppers. LOCATION The property is positioned in a popular parade which benefits from an abundance of passing pedestrian and vehicular traffic. The B218 Brockley Rise is a main link between the South Circular and Brockley which boasts a number of local bus routes, as well as frequent services towards London, including the 171 which stops at Holborn Station. 30 minute parking bays allow for passing traffic to stop, whilst neighbouring roads offer free all day parking. Honor Oak Park Station is just 0.6 miles away and offers fast train services to London Bridge in approx. 15 minutes. E: [email protected] W: acorncommercial.co.uk 1 Sherman Road, 120 Bermondsey Street, Bromley, Kent BR1 3JH London SE1 3TX T: 020 8315 5454 T: 020 7089 6555 11 Brockley Rise, Forest Hill, London SE23 1JG Home Description Location Terms View all of our instructions here.. -

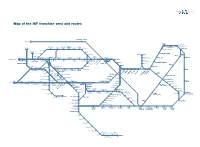

IKF ITT Maps A3 X6

51 Map of the IKF franchise area and routes Stratford International St Pancras Margate Dumpton Park (limited service) Westcombe Woolwich Woolwich Abbey Broadstairs Park Charlton Dockyard Arsenal Plumstead Wood Blackfriars Belvedere Ramsgate Westgate-on-Sea Maze Hill Cannon Street Erith Greenwich Birchington-on-Sea Slade Green Sheerness-on-Sea Minster Deptford Stone New Cross Lewisham Kidbrooke Falconwood Bexleyheath Crossing Northfleet Queenborough Herne Bay Sandwich Charing Cross Gravesend Waterloo East St Johns Blackheath Eltham Welling Barnehurst Dartford Swale London Bridge (to be closed) Higham Chestfield & Swalecliffe Elephant & Castle Kemsley Crayford Ebbsfleet Greenhithe Sturry Swanscombe Strood Denmark Bexley Whitstable Hill Nunhead Ladywell Hither Green Albany Park Deal Peckham Rye Crofton Catford Lee Mottingham New Eltham Sidcup Bridge am Park Grove Park ham n eynham Selling Catford Chath Rai ngbourneT Bellingham Sole Street Rochester Gillingham Newington Faversham Elmstead Woods Sitti Canterbury West Lower Sydenham Sundridge Meopham Park Chislehurst Cuxton New Beckenham Bromley North Longfield Canterbury East Beckenham Ravensbourne Brixton West Dulwich Penge East Hill St Mary Cray Farnigham Road Halling Bekesbourne Walmer Victoria Snodland Adisham Herne Hill Sydenham Hill Kent House Beckenham Petts Swanley Chartham Junction uth Eynsford Clock House Wood New Hythe (limited service) Aylesham rtlands Bickley Shoreham Sho Orpington Aylesford Otford Snowdown Bromley So Borough Chelsfield Green East Malling Elmers End Maidstone -

Beckenham Area Guide ST05.Indd

Your local Proctors branch: Beckenham Why choose us? We’re not just local estate agents, we’re local people too. We combine the same ethos of quality and integrity that George Proctor founded the company on 75 years Did you know? ago, with the very latest technology and marketing techniques to help you with your move. All our team combine decades of knowledge with unrivalled service, and we Our office at ‘Thornton’s won’t stop until you get the home, tenant or buyer you’re looking for. Corner’ is the site of the first British Post Residential sales 6 branches Office, from where the Lettings & management Land & development first airmail was sent. New home sales Market advice MEET YOUR TEAM Chris Wall Ian Davy Resident Partner/Proprietor Manager I have over 30 years experience in the residential I have been an estate agent in Beckenham for property sales sector and joined Proctors in 30 years and enjoy the variety and challenges 1991. I am also a qualified member of the NAEA. that every day brings. In my spare time I enjoy I enjoy the challenges of running the business swimming and long walks in the country followed and working with a dedicated team. by a pub lunch. [email protected] [email protected] Jane Willingham Loraine Knights Senior Negotiator Administrator I have 32 years experience in the property market I have always been part of the property industry in Beckenham and joined Proctors in the early and previously worked at Proctors in Park Langley 1990s. The team refer to me as the ‘encyclopedia before joining the Beckenham branch. -

London Borough of Bromley Local Plan Examination – Matters Statement

WEST & PARTNERS London Borough of Bromley Local Plan Examination – Matters Statement Date 17 November 2017 From: West & Partners on behalf of Dylon 2 Limited and Relta Limited (Objection 134 & 135) Issue 6: Are the policies relating to the Renewal Areas justified, consistent with national policy and The London Plan and will they be effective? _________________________________________________________________ 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 While addressing this Issue and the questions formulated under it, this submission is aimed to support the case for the designation of the Dylon 2 site as a residential development site with associated publicly accessible open space. The evidence that it does not contribute significantly to the MOL is addressed in the submissions under Issue 10 and that it can contribute to meeting the pressing housing needs not addressed by the submission Local Plan. 1.2 The Plan fails to identify the area of Lower Sydenham, as a Renewal Area. This is an area which, together with the neighbouring wards of Bellingham, Whitefoot and Downham (as shown on the map below) in the London Borough of Lewisham, from a socio-economic perspective performs less well against a range of economic, deprivation and housing indicators than LBB averages and as such should be a focus for renewal and improvement. 1.3 The Draft Plan is not therefore in conformity with the requirements of Policy 2.6; 2.7 and 2.8 of the London Plan and accordingly fails this requirement. 1.4 We contend that the Local Plan should identify the area of Lower Sydenham, as a seventh Renewal Area. 1.5 This should be coupled with additional allocations for housing on sustainable, accessible brown field sites close to Lower Sydenham Railway Station. -

Planning Application Design & Access Statement Van-0387

PLANNING APPLICATION DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT VAN-0387 53 PERRY VALE, FOREST HILL, LONDON, SE23 2NE SEPTEMBER 2018 1.0 Contents VAN-0387 – 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE, London Borough of Lewisham Design and Access Statement, July 2018 1.0 Contents 1 2.0 Introduction 2 3.0 Site analysis and Current Building 5 4.0 Description of the proposal 7 5.0 Use and Layout 10 6.0 Heritage Statement 12 7.0 Planning History and Policies 15 8.0 Architectural Character and Materials 15 9.0 Landscaping and Trees 19 10.0 Ecology 19 11.0 Extract, Ventilation and Services 20 12.0 Cycle Storage and Refuse 20 13.0 Sustainability and Renewable Energy Technology 21 14.0 Access & Mobility Statement 21 15.0 Transport, Traffic and parking Statement 22 16.0 Acoustics 22 17.0 Flood Risk 22 18.0 Statement of Community Engagement 23 19.0 Conclusion 24 1 2.0 Introduction VAN-0387 – 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE, London Borough of Lewisham Design and Access Statement, July 2018 This application submission is prepared by db architects on behalf of Vanquish Iconic Developments for the site at 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE. Vanquish are a family-run business and have been creating urban industrial interior designed developments for many years now across South East London. "We are a firm believer that property development should be creative, not made with basic materials to fit the standard criteria of a build. This is reflected in our interiors and exteriors of each finished development. -

Green Chain Walk Section 10

Transport for London.. Green Chain Walk. Section 10 of 11. Beckenham Place Park to Crystal Palace. Section start: Beckenham Place Park. Nearest stations Beckenham Hill . to start: Section finish: Crystal Palace. Nearest stations Crystal Palace to finish: Section distance: 3.9 miles (6.3 kilometres). Introduction. This section runs from Beckenham Place Park to Crystal Palace, a section steeped in heritage, with a Victorian Dinosaur Park at Crystal Palace Park and a rather unusual Edward VIII pillar box at Stumps Hill, made at Carron Ironworks. Directions. If starting at Beckenham Hill station, turn right from the station on to Beckenham Hill Road and cross this at the pedestrian lights. Enter Beckenham Place Park along the road by the gatehouse on your left and use the parallel footpath to Beckenham House Mansion, which is the start of section ten. From Beckenham House Mansion, take the footpath on the other side of the car park and head down to Southend Road. Upon reaching this, turn left and follow the road, crossing over to turn right into Stumps Hill Lane. At the Green Chain major signpost turn left along Worsley Bridge Road. At the T-junction turn right into Brackley Road towards St. Paul's church on the opposite side. Continue along Brackley Road to turn left into Copers Cope Road. Take the first right off Copers Cope Road to pass through the subway under New Beckenham railway station and into Lennard Road. From Lennard Road take the first left into King's Hall Road. Continue along King's Hall Road then turn right between numbers 173 and 175.