Answer Brief of Respondent, Ken Pruitt, St. Lucie County Property Appraiser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitol Report November 8, 2006

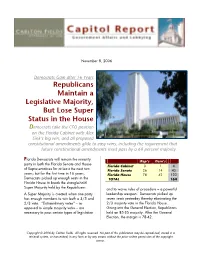

N ovem ber 8, 2006 Dem ocrats Gain after 16 Years Republicans M aintain a Legislative M ajority, But Lose Super Status in the House Dem ocrats take the CFO position on the Florida Cabinet with Alex Sink’s bi win! and all proposed constit"tional am endm ents lide to eas# wins! incl"din the re$"irem ent that f"t"re constit"tional am endm ents m "st pass b# a 6% percent m a&orit#' lorida D em ocrats w ill rem ain the m inority F Rep’s D em ’s party in both the Florida Senate and H ouse Florida Cabinet + # 4 of epresentatives for at least the ne!t tw o Florida Senate 26 #4 40 years" but for the first tim e in #6 years, Florida H ouse 38 42 #20 D em ocrats pic$ed up enou%h seats in the TO TA L 1 6 4 Florida H ouse to brea$ the stran%le&hold Super ' a(ority held by the epublicans) and to w aive rules of procedure 1 a pow erful * Super ' a(ority is created w hen one party leadership w eapon) D em ocrats pic$ed up has enou%h m em bers to w in both a +,- and seven seats yesterday thereby elim inatin% the 2,+ vote) ./!traordinary votes0 1 as 2,+ m a(ority vote in the Florida H ouse) opposed to sim ple m a(ority votes && are 2 oin% into the 2 eneral /lection, epublicans necessary to pass certain types of le%islation held an 8-&+- m a(ority) * fter the 2 eneral /lection, the m ar%in is 38&42) Copyright © 2006 by Carlton Fields. -

Aaron Bean from Fernandina Beach

2020 2022 THE FLORIDA SENATE HANDBOOK 1 2 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT WILTON SIMPSON President of the Senate Welcome to the Florida Senate. During this unprecedented global pandemic, the Senate has partnered with an infectious disease team at Tampa General Hospital and hired an in-house epidemiologist to develop safety protocols designed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and keep Senators and our Senate professional staff as safe as possible. Just like our Senators and staff, you also play an important role in the legislative process. Input from various stakeholders and members of the public is critical, and the Senate is working diligently to ensure Floridians have access to their elected officials as we consider important legislation for our state. Until the COVID-19 vaccine is widely available for those outside of high-risk designation, the Senate is proceeding with care and caution, limiting in-person meetings, and observing social distancing guidelines, mask requirements, and sanitation protocols. For the 2021 Regular Session of the Florida Legislature, the Senate is working in partnership with Florida State University to reserve three remote viewing rooms at the Leon County Civic Center, which provide the opportunity for members of the public to view meetings and virtually address Senate committees in a safe, socially distant manner. We also encourage you to stay involved by viewing all Senate meetings and floor sittings on our website and contacting your local Senator with suggestions, ideas, and feedback. I look forward to the day when we can all be together again walking the halls and chambers where Florida's citizen-legislators have served for generations. -

Inside: Annual Report and Listing of Giving Club Members This Is Truly an Exciting Time for Indian River State College!

Inside: Annual Report and Listing of Giving Club Members This is truly an exciting time for Indian River State College! For the first time in the history of the College, the 2009 Commencement Ceremony included the presentation of Baccalaureate degrees to Indian River State College (IRSC) graduates. These students paved the path for thousands of future students as IRSC expands its four-year programs in coming years. In 2010, IRSC will celebrate its 50th anniversary as the major resource for postsecondary education and career training in St. Lucie, Indian River, Martin, and Okeechobee counties. As the area transitions to become the Research Coast, IRSC commits its superior faculty and outstanding facilities to help students prepare for careers in emerging fields such as biotechnology, photonics, and robotics. Sitting (L to R): Susanne H. Clemons; Michael L. Adams, First Vice Chair; Keeping pace with the College, the IRSC Foundation is actively raising funds to support these Theodore A. Brown II, Second Vice Chair; Alma Lee Loy new programs with faculty, increased library holdings, and scholarships. In 2008-2009, the IRSC Standing (L to R): Dr. Edwin R. Massey, IRSC President; Ann L. Decker, IRSC Foundation provided more than $3.2 million to IRSC for enhanced facilities and instructional Foundation Executive Director; Frank “Sonny” Williamson Jr.; Edwin Arnowitt; Ruth Ann Vega; Dr. John D. Mallonee; Frank M. Irby; John W. Williams; support, and $1.9 million to help hundreds of students through scholarships. Michael D. Minton; José L. Conrado Not pictured: Joseph P. Lembo, Chair; Current funding cuts at the state level make your charitable gifts crucial in our ability to help students, J. -

The Florida House of Representatives

Directory of The Florida House of Representatives Speaker Marco Rubio 420 The Capitol 402 South Monroe Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1300 March 7, 2008 Send all changes to the following e-mail: [email protected] NOTE: This publication was compiled from information received by The Office of the Clerk on or before March 7, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS House Offices .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 House Councils & Committees ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Members .......................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Senate Offices .................................................................................................................................................................. 55 Legislative Support Services ........................................................................................................................................... 56 Other Legislative Offices ................................................................................................................................................. 57 Governor and Lt. Governor ............................................................................................................................................ -

City of Ft. Pierce V. Treasure Coast Marina

DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA FOURTH DISTRICT THE CITY OF FORT PIERCE, FLORIDA, a Florida municipal corporation, FORT PIERCE REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY, a dependent special district of the City of Fort Pierce, KEN PRUITT, the ST. LUCIE COUNTY TAX APPRAISER, and LISA VICKERS, the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, Appellants, v. TREASURE COAST MARINA, LC, a Florida limited liability company, RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT, LC, a Florida limited liability company, and RAINCROSS HOLDINGS, LC, a Florida limited liability company, Appellees. No. 4D14-3064 [April 27, 2016] Appeal from the Circuit Court for the Nineteenth Judicial Circuit, St. Lucie County; William Roby, Judge; L.T. Case No. 562011CA002968. Robert V. Schwerer and James T. Walker of Hayskar, Walker, Schwerer, Dundas & McCain, P.A., Fort Pierce, for appellants The City of Fort Pierce and Fort Pierce Redevelopment Agency. Loren E. Levy and Jon F. Morris of The Levy Law Firm, Tallahassee, for appellant Ken Pruitt, St. Lucie County Property Appraiser. Pamela Jo Bondi, Attorney General, and Robert P. Elson, Assistant Attorney General, Tallahassee, for appellant Department of Revenue. Brigid F. Cech Samole and Jay A. Yagoda of Greenberg Traurig, P.A., Miami, and Jerry Stouck of Greenberg Traurig, LLP, Washington, D.C., for appellees Treasure Coast Marina, LC, Riverfront Developers, LC, and Raincross Holdings, LC. Benjamin K. Phipps of Phipps & Howell, and Harry Morrison, Jr. of Kraig Conn, Tallahassee, for Amicus Curiae Florida League of Cities. WARNER, J. The City of Fort Pierce and Fort Pierce Redevelopment Agency (referred to collectively as “the City”), along with Ken Pruitt, St. -

Journal of the Senate

Journal of the Senate Number 1—Regular Session Tuesday, March 5, 2019 Beginning the Fifty-first Regular Session of the Legislature of Florida convened under the Florida Constitution as revised in 1968, and subsequently amended, and the 121st Regular Session since State- hood in 1845, at the Capitol, in the City of Tallahassee, Florida, on Tuesday, the 5th of March, A.D., 2019, being the day fixed by the Constitution of the State of Florida for convening the Legislature. CONTENTS we turn and ask with all sincerity to help us, as we strive to lead our great State of Florida. Address by Governor . 3 You have endowed us with tremendous abilities to lead and govern, Address by President . 2 but we turn to you as we stand at a new legislative session. Our dis- Call to Order . .1 cerning eyes look diligently to the work before us, but we also know your Committee Substitutes, First Reading . 149 eyes see clearly what must be done in this vast State of Florida. Committees of the Senate . 174 Communication . 175 These collective elected public servants and members of this legis- Executive Business, Appointments . 172 lature stand before you and one another in the hopes that together, Executive Business, Appointments Withdrawn . 168 great things are possible. Their love for this great state shines through Executive Business, Suspensions . 160 their dedication. We ask that you search their hearts and minds. Allow House Messages, Final Action . 175 them to see the dignity of their office and inspire them to greatness. We Introduction and Reference of Bills . -

TOBACCO-RELATED DISEASES: MAKING a DIFFERENCE 2007 Annual Report

TOBACCO-RELATED DISEASES: MAKING A DIFFERENCE 2007 Annual Report February 1, 2008 The Honorable Charlie Crist, Governor The Honorable Ken Pruitt, Senate President The Honorable Marco Rubio, House Speaker Surgeon General Ana M. Viamonte Ros, M.D., M.P.H., Florida Department of Health Dear Governor Crist, President Pruitt, Speaker Rubio, and Surgeon General Viamonte Ros: On behalf of the Biomedical Research Advisory Council, I am pleased to present the 2007 James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program Annual Report. In keeping with section 215.5602, Florida Statutes, this report accounts for the use of $9 million invested by the state during this year and documents the most immediately tangible grantee accomplishments--new publications and additional related research funding. Our report also describes the careful peer review and grants management processes we have put in place to ensure good stewardship of the funds entrusted and provides a briefing on Florida’s most recent share of federal funding for biomedical research. In this year’s report we highlight the scientific accomplishments of our sponsored researchers from the perspective of the tobacco-related behaviors and diseases that are the focus of their work. Making significant advances in preventing, diagnosing, treating, and curing tobacco-related diseases is a long-term undertaking. While it is important to maintain realistic expectations for the pace at which measurable progress can be made, we are proud to feature some outstanding Florida researchers, particularly the rising generation of young investigators, who are producing notable scientific discoveries and promising new treatments for many diseases with this critical funding. These are challenging financial times, and we know you have had to make many hard decisions that call for sacrifices in worthwhile programs. -

2020 Legislative Session Review

2020 FSA Annual Conference Building a Clear Vision in Stormwater Management 2020 Legislative Session Review Kurt Spitzer KSA [email protected] (850) 228-6212 Today’s Agenda 1. General background for 2020 Session 2. Primary legislation of interest to stormwater programs 3. Implementing legislation and other regulatory initiatives 4. Looking to 2021 www.florida-stormwater.org General Background for 2020 Session 1. Florida’s Fiscal Condition 2. Significant interest in water quality 3. Preemption philosophy still growing General Background for 2020 Session 1. Florida’s Fiscal Condition (as of January 2020) ▪ Generally stable, especially when compared to other states ▪ But a long ways off from pre-recession in terms of tax revenues ▪ Tax structure ill-prepared for significant exogenous shock Change in Tax Revenue from State’s Peak Quarter, Adjusted for Inflation Nationwide Florida Fiscal Year Vetoed Total Budget Governor 2003-2004 $21,169,517 $53,502,561,910 Jeb Bush 2004-2005 $349,344,689 $58,036,663,978 Jeb Bush 2005-2006 $179,572,268 $63,076,088,492 Jeb Bush 2006-2007 $447,907,053 $71,326,284,400 Jeb Bush 2007-2008 $459,167,584 $71,953,311,480 Charlie Christ 2008-2009 $251,140,000 $65,024,050,364 Charlie Christ 2009-2010 $6,000,000 $66,536,360,098 Charlie Christ 2010-2011 $171,573,068 $70,377,423,887 Charlie Christ 2011-2012 $615,347,550 $69,676,639,159 Rick Scott 2012-2013 $142,752,177 $70,036,652,091 Rick Scott 2013-2014 $367,950,394 $74,298,188,334 Rick Scott 2014-2015 $68,850,121 $77,081,082,124 Rick Scott 2015-2016 $461,387,164 $78,697,999,841 Rick Scott 2016-2017 $256,144,027 $82,348,890,492 Rick Scott 2017-2018 $11,900,000,000 $82,418,458,905 Rick Scott 2018-2019 $64,050,000 $88,700,000,000 Rick Scott 2019-2020 $131,281,341 $91,106,375,235 Ron DeSantis 2020-2021 $1,000,337,940 $93,200,000,000 Ron DeSantis Year Governor President Speaker Gen. -

Document 4015 in Box 1 of Job 13390 Scanned on 10/18/2013 9:15 PM by Docufree Corporation Jlj"

Document 4015 in Box 1 of Job 13390 Scanned on 10/18/2013 9:15 PM by Docufree Corporation jlj" ! ljjljllj l J.M. "Buddy" Phillips, Executive Director Florida Sheri ffs Association Please allow me to introduce you to a special edition of The I hope you' ll join me in Sheriffs Star magazine, our Annual Guide to Government. welcoming those Sheriffs. You Each year, we research and compile important informa- can read more about them in the Sherdfs' biographies begin- tion for use by state agencies, legislators, local o5cials and ning on page 31, And be sure to catch our story about the anyone else needing a road map of public o5cials and gov- New Sheriffs School on page 52. ernment o5ces. That's what you' ll find in the front of this Which brings me to another thought. In the past, some magazine. people have proposed term limits for local o5cials. What I'd In the last 12 pages, we' ve included updates on criminal like to point out is the fact that there seems to be a natural justice issues that you' ll be hearing about in the 1997 Leg- "term limit" built into the system —the views of the voters. islative session. You can also read what two of your legisla- In the past nine years I've been associated with the Flori- tors have to say about what will take place in the halls of the da Sheriffs Association, we' ve had 66 new Sheriffs in the state Capitol. of Florida. Some counties have experienced more turnover Expect your Florida Sheriffs to be out there in full force than others, but still it's a large number considering there are during the session, as always, getting across vital information only 67 counties. -

A Productive Talk

BEN EXPERIENCE A FRESH START VOTE AUG 18th LOVEL Hardworking Honest FOR Accountable WĂŝĚƉŽůŝƟĐĂůĂĚǀĞƌƟƐĞŵĞŶƚƉĂŝĚĨŽƌĂŶĚĂƉƉƌŽǀĞĚ Property Appraiser ďLJĞŶ>ŽǀĞů͕ZĞƉƵďůŝĐĂŶ͕ĨŽƌWƌŽƉĞƌƚLJƉƉƌĂŝƐĞƌ 20202020ElectionElection County Commission District 3 candidates answer questions Starts on Page 9 Another online candidate forum is held Page 12 $1 Published Weekly, Read Daily Our 122nd Year, 31st Issue One Section Serving Wakulla County For 122 Years Thursday, July 30, 2020 SCHOOLS School opening moves forward But school board gives superintendent authority to delay Aug. 13 opening if necessary By WILLIAM SNOWDEN district’s $60 million to provide more time to Editor budget. prepare and see how oth- Open Houses set Several school board er schools that opened The district released a sched- Moving forward with members and the presi- early fared. reopening schools on dent of the local teachers School Board Chair ule for school Open Houses last Aug. 13, the Wakulla union expressed concern Greg Thomas offered a week. Because of Covid pre- County School Board about safely reopening different perspective, cautions, the Open Houses are voted Monday to give Su- schools. noting that “Pay doesn’t geared to students transitioning perintendent of Schools Superintendent Pearce start til school starts.” to new schools, such as Pre-K, Bobby Pearce the author- reiterated his projection Moving the start date to Kindergarteners, 6th graders at ity to delay the opening of that 90% of students September would mean the middle schools, 9th graders schools without a special will return to physical no pay for teachers in at the high school, as well as meeting. classrooms when school School Superintendent August. The school board opens. -

Overview of the 2016 Legislative Session

Overview of the 2016 Legislative Session May 22, 2016 10:30 AM EST – 11:30 AM EST www.florida‐stormwater.org Upcoming Events! Stormwater Operator Certification Classes http://www.florida‐stormwater.org/training‐center Stormwater Operator Re‐Certification Webinars June 1, 2016 Level 1 Operator: 9am – 11am Level 2 Operator: 2pm –4pm Annual Conference and Exhibits June 15‐17, 2016 Sanibel Harbour Marriott, Ft. Myers Engineers | Scientists | Advocates Peter Owens, PE, ME –Senior Environmental Engineer • 35 years experience • Previously Hillsborough County EPC • Managed the Wetlands Engineering Section specializing in wetlands permitting, hydrology and agency permit delegation implementation, specifically with ACOE, FDEP, and the Tampa Port Authority [email protected] Robert Wronski, PE, MS –Project Manager • 25 years experience • Previously Pasco County Stormwater • Supervised In‐House Design Team and Design Consultants • Stormwater Design and Construction Plans expertise [email protected] Meet the Presenters Kurt Spitzer Kelli Hammer Levy www.florida‐stormwater.org Today’s Overview • General Background for 2016 Session • Primary Water Quality Legislation • Upcoming Regulatory Issues www.florida‐stormwater.org General Background for 2016 Session 1. Florida’s Fiscal Condition continues to Improve 2. Less interest in “Regulatory Streamlining” ‐‐‐ but also less hesitation to pre‐empt locals 3. Continued interest in water quality/supply 4. Improved House‐Senate Relations Year Governor President Speaker Bills Filed Bills Passed % Passed -

October 1,2007 the Honorable Ken Pruitt President, the Florida Senate Capitol, Room 409 C 402 S. Monroe Street Tallahassee, Flor

Southwest Florida 2379 Broad Street, Brooksville, Florida 346046899 (352) 796-7211 or 1-800-423-1476(FL only) Ct SUNCOM 6284150 TDD only 1-800-2316103 (FL only) On the Internet at: WaterMatters.org ~n Equal Bartow Servlce Office Lecanto Service Office Sarasota Servlce Offlce Tampa Sewlce Offlce Opportunity Employer 170 Century Boulevard Suite 226 6750 Fruitville Road 7601 Highway 301 North Bartow, Florida 3383B7700 3600 West Sovereign Path Sarasota, Florida 34240.9711 Tampa, Florida 33637-6759 (863) 534-1448 or Lecanto, Florida 344618070 (941) 377-3722 or (813) 9857481 or 1-800492-7862 (FL only) (352) 527-8131 1-800.320.3503 (FL only) 1800-8360797 (FL only) SUNCOM 572-6200 SUNCOM 531-6900 SUNCOM 5782070 Judlth C. Whitehead October 1,2007 Chair, Hernando Neil Cornbee Vice Chair, Polk Todd Pressman Secretary, Pinellas The Honorable Ken Pruitt Jennlfer E. Clourhey President, The Florida Senate Treasurer, Hillsborough Capitol, Room 409 C Thomas G. Dabney Sarasota 402 S. Monroe Street Patrltla M. GI- Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1 100 Manatee Heidi B. McCree Hillsborough The Honorable Marco Rubio Ronald E. Oakley Speaker, The Florida House of Representatives Pasco Capitol, Room 420 C Sallle Parks Pinellas 402 S. Monroe Street Marltza RovlrbForlno Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1300 Hillsborough Patsy C. Symons I The Honorable Michael S. "Mike" Bennett, Alternating Chair The Honorable Greg Evers, Alternating Chair Joint Administrative Procedures Committee Davld L. Moore Room 120, Holland Building Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1 300 Wllllam S. Bllenky General Counsel Dear Sirs: Enclosed is the Biennial Report by the Southwest Florida Water Management District required by Section 120.74, Florida Statutes, which certifies that the District has complied with the requirements of this section.