Beyond the Islamic State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Notes August 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY AUGUST 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 109 A Strategy to Contain Hezbollah Ideas and Recommendations Hanin Ghaddar ebanon is not collapsing because it lacks a government or because enacting reforms is too difficult. Rather, it is collapsing because its political L and financial elites refuse to undertake the decision to implement reforms. Instead, they want the next government to look exactly like its predecessors so that it can guarantee the status quo and preserve the corruption at the heart of the country’s politics. Since shortly after the devastating explosion at Beirut’s port in August 2020, an interim government has ruled Lebanon, and the Image: Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan country’s entrenched actors have failed to make the compromises necessary to Nasrallah addresses a crowd allow the deep political-economic reforms that could facilitate a pathway out of by video to mark the Ashura the national crisis. The worsening economic situation has produced alarming festival, August 19, 2021. rates of child hunger, falling wages paired with unaffordable prices for basic REUTERS goods, and rising desperation across the Lebanese demographic spectrum.1 HANIN GHADDAR A STRATEGY TO CONTAIN HEZBOLLAH Operationally, the road map for resolving Lebanon’s followers loyal to sectarian leaders works perfectly crisis is clear. It has been laid out with great specificity well for Hezbollah, allowing the group to both claim by numerous international conferences, defined as total control of the Shia community and to form requirements for aid packages, and integrated into alliances with other Lebanese sects and groups. strategies by international and local actors alike. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................... -

Lebanese Parliamentary Elections 2009: Candidates by Electoral Lists

International Foundation for Electoral Systems Lebanese Parliamentary Elections 2009: Candidates by Electoral Lists 20 May 2009 District Total Number March 14 March 8 Non- Total Seats of Registered Affiliated List Affiliated List Affiliated List per District Candidates Announced Announced Announced Akkar 40 ! ! 7 Minieh-Dinnieh 35 ! 3 Bcharré 8 ! ! 2 Tripoli 40 ! 8 Zgharta 10 ! ! 3 Koura 15 ! ! 3 Batroun 9 ! ! 2 Jbeil 25 ! ! ! 3 Kesrwan 27 ! ! 5 Metn 26 ! ! 8 Baabda 36 ! ! ! 6 Aley 14 ! ! 5 Chouf 21 ! ! 8 Baalbek-Hermel 41 ! 10 Zahlé 61 ! 7 West Bekka-Rashaya 25 ! ! 6 Beirut One 20 ! ! 5 Beirut Two 8 ! ! 4 Beirut Three 41 ! ! 10 Saïda 6 ! 2 Jezzine 22 ! ! 3 Zahrany 10 ! 3 Nabatieh 14 ! 3 Hasbaya-Marjayoun 16 ! 5 Tyre 8 ! 4 Bint Jbeil 9 ! 3 Totals 587 128 Unofficial translation of names by IFES based on data published by the Ministry of the Interior. Electoral lists are identified as bloc-affiliated only after an official announcement, either by the bloc or by affiliated parties. Information accurate as of 19 May 2009. Lebanese Parliamentary Elections 2009 Candidates by Electoral List Akkar 7 seats 3 Sunnite, 2 Greek Orthodox, 1 Alawite, 1 Maronite March 14 affiliated list March 8 affiliated list Khaled Zahraman (FM) SU Mohammad Yehia SU Khaled Daher SU Saoud Al-Youssef SU Mouin Al-Merhebi (FM) SU Wajih Al-Baarini SU Nidal Tohmeh GO Joseph Shahda (FPM) GO Riad Rahal (FM) GO Karim Al-Rassi (Marada) GO Khodor Habib AL Moustapha Hussein AL Hadi Hobeish(FM) MA Mikhaël Daher MA Candidates with no announced list Abdallah Zakaria SU Maher Abdallah -

The Rhosus: Arrival in Beirut

HUMAN RIGHTS “They Killed Us from the Inside” An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Blast WATCH “They Killed Us from the Inside” An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Blast Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-931-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-931-5 “They Killed Us from the Inside” An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Blast Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 9 Port of Beirut: A Case Study in Lebanese Authorities’ Mismanagement and Corruption ...... 11 The Rhosus: -

The Political Affiliation of Lebanese Parliamentarians and the Composition of the Different Parliamentary Blocs IFES Lebanon

Lebanon’s 2009 Parliamentary Elections The political affiliation of Lebanese Parliamentarians and the composition of the different parliamentary blocs International Foundation for Electoral Systems IFES Lebanon Briefing Paper September 2009 Lebanon’s 2009 Parliamentary Elections have resulted in a majority of 71 deputies and an opposition of 57 deputies. Each coalition is composed of different political parties and independent deputies. However, on the 31 st of August, and after the recent position of MP Walid Jumblatt, the Majority forces held a meeting at the residence of designate PM Saad Hariri. While 67 deputies attended the meeting and 2 deputies were outside of Lebanon, MP Najib Mikati and MP Ahmad Karami were not present and declared themselves as “centrists”. The table (1) provides the number of Parliamentarians belonging to each political party and the number of independent Parliamentarians. The table (2) gives the number of deputies in each parliamentary bloc as they stand now. The table (3) provides the political affiliation and the parliamentary bloc of each deputy, indicating that some deputies are members of more than one parliamentary bloc, but within the same coalition of the majority or the opposition. These data are subject to change based on the future political developments. Table (1) Number of Table (2) Number of Political Affiliation deputies Parliamentary Blocs deputies FM 25 Lebanon First 41 Independent/March 14 th 20 Futur Bloc 33 LF 8 Democratic Gathering 11 Kataeb 5 LF 8 PSP 5 Zahle in the Heart 7 Hanchak 2 -

The Lebanese Ministries by Virtue of Law

issue number 166 | January 2017 www.monthlymagazine.com Published by Information International POST-TAËFPOST-TAËF LEBANESELEBANESE GOVERNMENTSGOVERNMENTS “SOVEREIGN MINISTRIES” EXCLUSIVE FOR ZU'AMA AND SECTS Index 166 | January 2017 5 Leader Post-Taëf Lebanese Governments “Sovereign Ministries” 5 Exclusive for Zu'ama and Sects Public Sector “Sovereign Ministries”: 40 Fiefdoms for the Zu'ama of Major Sects Government Refuses to Hold the Constitutionally 47 Binding Parliamentary By-elections 40 Discover Lebanon 50 Ghouma’s impact has reached USA Lebanon Families 51 Al-Hussan families: Lebanese Christian Families 47 3 Editorial Powerful Zu’ama in a Powerless State By Jawad Nadim Adra Since its independence in 1943, Lebanon continues to face successive crises varying in sever- ity depending on the triggers, the stakes and the regional and international contexts. These crises range from the appointment of civil servants, to parliamentary elections, to squab- bling over ministerial portfolios, to governmental and presidential vacancies, to extension or appointment of parliaments as well as to bloody battles that unfolded either intermittently across different regions and periods of time or incessantly as was the case during Lebanon’s 15-year Civil War. All this has translated into a squandering of public funds, wastage of resources, brain-drain, pollution, unemployment, accumulated public debt, growing disparity between the rich and the poor and an absolute collapse in healthcare, education and all other public services. Ap- parently, the sectarian Zu’ama and we, the people, have failed or rather intentionally opted not to build a state. Talking about a fair and equitable electoral law is in fact nothing but empty rhetoric. -

Hezbollah, a Historical Materialist Analysis

Daher, Joseph (2015) Hezbollah : a historical materialist analysis. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/23667 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Hezbollah, a Historical Materialist Analysis Joseph Daher Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of Development SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work, which I present for examination. Signed: ________________________ Date: _________________ 2 Abstract This research aims at giving a comprehensive overview and understanding of the Lebanese party Hezbollah. -

Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon

Social Classes This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Middle East Office. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the opinion of the Foundation. and Political Power in Lebanon Fawwaz Traboulsi Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon Fawwaz Traboulsi This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Middle East Office. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the opinion of the Foundation. Content 1- Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2- From Liberalism to Neoliberalism .................................................................................................................................... 23 3- The Oligarchy ................................................................................................................................................................................. 30 4- The Middle Classes............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 44 5- The Working Classes ................................................................................................................................................................. -

2015 - 2016 Model Arab League

2015 - 2016 Model Arab League BACKGROUND GUIDE Joint Cabinet Crisis – March 14 vs. March 8 Alliance ncusar.org/modelarableague Original draft by Ramin Sina, Co-Coordinator of the Joint Cabinet Crisis at the 2015 Summer Intern Model Arab League, with contributions from the dedicated staff and volunteers at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations 1989 TA’IF ACCORD - Power-Sharing Agreement The Ta’if Agreement—a consociational or power-sharing agreement enacted by the Lebanese government in 1989—constitutes a reconstruction of the electoral system, evening out the seats for Christians and Muslims of the country, as well as among Shiites and Sunnis. The agreement came about with the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 1989: “In autumn 1989 in al-Ta’if, Saudi Arabia, a majority of the surviving members of the 1972 Lebanese parliament agreed on a political reform document.”1 Within the Ta’if Agreement was the inclusion of most of the heads of militias into the postwar political system, further legitimizing them as big players within Lebanon. In accordance with the Ta’if Accord, the Lebanese president must be from the Maronite Christian community. While the prime minister is Sunni, the parliamentary speaker is Shia. In addition, the deputy speaker of parliament and the deputy prime minister in Lebanon must be Greek Orthodox.2 March 14 Alliance & March 8 Alliance The March 14 Alliance is a coalition of political parties formed in 2005 following the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, whose son Saad Hariri is the alliance’s current leader. -

Why Do March 8 Parties Want Lebanon to Join the Iranian-Syrian Axis?

Artical Name : Why do March 8 parties want Lebanon to join the Iranian-Syrian axis? Artical Subject : Why do March 8 parties want Lebanon to join the Iranian-Syrian axis? Publish Date: 27/08/2017 Auther Name: Future for Advanced Research and Studies Subject : March 8 parties ±particularly Hezbollah ±in support of the Iranian axis have sought rapprochement with Bashar al-Assad¶s regime and they are trying to push the Lebanese state to establish direct political and economic relations with it. March 14 parties, particularly the Lebanese Forces which opposes Syria, objected because Hezbollah¶s attempts aim to help the Syrian regime exit its regional and international isolation, to make it present again in Lebanon and enhance economic cooperation as a path to establish more comprehensive strategic relations. Any rapprochement with the al-Assad regime will deepen divisions in Lebanon and lead to a political crisis which may harm constitutional institutions and lead to tightening American sanctions on Hezbollah in order to harm the Lebanese economy or suspend foreign support for the Lebanese army. Involving Lebanon in the current regional disputes as a player in support of the Iranian axis may subject the country to Israeli aggression.After Minister of Industry Hussein Hajj Hassan (a representative of Hezbollah in the Lebanese government) said he and Minister of Agriculture Ghazi Zaiter (a representative of the Amal Movement in the government), received an invitation from the Syrian minister of Economy and Trade to participate in the International Damascus Exhibition which will be held from August 17 until August 26, some political parties in Lebanon sought rapprochement and cooperation with al-Assad regime to restore political ties. -

A Snapshot of Parliamentary Election Results

ا rلeمtركnزe اCل لبeنsانneي aلbلeدرLا eساThت LCPS for Policy Studies r e p A Snapshot of Parliamentary a 9 1 0 P 2 l i Election Results r y p A c i l Sami Atallah and Sami Zoughaib o P Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. Copyright© 2019 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org A Snapshot of Parliamentary Election Results 1 1 Sami Atallah and Sami Zoughaib The authors would like to thank John McCabe, Ned Whalley, Hayat Sheik, Josee Bilezikjian, Georgia Da gher, and Ayman Tibi for their contributions to this paper. Sami Atallah Sami Atallah is the director of the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS). He is currently leading several policy studies on youth social identity and political engagement, electoral behavior, political and social sectarianism, and the role of municipalities in dealing with the refugee crisis. He is the co-editor of Democracy, Decentralization, and Service Delivery in the Arab World (with Mona Harb, Beirut, LCPS 2015), co-editor of The Future of Oil in Lebanon: Energy, Politics, and Economic Growth (with Bassam Fattouh, I.B. Tauris, 2018), and co-editor of The Lebanese Parliament 2009-2018: From Illegal Extensions to Vacuum (with Nayla Geagea, 2018). -

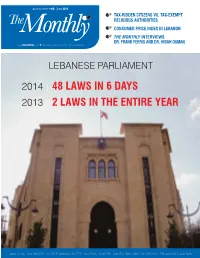

2014 | 48 Laws in 6 Days 2013 | 2 Laws in the Entire Year

issue number 143 |June 2014 TAX-RIDDEN CITIZENS VS. TAX-EXEMPT RELIGIOUS AUTHORITIES CONSUMER PRICE INDEX IN LEBANON THE MONTHLY INTERVIEWS DR. FRANK FERRIS AND DR. HIBAH OSMAN www.iimonthly.com Published by Information International sal LEBANESE PARLIAMENT 2014 | 48 LAWS IN 6 DAYS 2013 | 2 LAWS IN THE ENTIRE YEAR Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros June INDEX 2014 4 LEBANON’S PARLIAMENT 2014: 48 LAWS IN 6 DAYS VS. 2 LAWS IN 2013 10 RENT OF GOVERNMENT PREMISES 12 TAX-RIDDEN CITIZENS VS. TAX-EXEMPT RELIGIOUS AUTHORITIES 13 TAXES AND FEES IN LEBANON 16 CONSUMER PRICE INDEX IN LEBANON 18 LEBANON’S SALARY SCALE BETWEEN RIGHTS, COST AND CONSEQUENCES INFORMATION INTERNATIONAL’S ROUND-TABLE DISCUSSION P: 30 P: 16 20 SALARY SCALE - AMINE SALEH 22 WILL THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC BECOME SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF LA FRANCOPHONIE? 24 ANTOUN SAAD - THE RULE OF MUKHABARAT 26 THE EDUSKUNTA OF FINLAND 28 ANTIBIOTIC COLITIS: DR. HANNA SAADAH 29 FRACTAL MATHEMATICS (2): ANTOINE BOUTROS P: 47 30 INTERVIEW: DR. FRANK FERRIS AND DR. HIBAH OSMAN - “BALSAM” 32 ANTA AKHI- FRATERNITY AND COEXISTENCE 44 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- LEBANON ABDUCTION AND ASSASSINATION OF US 34 DEBUNKING MYTH#82: CLASSICAL MUSIC AMBASSADOR IN LEBANON MAKES BABIES SMARTER 46 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- ARAB WORLD 35 MUST-READ BOOKS: PSALMS OF A LIFETIME THE 1920 IRAQI REVOLUTION MONA BAROUDI AL-DAMLOUJI 47 ON THE