The Liar the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All in the Timing, by David Ives

All in the Timing, by David Ives Sure Thing “Bill” - Aidan Loretz “Betty” - Ava Moss Words, Words, Words “Swift” – Tristen Gray “Milton” - Mattie Mount “Kafka” - Ella Naylor Universal Language “Dawn” - Nita Allen “Don” - Perrion Porter Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread “Woman” - Alison Clodfelter “Man” – Perrion Porter “Baker” – Annie Cowley “Philip Glass”- Christopher Beasley The Philadelphia “Al” –Jessica Dutton “Waitress” – Rori Cummings “Mark” – Christopher Beasley Variations on the Death of Trotsky “Trotsky” – Aidan Loretz “Mrs. Trotsky” – Starr James “Ramon” – Tyshanna Hayes The show runs 90 minutes with no intermission. Director’s Notes Director/Choreographer – Jesse Graham Galas Stage Manager – AE Ray All in the Timing is, at its core, a series of plays Assistant Stage Managers – Ava Moss, Samantha Harriss asking, “What if?” What if you got the chance to Technical Director – Josh Webb start over every time you said the wrong thing? Lights/Set Designer – Josh Webb What if you put some monkeys in a room with Assistant Technical Director – Mike Merluzzi some typewriters…could they really come up with Costume Designers one of the greatest plays ever written? What if “Sure Thing”– Lawson Lee everyone spoke the same language? Would that “Words, Words, Words” – Chevez Smith end all communication breakdowns forever? What “Universal Language” – Cameron McWhorter if you could get inside the mind of composer Philip “Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread” – Jolee Masson Glass…has the smallest act of buying a loaf of “The Philadelphia” – Starr -

The School for Lies

—The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act I, Scene iii THE SCHOOL FOR LIES Contents Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 8 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST 312.595.5600 events, plays and players www.chicagoshakes.com ©2012 Point of View Chicago Shakespeare Theater 12 All rights reserved. Director Barbara Gaines and Playwright David Ives ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Barbara Gaines discuss The School for Lies EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Criss Henderson PICTURED, COVER AND ABOVE: Deborah Hay and Ben Carlson, Cast 21 photo by Bill Burlingham Playgoer’s Guide 22 Profiles 23 Scholar’s Notes 34 Ira Murfin celebrates disjunction—and our delight— in The School for Lies www.chicagoshakes.com 3 unforgettable . Hyatt is proud to sponsor Chicago Shakespeare Theater. We’ve supported the theater since its inception and believe one unforgettable performance deserves another. Experience distinctive design, extraordinary service and award-winning cuisine at every Hyatt worldwide. For reservations, call or visit hyatt.com. HYATT name, design and related marks are trademarks of Hyatt Corporation. ©2012 Hyatt Corporation. All rights reserved. HCM29411.01.a_Shakespeare_Ad.indd 1 1/26/12 10:24 AM a messaGe from Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson raymond f. mcCaskey Artistic Director Executive Director Chair, Board of Directors DEAR FRIENDS Welcome to Chicago Shakespeare Theater! Over the years, our artists have delighted audiences with plays that are vibrant, accessible and bold in their exploration of contemporary themes through classical literature. Today’s production has provided our artistic collective with the opportunity to flip this model on its head by producing a modern play viewed through a classical lens. -

March 21, 2013 MEDIA CONTACT: Susan Yannetti Public Relations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: March 21, 2013 MEDIA CONTACT: Susan Yannetti Public Relations Manager [email protected] Phone: 941.351.9010 ext. 4800 Mobile: 941.735.1131 STEAMY NEW COMEDY VENUS IN FUR HEATS UP THE STAGE AT ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE (SARASOTA, March 21, 2013) — It’s more than just the Florida sun that’s sizzling at Asolo Rep this spring. The must-see hit of the recent Broadway season, Venus in Fur, written by theatrical mastermind David Ives opens in the Historic Asolo Theater Friday, April 5 and runs through April 28, 2013. Two preview performances are scheduled for April 3 and 4. Tea Alagić, an exciting new talent originally from the Czech Republic, directs this wickedly entertaining comedy that explores the complex relationship between an aspiring stage actress and her playwright/director. Venus in Fur is a hot ticket in every sense. This alluring tale of love, lust, and literature illuminates the ultimate battle of the sexes. Vanda is the far-from-typical young actress who arrives to audition for the lead in playwright Thomas’ adaptation of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 erotic novel, “Venus in Furs.” As her audition proceeds, Vanda’s continually shifting personas, accents, moods, expressions and apparent (and not-so-apparent) intentions engage Thomas in an emotionally charged game of cat and mouse. Is art imitating life? Or is it the other way around? As the lines between reality and fantasy become blurred the audience is swept up in Thomas’ seduction. The Broadway production made an instant star of its leading actress, Nina Arianda, who won the Tony Award for Best Actress in 2012. -

Venus in Fur by David Ives

VENUS IN FUR reprint file.qxd 10/7/2014 12:31 PM Page i VENUS IN FUR BY DAVID IVES # # DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. VENUS IN FUR reprint file.qxd 10/7/2014 12:31 PM Page 2 VENUS IN FUR Copyright © 2012, David Ives All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of VENUS IN FUR is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for VENUS IN FUR are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

Iago Parla Unamunda: Understanding a Nonsense Language

Iago Parla Unamunda: Understanding a nonsense language By Emily Gasser Swarthmore College Abstract If you walked into a room and were greeted by an exclamation of “Velcro! Police, comintern. Harvardyu?”, how would you respond? Probably with a puzzled look, possibly followed by, “Fine thanks, and you?” Much research has been done in how the human mind understands a known language. But though nonsense languages have a rich literary history, there is much less written on how we understand and process nonsense languages, those for which there is little or no existing mental framework. This thesis explores how this sort of linguistic input might be processed and understood, focusing in particular the case of Unamunda, the nonsense language created by David Ives in his short play “The Universal Language” (1994). Unamunda consists of a combination of English words assigned new meanings, proper nouns (also assigned new meanings), plays on foreign words and phrases, and nonsense words. Its syntax is very nearly that of English, with occasional variations on word order. Though no one listening to Unamunda being spoken onstage has any prior familiarity with its lexicon or grammar, it is still possible to understand the utterances with little extra effort. After an overview of some theories and models of some various aspects of word recognition, including the effects of context on lexical decision-making, the clues to meaning supplied by syntactic structures, and phonotactic neighborhood activation, I move on to a discussion of my own experiment, in which subjects were asked to translate written, spoken, and video segments of Unamunda into English.* Introduction A guy goes into a restaurant, sits down, and orders Eggs Benedict. -

THE NATURAL Her Director

out for an Off Broadway production of a BACKSTAGE CHRONICLES new play by David Ives, “Venus in Fur,” the story of a fierce and funny psychosex- ual power struggle between an actress and THE NATURAL her director. Arianda had fallen in love with the heroine of the play, Vanda, an Nina Arianda: Broadway’s new star. aspiring actress, who—in a scenario fa- miliar to Arianda—arrives at a rehearsal BY JOHN LAHR hall to audition for a part she has no chance of getting. In Vanda’s case, it was a part in an adaptation of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s classic about the erotic forms of hate, “Venus in Furs.” “Am I too late? I’m too late, right? Fuck. Fuck!” Vanda says as she arrives onstage, hoping to read for the role of Vanda von Dunayev, an emancipated nineteenth-century Con- tinental woman. The dramatic pitch of Vanda’s opening line captured Arianda’s imagination. “I’d never read something and been so enthralled by where a charac- ter could go,” she told me recently. “The humor is what always gets me. The com- mitment she has to what she’s doing or saying. There’s no comment. She lives it.” The actress who plays Vanda is re- quired to metamorphose from a twenty- first-century street-smart New Yorker into the nineteenth-century European cosmopolitan of the Sacher-Masoch play- within-the-play, and even have the emo- tional extravagance to suggest the goddess Aphrodite, who emerges as a sort of fab- ulous eleven-o’clock number. -

Hugh Dancy & the Phenomenal Nina Arianda in the Psycho

BATTLE OF THE SEXES: (left to right) Hugh Dancy & the phenomenal Nina Arianda in the psycho-sexual thriller, Venus in Fur. Photo: Joan Marcus Theater Review Venus in Fur: S&M power play, mind games VENUS IN FUR Written by David Ives Directed by Walter Bobbie Samuel J. Friedman Theatre 261 West 47th Street (212-239-6200),www.ManahattanTheatreClub.com By David NouNou Control, power, dominance all play major factors in David Ives’ provocative new dramedy, Venus In Fur. Who offers it and who uses it? Who ultimately has that power and control; the submissive who is giving you the power or the master who has been given that power? Until ultimately the lines become so blurred and, thus, the power struggle begins. Set in a rehearsal hall, Thomas (Hugh Dancy), a director and playwright, has auditioned some 35 actresses for the female lead in the play he has written, based on the classic 1870 erotic Austrian novella Venus in Furs by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (the namesake of the term “sadomasochism"). Not one of the actresses Thomas has auditioned has the qualities for which he is searching: beauty, grace, strength, power, and a great command of the English language. As Thomas is calling it a day, and conversing with his girlfriend on his cell phone, in bursts Vanda (Nina Arianda), an actress, totally disheveled from the rainstorm outside, late for her audition, and the last person you would expect to qualify for the role. Dismissive he is, persistent she is, until finally he allows her to read three pages of the play just to appease her. -

Laughter and Canapes: Burbage’S School for Lies Is

Laughter and Canapes: Burbage’s School for Lies is a Fabulous Farce “One ought to look a good deal at oneself before thinking of condemning others.” ~ Moliere Photo credit: Maggie Hall There are few things better in the theater than a company that knows which strengths to put forth and when to call upon them. Burbage Theatre Company has just moved into a brand new space at 59 Blackstone Avenue in Pawtucket, not far from their last venue, and they’ve put together the perfect production to kick off their ninth season in this stunning new location. If you want to hear more about the theater, check back soon for a feature on BTC’s new space, but for now, let’s talk about School for Lies. Based on Moliere’s The Misanthrope and adapted by the Modern King of Clever, David Ives, it’s a delicious cocktail of an evening that satisfies the mind and busts the gut. The Misanthrope was first performed in 1666 by the King’s Players in Paris, and is still one of Moliere’s most produced works today. David Ives was born nearly 300 years later, and became known for being a sophisticated playwright who was equally comfortable writing for blue collar philosophers or flies or Trotsky. His adaptations include A Flea in Her Ear, The Heir Apparent and Pierre Corneille’s The Liar, which had a stellar production at the William Hall Library in Cranston done by none other than Burbage itself — and it’s a joy to see them return to another classic through the zany lens of Ives. -

University of Hawai'i at Hilo Theatre

UH Hilo Performing Arts Department Master Production List 1979- 2020 Musicals GIVE MY REGARDS TO BROADWAY - A Musical Revue AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS by Gian Carlo Menotti CAROUSEL by Rodgers and Hammerstein OLIVER by Lionel Bart SOUTH PACIFIC by Rodgers and Hammerstein MY FAIR LADY by Lerner and Loewe FLOWER DRUM SONG by Rodgers and Hammerstein FIDDLER ON THE ROOF by Stein and Bock THE SOUND OF MUSIC by Rodgers and Hammerstein CABARET by Kander and Ebb I DO! I DO! by Jones and Schmidt YOU’RE A GOOD MAN CHARLIE BROWN by Clark Gesner archy and mehitabel by Joe Darion and Mel Brooks AN EVENING OF OPERA SCENES, Conceived by Margaret Harshbarger JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Weber** THE MIKADO by Gilbert and Sullivan WEST SIDE STORY by Bernstein and Sondheim (1988) I’M GETTING MY ACT TOGETHER AND TAKING IT ON THE ROAD, by Joan Micklin Silver & Julianne Boyd ANNIE by Thomas Meehan A.....MY NAME IS ALICE by Joan Micklin Silver, Julianne Boyd LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS by Ashman & Menken NUNSENSE by Dan Goggin MUSIC MINUS ONE by George Furth, starring Leslie Uggams* * World Premiere EASY STREET: AN AMERICAN DREAM, by Wendell Ing * * World Premiere CAMELOT by Lerner and Lowe WORKING, THE MUSICAL A CHRISTMAS CAROL, by Bedloe, Wood, & Shapcott AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISTORS, by Gian-Carolo Menotti SWEENEY TODD, by Stephen Sondheim INTO THE WOODS, by Stephen Sondheim GUYS AND DOLLS, by Frank Loesser A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC, by Stephen Sondheim COMPANY, by Stephen Sondheim 100 YEARS OF BROADWAY, A Musical Revue OKLAHOMA, by Rodgers -

Arkansas Repertory Theatre

ARKANSAS REPERTORY THEATRE Study Guide Prepared by Robert Neblett October 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Play 4 4 Characters 5 Synopsis 7 A word with Artistic Director The Creators 8 8 Playwright - Moliére 10 Translaptation - David Ives 11 About the Original Q&A with Scenic Designer 12 Costumes designed by Historical Context 15 Rafael Colon Castanera The Theatre of Moliére 17 In the Classroom 18 18 Activities 19 Questions for Writing and Discussion 20 Vocabulary 21 About Us NOTE FOR EDUCATORS: Throughout this Study Guide you will find words, names and phrases in bold type. These items are key terms and phrases to a better understanding of the world and context of The School for Lies. These items are suggestions for further research and study among your students, both before and after you attend the performance at The Rep. 2 AN INTRODUCTION… IN COUPLETS! This Study Guide your students will maintain Does nothing to give power to their brains. But you as a good teacher will amaze Your classes with a great knowledge of plays Perform’d by the Arkansas Repertory And they will laud you with high praise and glory. Monsieur Molière wrote the original Of which this text contains but minimal. The prizèd writer known as David Ives Has writ this play in meter made of fives And from its source taken a long vacation With his coin’d term - he calls it "translaptation." Adapting and translating classic text May leave some scholars feeling rather vexed. He’s left the French on the cutting room floor, Afraid of how your students it would bore. -

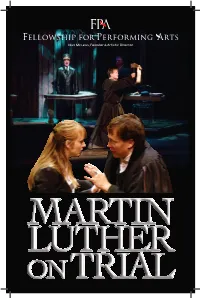

MARTIN LUTHER on TRIAL Max Mclean, Founder & Artistic Director Presents MARTIN LUTHER on TRIAL Written by Chris Cragin-Day & Max Mclean

Max McLean, Founder & Artistic Director MARTIN LUTHER ON TRIAL Max McLean, Founder & Artistic Director presents MARTIN LUTHER ON TRIAL Written by Chris Cragin-Day & Max McLean Featuring Mark Boyett Kersti Bryan Paul DeBoy John FitzGibbon Jamil A.C. Mangan Fletcher McTaggart Set Design Costume Design Lighting Design Original Music & Sound Design Kelly James Tighe Nicole Wee Geoffrey D. Fishburn Quentin Chiappetta Marketing, Advertising & Press Relations Digital Advertising Casting Director Cheryl Anteau The Pekoe Group Carol Hanzel Production Manager Technical Director Stage Manager General Management Lew Mead Katie Martin Alayna Graziani Aruba Productions Executive Producer Ken Denison Directed by Michael Parva The performance will run two hours and 10 minutes with one 15-minute intermission. Please turn off all electronic devices before the performance begins. Thank you. 3 CAST AND LOCATIONS CAST (In Order of Appearance) Paul DeBoy ..............................................................................................................................The Devil Kersti Bryan ............................................................................................................... Katie Von Bora John FitzGibbon .....................................................................................................................St. Peter Mark Boyett ..............................Hitler, St. Paul, Josel, Freud, Hans Luther & Pope Francis Fletcher McTaggart .................................................................................................. -

Tony Vezner C/O Concordia University, 1530 Concordia West, Irvine, CA 92612, (815) 985 8302 Cell, E-Mail: [email protected]

Tony Vezner c/o Concordia University, 1530 Concordia West, Irvine, CA 92612, (815) 985 8302 cell, E-mail: [email protected] Education 1992 M.F.A. - Directing, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 1989 B.A. - English and Theatre Arts, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Other Studies 1987 University of Birmingham at Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Centre, Stratford-on-Avon, England Employment History 2007- Associate Professor, Department of Theatre, Concordia University, Irvine, CA Serving in this four person department which has thirty-five majors and mounts a season of five productions in its black box space and 500 seat amphitheater. Promoted to the rank of associate professor in 2011. Curriculum and Instruction responsibilities have included: ñ Teaching the following courses in the curriculum: THR 101: Experiences in Theatre (general education) THR 111: Experiences in Theatre (general education) THR 251: Introduction to Theatre (dramatic literature/general education) THR 262: Acting II (Greek and Comedy of Manners – changed in 2011 to Realism) THR 351: Directing I THR 371: Acting III (Shakespeare, Chekhov, Beckett, Pinter, Mamet) THR 443: Contemporary Theatre and Culture (dramatic literature/history) THR 451: Directing II (styles) THR 452: Advanced Script Analysis WRT 337: Writing for the Stage and Screen ñ Mentoring senior directing projects (THR 498 – Theatre Showcase, a 3 credit hour individual study course) which culminate in full productions of one-act plays: One Egg by Babette Hughes (2007) directed by Dominick