Mandatory AIDS Testing in Professional Team Sports) Paul M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lakers Hold Off Celtics U.S. Blames Noriega for Aide's Death

Voice Repeats Tougher MHS students Simsbury again wins Canada cracks down begin newspapei/3 MHS wrestling toumey/9 on illegal fishing/7 mianrlipatpr I m l i ■My ■ - f- > , . Monday, Dec. 18,1989 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm Newsstand Price: 35 Cents HrralJi MHS boys basketball ‘Good faith’ inexperienced group will save town U.S. blames space penalty SPORTS page 47 By Rick Santos Manchester Herald Noriega for It is unlikely the state will seek legal action against the town for not conforming to statutes for safe Lakers hold off Celtics storage of records, said the state’s acting public records administrator aide’s death today. NBA Roundup Although the town is rapidly ap WASHINGTON (AP) — himself who has encouraged this proaching a Jan. 5 deadline to sub Panamanian ruler Manuel Antonio kind of lawlessness. His own con mit to the state an acceptable plan Noriega “sets an example of cruelty duct sets an example of cruelty and and brutality” in his country, the brumlity. The lack of discipline and BOSTON (AP) — James Worthy led a long-range for bringing record storage up to Bush administration says in control in the Panamanian Defense shooting attack with 28 points Friday night as the Los code, acting Public Records Ad Forces is further evidence that Angeles Lakers broke open a close game with a 12-0 run ministrator Eunice DiBella said that denouncing the weekend killing of a U.S. officer in Panama. Panama is a country without a at the start of the fourth period in a 119-110 victory over from her discussions with Town government,” Cheney said. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

C Ool L Eafstakecriticalvicto Ry Y

The Prince George Citizen - Wednesday, February 16,1994 - 15 S p o r t s HI l' 7'". NBA PLEA BARGAIN ENDS ORDEAL Colts help out Kings < The Cranbrook Colts did the 4 t • • t Prince George Spruce Kings a big B o n i t a k e s favor Tuesday — they beat the BRIEFLY visiting Grande Prairie Chiefs. t o k e n f i n e Four goals in the first period Sunday at the Otway Road Ski helped the .Colts beat Grande Trails in Prince George. Prairie 6-4,’4 keeping the Chiefs Manhard, of 100 Mile House, a n g r y i n h o c k e y four points behind the Spruce finished the men’s event in a time Kings in the race for second place of one hour, one minute three sec d e a t h c a s e in the Rocky Mountain Junior onds, while McGaughey of Prince a t l a z y Hockey League’s Pcace-Cariboo George won the women’s event in AOSTA, Italy (CP) — Jim Division. a time of 1:19.42. Boni, a hockey player brought to Dustin Kelley and Darren Re Diana Thomson finished second trial for causing the death of an eves each scored twice and as to McGaughey in senior women’s K n i c k s opponent during a game, pleaded sisted on two others for the Colts, cvenL while Brien McGaughey guilty today to a reduced man who climbed back within four was second to Manhard. -

USA Basketball Men's Pan American Games Media Guide Table Of

2015 Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Camp Media Guide Colorado Springs, Colorado • July 7-12, 2015 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Schedule Team Training Camp Staffing Tuesday, July 7 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games Team Staff Head Coach: Mark Few, Gonzaga University July 8 Assistant Coach: Tad Boyle, University of Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Assistant Coach: Mike Brown 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Athletic Trainer: Rawley Klingsmith, University of Colorado Team Physician: Steve Foley, Samford Health July 9 8:30-10 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Court Coaches Jason Flanigan, Holmes Community College (Miss.) July 10 Ron Hunter, Georgia State University 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Mark Turgeon, University of Maryland 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II July 11 2015 USA Pan American Games 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Support Staff 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Michael Brooks, University of Louisville July 12 Julian Mills, Colorado Springs, Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Will Thoni, Davidson College 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II USA Men’s Junior National Team Committee July 13 Chair: Jim Boeheim, Syracuse University NCAA Appointee: Bob McKillop, Davidson College 6-8 p.m. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

The BG News October 7, 1993

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-7-1993 The BG News October 7, 1993 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 7, 1993" (1993). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5584. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5584 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. <? The BG News Thursday, October 7, 1993 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 76, Issue 31 Briefs Weather Basketball's greatest ever -- done APPMWMutEHo Get out the shorts and MJ: nothing more to prove sunglasses: Sunny and warm Thurs- The Associated Press glitziest attraction, and mil- day with a high in the upper lions of fans without the hero 70s and southwest winds 10 who redefined standards of ex- to 20 mph. Thursday night DEERFTELD, III. - Michael cellence. will be partly cloudy with a Jordan, basketball's greatest Jordan's departure at the top low SO to 55. player, announced Wednesday of his game occurred during a that he was retiring after nine year of unprecedented success seasons in the NBA, saying he - and personal tragedy. He led Inside the News "had reached the pinnacle of his Chicago Bulls to a third- my career" and had nothing straight NBA championship, University officials tell of else to prove. -

1988-89 Fleer Basketball Checklist

1 988 FLEER BASKETBALL CARD SET CHECKLI ST+A1 1 Antoine Carr 2 Cliff Levingston 3 Doc Rivers 4 Spud Webb 5 Dominique Wilkins 6 Kevin Willis 7 Randy Wittman 8 Danny Ainge 9 Larry Bird 10 Dennis Johnson 11 Kevin McHale 12 Robert Parish 13 Tyrone Bogues 14 Dell Curry 15 Dave Corzine 16 Horace Grant 17 Michael Jordan 18 Charles Oakley 19 John Paxson 20 Scottie Pippen 21 Brad Sellers 22 Brad Daugherty 23 Ron Harper 24 Larry Nance 25 Mark Price 26 John Williams 27 Mark Aguirre 28 Rolando Blackman 29 James Donaldson 30 Derek Harper 31 Sam Perkins 32 Roy Tarpley 33 Michael Adams 34 Alex English 35 Lafayette Lever 36 Blair Rasmussen 37 Dan Schayes 38 Jay Vincent 39 Adrian Dantley 40 Joe Dumars 41 Vinnie Johnson 42 Bill Laimbeer Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Dennis Rodman 44 John Salley 45 Isiah Thomas 46 Winston Garland 47 Rod Higgins 48 Chris Mullin 49 Ralph Sampson 50 Joe Barry Carroll 51 Eric Floyd 52 Rodney McCray 53 Akeem Olajuwon 54 Purvis Short 55 Vern Fleming 56 John Long 57 Reggie Miller 58 Chuck Person 59 Steve Stipanovich 60 Wayman Tisdale 61 Benoit Benjamin 62 Michael Cage 63 Mike Woodson 64 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar 65 Michael Cooper 66 A.C. Green 67 Magic Johnson 68 Byron Scott 69 Mychal Thompson 70 James Worthy 71 Dwayne Washington 72 Kevin Williams 73 Randy Breuer 74 Terry Cummings 75 Paul Pressey 76 Jack Sikma 77 John Bagley 78 Roy Hinson 79 Buck Williams 80 Patrick Ewing 81 Sidney Green 82 Mark Jackson 83 Kenny Walker 84 Gerald Wilkins 85 Charles Barkley 86 Maurice Cheeks 87 Mike Gminski 88 Cliff Robinson 89 Armon -

All-Time Roster

ALL-TIME ROSTER All-Time Roster Brad Daugherty was a five-time NBA All-Star and remains the only Cavalier to ever average 20 points and 10 rebounds in a single season (1990-91, 1991-92, 1992-93). Cavaliers All-Time Roster DENG ADEL Height: 6’7” Weight: 200” Born: February 1, 1997 (Louisville ‘18) Signed a Two-Way contract on January 15, 2019. YEAR GP MIN FGM FGA FG% FTM FTA FT% OR DR TR AST PF-D STL BLK PTS PPG 2018-19 19 194 11 36 .306 4 4 1.000 3 16 19 5 13-0 1 4 32 1.7 Three-point field goals: 6-23 (.261) GARY ALEXANDER Height: 6’7” Weight: 240 Born: November 1, 1969 (South Florida ’92) Signed as a free agent, March 23, 1994. YEAR GP MINS FGM FGA FG% FTM FTA FT% OR DR TR AST PF-D STL BS PTS PPG 1993-94 7 43 7 12 .583 3 7 .429 6 6 12 1 7-0 3 0 17 2.4 LANCE ALLRED Height: 6’11” Weight: 250 Born: February 2, 1981 (Weber State ‘05) Signed as a free agent by the Cavaliers on April 4, 2008 and signed 10-day contracts on March 13 and March 25, 2008. YEAR GP MINS FGM FGA FG% FTM FTA FT% OR DR TR AST PF-D STL BS PTS PPG 2007-08 3 10 1 4 .250 1 2 .500 0 1 1 0 1-0 0 0 3 1.0 JOHN AMAECHI Height: 6’10” Weight: 270 Born: November 26, 1970 (Penn State ’95) Signed as a free agent, October 5, 1995. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Dominique Wilkins

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Dominique Wilkins Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Wilkins, Dominique, 1960- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Dominique Wilkins, Dates: October 5, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 5 uncompressed MOV digital video files (1:49:40). Description: Abstract: Basketball player Dominique Wilkins (1960 - ) played for the Atlanta Hawks for most of his career. He was also a nine-time NBA All-Star, and inducted into The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2006. Wilkins was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2016, in Atlanta, Georgia. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_070 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Basketball player Dominique Wilkins was born on January 12, 1960 in Paris, France to John Wilkins, a sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, and Gertrude Baker. Wilkins had seven siblings, including Gerald Wilkins, who also played professional basketball. Dominique Wilkins’ family eventually settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he began playing basketball on the playground while attending Dunbar High School. As a high school sophomore, Wilkins relocated to Washington, North Carolina and played at Washington High School. There, he won two North Carolina Class 3-A Championships in 1978 and 1979, and was won two North Carolina Class 3-A Championships in 1978 and 1979, and was voted as state MVP in both seasons. Wilkins enrolled at the University of Georgia, where he played basketball for three years, and was awarded as SEC Player of the Year in 1981. -

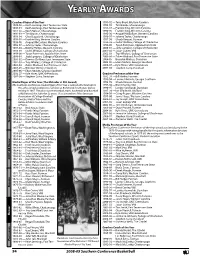

Yearly Awards

YEARLY AWARDS YEARLY AWARDS Coaches Player of the Year 1991-92 — Terry Boyd, Western Carolina 1989-90 — Keith Jennings, East Tennessee State 1992-93 — Tim Brooks, Chattanooga 1990-91 — Keith Jennings, East Tennessee State 1993-94 — Frankie King, Western Carolina 1991-92 — Keith Nelson, Chattanooga 1994-95 — Frankie King, Western Carolina 1992-93 — Tim Brooks, Chattanooga 1995-96 — Anquell McCollum, Western Carolina 1993-94 — Chad Copeland, Chattanooga 1996-97 — Johnny Taylor, Chattanooga 1994-95 — Frankie King, Western Carolina 1997-98 — Chuck Vincent, Furman 1995-96 — Anquell McCollum, Western Carolina 1998-99 — Sedric Webber, College of Charleston NTRODUCTION I 1996-97 — Johnny Taylor, Chattanooga 1999-00 — Tyson Patterson, Appalachian State 1997-98 — Bobby Phillips, Western Carolina 2000-01 — Jody Lumpkin, College of Charleston 1998-99 — Sedric Webber, College of Charleston 2001-02 — Jason Conley, VMI 1999-00 — Tyson Patterson, Appalachian State 2002-03 — Troy Wheless, College of Charleston 2000-01 — Jody Lumpkin, College of Charleston 2003-04 — Zakee Wadood, East Tennessee State 2001-02 — Dimeco Childress, East Tennessee State 2004-05 — Brendan Winters, Davidson 2002-03 — Troy Wheless, College of Charleston 2005-06 — Elton Nesbitt, Georgia Southern 2003-04 — Zakee Wadood, East Tennessee State 2006-07 — Kyle Hines, UNC Greensboro 2004-05 — Brendan Winters, Davidson 2007-08 — Stephen Curry, Davidson 2005-06 — Elton Nesbitt, Georgia Southern 2006-07 — Kyle Hines, UNC Greensboro Coaches Freshman of the Year ONFERENCE C 2007-08 — Stephen Curry, Davidson 1992-93 — Bill Harder, Furman 1993-94 — Lonnie Edwards, Georgia Southern ERN Media Player of the Year (The Malcolm U. Pitt Award) 1994-95 — Chuck Vincent, Furman H The Southern Conference media Player of the Year is named after Malcolm U. -

Cavaliers Assistant Coaches Cavaliers General

All-Time Coaches Record All-Time Coaches & General Managers Coach Years Record Pct. Coach Years Record Pct. Bill Fitch 1970-79 304-434 .412 John Lucas 2001-03 37-87 .298 Stan Albeck 1979-80 37-45 .451 Keith Smart 2002-03 9-31 .225 Bill Musselman 1980-82 27-67 .287 Paul Silas 2003-05 69-77 .473 Chuck Daly 1981-82 9-32 .220 Brendan Malone 2005 8-10 .444 Don Delaney 1981-82 7-21 .250 Mike Brown 2005-10, Bob Kloppenburg 1981-82 0-1 .000 2013-14 305-187 .620 Tom Nissalke 1982-84 51-113 .311 Byron Scott 2010-2013 64-166 .386 George Karl 1984-86 61-88 .409 David Blatt 2014-2016 83-40 .675 Gene Littles 1985-86 4-11 .267 Tyronn Lue 2016-2018 128-83 .607 Lenny Wilkens 1986-93 316-258 .551 Larry Drew 2018-2019 19-57 .250 Mike Fratello 1993-99 248-212 .539 John Beilein 2019-2020 14-40 .259 Randy Wittman 1999-2001 62-102 .378 J .B . Bickerstaff 2020-present 5-6 .455 Cavaliers Assistant Coaches Jim Lessig . 1970-71 Richie Adubato . 1993-94 Mark Osowski . 2003-04 Bernie Bickerstaff . 2013-2014 Jimmy Rodgers . 1971-79 Jim Boylan . 1993-97 Stephen Silas . 2003-05 Igor Kokoskov . 2013-2014 Morris McHone . 1979-80, Ron Rothstein . 1993-99 Brendan Malone . 2004-05 Bret Brielmaier . 2013-2016 1984-86 Sidney Lowe . 1994-99 Wes Wilcox . 2005 Jim Boylan . 2013-2018 Larry Creger . 1980-81 Marc Iavaroni . 1997-99 Kenny Natt . 2004-07 Tyronn Lue . 2014-2016 Gerald Oliver . -

June 1998: NBA Draft Special

“Local name, national Perspective” $4.95 © Volume 4 Issue 8 1998 NBA Draft Special June 1998 BASKETBALL FOR THOUGHT by Kris Gardner, e-mail: [email protected] Garnett—$126 M; and so on. Whether I’m worth the money Lockout, Boycott, So What... or not, if someone offered me one of those contract salaries, ime is ticking by patrio- The I’d sign in a heart beat! (Right and July 1st is tism in owners Jim McIlvaine!) quickly ap- 1992 want a In order to compete with proaching. All when hard the rising costs, the owners signs point to the owners he salary cap raise the prices of the tickets. locking out the players wore with no Therefore, as long as people thereby delaying the start of the salary ex- buy the tickets, the prices will the free agent signing pe- Ameri- emptions continue to rise. Hell, real riod. As a result of the im- can similar to people can’t afford to attend pending lockout, the players flag the NFL’s games now; consequently, union has apparently de- draped salary cap corporations are buying the cided to have the 12 mem- over and the seats and filling the seats with bers selected to represent the his players suits. USA in this summer’s World Team © The players have wanted Championships in Greece ...the owners were rich when they entered the league and to get rid of the salary cap for boycott the games. Big deal there aren’t too many legal jobs where tall, athletic, and, in years and still maintain that and so what.