Mr Andrew Aston and Others V Chief Constable of Greater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electoral Review of Salford City Council

Electoral review of Salford City Council Response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s consultation on Warding Patterns August 2018 1 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Salford in 2018 has changed dramatically since the city’s previous electoral review of 2002. Salford has seen a turnaround in its fortunes over recent years, reversing decades of population decline and securing high levels of investment. The city is now delivering high levels of growth, in both new housing and new jobs, and is helping to drive forward both Salford’s and the Greater Manchester economies. 1.2 The election of the Greater Manchester Mayor and increased devolution of responsibilities to Greater Manchester, and the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, is fundamentally changing the way Salford City Council works in areas of economic development, transport, work and skills, planning, policing and more recently health and social care. 1.3 Salford’s directly elected City Mayor has galvanised the city around eight core priorities – the Great Eight. Delivering against these core priorities will require the sustained commitment and partnership between councillors, partners in the private, public, community and voluntary and social enterprise sectors, and the city’s residents. This is even more the case in the light of ongoing national policy changes, the impending departure of the UK from the EU, and continued austerity in funding for vital local services. The city’s councillors will have an absolutely central role in delivering against these core priorities, working with all our partners and residents to harness the energies and talents of all of the city. -

Ofsted Report December 2014

School report Cheadle Hulme High School Woods Lane, Cheadle Hulme, Cheadle, Cheshire, SK8 7JY Inspection dates 10–11 December 2014 Previous inspection: Not previously inspected as an academy Overall effectiveness This inspection: Outstanding 1 Leadership and management Outstanding 1 Behaviour and safety of pupils Outstanding 1 Quality of teaching Outstanding 1 Achievement of pupils Outstanding 1 Sixth form provision Outstanding 1 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is an outstanding school. Cheadle Hulme High School provides an excellent Students’ behaviour is faultless throughout all year and rounded education for all of its students, groups. They are courteous and respectful to all regardless of their individual backgrounds, staff and mutual respect abounds. preparing them well for their future careers. Procedures to monitor both the quality of learning In Key Stages 3 and 4, students make outstanding and teaching, as well as the progress of individuals, progress in each year group. They leave Year 11 are exacting and exemplary. with standards in GCSE examinations that are well Teachers know their subjects and students above those found nationally. extremely well. Students feed off their teachers’ A higher proportion of most able students achieve expertise, making secure gains in their knowledge GCSE grades A* and A than found nationally. and understanding of any topics being discussed. All groups of students, including those with an Marking is regular and helps students to make the identified special educational need and those from impressive learning gains that result in high a disadvantaged background make the same standards. However, a few teachers have not fully outstanding progress as their peers. -

Revised Redacted Report Lynton Road Lowry Drive 111218 PDF 326 KB

Part 1 - Open to the Public ITEM NO. REPORT OF THE STRATEGIC DIRECTOR PLACE TO LEAD MEMBER FOR PLANNING AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT LEAD MEMBER BRIEFING 11 th December 2018 TITLE: City of Salford (Lynton Road, Lowry Drive and Station Road, Pendlebury) (Prohibition and Restriction of Waiting and Amendment) Order 2018 RECOMMENDATIONS: That the Lead Member for Planning and Sustainable Development consider contents of this report and the deliberations of the Traffic Advisory Panel and make a decision to: 1. Overrule the objections in respect Lynton Road and Station Road. 2. Accede to the objections in part in respect of Lowry Drive. 3. Approve the modified proposals for Lowry Drive at the junction with Station Road set out in this report. 4. Authorise the making of the Traffic Regulation Order in modified form set out in Appendix 6 and 7 hereto. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: A request has been made to the Swinton & Pendlebury Highways Task Group for a relaxation on the waiting restrictions on Lynton Road and new waiting restrictions on Lowry Drive at the junction with Station Road in Salford. A traffic management scheme has been designed to remove some existing double yellow lines and introduce a ‘No Waiting’ Monday to Friday 9 am – 4 pm on Lynton Road. A scheme has also been designed to introduce ‘No Waiting at Any Time’ Traffic Regulation Order on Lowry Drive to cover the extents considered appropriate by the Highways Task Group as indicated on the attached Appendix 1 and 2. Page 1 of 20 The Traffic Regulation Order to introduce ‘No Waiting’ and ‘No Waiting at Any Time’ restrictions was legally advertised on 16 th August 2018 for 21 days, during that time one objection has been received in connection to the proposal for Lynton Road. -

A666 Manchester Road

Part 1 - Open to the Public REPORT OF THE STRATEGIC DIRECTOR PLACE TO THE LEAD MEMBER FOR PLANNING & SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT TRAFFIC ADVISORY PANEL 13th June 2019 TITLE: Salford Bolton Network Improvement Programme (SBNI - DP3) City of Salford (A666 Manchester Road - A666 Bolton Road Area, Salford) (Bus Lane, Prohibition of Waiting, Loading – Unloading Restriction and Mandatory Cycle Lane) (Traffic Regulation Order) 2019 RECOMMENDATIONS: That the Lead Member for Planning & Sustainable Development consider the contents of this report and the deliberations of the Traffic Advisory Panel and makes a decision to approve the amended proposals as detailed in this report. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM) in conjunction with Salford City Council has developed a series of measures across the Salford and Bolton Network Improvement (SBNI) area to make the transport network more efficient. It aims to make travel easier for everyone, including public transport users, pedestrians, cyclists and drivers. Bus passengers in particular will see quicker, more reliable journey times. The improvements will also help encourage economic growth by providing better access to local town centres, employment opportunities, health, education, retail and leisure facilities. Funding for the improvements has been supported by Central Government through the Greater Manchester Local Growth Deal. A scheme within this programme has been identified for the A666 corridor, including Manchester Road, Clifton and Bolton Road, Pendlebury. 1 The scheme seeks to introduce improved bus reliability by the provision of Regional Centre bound bus lanes, improved bus stop provision, improved cycle facilities as well as upgraded pedestrian crossing facilities. As part of this scheme a suite of Traffic Regulation Orders are proposed including the Bus Lanes as well as the complementary waiting and loading restrictions that are required to ensure that the improvements fully realise the anticipated benefits for buses, general traffic as well as cyclists and pedestrians. -

Walter Bluer (1897 – 1938)

Walter Bluer (1897 – 1938) Walter Bluer was born in April 1897 in Pendlebury in Lancashire. His parents were Alfred Bluer (1864 – 1943) and Mary CartwriGht (1868 – 1902). On the 1901 census, at the age of three, he was livinG with his parents at 7 Ramsden Fold, Clifton, Pendlebury. His mother, Mary died in 1902 at the age of 33. On the 1911 Census, Walter aged 14 was already workinG at a local Pendlebury mine as a hand putter, which is ‘a person who pushes wagons’. This was physically challenGinG work. Around the late 1920s the mines around Pendlebury were facinG the same fate as the Black Country mines in the 1880s; they were closinG down. This was not only because the mines were becominG exhausted, but also the Great Depression was beGinninG. Walter was clearly in need of work and made the decision to move to Staveley. He moved from Pendlebury with his cousin, Herbert Bluer, who was also born in 1897. Walter married Lily Hickman on 8 November 1930 in Staveley. A cousin of Lily’s, Nellie Hickman (1903 – 1985), had married John Arnold Bray (1904 – 1938) in 1928. John Arnold Bray was also killed in the Markham Colliery disaster of 1938. Nellie’s older brother was Joseph Henry Hickman (1894 – 1954) who married Eveline Fanny James. She was the widow of Wilfred Haywood (1902 – 1938) who was also killed in the 1938 Markham Colliery disaster. In 1931 Walter and Lily had a dauGhter, Dorothy M Bluer (1931 - ). Walter was killed on the 5 May 1938 at Markham Colliery, alonG with 78 other men. -

Rotala Prestwich

Rotala Prestwich - Eccles 66 via Pendlebury - Swinton - Worsley Monday to Friday Ref.No.: 25E Commencing Date: 26/10/2020 Tender Code T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 T450 Service No 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 Prestwich Tesco -------- -------- 07031 08121 09151 10151 11151 12151 13151 14151 15151 16151 Scholes Ln/Bury Old Rd -------- -------- 07101 08191 09221 10221 11221 12221 13221 14221 15221 16221 Agecroft Dauntesy Ave -------- -------- 07181 08281 09301 10301 11301 12301 13301 14301 15301 16311 Pendlebury Windmill -------- -------- 07271 08371 09391 10391 11391 12391 13391 14391 15391 16411 Mossfield Rd -------- 06281 07301 08401 09421 10421 11421 12421 13421 14421 15421 16441 Swinton Church -------- 06341 07361 08461 09481 10481 11481 12481 13481 14481 15481 16511 Wardley Ash Dr -------- 06401 07421 08521 09541 10541 11541 12541 13541 14541 15541 16571 Worsley Court House 05571 06531 07551 09071 10071 11071 12071 13071 14071 15071 16071 17121 Peel Green Unicorn St 06071 07031 08051 09171 10171 11171 12171 13171 14171 15171 16181 17231 Eccles Interchange 06161 07121 08141 09271 10261 11261 12261 13261 14261 15261 16281 17331 Tender Code T450 T450 T450 T450 Service No 66 66 66 66 Prestwich Tesco 17201 18301 19301 21301 Scholes Ln/Bury Old Rd 17271 18371 19361 21361 Agecroft Dauntesy Ave 17361 18451 19431 21431 Pendlebury Windmill 17461 18541 19511 21511 Mossfield Rd 17491 18571 19541 21541 Swinton Church 17561 19031 19591 21591 Wardley Ash Dr 18021 19091 20041 22041 Worsley Court House 18171 19221 20111 -

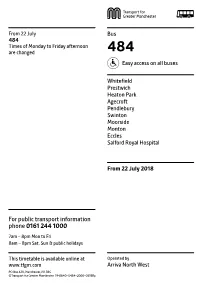

484 Times of Monday to Friday Afternoon Are Changed 484 Easy Access on All Buses

From 22 July Bus 484 Times of Monday to Friday afternoon are changed 484 Easy access on all buses Whitefield Prestwich Heaton Park Agecroft Pendlebury Swinton Moorside Monton Eccles Salford Royal Hospital From 22 July 2018 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Arriva North West PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 19-0640–G484–2000–0519Rp Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Arriva North West large print, Braille or recorded information 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Liverpool, L9 5AE Telephone 0344 800 4411 Easy access on buses Journeys run with low floor buses have no Travelshops steps at the entrance, making getting on Eccles Church Street and off easier. Where shown, low floor Mon to Fri 7.30am to 4pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Saturday 8am to 11.45am and 12.30pm to space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the 3.30pm bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Sunday* Closed easy access services where these services are *Including public holidays scheduled to run. Using this timetable Timetables show the direction of travel, bus numbers and the days of the week. Main stops on the route are listed on the left. Where no time is shown against a particular stop, the bus does not stop there on that journey. -

For Public Transport Information Phone 0161 244 1000

From 11 April Bus 8 Times are changed 8 Easy access on all buses Bolton Moses Gate Farnworth Kearsley Pendlebury Irlams o’ th’ Height Pendleton Manchester From 11 April 2021 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Diamond PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 21-SC-0321–G8–web–0321 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Diamond large print, Braille or recorded information Weston Street phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Bolton BL3 2AW Easy access on buses Telephone 01204 937535 Email [email protected] Journeys run with low floor buses have no www.diamondbuses.com steps at the entrance, making getting on and off easier. Where shown, low floor buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Travelshops space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Bolton Interchange bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Mon to Fri 7am to 5.30pm easy access services where these services are Saturday 8am to 5.30pm scheduled to run. Sunday* Closed Manchester Shudehill Interchange Using this timetable Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm Timetables show the direction of travel, bus Sunday Closed numbers and the days of the week. Public hols 10am to 1.45pm and Main stops on the route are listed on the left. 2.30pm to 5.30pm Where no time is shown against a particular stop, *Including public holidays the bus does not stop there on that journey. -

Bolton Museum

GB 0416 Pattern books Bolton Museum This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 29093 The National Archives List of Textile samples of woven, printed, dyed etc. fabric in the collections of Bolton Museum (Jan. 1977) R.J.B. Description Date Accession no. / 1 Peel Pattern Book - A pattern book of the calico-print circa trade. 36 leaves of notes and pattern samples and 1807-1821 D.1.1971. loosely inserted leaves. Belonged to Robert Peel, fath er of Sir Robert Peel, from print works of Church and Bury. 1 Pattern Book of printed and woven textile designs from 1841-46 D.3.1969. James Hardcastle & Co. ^Bradshaw Works. 1 Pattern Book of printed textile designs from James 1836-44 D. 2.1969 Hardcastle & Co., Bradshaw Works. 9 coloured Patterns on paper of various sizes, illust- A. 3.1967 rating different patterns U3ed in dyeing & printing cotton. 1 Book recording prices and samples referring to dyeing 1824-1827 A. 1.1967 and printing of cotton. Samples of printed and dyed cloth stuck in the book. 1 Book recording instructions and reports on various 1809 A.2.1967 dyeing processes for cotton, using different substances and how to obtain specific colours. Samples of printed and dyed textiles stuck in the book. Book inscribed *John Mellor Jnr. 1809". 1 Sample Book containing 19 small pieces of muslins made 1837 48-29 1/14 by John Bradshaw, Manufacturer, about 1837- John Bradshaw had previously been employed as manager of hand-loom weavers and in 1840 was appointed Relieving Officer for the Western District of Great Bolton. -

Employment Appeal Tribunal Rolls Building, 7 Rolls Buildings, Fetter Lane, London Ec4a 1Nl

Appeal No. UKEAT/0304/19/RN EMPLOYMENT APPEAL TRIBUNAL ROLLS BUILDING, 7 ROLLS BUILDINGS, FETTER LANE, LONDON EC4A 1NL Heard at the Tribunal (conducted remotely) on 25 – 26 February 2021 Judgment handed down on 4 June 2021 Before THE HONOURABLE MRS JUSTICE STACEY MR D BLEIMAN MRS M V McARTHUR BA FCIPD THE CHIEF CONSTABLE OF GREATER MANCHESTER POLICE APPELLANT (1) MR ANDREW ASTON (2) MR JOHN SCHOFIELD (3) MR JOHN BYRNE RESPONDENTS JUDGMENT Copyright 2021 APPEARANCES For the Appellant Mr Simon Gorton QC (One of Her Majesty’s Counsel) Instructed by: Greater Manchester Police Legal Services c/o Openshaw Complex Lawton Street Openshaw Manchester M11 2NS For the Respondents Mr Jack Feeny (Of Counsel) Instructed by: Penningtons Manches Cooper LLP 125 Wood Street London EC2V 7AW UKEAT/0304/19/RN SUMMARY TOPICS: WHISTLEBLOWING, PROTECTED DISCLOSURES, JURISDICTIONAL/TIME POINTS & PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE The Employment Tribunal did not err in its approach to the question of causation in a protected interest disclosure detriment claim and it correctly applied the burden of proof. However the contents of a witness statement made in separate employment tribunal proceedings by one of the police officers about whom protected interest disclosures had been made which criticised the first claimant (the respondent to the appeal) was protected by judicial proceedings immunity (JPI) and could not constitute a detriment. Most regrettably the JPI point had not been raised before the tribunal. Bearing in mind the importance of the JPI doctrine to the integrity of the judicial process, in exercising its discretion in accordance with the guidance in The Secretary of State v Rance [2007] IRLR 665 the appeal tribunal allowed the point to be raised for the first time on appeal. -

Studying Media and Performance at Salford

Studying Media and Performance at Salford Say hello to Rada (pictured) and Elinor, our Student Ambassadors! How many of these questions about famous Salford people can you answer? Q1. Which of these comedians did not attend the University of Salford? John Thomson went to the School of Theatre at Manchester Polytechnic (now Manchester Metropolitan University). Jason Manford and Peter Kay both studied Media and Performance. Luisa Omielan studied Performing Arts (now Theatre and Performance Practice). Q2. Which of these musicians does not hold an honorary degree from the University of Salford? Liam Fray (The Courteeners) Graham Nash (The Hollies, Crosby, Stills and Nash) Peter Maxwell Davies - Composer Peter Hook (Joy Division, New Order) Q2. Which of these musicians does not hold an honorary degree from the University of Salford? Peter Maxwell Davies Master of the Queen’s Music A set menu… Induction Workshops • The first three weeks* of your University career will be spent workshopping a modern classic play. • You will be working as an ensemble with a group of your new fellow-students • Your leader will be an experienced practitioner with an exciting approach to performing the text • *Subject to University/Government advice! The First Year • Trimester One: • Trimester Two: • Acting Methods • Acting for Recorded Media • Production Skills • Production Workshop • Critical and Textual Studies • Performance In Context A typical first-year timetable • Trimester One: • Trimester Two: • Monday – free day • Monday - Performance in Context • Tuesday a.m. - Critical & Textual Studies • Tuesday - Production Workshop • Tuesday p.m. - Acting Methods • Wednesday – free day • Wednesday - Acting Methods • Thursday a.m.- Production Workshop • Thursday - Production Skills • Thursday p.m.- Acting for Recorded Media • Friday - Production Skills • Friday - Acting for Recorded Media Q3. -

FIXTURES 21/22 Officialbwfc | Officialbwfc | Officialbwfc

Bolton Wanderers Football Club BUS SERVICE OFFICIAL FIXTURES 21/22 officialbwfc | OfficialBWFC | officialbwfc www.eticketing.co.uk/bwfc Date Opponents V KO F A Date Opponents V KO F A August January SAT 7 MILTON KEYNES DONS H 15:00 SAT 1 ROTHERHAM UNITED A 15:00 TUE 10 BARNSLEY CARABAO CUP ONE H 20:00 WED 5 CARABAO CUP SEMI-FINAL (1) SAT 14 A.F.C. WIMBLEDON A 15:00 SAT 8 CAMBRIDGE UNITED OR EMIRATES FA CUP 3 H 15:00 TUE 17 LINCOLN CITY A 19:45 WED 12 CARABAO CUP SEMI-FINAL (2) SAT 21 OXFORD UNITED H 15:00 SAT 15 IPSWICH TOWN H 15:00 WED 25 CARABAO CUP TWO SAT 22 SHREWSBURY TOWN A 15:00 SAT 28 CAMBRIDGE UNITED A 15:00 SAT 29 SUNDERLAND** H 15:00 TUE 31 PORT VALE PAPA JOHN’S TROPHY H 19:00 February September SAT 5 MORECAMBE OR EMIRATES FA CUP 4 A 15:00 TUE 8 CHARLTON ATHLETIC H 20:00 SAT 4 BURTON ALBION** H 15:00 SAT 12 OXFORD UNITED A 15:00 SAT 11 IPSWICH TOWN A 15:00 SAT 19 A.F.C. WIMBLEDON H 15:00 SAT 18 ROTHERHAM UNITED H 15:00 TUE 22 LINCOLN CITY H 20:00 WED 22 CARABAO CUP THREE SAT 26 MILTON KEYNES DONS A 15:00 SAT 25 SUNDERLAND A 15:00 SUN 27 CARABAO CUP FINAL TUE 28 CHARLTON ATHLETIC A 19:45 March October WED 2 EMIRATES FA CUP 5 SAT 2 SHREWSBURY TOWN H 15:00 SAT 5 GILLINGHAM A 15:00 TUE 5 LIVERPOOL U21’S PAPA JOHN’S TROPHY H 19:00 SAT 12 PLYMOUTH ARGYLE H 15:00 SAT 9 SHEFFIELD WEDNESDAY** A 15:00 CREWE ALEXANDRA SAT 19 OR EMIRATES FA CUP QUARTER-FINAL A 15:00 SAT 16 WIGAN ATHLETIC H 15:00 SAT 26 PORTSMOUTH** H 15:00 TUE 19 PLYMOUTH ARGYLE A 19:45 April SAT 23 GILLINGHAM H 15:00 SAT 2 WIGAN ATHLETIC A 15:00 WED 27 CARABAO CUP FOUR