CNS COVID-19 Glasgow Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts January 2017 Contents Glasgow City Community Health and Care Centre page 1 North East Locality 2 North West Locality 3 South Locality 4 Adult Protection 5 Child Protection 5 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 5 Addictions 6 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 Children and Families 12 Continence Services 15 Dental and Oral Health 16 Dementia 18 Diabetes 19 Dietetics 20 Domestic Abuse 21 Employability 22 Equality 23 Health Improvement 23 Health Centres 25 Hospitals 29 Housing and Homelessness 33 Learning Disabilities 36 Maternity - Family Nurse Partnership 38 Mental Health 39 Psychotherapy 47 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Psychological Trauma Service 47 Money Advice 49 Nursing 50 Older People 52 Occupational Therapy 52 Physiotherapy 53 Podiatry 54 Rehabilitation Services 54 Respiratory Team 55 Sexual Health 56 Rape and Sexual Assault 56 Stop Smoking 57 Volunteering 57 Young People 58 Public Partnership Forum 60 Comments and Complaints 61 Glasgow City Community Health & Care Partnership Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP), Commonwealth House, 32 Albion St, Glasgow G1 1LH. Tel: 0141 287 0499 The Management Team Chief Officer David Williams Chief Officer Finances and Resources Sharon Wearing Chief Officer Planning & Strategy & Chief Social Work Officer Susanne Miller Chief Officer Operations Alex MacKenzie Clincial Director Dr Richard Groden Nurse Director Mari Brannigan Lead Associate Medical Director (Mental Health Services) Dr Michael Smith -

Port Dundas Fact Sheet

PORT DUNDAS FACT SHEET UNIT 2 SQUARE RIGGER ROW, [email protected] PLANTATION WHARF, BATTERSEA SW11 3TZ +44 20 3475 2553 "Closed 2011 soaring in valUe faster than any P O R T D U N D A S S T O R Y other closed or open distillery. Only closed dUe to a shared internal deal between the monsters Situated at the highest point in the city of Glasgow, Diageo & Edrington (Macallan) to centralise grain built in 1811 at its prime Port Dundas was the largest prodUction" distillery in Scotland, known as the blending powerhouse - Elite Wine & Whisky of Scotland. Port Dundas was one of the founding members of the grain distillers’ conglomerate DCL. Port Dundas later went on to merge with its neighbouring distillery, Cowlairs and another one in 1902, Dundashill. Port Dundas produced grain whisky for many blended whisky brands owned by Diageo such as, Johnnie Walker, J&B, Bell's, Black & White, Vat 69, Haig and White Horse. The site would produce an astonishing 39 million litres of spirit each year before it was shut indefinitely. Sadly after a century of distilling, in 2010 Diageo made the decision to focus their efforts on grain production and expaned Cameronbridge side, and in 2011 production ceased and the site was demolished. Old bottlings can still be found, however, making this whisky rare and special. T I M E L I N E 1811: Port Dundas is founded next to the Forth & 1903 The Distillery catches fire Clyde Canal 1914: The distillery is rebuilt with drum maltings c1832: A Coffey still is installed 1916: Another fire occurs at the distillery -

Taxi School 2021 Section 3 SECTION L INDUSTRIAL ESTATES TAXI SCHOOL

Taxi School 2021 Section 3 SECTION L INDUSTRIAL ESTATES TAXI SCHOOL Anniesland Netherton Rd Spencer St Atlas Edgefauld Rd Haig St Blochairn Blochairn Rd Seimens St Balmore Glentanner Rd Strathmore Rd Carntyne Carntynehall Rd Myreside St Craigton Barfillan Dr Crosslee St Darnley Woodneuk Rd Nitshill Rd Dawsholm Dalsholm Rd Maryhill Rd Dixon Blazes Lawmoor St Caledonia Rd Drumchapel Dalsetter Ave Garscadden Rd Gt Western Retail Park Gt Western Rd Dunreath Ave Hillington Hillington Rd Queen Elizabeth Ave Kinning Park Paisley Rd Seaward St Museum Business Park Woodhead Rd Wiltonburn Rd Oakbank Garscube Rd Barr St Queenslie Stepps Rd Edinburgh Rd Springburn (St Rollox Industrial Park) Springburn Rd St Rollox Brae Thornliebank Nitshill Rd Speirsbridge Rd Whiteinch South St Dilwara Ave page one SECTION M PUBLIC HALLS & COMMUNITY CENTRES Central Halls Maryhill Rd Hopehill Rd City Halls (Old Fruit Market) Albion St Blackfriars St Couper Institute Clarkston Rd Struan Rd Dixon Halls Cathcart Rd Dixon Ave Henry Wood Hall Claremont St Berkley St Kelvin Hall Argyle St Blantyre St Langside Halls Langside Ave Pollokshaws Rd McLellan Galleries Sauchiehall St Rose St Old Govan Town Hall Summertown Rd Govan Rd Partick Burgh Hall Burgh Hall St Fortrose St Pollokshaws Burgh Hall Pollokshaws Rd Christian St Pollokshields Burgh Hall Glencairn Rd Dalziel Ave Royal Concert Hall Sauchiehall St West Nile St Shettleston Halls (fire damaged) Wellshot Rd Ardlui St Trades House/ Hall Glassford St Garth St Woodside Halls (Capoeira Senzala) Glenfarg St Clarendon St Claremont -

PORT DUNDAS TRADING ESTATE North Canal Bank Street, Glasgow, G4 9XP

TO LET LIGHT INDUSTRIAL UNITS PORT DUNDAS TRADING ESTATE North Canal Bank Street, Glasgow, G4 9XP Key Highlights • Light industrial units with availability • The units provide an eaves height of between 1,905 and 4,317 sq ft approximately 6m, which allows for good storage capacity if racking is installed • Within 1.6 kilometres (1 mile) of Glasgow City Centre and less than 1 kilometre • Communal parking and spacious yard area is (0.6 miles) from junction 16 of M8 motorway provided to the rear • Electrically operated roller shutter loading • Circa 1,600 new homes, a school, retail and doors commercial facilities are currently being developed on the two nearby development sites – Dundas Hill and Sighthill SAVILLS GLASGOW 163 West George Street Glasgow G2 2JJ +44 (0) 141 248 7342 savills.co.uk North Canal Bank Street Yard / Parking Location Accommodation The premises are located on North Canal Bank Street in Units are available between 176.98 - 401.06 sq m (1,905 - the Port Dundas area of Glasgow, north of the M8. Port 4,317 sq ft). Dundas Trading Estate offers superb connectivity with Ordnance Survey © Crown Copyright 2019. All Rights Reserved. J16 of the M8 situatedLicence 0.6 number miles 100022432 to the south. Plotted Scale - 1:1250. Paper Size - A4 Energy Performance The location benefits from good public transport links EPCs are available on request. with multiple bus routes operating nearby offering services to the city centre and Queen Street station is Rateable Value situated 1 mile to the south west. The Trading Estate The ingoing tenant will be responsible for the payment benefits from good local amenity being in close of local authority rates in the usual manner. -

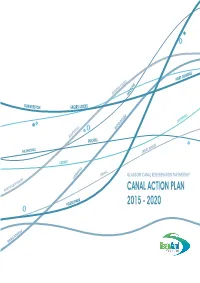

NEW PDF READY F&C DEC 2014.Pmd

S DUNDA N PORT TO SUMM QUEENS CROSS IL ERSTON M SPEIRS LOCKS LL HI ILL RY HTH MA WOODSIDE SIG GILSHOCHILL RUCHILL CADDER SPEIRS WHARF LL DE HI INSI B ELV AM ILL TH K L FIRH NOR GLASGOW CANAL REGENERATION PARTNERSHIP CANAL ACTION PLAN RK POSSILPA 2015 - 2020 ILL NH ILTO HAM 1 FORTH & CLYDE CANAL ACTION PLAN 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION VISION AND PRINCIPLES PLANNING CONTEXT THE CANAL CORRIDOR IN CONTEXT Heritage Asset Communities - character Connectivity & Movement Drainage Town and Neighbourhood Centres Environment, Leisure and Art ACTION PLAN Strategic Projects Maryhill Locks Spiers Locks Port Dundas Applecross - Firhill Communication / Engagement Strategy CONTACT DETAILS 3 FORTH & CLYDE CANAL ACTION PLAN INTRODUCTION This Canal Action Plan (CAP) outlines the regeneration approach and proposed activity along the Glasgow Canal corridor over the next 5 years (2015-2020). The Plan provides an action programme to drive, direct and align regeneration activity in the canal corridor and its neighbouring communities that will be taken forward by the Glasgow Canal Regeneration Partnership in close collaboration with other public, private and community sector partners. cultural and arts organisations, improvement to within the canal corridor, in order to establish The Glasgow Canal Regeneration Partnership paths and the environment - that have started new regeneration priorities for moving forward. (GCRP) is a partnership of Glasgow City to reinvigorate and reconnect communities Following a period of local stakeholder Council, Scottish Canals, and their with the canal. In so doing, the former consultation during summer 2014 the actions development partners ISIS Waterside perception of the canal as an undesirable have been refined. -

Glasgow City Council Housing Development Committee Report By

Glasgow City Council Housing Development Committee Report by Director of Development and Regeneration Services Contact: Jennifer Sheddan Ext: 78449 Operation of the Homestake Scheme in Glasgow Purpose of Report: The purpose of this report is to seek approval for priority groups for housing developments through the new Homestake scheme, and for other aspects of operation of the scheme. Recommendations: Committee is requested to: - (a) approve the priority groups for housing developments through the new Homestake scheme; (b) approve that in general, the Council’s attitude to whether the RSL should take a ‘golden share’ in Homestake properties is flexible, with the exception of Homestake development in ‘hotspot’ areas where the Housing Association, in most circumstances, will retain a ‘golden share’; (c) approve that applications for Homestake properties should normally be open to all eligible households, with preference given to existing RSL tenants to free up other existing affordable housing options; (d) approve that net capital receipts to RSLs through the sale of Homestake properties will be returned to the Council as grant provider to be recycled in further affordable housing developments. Ward No(s): Citywide: Local member(s) advised: Yes No Consulted: Yes No PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING: Any Ordnance Survey mapping included within this Report is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function to make available Council-held public domain information. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey Copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/map data for their own use. The OS web site can be found at <http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk> . -

North West Glasgow Directory

Glasgow Citywide Directory This directory gives information about third sector organisations and projects working with children, young people and families throughout Glasgow. It is a work in progress and more organisations will be added. November 2019 The Everyone’s Children project was set up to support and promote third sector organisations in Glasgow that provide services to children, young people and families. The project is funded by the Scottish Government and works in partnership with statutory partners and the third sector. It aims to: • Develop and support the local third sector capacity to deliver Glasgow Wide wellbeing outcomes. • Ensure third sector contributions to Children’s Services are valued North East and strengthened North West • Share learning and best practice through training and events. South The Everyone’s Children project provides a practical range of support to ensure that the third sector contribution is effectively integrated into planning of services for children and families. The project has helped to Contact: Suzie Scott raise awareness of GIRFEC, map the contribution of the third sector in Telephone: 0141 332 2444 Glasgow, share learning, and support organisations through capacity Email: [email protected] building work. The Children, Young People and Families Citywide Forum provides a strong and co-ordinated voice to partner agencies that influence Children’s Services in Glasgow. The Forum aims to: • consult, agree and support representation on behalf of the sector on priority issues • actively represent forum membership in city wide multi-agency Glasgow Wide planning • provide guidance and support to the Third Sector North East • gather and co-ordinate views on behalf of the Forum North West • promote good practice through shared learning South Membership The Forum is open to all third sector organisations that provide services to Children, Young People and Families in Glasgow. -

Glasgow Wide Schools Directory

Glasgow Wide Schools Directory This directory gives information about third sector organisations and projects working with children and young people of school age throughout Glasgow. It is intended to provide schools with information on third sector services they may wish to access. It is a work in progress and more organisations will be added. January 2020 The Everyone’s Children project was set up to support and promote third sector organisations in Glasgow that provide services to children, young people and families. The project is funded by the Scottish Government and works in partnership with statutory partners and the third sector. It aims to: • Develop and support the local third sector capacity to deliver Glasgow Wide wellbeing outcomes. • Ensure third sector contributions to Children’s Services are valued North East and strengthened North West • Share learning and best practice through training and events. South The Everyone’s Children project provides a practical range of support to ensure that the third sector contribution is effectively integrated into planning of services for children and families. The project has helped to Contact: Suzie Scott raise awareness of GIRFEC, map the contribution of the third sector in Telephone: 0141 332 2444 Glasgow, share learning, and support organisations through capacity Email: [email protected] building work. The Children, Young People and Families Citywide Forum provides a strong and co-ordinated voice to partner agencies that influence Children’s Services in Glasgow. The Forum aims to: • consult, agree and support representation on behalf of the sector on priority issues • actively represent forum membership in city wide multi-agency Glasgow Wide planning • provide guidance and support to the Third Sector North East • gather and co-ordinate views on behalf of the Forum North West • promote good practice through shared learning South Membership The Forum is open to all third sector organisations that provide services to Children, Young People and Families in Glasgow. -

Notice Is Hereby Given That the Scottish Ministers in Exercise of The

ROADS (SCOTLAND) ACT 1984 THE ACQUISITION OF LAND (AUTHORISATION PROCEDURE) (SCOTLAND) ACT 1947 . THE M8.,M73, M74 (NETWORK IMPROVEMENTS) SPECIAL ROAD SCHEME COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 200[ ] Notice is hereby given that the Scottish Ministers in exercise of the powers conferred by the above mentioned Acts, on the Fifth day of August 2008, prepared the above mentioned Compulsory Purchase Order which affects the land described in the Schedule hereto for the purpose of (a) improving that part of the M8/A8 Edinburgh- Greenock Trunk Road between Easterhouse, Glasgow and Baillieston, Glasgow, the M73 Maryville-Mollinsburn Trunk Road between Maryville~ Glasgow and Baillieston, Glasgow, the M74/A74(M) Glasgow-Carlisle Trunk Road between Carmyle, Glasgow and Hamilton, South Lanarkshire and (b) constructing new roads and infrastructure associated with that improvement. The Order is about to be made and comes into operation only if made. If the Order is made, a conveyance registered in implement of the Order may vary or extinguish rights to enforce real burdens and servitudes affecting the land. A copy of the Order and of the map referred to therein have been deposited at: The offices of Transport Scotland, Buchanan House, 58 Port Dundas Road, Glasgow G4 OHF;'the offices of. Glasgow City Council, City Chambers, George Square, Glasgow G2 IDU; the offices of North Lanarkshire Council, Municipal Buildings, Kildonan Street, Coatbridge ML5 3BT; the offices of North Lanarkshire Council; Civic Centre, P.O. Box 14, Motherwell MLl 1TW; the offices of South -

Glasgow’S Canals Unlocked

glasgow’s canals unlocked explore the story Introduction welcome to glasgow’s canals Visit the Canals Glasgow’s Canals: A Brief History Boats at Spiers Wharf Walking or cycling along the towpaths will Both the Forth & Clyde and Monkland canals industries fl ourishing between its gateways at give you a fascinating insight into the rich were hugely infl uential in the industrial and Grangemouth on the East coast and Bowling history and ongoing renaissance of the Forth social growth of the city two hundred years on the West coast, as well as along the three & Clyde and Monkland canals as they wind ago. Today, they are becoming important and mile spur into Glasgow. through the City of Glasgow. relevant once more as we enjoy their heritage, the waterway wildlife and the attractive, By the mid 19th century, over three million There are fi ve sections following the towpath traffi c-free, green open space of the towpaths. tonnes of goods and 200,000 passengers of the Forth & Clyde Canal described here were travelling on the waterway each year and from west to east, from Drumchapel towards The idea of connecting the fi rths of Forth and bankside industries included timber and paper the centre of Glasgow. Clyde by canal was fi rst mooted in 1724 by mills, glassworks, foundries, breweries and the author of Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe. distilleries (including the biggest in the world You can walk or cycle them individually, or join Nearly 45 years later, the advance of innovation at the time at Port Dundas). two or more together to enjoy a longer visit. -

Boer War Burgesses

War in South Africa - Appointed Burgesses City of Glasgow Date Rank Name Middle Surname Occupation Address Battalion 1-Feb-1900 Stewart Adam Traveller 85 Leslie Street Glasgow 3rd Glasgow Yeomanry 21-Feb-1901 William Adam 24 Dixon Street, Crosshill Scottish National Red Cross Hospital 5-Mar-1903 W B Adams 26 Wolseley Street, Glasgow Imperial Yeomanry 5-Sep-1900 David Adamson Printer 200 Main Street Anderston Glasgow 19th Volunteer Service Co- Royal Army Medical Corps 1-Feb-1900 Alexander Aitken Plasterer 5 Mossbank Place Uddingston 2nd Volunteer Service Company-Scottish Rifles 5-Mar-1903 George Evans Aitken 6 Sutherland Terrace, Glasgow Imperial Yeomanry 1-Feb-1900 James Aitken Insurance Agent Glenbank House Lenzie 3rd Glasgow Yeomanry 28-Jun-1900 James Aitken 30 Raeberry Street Glasgow 16th Volunteer Service Co- Imperial Yeomanry 1-Feb-1900 John Russell Aitken Law Clerk 2 Woodlands Terrace Glasgow 1st Volunteer Service Company H.L.I. 21-Feb-1901 John Aitken M.B, Ch. B Maternity Hospital, Glasgow Scottish National Red Cross Hospital 21-Feb-1901 Arthur Alcock 31 Garngad Street, Glasgow Volunteer Service Company-Scottish Rifles 21-Feb-1901 David Shanks Alexander 9 Kilmaining Terrace, Cathcart Volunteer Service Company-Scottish Rifles 1-Feb-1900 Andrew Neilson Alexander jnr Insurance Broker Winningmore Langside Glasgow 3rd Glasgow Yeomanry 21-Feb-1901 Herbert Allan 24 Lochiel Street, Glasgow Scottish National Red Cross Hospital 1-Feb-1900 Henry Allen Clerk 104 North Hanover Street Glasgow 2nd Volunteer Service Company-Scottish Rifles 1-Feb-1900 -

Transporting Scotland's Trade Table of Contents

transport.gov.scot Transporting Scotland's Trade Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 3. Scotland’s Trade ......................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Exports .................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 Imports .................................................................................................................. 9 3.3 Tourism ............................................................................................................... 11 4. Transporting Scotland’s Freight ................................................................................ 12 4.1 Key Transport Gateways and Networks .............................................................. 13 4.2 Air Freight ........................................................................................................... 14 4.3 Water Freight ...................................................................................................... 16 4.4 Road Connectivity ............................................................................................... 18 4.5 Rail Connectivity ................................................................................................. 19 5. Scotland’s