Nobody Rushes You Comprehensive Primary Care for Older Patients With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mounties Dance All Night “For the Kids”

The Campanile Mount Saint Joseph Academy Volume LIII, Number 1 february 2016 Mounties dance all night “For the Kids” Mini-THON Committee: l. to r. Caroline Free ’16, Jade Killion ’18, Olivia Bocklet ’17, Caroline Kardish ’17, Emma Diebold ’16, Maddie Ferrero ’16, Hannah Tubman ’16, Emily Pensabene ’17, Grace Gelone ’17, Abby Schwenger ’18, Annie Princivalle ’18, Katie Zimmerman ’16 and Elena Christen ’17 By Meredith Mayes ’17 and Ava the opportunity to lead and or- Rooney and dodge ball, were in- spoke of her own experience with gettable night. Sophomore Jade Self ’17 chestrate one of Mount’s most stant hits, but nothing compared childhood cancer. Killion said, “Mini-THON is a exciting nights. to the excitement on the dance “I think for a lot of people that night I will remember forever. On Friday, Jan. 15, over 250 “Mini-THON has been my fa- floor. When the 2:30 a.m. rave participated it was interesting to Just knowing that every dollar Mount students participated vorite experience at Mount and hour hit, all signs of exhaustion see that what they were doing for we raised helped bring pediat- in the 3rd annual Mini-Thon, has helped me grow not only as a disappeared as the lights went twelve hours was going towards ric cancer researchers one inch a twelve-hour dance marathon leader but also as a person,” said out and glow sticks were illumi- helping people like me and my closer to finding a cure makes my to raise awareness for pediatric Tubman. nated. friends,” said Bocklet. -

N.K. Jemisin in the City We Became, the Award-Winning Science Fiction Writer Keeps Breaking New Ground P

Featuring 407 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 6 | 15 MARCH 2020 REVIEWS N.K. Jemisin In The City We Became, the award-winning science fiction writer keeps breaking new ground p. 14 Also in the issue: Kevin Nguyen, Victoria James, Jessica Kim, and more from the editor’s desk: Great Escapes Through Reading Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # March is the dreariest month. We know that spring is around the cor- Chief Executive Officer ner, but…it can be a long time coming. If you’re fortunate, you might escape MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] to a Florida beach or some other far-flung destination for rejuvenation. For Editor-in-Chief the rest of us, spring break may come in the form of a book that transports TOM BEER [email protected] us elsewhere, indelibly rendered through prose. Here are five titles, new or Vice President of Marketing coming soon, that the travel agent in me would like to recommend. But be SARAH KALINA [email protected] forewarned: There is frequently trouble in paradise. Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU Saint X by Alexis Schaitkin (Celadon Books, Feb. 18): The title refers [email protected] to the fictional Caribbean island where the Thomas family is on a vacation Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK at an evocatively described resort—“the long drive lined with perfectly ver- [email protected] Tom Beer tical palm trees,” “the beach where lounge chairs are arranged in a parab- Children’s Editor VICKY SMITH ola,” the scents of “frangipani and coconut sunscreen and the mild saline of [email protected] equatorial ocean.” Alas, this family vacation does not end well, forever altering the lives of Claire Young Adult Editor LAURA SIMEON Thomas, age 7 at the time, and Clive Richardson, an employee at the resort. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

MYTHS R, 44ORSE 'MYTHOLOGY ANNA

NOS0-430 ERIC REPORT RESUME ED 010 139 1 a.09.0.67 24 QRE VI NYTHS,..*LAI MATURE ORR ICULUM: STUDENT VERS IOU. it I TZH ABER RaR60230', &.14IVERS ITV OF mesa* =MESE CRP -Pi 449-10 RR- 5.11360-v40 ..45 ED itS C E MP'S Os 13 HC..424i60 cop it SEVENTH GRADE, *STUDY -GUIDES, *CURRIE Cdi.UN GUIDES, -*LITERATURE* *NYTHOLOGY. - ENGLISH C URRI GUM. -LITERATURE PROGRAMS EUGENE, OREGON PROJECT ENGL. UN, NB4 GRAMMAR PRESENTED- HERE WM A ,STUDY t-S_VI OE: FOR.STUDENT USE; A .-SEWENTHGRADE L/ TER ATUR E CURRI CULUNT I NTROOUCTOLir XATER/AL los PaesENTE0 ON GREEK MYTHS r, 44ORSE 'MYTHOLOGY ANNA :. AMERICAN INDIAN r prIfiquisfeatsivoir GUEST IONS SUGGESTED A CT I VItIES9 AND Ass REFERENCE soft of PITIliS VritE PRESENTED. AN ACCONIANY-INS *GUIDE WAS PREPARED FOR TEACfrIERS EL) 010 140I e: UN/ .0) rave:t e PT.PARThMIT EnUCI1.11%; ante wet rA.RE Office of Education mils document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organ:zat:on originating it. Points of view or .op':nions stated do not necessarily represent official -Office of Education position or policy. OREGON CURRICULUM,. STUDY CENTER Trri-S"lir" in 11.3 Literature Curriculum I Studait Version The project reported heksinwas supported through the Cooperative Research Program ofthe Office of Education, U, S. Department of Health,Education, and Welfare. 4 4 r 7777*,\C 1,,IYTHS General. Introduction How was the world made? Where did the first people live? Why are we here? To all of these questions people have sought answers for thousands of years. -

Regional in Nature July - August 2010 East Bay Regional Park District Activity Guide Photo: Isa Polt-Jones

Regional in Nature July - August 2010 East Bay Regional Park District Activity Guide www.ebparks.org Photo: Isa Polt-Jones Fascinated toddlers enjoy the Golden State Model Railroad Museum in Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline. See story page 2. Go birding with a Inside: naturalist – see pages 11, 13, Kids Challenge & Trails Challenge • page 5 and 14. Kayaking Opportunities • page 5 Meteor Shower Campout • page 6 Wheat Harvest at Ardenwood Farm • page 7 Wildlife & Nature Photography • page 9 Lake Del Valle Boat Tours • page 12 Plus: Fourth of July Activities Photo: Bill Knowland Bill Photo: Contents Aquatics/Jr. Lifeguards ........ 4 Recreation Programs ...... 5-6 Ardenwood ....................... 6-8 Black Diamond ..................... 8 Botanic Garden .................8-9 Coyote Hills .....................9-10 Crab Cove ......................10-11 Sunol ......................................11 Tilden Nature Area ......11-12 Summer Other Regional Parks ..12-14 Volunteer Programs ..........14 Adventures Registration & Fees ........... 15 Close to Home Visitor Centers/ Swim Areas ..........................15 The East Bay Regional Park District partners with many small business owners and operators to offer exciting outdoor recreation activities that make living in the East Bay a truly unique experience. Summer highlights include horseback riding programs from Western Trail Riding Services at Las Trampas and Sunol, golf courses and lessons at Willow Park Golf Course near Anthony Chabot and Tilden Golf Course at Tilden, boat rentals at Lake Chabot, Lake Del Valle, and Shadow Cliffs, Mudpuppy’s Tub & Scrub dog washing and Sit & Stay Café at Point Isabel, carousel and steam train rides at Tilden, the Golden State Model Railroad Museum at Miller Knox, the new Lake Anza Beach Club café at Tilden, sailboarding at Crown Beach, and old-fashioned fun at Ardenwood with railcar rides and an organic farm. -

Navigating Troubled Waters a History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Navigating Troubled Waters A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Author: James Mackovjak National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve “If people want both to preserve the sea and extract the full benefit from it, they must now moderate their demands and structure them. They must put aside ideas of the sea’s immensity and power, and instead take stewardship of the ocean, with all the privileges and responsibilities that implies.” —The Economist, 1998 Navigating Troubled Waters: Part 1: A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Part 2: Hoonah’s “Million Dollar Fleet” U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Gustavus, Alaska Author: James Mackovjak 2010 Front cover: Duke Rothwell’s Dungeness crab vessel Adeline in Bartlett Cove, ca. 1970 (courtesy Charles V. Yanda) Back cover: Detail, Bartlett Cove waters, ca. 1970 (courtesy Charles V. Yanda) Dedication This book is dedicated to Bob Howe, who was superintendent of Glacier Bay National Monument from 1966 until 1975 and a great friend of the author. Bob’s enthusiasm for Glacier Bay and Alaska were an inspiration to all who had the good fortune to know him. Part 1: A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Table of Contents List of Tables vi Preface vii Foreword ix Author’s Note xi Stylistic Notes and Other Details xii Chapter 1: Early Fishing and Fish Processing in Glacier Bay 1 Physical Setting 1 Native Fishing 1 The Coming of Industrial Fishing: Sockeye Salmon Attract Salters and Cannerymen to Glacier Bay 4 Unnamed Saltery at Bartlett Cove 4 Bartlett Bay Packing Co. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

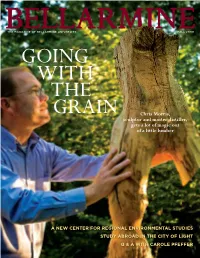

Chris Morris, Sculptor and Master Distiller, Gets a Lot of Magic out of a Little Lumber

Chris Morris, sculptor and master distiller, gets a lot of magic out of a little lumber A new Center for regionAl environmentAl StudieS Study AbroAd in the City of light Q & A with CArole Pfeffer FALL 2009 1 Hundreds of villagers, including tHese cHildren, gatHered in Koniabla village, Mali, earlier tHis year for a spontaneous perforMance of traditional Music, dance and draMa to welcoMe bellarMine druM teacHer yaya diallo, wHo wants to develop a center for west african Musical tradition in His native country. for More, see page 44. Photo by Geoff oliver buGbee 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE Table of Contents 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Can faith and reason coexist? 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 8 WHAT’S ON… The mind of senior Amy Puerto 9 ‘ON THE WAY TO OWENTON’ A poem by Sarah Pennington 10 CONCORD CLASSIC The building boom begins 11 FORE! John Spugnardi laments the end of the Par 3 Course 12 NEWS ON THE HILL 17 LITERACY IN JAMAICA Bellarmine students take another service-learning trip 18 QUESTION & ANSWER Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs Carole Pfeffer 20 WHISKEY AND WOOD Sculptor and master distiller Chris Morris ’80 goes with the grain 26 GROWING A NEW PROGRAM Bellarmine creating a Center for Regional Environmental Studies 30 PARIS IN THE SUMMER We drop in on some study-abroad classes in the City of Light 36 PASSAGE TO INDIA Two Bellarmine staffers reflect on a recent trip to Kerala 44 PHOTOGRAPHER’S NOTEBOOK Geoff Oliver Bugbee shares a haunting night in Mali with Yaya Diallo 48 ALUMNI CORNER 52 CLASS NOTES 54 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: ChRis Morris ’80, works On a sCulpTure for thE aluMni Art ShOw. -

Series 7 LIV.—On a Collection of Bats from Paraguay

This article was downloaded by: [University of Toronto Libraries] On: 02 February 2015, At: 14:28 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Series 7 Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah13 LIV.—On a Collection of Bats from Paraguay Oldfield Thomas Published online: 01 Dec 2009. To cite this article: Oldfield Thomas (1901) LIV.—On a Collection of Bats from Paraguay, Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Series 7, 8:47, 435-443, DOI: 10.1080/03745480109443341 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03745480109443341 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Croi 2021 Program Committee

General Information CONTENTS WELCOME . 2 General Information General Information OVERVIEW . 2 CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION . 3 CONFERENCE SUPPORT . 4 VIRTUAL PLATFORM . 5 ON-DEMAND CONTENT AND WEBCASTS . 5 CONFERENCE SCHEDULE AT A GLANCE . 6 PRECONFERENCE SESSIONS . 9 LIVE PLENARY, ORAL, AND INTERACTIVE SESSIONS, AND ON-DEMAND SYMPOSIA BY DAY . 11 SCIENCE SPOTLIGHTS™ . 47 SCIENCE SPOTLIGHT™ SESSIONS BY CATEGORY . 109 CROI FOUNDATION . 112 IAS–USA . 112 CROI 2021 PROGRAM COMMITTEE . 113 Scientific Program Committee . 113 Community Liaison Subcommittee . 113 Former Members . 113 EXTERNAL REVIEWERS . .114 SCHOLARSHIP AWARDEES . 114 AFFILIATED OR PROXIMATE ACTIVITIES . 114 EMBARGO POLICIES AND SOCIAL MEDIA . 115 CONFERENCE ETIQUETTE . 115 ABSTRACT PROCESS Scientific Categories . 116 Abstract Content . 117 Presenter Responsibilities . 117 Abstract Review Process . 117 Statistics for Abstracts . 117 Abstracts Related to SARS-CoV-2 and Special Study Populations . 117. INDEX OF SPECIAL STUDY POPULATIONS . 118 INDEX OF PRESENTING AUTHORS . .122 . Version 9 .0 | Last Update on March 8, 2021 Printed in the United States of America . © Copyright 2021 CROI Foundation/IAS–USA . All rights reserved . ISBN #978-1-7320053-4-1 vCROI 2021 1 General Information WELCOME TO vCROI 2021 Welcome to vCROI 2021! The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world for all of us in so many ways . Over the past year, we have had to put some of our HIV research on hold, learned to do our research in different ways using different tools, to communicate with each other in virtual formats, and to apply the many lessons in HIV research, care, and community advocacy to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic . Scientists and community stakeholders who have long been engaged in the endeavor to end the epidemic of HIV have pivoted to support and inform the unprecedented progress made in battle against SARS-CoV-2 . -

The Holy See

The Holy See MYSTICI CORPORIS CHRISTI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE MISTICAL BODY OF CHRIST TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN, PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER LOCAL ORDINARIES ENJOYING PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. The doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church,[1] was first taught us by the Redeemer Himself. Illustrating as it does the great and inestimable privilege of our intimate union with so exalted a Head, this doctrine by its sublime dignity invites all those who are drawn by the Holy Spirit to study it, and gives them, in the truths of which it proposes to the mind, a strong incentive to the performance of such good works as are conformable to its teaching. For this reason, We deem it fitting to speak to you on this subject through this Encyclical Letter, developing and explaining above all, those points which concern the Church Militant. To this We are urged not only by the surpassing grandeur of the subject but also by the circumstances of the present time. 2. For We intend to speak of the riches stored up in this Church which Christ purchased with His own Blood, [2] and whose members glory in a thorn-crowned Head. The fact that they thus glory is a striking proof that the greatest joy and exaltation are born only of suffering, and hence that we should rejoice if we partake of the sufferings of Christ, that when His glory shall be revealed we may also be glad with exceeding joy. -

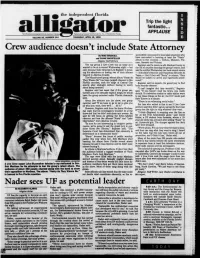

Pubi,.Hed by Cimp,* Comncin 'Nv a G.,,.,V

the independent florida -- a Trip the light fantastic. I wy -- - b w -- APPLAUSE NoI ort caliy associ.d w th th. Unvr1 a rd PubI,.hed by Cimp,* Comncin 'nv a G.,,.,v- . dd VOLUME 53, NUMBER 144 THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 1990 Crew audience doesn't include State Attorney By MIKE BRUSCELL sponsibity was passed to local state attorneys who and DUANE MARSTELLER have succeeded in banning at least the "Nasty" album five Coutlies - Alligator Staff Wnters in DieSt, Manatee. Put- nam, Sarasota and Volusta The rap group 2 live Crew was as nasty as it Register said he wants to add Alachua County to wanted to be at a concert Wednesday night - but the list of counties banning the group's music, and only because State Attorney Len Register is focus- said he notified Wednesday two local record stores ing his attentions on having two of their albums - Schoolkid's Records and Dancetrax Records & banned in Alachua County. Tapes - that if they sell "Nasty" to minors, "they The Miami-based group,whose album "Nasty As would be subject to arrest and vigorously prose- They Wanna Be" has been judged obscene in five cuted " Florida counties, took the stage at Central City Register said he expects the grand jury to find shortly after midnight without having to worry both records obscene about being arrested .I can't imagine that [hey wouldn't," Register Register said last week that if the group per- said. "if you haven't read the lyrics, you really formed any of its sexually explicit songs, he would should.