The Province of Sofala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozambique, [email protected]

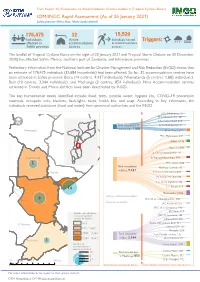

Flash Report 15 | Evacuations to Accommodation Centres Update 2 (Tropical Cyclone Eloise) IOM/INGC Rapid Assessment (As of 25 January 2021) Sofala province (Beira, Buzi, Nhamatanda district) 176,475 32 15,520 Individuals Active Individuals hosted Triggers: in accommodations aected in accommodation Sofala province centres centres The landfall of Tropical Cyclone Eloise on the night of 23 January 2021 and Tropical Storm Chalane on 30 December 2020) has aected Sofala, Manica, southern part of Zambezia, and Inhambane provinces. Preliminary information from the National Institute for Disaster Management and Risk Reduction (INGD) shows that an estimate of 176,475 individuals (35,684 households) had been aected. So far, 32 accommodation centres have been activated in Sofala province: Beira (14 centres, 9,437 individuals), Nhamatanda (5 centres, 1,885 individuals), Buzi (10 centres, 3,344 individuals), and Machanga (3 centres, 854 individuals). Nine Accommodation centres activated in Dondo and Muasa districts have been deactivated by INGD. The top humanitarian needs identied include: food, tents, potable water, hygiene kits, COVID-19 prevention materials, mosquito nets, blankets, ash-lights, tarps, health kits, and soap. According to key informants, the individuals received assistance (food and water) from provincial authorities and the INGD. EPC- Nhampoca: 27 Maringue EPC Nhamphama: 107 EPC Felipe Nyusi: 418 Total evacuations in EPC Nhatiquiriqui: 74 Cheringoma Nhamatanda: Gorongosa 1,885 ES de Tica: 1,259 EPC- Matadouro: 493 IFAPA: 1,138 Muavi 1: 1,011 Muanza E. Comunitaria SEMO: 170 Nhamatanda E. Especial Macurungo: 990 5 EPC- Chota: 600 Total evacuations Munhava Central: 315 in Beira: 9,437 Dondo E S Sansao Mutemba: 428 ES Samora Machel: 814 E. -

Manica Tambara Sofala Marromeu Mutarara Manica Cheringoma Sofala Ndoro Chemba Maringue

MOZAMBIQUE: TROPICAL CYCLONE IDAI AND FLOODS MULTI-SECTORAL LOCATION ASSESSMENT - ROUND 14 Data collection period 22 - 25 July 2020 73 sites* 19,628 households 94,220 individuals 17,005 by Cyclone Idai 82,151 by Cyclone Idai 2,623 by floods 12,069 by floods From 22 to 25 July 2020, in close coordination with Mozambique’s National Institute for Disaster Management (INGC), IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) teams conducted multi-sectoral location assessments (MSLA) in resettlement sites in the four provinces affected by Cyclone Idai (March 2019) and the floods (between December 2019 and February 2020). The DTM teams interviewed key informants capturing population estimates, mobility patterns, and multi-sectoral needs and vulnerabilities. Chemba Tete Nkganzo Matundo - unidade Chimbonde Niassa Mutarara Morrumbala Tchetcha 2 Magagade Marara Moatize Cidade de Tete Tchetcha 1 Nhacuecha Tete Tete Changara Mopeia Zambezia Sofala Caia Doa Maringue Guro Panducani Manica Tambara Sofala Marromeu Mutarara Manica Cheringoma Sofala Ndoro Chemba Maringue Gorongosa Gorongosa Mocubela Metuchira Mocuba Landinho Muanza Mussaia Ndedja_1 Sofala Maganja da Costa Nhamatanda Savane Zambezia Brigodo Inhambane Gogodane Mucoa Ronda Digudiua Parreirão Gaza Mutua Namitangurini Namacurra Munguissa 7 Abril - Cura Dondo Nicoadala Mandruzi Maputo Buzi Cidade da Beira Mopeia Maquival Maputo City Grudja (4 de Outubro/Nhabziconja) Macarate Maxiquiri alto/Maxiquiri 1 Sussundenga Maxiquiri 2 Chicuaxa Buzi Mussocosa Geromi Sofala Chibabava Maximedje Muconja Inhajou 2019 -

World Bank Documents

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 84667-MZ Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT THE REPUBLIC OF MOZAMBIQUE DECENTRALIZED PLANNING AND FINANCE PROJECT (IDA-HO670-MOZ) February 18, 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized IEG Public Sector Evaluation Independent Evaluation Group Public Disclosure Authorized ii Currency Equivalents (annual averages) Currency Unit = Mozambican metical (MZM) 2004 US$1.00 MZN 22,144.71 2005 US$1.00 MZN 22,850.81 2006 US$1.00 MZN 25,758.32 (January to July) 2006 US$1.00 MZN 25.89 (July to December) 2007 US$1.00 MZN 25.79 2008 US$1.00 MZN 24.19 2009 US$1.00 MZN 27.58 2010 US$1.00 MZN 34.24 Abbreviations and Acronyms CCAGG Concerned Citizens of Abra for Good Government CPIA Country Program and Institutional Assessments DGA Development Grant Agreement DPFP Decentralized Planning and Finance Project FCA Fundo de Compensação Autárquica FIL Fundo de Iniciativa Local FRELIMO Frente de Libertação de Moçambique GTZ German Technical Cooperation ICR Implementation Completion Report IDA International Development Association IEG Independent Evaluation Group IEGPS IEG Public Sector Evaluation M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MOPH Ministry of Public Works and Housing MOZ Mozambique NDPFP National Decentralized Planning and Finance Project PAD Project Appraisal document PARPA Action Plan for Reduction of Absolute Poverty PEDD Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento Distrital PEFA Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability PESOD Plano Económico Social e Orçamento Distrital PPAR Project Performance Assessment Report PRSCs Poverty Reduction Strategy Credits PSRP Public Sector Reform Project UNCDF United Nations Capital Development Fund UNDP United Nations Development Program UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund Fiscal Year Government: January I - December 31 Acting Director-General, Independent Evaluation Mr. -

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

The Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo) As Described by Ex-Patticipants

The Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo) as Described by Ex-patticipants Research Report Submitted to: Ford Foundation and Swedish International Development Agency William Minter, Ph.D. Visiting Researcher African Studies Program Georgetown University Washington, DC March, 1989 Copyright Q 1989 by William Minter Permission to reprint, excerpt or translate this report will be granted provided that credit is given rind a copy sent to the author. For more information contact: William Minter 1839 Newton St. NW Washington, DC 20010 U.S.A. INTRODUCTION the top levels of the ruling Frelirno Party, local party and government officials helped locate amnestied ex-participants For over a decade the Mozambican National Resistance and gave access to prisoners. Selection was on the basis of the (Renamo, or MNR) has been the principal agent of a desuuctive criteria the author presented: those who had spent more time as war against independent Mozambique. The origin of the group Renamo soldiers. including commanders, people with some as a creation of the Rhodesian government in the mid-1970s is education if possible, adults rather than children. In a number of well-documented, as is the transfer of sponsorship to the South cases, the author asked for specific individuals by name, previ- African government after white Rhodesia gave way to inde- ously identified from the Mozambican press or other sources. In pendent Zimbabwe in 1980. no case were any of these refused, although a couple were not The results of the war have attracted increasing attention geographically accessible. from the international community in recent years. In April 1988 Each interview was carried out individually, out of hearing the report written by consultant Robert Gersony for the U. -

8 the Portuguese Second Fleet Under the Command of Álvares Cabral Crosses the Atlantic and Reaches India (1500-1501)

Amerigo Vespucci: The Historical Context of His Explorations and Scientific Contribution Pietro Omodeo 8 The Portuguese Second Fleet Under the Command of Álvares Cabral Crosses the Atlantic and Reaches India (1500-1501) Summary 8.1 On the Way to India the Portuguese Second Fleet Stops Over in Porto Seguro. – 8.2 Cabral’s Fleet Reaches India. 8.1 On the Way to India the Portuguese Second Fleet Stops Over in Porto Seguro In Portugal, King Manuel, having evaluated the successes achieved and er- rors made during the voyage of the First Fleet (or First Armada), quickly organised the voyage of the Second Fleet to the East Indies. On March 9, 1500, this fleet of thirteen ships, i.e. four caravels and nine larger vessels, carrying a total of 1,400 men (sailors, soldiers and merchants), set sail from Lisbon. Two ships were chartered, one from the Florentines Bartolomeo Marchionni and Girolamo Sernigi, the other from Diogo da Silva, Count of Portalegre. The 240-ton flagshipEl Rey and ten other ships were equipped with heavy artillery and belonged to the Crown. The fleet was under the command of the young nobleman Pedro Álvar- es Cabral (1467-1520) and its mission was to reach the markets of the In- dian Ocean. For this reason, no expense had been spared in equipping the ships; in addition to the artillery they carried a large amount of money and goods for exchange (mainly metals: lead, copper and mercury), and many glittering gifts to be distributed, created by refined artisans. King Manuel remembered Vasco da Gama’s humiliation over the small size of his ships and gifts, and intended to present himself on the eastern markets as a great king whose magnificence could rival that of the Indian princes. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Projectos De Energias Renováveis Recursos Hídrico E Solar

FUNDO DE ENERGIA Energia para todos para Energia CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFÓLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES Edition nd 2 2ª Edição July 2019 Julho de 2019 DO POVO DOS ESTADOS UNIDOS NM ISO 9001:2008 FUNDO DE ENERGIA CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFOLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES FICHA TÉCNICA COLOPHON Título Title Carteira de Projectos de Energias Renováveis - Recurso Renewable Energy Projects Portfolio - Hydro and Solar Hídrico e Solar Resources Redação Drafting Divisão de Estudos e Planificação Studies and Planning Division Coordenação Coordination Edson Uamusse Edson Uamusse Revisão Revision Filipe Mondlane Filipe Mondlane Impressão Printing Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Tiragem Print run 300 Exemplares 300 Copies Propriedade Property FUNAE – Fundo de Energia FUNAE – Energy Fund Publicação Publication 2ª Edição 2nd Edition Julho de 2019 July 2019 CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE RENEWABLE ENERGY ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS PROJECTS PORTFOLIO RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES PREFÁCIO PREFACE O acesso universal a energia em 2030 será uma realidade no País, Universal access to energy by 2030 will be reality in this country, mercê do “Programa Nacional de Energia para Todos” lançado por thanks to the “National Energy for All Program” launched by Sua Excia Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, Presidente da República de Moçam- His Excellency Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, President of the -

Manica Province

Back to National Overview OVERVIEW FOR MANICA PROVINCE Tanzania Zaire Comoros Malawi Cabo Del g ad o Niassa Zambia Nampul a Tet e Manica Zambezi a Manica Zimbabwe So f al a Madagascar Botswana Gaza Inhambane South Africa Maput o N Swaziland 200 0 200 400 Kilometers Overview for Manica Province 2 The term “village” as used herein has the same meaning as “the term “community” used elsewhere. Schematic of process. MANICA PROVINCE 678 Total Villages C P EXPERT OPINION o m l COLLECTION a n p n o i n n e g TARGET SAMPLE n t 136 Villages VISITED INACCESSIBLE 121 Villages 21 Villages LANDMINE- UNAFFECTED BY AFFECTED NO INTERVIEW LANDMINES 60 Villages 3 Villages 58 Villages 110 Suspected Mined Areas DATA ENTERED INTO D a IMSMA DATABASE t a E C n o t r m y p a MINE IMPACT SCORE (SAC/UNMAS) o n n d e A n t n a HIGH IMPACT MODERATE LOW IMPACT l y 2 Villages IMPACT 45 Villages s i s 13 Villages FIGURE 1. The Mozambique Landmine Impact Survey (MLIS) visited 9 of 10 Districts in Manica. Cidade de Chimoio was not visited, as it is considered by Mozambican authorities not to be landmine-affected. Of the 121 villages visited, 60 identified themselves as landmine-affected, reporting 110 Suspected Mined Areas (SMAs). Twenty-one villages were inaccessible, and three villages could not be found or were unknown to local people. Figure 1 provides an overview of the survey process: village selection; data collection; and data-entry into the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) database, out of which is generated the Mine Impact Score (Appendix I). -

Appendix a – the Emergence of Multiparty Systems with Broad Suffrage

VU Research Portal Politics, history and conceptions of democracy in Barue District, Mozambique van Dokkum, A. 2015 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) van Dokkum, A. (2015). Politics, history and conceptions of democracy in Barue District, Mozambique. VU University Amsterdam. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 APPENDIX A – THE EMERGENCE OF MULTIPARTY SYSTEMS WITH BROAD SUFFRAGE Huntington’s (1991) much-discussed theory of “democracy” as being adopted in “waves” during the 19 th and 20 th centuries entails that there have been rather circumscribed periods within these centuries with many transitions from “non-democracy” to “democracy” and few vice versa (1991: 15). Doorenspleet (2005) has re-examined Huntington’s arguments and data. -

Mozambique: Floods

Mozambique: Floods Heavy rains continue to fall across much of the Zambezi River Basin, which has led to increased water levels along the Zambezi and its major tributaries. The government of Mozambique reports that 61,000 people have been displaced and 29 killed. Created by ReliefWeb on 12 February 2007 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs - OCHA Situation Report No. 2, issued 09 Feb 2007 United Nations GMT +2 SITUATION KENYA DR CONGO • Zambezi river and its tributaries still rising; pockets in UNITED REPUBLIC North flooded OF TANZANIA • Despite deteriorating situation, Government of ANGOLA MALAWI ZAMBIA Mozambique (GoM) has yet to declare formal natural ZIMBABWE emergency BOTSWANA Zumbo district • National Institute for Disaster Management (INGC) MOZAMBIQUE MADAGASCAR - completely cut off by road NAMIBIA Maputo Malawi - 15,600 affected estimates that flooding may affect 285,000 people SWAZILAND SOUTH - 60 houses washed away • GoM reports 4,677 houses, 111 schools, 4 health centres AFRICA Mozambique LESOTHO - reports of high levels of Lilongwe diarrhea and malaria and 15,000 hectares of crops destroyed - boats urgrently needed • military has been requested to help with forced Mutarara district for rescue and assistance - completely cut off by road evacuations of 2,500 people TETE Zambia - 6,448 relocated in 8 ACTION Zumbo Cahora Bassa accommodation centres Zumbo Dam Songo Chiuta - WFP has pre-positioned • UN agencies preparing to support GoM in their response 171 MT of food • GoM and WFP organizing preliminary assessment Magoe Cahora Tete • Special Operation for air and water operations being Chire River ZAMBEZIA Bassa Moatize finalized by WFP Rome Changara Zambeze River Mutarara • Mozambique UNCT agreed to prepare CERF proposal to Guro Morrumbala meet emergency response needs Tambara Chemba Zimbabwe Sena Mutarara LINKS MANICA • OCHA Situation Report No. -

IFPP - Integrated Family Planning Program

IFPP - Integrated Family Planning Program Agreement No. #AID-656-A-16-00005 Yearly Report: Oct 2017 to September 2018 - 2nd Year of the Project 0 Table of Contents Acronym list .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Project Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Summary of the reporting period (October 2017 to September 2018) ....................................................... 7 IR 1: Increased access to a wide range of modern contraceptive methods and quality FP/RH services 11 Sub- IR 1.1: Increased access to modern contraceptive methods and quality, facility-based FP/RH services ................................................................................................................................................ 11 Sub- IR 1.2: Increased access to modern contraceptive methods and quality, community-based FP/RH services .................................................................................................................................... 23 Sub-IR 1.3: Improved and increased active and completed referrals between community and facility for FP/RH services .................................................................................................................. 28 IR 2: Increased demand for modern contraceptive methods and quality FP/RH services ..................... 29 Sub IR2.1: Improved