A Clarification and Reformulation of Prevailing Approaches to Product Separability in Franchise Tie-In Sales Minn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dreyer's Grand Ice Cream Business Time Line

Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream Business Time Line: DATE Event Description 4th Origins of ice cream being made… China, Persians faloodeh, Nero in Rome (62 AD) century BC 15th Spanish, Italian royalty and wealthy store mountain ice in pits for summer use Century 16th Ice Cream breakthrough is when Italians learn to make ice by immersing a bucket of Century water in snow and adding potassium nitrate… later just use common salt. 1700s Jefferson and Washington In US serving ice cream 1776 First US ice cream parlor in New York City and American colonists first to use the term ice cream 1832 Augustus Jackson (Black) in Philadelphia adds salt to lower temp. White House chef to a catering business. 1846 Nancy Johnson patented hand-crank freezer 1848 William Young patents an ice cream freezer 1851 Jacob Fussell in Seven Valleys, Pennsylvania established the first large-scale commercial ice cream plant… moved to Baltimore 1870s Development of Industrial Refrigeration by German engineer Carl von Linde 1904 Walk away edible cone at the St Louis World’s Fair 1906 William Dreyer made his first frozen dessert to celebrate his German ship's arrival in America. Made Ice Cream in New York then moves to Northern California began 20 year apprenticeship with ice cream makers like National Ice Cream Company and Peerless Ice Cream. 1921 Dreyer opens own ice creamery in Visalia and one first prize at Pacific Slope Dairy Show. 1920s – Dreyer taught ice cream courses at the University of California and served as an officer in 1930s the California Dairy Industries Association. -

FUND™ Reports [email protected] We Are Constantly Adding More Brands

For more information: FUND™ Reports [email protected] We are constantly adding more brands. 1.800.485.9570 9Round Fitness DQ Teat Jackson Hewit Tax Services Sonny's BBQ Pit AAMCO Transmissions Dunkin Donuts Jamba Juice Sport Clips Ace Hardware Econo Lodge Jersey Mike's Spring‐Green AFC/Doctors Express Edible Arrangements Jet's Pizza SpringHill Suites AIM Mail Center El Pollo Loco Jiffy Lube Steak N Shake Aire Serv Elements Massage Jiffy Lube + Sterling Optical Alphagraphics EmbroidMe Jimmy Johns Suburban Always Best Care European Wax Center KFC Subway Ameriprise Financial Express Employment Kiddie Academy SUPERCUTS Services Professionals Kids 'R' Kids Taco Bell Another Broken Egg Fairfield Inn & Suites KOA franchise campgrounds TeamLogic IT Anytime Fitness Fantastic Sams Koko FitClub The Cleaning Authority Apricot Lane FASTSIGNS Krispy Kreme The Dailey Method Arby's FibreNew kumon The Egg & I Ascend Hotel Collection Figaro's Pizza La Quinta Inn The Grounds Guys Auntie Anne's Firehouse Subs Liberty Tax Service The HoneyBaked Ham Co. Batteries Plus Bulbs Five Guys Burgers Little Caesars and Cafe Bojangle's Five Star Painting Little Ceasars The Learning Experience BrightStar Care Gigi's Cupcakes Maaco The Maids Buffalo Wild Wings Glass Doctor MainStay Suites The Medicine Shoppe Burger King Corporation Go Mini ‐ emerging Marco's Pizza The UPS Store Camp Bow Wow Golden Corral Massage Envy Spa Tim Hortons Canteen Vending Great Clips Massage Heights Title Boxing Club Capriotti's Great Harvest Mathnasium Tropical Smoothie -

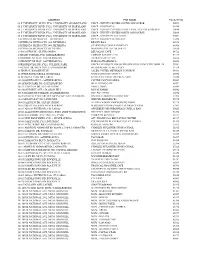

FSE Permit Numbers by Address

ADDRESS FSE NAME FACILITY ID 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER SOUTH CONCOURSE 50891 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - FOOTNOTES 55245 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER EVENT LEVEL STANDS & PRESS P 50888 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER NORTH CONCOURSE 50890 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY PLAZA LEVEL 50892 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, -, BETHESDA HYATT REGENCY BETHESDA 53242 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA BROWN BAG 66933 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY 66506 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, BETHESDA MORTON'S THE STEAK HOUSE 50528 1 DISCOVERY PL, SILVER SPRING DELGADOS CAFÉ 64722 1 GRAND CORNER AVE, GAITHERSBURG CORNER BAKERY #120 52127 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG ASTRAZENECA CAFÉ 66652 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG FLIK@ASTRAZENECA 66653 1 PRESIDENTIAL DR, FY21, COLLEGE PARK UMCP-UNIVERSITY HOUSE PRESIDENT'S EVENT CTR COMPLEX 57082 1 SCHOOL DR, MCPS COV, GAITHERSBURG FIELDS ROAD ELEMENTARY 54538 10 HIGH ST, BROOKEVILLE SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 54491 10 UPPER ROCK CIRCLE, ROCKVILLE MOM'S ORGANIC MARKET 65996 10 WATKINS PARK DR, LARGO KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN #5296 50348 100 BOARDWALK PL, GAITHERSBURG COPPER CANYON GRILL 55889 100 EDISON PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG WELL BEING CAFÉ 64892 100 LEXINGTON DR, SILVER SPRING SWEET FROG 65889 100 MONUMENT AVE, CD, OXON HILL ROYAL FARMS 66642 100 PARAMOUNT PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG HOT POT HERO 66974 100 TSCHIFFELY -

Download a 27-Page PDF of the 2016

1966 • NRN celebrates 50 years of industry leadership • 2016 WWW.NRN.COM APRIL 4, 2016 CONSUMER PICKS THE DEFINITIVE ANNUAL RANKING OF TOP RESTAURANT BRANDS, PAGE 10 TM ove. It isn’t a word often used in businesses, but it is a word often used about businesses. Whether a customer loves your brand, loves your menu, loves your servers or loves your culture translates into whether your business will thrive. Love is a word businesses should get comfortable with. The annual Consumer Picks special report from Nation’s Restau- rant News and WD Partners is a measure of restaurant brand success from the eyes of their guests. Surveying customers to the tune of 37,339 ratings, Lincluding specific data points on 10 restaurant brand attributes like Cleanliness, Value, Service and Craveability, Consumer Picks ranks 173 chains on whether or not their guests are feeling the love. In this year’s report, starting on page 10, there is valuable analysis on top strat- egies to win over the customer, from the simplicity of cleaning the restaurant to the more complex undertaking of introducing an app to provide guests access to quick mobile payment options. Some winning brands relaunched menus and oth- ers redesigned restaurants. It is very clear through this report’s data and operator insights that to satisfy today’s demanding consumer, a holistic approach to your brand — who you are, what you stand for, the menu items you serve, the style in which you serve it and the atmosphere you provide to your guest — is required. This isn’t anything new. -

SBA Franchise Directory Effective March 31, 2020

SBA Franchise Directory Effective March 31, 2020 SBA SBA FRANCHISE FRANCHISE IS AN SBA IDENTIFIER IDENTIFIER MEETS FTC ADDENDUM SBA ADDENDUM ‐ NEGOTIATED CODE Start CODE BRAND DEFINITION? NEEDED? Form 2462 ADDENDUM Date NOTES When the real estate where the franchise business is located will secure the SBA‐guaranteed loan, the Collateral Assignment of Lease and Lease S3606 #The Cheat Meal Headquarters by Brothers Bruno Pizza Y Y Y N 10/23/2018 Addendum may not be executed. S2860 (ART) Art Recovery Technologies Y Y Y N 04/04/2018 S0001 1‐800 Dryclean Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S2022 1‐800 Packouts Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0002 1‐800 Water Damage Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0003 1‐800‐DRYCARPET Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0004 1‐800‐Flowers.com Y Y Y 10/01/2017 S0005 1‐800‐GOT‐JUNK? Y Y Y 10/01/2017 Lender/CDC must ensure they secure the appropriate lien position on all S3493 1‐800‐JUNKPRO Y Y Y N 09/10/2018 collateral in accordance with SOP 50 10. S0006 1‐800‐PACK‐RAT Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S3651 1‐800‐PLUMBER Y Y Y N 11/06/2018 S0007 1‐800‐Radiator & A/C Y Y Y 10/01/2017 1.800.Vending Purchase Agreement N N 06/11/2019 S0008 10/MINUTE MANICURE/10 MINUTE MANICURE Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 1. When the real estate where the franchise business is located will secure the SBA‐guaranteed loan, the Addendum to Lease may not be executed. -

August 6, 2020 the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell Speaker Majority

August 6, 2020 The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Charles E. Schumer Speaker Majority Leader Minority Leader Minority Leader U.S. Senate U.S. Senate Washington D.C. 20510 Washington D.C. 20510 The Honorable Marco Rubio The Honorable Ben Cardin Chairman, Committee on Small Business & Ranking Member, Committee on Small Business Entrepreneurship & Entrepreneurship U.S. Senate U.S. Senate Washington D.C. 20510 Washington D.C. 20510 Dear Majority Leader McConnell, Minority Leader Schumer, Chairman Rubio, and Ranking Member Cardin We write to you on behalf of our independent franchise owners regarding recent proposals to further help small businesses like theirs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The undersigned brands represent a broad segment of the franchise sector, which employs roughly 8 million American workers at 733,000 locations. The franchise business model has led to success and upward mobility for both franchise owners and employees in more than 300 business lines and across demographic groups. Indeed, franchising is more diverse than non-franchise businesses: according to U.S. Census data, nearly 30 percent of franchise businesses are minority-owned, compared to 18 percent of non-franchised businesses. Our franchisees truly appreciate your leadership in Congress’s historic response to the COVID-19 crisis. The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), in conjunction with increased support of our health care system, has enabled many franchise small businesses to remain operational and retain employees. However, the future for these same small businesses is anything but settled. Continuous operation at reduced capacity – and in many cases, extended business closures – has led to precipitous drops in revenue. -

First U.S. Franchise Opens in Libya

- 1 - August 7, 2012 First U.S. franchise opens in Libya By Kendal H. Tyre and Diana Vilmenay-Hammond After two years of planning and one false start, U.S.-based baked goods chain Cinnabon became the first U.S. franchise to open a store in Libya on July 2, 2012. The franchise will sell signature Cinnabon products alongside Carvel-brand ice cream and cakes. Focus Brands International owns the Cinnabon and the Carvel brands. The 7,500-square-foot bakery-cafe in downtown Tripoli is located in the city’s business district and was originally set to open in early 2011. A shipment of product was already on its way but the launch was scrapped when the Libyan civil war broke out which ousted former leader Muammar Gaddafi and sparked bloody protests. In addition to the traditional menu items, the Tripoli location will offer a wide variety of locally created sandwiches, salads, and other baked goods as well as cakes and pies that are imported from Italy. The company began considering an expansion into Libya two years ago when U.S. sanctions on the country were easing. The company had received numerous franchise inquiries from Libyans living overseas. Ultimately, the brothers Arief and Ahmed Swaidek opened the co-branded location as franchisees. They plan to open 10 more Cinnabon locations in Libya over the next five years, with another one coming later in 2012. They also plan to open more Carvel units and have also signed on to bring Moe’s Southwest Grill locations to Libya. According to the company, in the first week of its opening, the Tripoli Cinnabon store logged $45,000 USD in sales. -

Restaurant Compliance July 2

Accessible Restaurant Survey 7/15/2019 Sl Business Address Compliance No. Complaint Non-Compliant 1 Just Salad 233 Broadway, New York, NY 10279 X 2 Fowler and Wells 5 Beekman St, New York, NY 10038 X 3 Birch Coffee 8 Spruce St, New York, NY 10038 X 4 Wxyz Bar, 49 Ann St, New York, NY 10038 X 5 Poke Bowl 104 Fulton St, New York, NY10038 X 6 Sakura Of Japan 73 Nassau St, New York, NY 10038 X 7 Dunkin' Donuts 80 John St, New York, NY10038 X 8 Hole In The Wall 15 Cliff St, New York, NY 10038 X 9 Feed Your Soul Café 14 Wall St, New York, NY 10005 X 10 Black Fox Coffee Co 70 Pine St, New York, NY 10270 X 11 Fairfield Inn & Suites 161 Front St, New York, NY 10038 X 12 Delivery Only 126 Pearl St, New York, NY 10005 X 13 Bluestone Lane 90 Water St, New York, NY 10005 X 14 Industry Kitchen 70 South St, New York, NY 10005 X 15 Just Salad 90 Broad St, New York, NY 10004 X 16 Hale and Hearty 111 Fulton St, New York, NY 10038 X 17 Ainsworth 121 Fulton St, New York, NY 10038 X 18 Keste Fulton 66 gold street, New York, NY 10038 X 19 Temple Court 5 Beekman St, New York, NY 10038 X 20 Joe's Pizza 124 Fulton St, New York, NY 10038 X 21 Potbelly Sandwich Shop 127 Fulton St, New York, NY 10038 X 22 GRK Fresh Greek 111 Fulton St, New York, NY 10038 X 23 Plaza Deli 127 John St, New York, NY 10038 X 24 Flavors Café 175 Water St, New York, NY 10038 X 25 Roast Kitchen 199 Water St, New York, NY 10038 X 26 Mamam 239 Centre St, New York, NY 10013 X 27 Flour Shop 177 Lafayette St, New York, NY 10013 X 28 Troquet 155 Grand St, New York, NY 10013 X 29 109 West Broadway -

Roark Capital Group Scoops up Carvel Ice Cream Brand in Deal with Investcorp

Contact: Scott Pressly Todd Fogarty (Investcorp) Roark Capital Group Kekst and Company (404) 942-3535 (212) 521-4854 [email protected] [email protected] Roark Capital Group Scoops Up Carvel Ice Cream Brand in Deal with Investcorp --Roark Capital Group to gain national distribution for Carvel’s premium ice cream - --Growth in both franchise/food service locations and supermarket outlets to be emphasized- Atlanta, GA, December 10, 2001 - Roark Capital Group, a private equity firm focused on acquiring multi- unit businesses and brand management companies, has purchased a controlling interest in Carvel Corporation, a leading ice cream distributor and franchisor. Roark Capital Group purchased preferred stock that is convertible into a majority ownership stake in Carvel while Investcorp, the previous owner, invested additional equity and retained a minority position in the company. As part of the transaction, Neal Aronson, founder and president of Roark Capital Group, has become Chairman of the Board of Directors for Carvel. “Carvel has outstanding brand recognition and customer loyalty primarily in the northeast and Florida,” commented Aronson. “Our goal is to expand Carvel’s devoted and loyal following to a national audience by increasing the resources available to the company in key areas such as sales, marketing, service and research & development.” Founded in 1934, Carvel is one of the oldest and most recognizable names in the ice cream industry. In its core markets, the Carvel brand enjoys 98% brand awareness and 90% intent-repeat purchase. The company has more than 400 franchised and food service locations serving premium fountain style products including cups, cones, sundaes and shakes and over 5,000 supermarket outlets for its famous ice cream cakes. -

KBRA Assigns the Final Ratings to FOCUS Brands Funding LLC – Series 2018-1 Senior Secured Notes and Downgrades the Series 2017-1 Senior Secured Notes

KBRA Assigns the Final Ratings to FOCUS Brands Funding LLC – Series 2018-1 Senior Secured Notes and Downgrades the Series 2017-1 Senior Secured Notes NEW YORK, NY (October 29, 2018) – Kroll Bond Rating Agency (KBRA) announces the final ratings to one class of notes of FOCUS Brands Funding LLC, Carvel Funding LLC, McAlister’s Funding LLC, and Jamba Juice Funding LLC, a whole business securitization. Focus Brands Inc. (“FOCUS” or the “Company”) completed its first whole business securitization (“WBS”) in April 2017. The transaction is a master trust, and the Senior Secured notes, Series 2018-1 Class A-2 (the “Series 2018-1 Notes”) represent the Company’s second securitization within the trust. FOCUS Brands Funding LLC (the “Master Issuer”), Carvel Funding LLC, McAlister’s Funding LLC and Jamba Juice Funding LLC (together, the “Co- Issuers”) are issuing $300 million of Series 2018-1 Notes (pari passu with the Series 2017-1, Class A-2 Notes). In connection with the issuance, the Company is contributing additional collateral related to Jamba Juice. The Company is the franchisor and operator of branded locations under the brands Auntie Anne’s, Carvel, Cinnabon, Jamba Juice, McAlister’s Deli, Moe’s Southwest Grill and Schlotzsky’s. The collateral includes existing and future franchise and development agreements, existing and future company-operated location royalties, licensing fees, vendor payments and fees (excluding Jamba Juice), intellectual property, and related revenues. The proceeds from the offered notes are being used to repay the outstanding principal amount of the Series 2017-1, Class A-1 Notes, pay transaction fees and expenses, fund certain accounts, and may also be used to fund shareholder distributions. -

GEORGETOWN PREP Nine Miles from "The Hilltop" on Route 240

A New England Mutual agent ANSWERS S01l1E QUESTIONS about sales training • • Ill life Insurance ~lORE THAN 900 New England Mutual agents like Suppose I join New England Mutual as a field repre· George Graves (Georgetown '49) are college alumni. sentative. How would they start They come from all over the country. George is only 29 training me? years o ld, b ut already he's won m embership in o ur "First, you'd get basic training in your own agency- both L eaders' A ssociation. H e says his success in selling life theory and field work. Then, after a few months of selling insurance is a direct result o f N ew England Mutual's comprehensive course of sales training. under expert guidance, comes a comprehensive Home Of fice course in Boston." How soon can I expect this training to pay off? "I'll give you an example of five new men at one of our eastern agencies. Young fellows, 24 t o 31 years old. Only one had any previous experience in life insurance. By the end of the first year their in comes ranged from $3532 to $5645. Wi th renewal commissions, first year earnings would be from $5824 to $9702. The average: $7409." Can a man continue his study of life insurance after those first two courses? "He most certainly can. The company will next instruct you in the use of its 'Coordinated E tates' programming service. Then y ou go on t o 'Advanced Underwriting', which r elates in urance to business u es, estate planning and taxation problems. -

Sonic Capital LLC (Series 2020-1)

Presale: Sonic Capital LLC (Series 2020-1) January 7, 2020 PRIMARY CREDIT ANALYST Preliminary Ratings Christine Dalton New York Class Preliminary rating Balance (mil. $) Anticipated maturity Legal maturity (years) (1) 212-438-1136 A-1 (VFN) BBB (sf) 25.00 January 2025 30 christine.dalton @spglobal.com A-2-I BBB (sf) 150.00 January 2027 30 SECONDARY CONTACTS A-2-II BBB (sf) 700.00 January 2030 30 Kate R Scanlin Note: This presale report is based on information as of Jan. 7, 2020. The ratings shown are preliminary. Subsequent information may result in New York the assignment of final ratings that differ from the preliminary ratings. Accordingly, the preliminary ratings should not be construed as (1) 212-438-2002 evidence of final ratings. This report does not constitute a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell securities. VFN--Variable funding notes. kate.scanlin @spglobal.com Jie Liang, CFA Executive Summary New York (1) 212-438-8654 Sonic Capital LLC's series 2020-1 is an $875.00 million corporate securitization of the Sonic Corp. jie.liang business that may be increased to $925.00 million subject to certain conditions. From the debt @spglobal.com issuance, a portion of the proceeds will be used to repay the amount outstanding on the series Matthew R Howard 2013-1 class A-2 notes, the amount outstanding on the series 2016-1 class A-2 notes, the Chicago outstanding balance on the IRB Holding Corp. revolver, and the amount outstanding on Arby's + 1 (312) 233 7035 series 2015-1 and 2016-1 class A-1 notes.