An Evolutionary Heuristic for Human Enhancement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heidegger, Personhood and Technology

Comparative Philosophy Volume 2, No. 2 (2011): 23-49 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 www.comparativephilosophy.org THE FUTURE OF HUMANITY: HEIDEGGER, PERSONHOOD AND TECHNOLOGY MAHON O‟BRIEN ABSTRACT: This paper argues that a number of entrenched posthumanist positions are seriously flawed as a result of their dependence on a technical interpretive approach that creates more problems than it solves. During the course of our discussion we consider in particular the question of personhood. After all, until we can determine what it means to be a person we cannot really discuss what it means to improve a person. What kinds of enhancements would even constitute improvements? This in turn leads to an examination of the technical model of analysis and the recurring tendency to approach notions like personhood using this technical model. In looking to sketch a Heideggerian account of personhood, we are reaffirming what we take to be a Platonic skepticism concerning technical models of inquiry when it comes to certain subjects. Finally we examine the question as to whether the posthumanist looks to apply technology‟s benefits in ways that we have reflectively determined to be useful or desirable or whether it is technology itself (or to speak as Heidegger would – the “essence” of technology) which prompts many posthumanists to rely on an excessively reductionist view of the human being. Keywords: Heidegger, posthumanism, technology, personhood, temporality A significant number of Posthumanists1 advocate the techno-scientific enhancement of various human cognitive and physical capacities. Recent trends in posthumanist theory have witnessed the collective emergence, in particular, of a series of analytically oriented philosophers as part of the Future of Humanity Institute at O‟BRIEN, MAHON: IRCHSS Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Philosophy, University College Dublin, Ireland. -

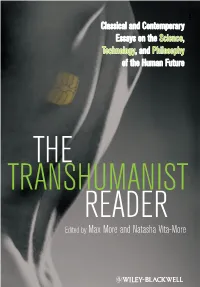

The Transhumanist Reader Is an Important, Provocative Compendium Critically Exploring the History, Philosophy, and Ethics of Transhumanism

TH “We are in the process of upgrading the human species, so we might as well do it E Classical and Contemporary with deliberation and foresight. A good first step is this book, which collects the smartest thinking available concerning the inevitable conflicts, challenges and opportunities arising as we re-invent ourselves. It’s a core text for anyone making TRA Essays on the Science, the future.” —Kevin Kelly, Senior Maverick for Wired Technology, and Philosophy “Transhumanism has moved from a fringe concern to a mainstream academic movement with real intellectual credibility. This is a great taster of some of the best N of the Human Future emerging work. In the last 10 years, transhumanism has spread not as a religion but as a creative rational endeavor.” SHU —Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics, University of Oxford “The Transhumanist Reader is an important, provocative compendium critically exploring the history, philosophy, and ethics of transhumanism. The contributors anticipate crucial biopolitical, ecological and planetary implications of a radically technologically enhanced population.” M —Edward Keller, Director, Center for Transformative Media, Parsons The New School for Design A “This important book contains essays by many of the top thinkers in the field of transhumanism. It’s a must-read for anyone interested in the future of humankind.” N —Sonia Arrison, Best-selling author of 100 Plus: How The Coming Age of Longevity Will Change Everything IS The rapid pace of emerging technologies is playing an increasingly important role in T overcoming fundamental human limitations. The Transhumanist Reader presents the first authoritative and comprehensive survey of the origins and current state of transhumanist Re thinking regarding technology’s impact on the future of humanity. -

Global Catastrophic Risks Survey

GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS SURVEY (2008) Technical Report 2008/1 Published by Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford University Anders Sandberg and Nick Bostrom At the Global Catastrophic Risk Conference in Oxford (17‐20 July, 2008) an informal survey was circulated among participants, asking them to make their best guess at the chance that there will be disasters of different types before 2100. This report summarizes the main results. The median extinction risk estimates were: Risk At least 1 million At least 1 billion Human extinction dead dead Number killed by 25% 10% 5% molecular nanotech weapons. Total killed by 10% 5% 5% superintelligent AI. Total killed in all 98% 30% 4% wars (including civil wars). Number killed in 30% 10% 2% the single biggest engineered pandemic. Total killed in all 30% 10% 1% nuclear wars. Number killed in 5% 1% 0.5% the single biggest nanotech accident. Number killed in 60% 5% 0.05% the single biggest natural pandemic. Total killed in all 15% 1% 0.03% acts of nuclear terrorism. Overall risk of n/a n/a 19% extinction prior to 2100 These results should be taken with a grain of salt. Non‐responses have been omitted, although some might represent a statement of zero probability rather than no opinion. 1 There are likely to be many cognitive biases that affect the result, such as unpacking bias and the availability heuristic‒‐well as old‐fashioned optimism and pessimism. In appendix A the results are plotted with individual response distributions visible. Other Risks The list of risks was not intended to be inclusive of all the biggest risks. -

What Is the Upper Limit of Value?

WHAT IS THE UPPER LIMIT OF VALUE? Anders Sandberg∗ David Manheim∗ Future of Humanity Institute 1DaySooner University of Oxford Delaware, United States, Suite 1, Littlegate House [email protected] 16/17 St. Ebbe’s Street, Oxford OX1 1PT [email protected] January 27, 2021 ABSTRACT How much value can our decisions create? We argue that unless our current understanding of physics is wrong in fairly fundamental ways, there exists an upper limit of value relevant to our decisions. First, due to the speed of light and the definition and conception of economic growth, the limit to economic growth is a restrictive one. Additionally, a related far larger but still finite limit exists for value in a much broader sense due to the physics of information and the ability of physical beings to place value on outcomes. We discuss how this argument can handle lexicographic preferences, probabilities, and the implications for infinite ethics and ethical uncertainty. Keywords Value · Physics of Information · Ethics Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the Global Priorities Institute for highlighting these issues and hosting the conference where this paper was conceived, and to Will MacAskill for the presentation that prompted the paper. Thanks to Hilary Greaves, Toby Ord, and Anthony DiGiovanni, as well as to Adam Brown, Evan Ryan Gunter, and Scott Aaronson, for feedback on the philosophy and the physics, respectively. David Manheim also thanks the late George Koleszarik for initially pointing out Wei Dai’s related work in 2015, and an early discussion of related issues with Scott Garrabrant and others on asymptotic logical uncertainty, both of which informed much of his thinking in conceiving the paper. -

Sharing the World with Digital Minds1

Sharing the World with Digital Minds1 (2020). Draft. Version 1.8 Carl Shulman† & Nick Bostrom† [in Clarke, S. & Savulescu, J. (eds.): Rethinking Moral Status (Oxford University Press, forthcoming)] Abstract The minds of biological creatures occupy a small corner of a much larger space of possible minds that could be created once we master the technology of artificial intelligence. Yet many of our moral intuitions and practices are based on assumptions about human nature that need not hold for digital minds. This points to the need for moral reflection as we approach the era of advanced machine intelligence. Here we focus on one set of issues, which arise from the prospect of digital minds with superhumanly strong claims to resources and influence. These could arise from the vast collective benefits that mass-produced digital minds could derive from relatively small amounts of resources. Alternatively, they could arise from individual digital minds with superhuman moral status or ability to benefit from resources. Such beings could contribute immense value to the world, and failing to respect their interests could produce a moral catastrophe, while a naive way of respecting them could be disastrous for humanity. A sensible approach requires reforms of our moral norms and institutions along with advance planning regarding what kinds of digital minds we bring into existence. 1. Introduction Human biological nature imposes many practical limits on what can be done to promote somebody’s welfare. We can only live so long, feel so much joy, have so many children, and benefit so much from additional support and resources. Meanwhile, we require, in order to flourish, that a complex set of physical, psychological, and social conditions be met. -

Global Catastrophic Risks

Global Catastrophic Risks Edited by Nick Bostrom Milan M. Cirkovic OXPORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents Acknowledgements ν Foreword vii Martin J. Rees 1 Introduction 1 Nick Bostrom and Milan M. Cirkoviô 1.1 Why? 1 1.2 Taxonomy and organization 2 1.3 Part I: Background 7 1.4 Part II: Risks from nature 13 1.5 Part III: Risks from unintended consequences 15 1.6 Part IV: Risks from hostile acts 20 1.7 Conclusions and future directions 27 Part I Background 31 2 Long-term astrophysics! processes 33 Fred C. Adams 2.1 Introduction: physical eschatology 33 2.2 Fate of the Earth 34 2.3 Isolation of the local group 36 2.4 Collision with Andromeda 36 2.5 The end of stellar evolution 38 2.6 The era of degenerate remnants 39 2.7 The era of black holes 41 2.8 The Dark Era and beyond 41 2.9 life and information processing 43 2.10 Conclusion 44 Suggestions for further reading 45 References 45 3 Evolution theory and the future of humanity 48 Christopher Wills· 3.1 Introduction 48 3.2 The causes of evolutionary change 49 xiv Contents 3.3 Environmental changes and evolutionary changes 50 3.3.1 Extreme evolutionary changes 51 3.3.2 Ongoing evolutionary changes 53 3.3.3 Changes in the cultural environment 56 3.4 Ongoing human evolution 61 3.4.1 Behavioural evolution 61 3.4.2 The future of genetic engineering 63 3.4.3 The evolution of other species, including those on which we depend 64 3.5 Future evolutionary directions 65 3.5.1 Drastic and rapid climate change without changes in human behaviour 66 3.5.2 Drastic but slower environmental change accompanied by changes in human behaviour 66 3.5.3 Colonization of new environments by our species 67 Suggestions for further reading 68 References 69 4 Millennial tendencies in responses to apocalyptic threats 73 James J. -

Human Genetic Enhancements: a Transhumanist Perspective

Human Genetic Enhancements: A Transhumanist Perspective NICK BOSTROM Oxford University, Faculty of Philosophy, 10 Merton Street, Oxford, OX1 4JJ, U. K. [Preprint of paper published in the Journal of Value Inquiry, 2003, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 493-506] 1. What is Transhumanism? Transhumanism is a loosely defined movement that has developed gradually over the past two decades. It promotes an interdisciplinary approach to understanding and evaluating the opportunities for enhancing the human condition and the human organism opened up by the advancement of technology. Attention is given to both present technologies, like genetic engineering and information technology, and anticipated future ones, such as molecular nanotechnology and artificial intelligence.1 The enhancement options being discussed include radical extension of human health-span, eradication of disease, elimination of unnecessary suffering, and augmentation of human intellectual, physical, and emotional capacities.2 Other transhumanist themes include space colonization and the possibility of creating superintelligent machines, along with other potential developments that could profoundly alter the human condition. The ambit is not limited to gadgets and medicine, but encompasses also economic, social, institutional designs, cultural development, and psychological skills and techniques. Transhumanists view human nature as a work-in-progress, a half-baked beginning that we can learn to remold in desirable ways. Current humanity need not be the endpoint 1 of evolution. Transhumanists -

![F.3. the NEW POLITICS of ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE [Preliminary Notes]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6619/f-3-the-new-politics-of-artificial-intelligence-preliminary-notes-1566619.webp)

F.3. the NEW POLITICS of ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE [Preliminary Notes]

F.3. THE NEW POLITICS OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE [preliminary notes] MAIN MEMO pp 3-14 I. Introduction II. The Infrastructure: 13 key AI organizations III. Timeline: 2005-present IV. Key Leadership V. Open Letters VI. Media Coverage VII. Interests and Strategies VIII. Books and Other Media IX. Public Opinion X. Funders and Funding of AI Advocacy XI. The AI Advocacy Movement and the Techno-Eugenics Movement XII. The Socio-Cultural-Psychological Dimension XIII. Push-Back on the Feasibility of AI+ Superintelligence XIV. Provisional Concluding Comments ATTACHMENTS pp 15-78 ADDENDA pp 79-85 APPENDICES [not included in this pdf] ENDNOTES pp 86-88 REFERENCES pp 89-92 Richard Hayes July 2018 DRAFT: NOT FOR CIRCULATION OR CITATION F.3-1 ATTACHMENTS A. Definitions, usage, brief history and comments. B. Capsule information on the 13 key AI organizations. C. Concerns raised by key sets of the 13 AI organizations. D. Current development of AI by the mainstream tech industry E. Op-Ed: Transcending Complacency on Superintelligent Machines - 19 Apr 2014. F. Agenda for the invitational “Beneficial AI” conference - San Juan, Puerto Rico, Jan 2-5, 2015. G. An Open Letter on Maximizing the Societal Benefits of AI – 11 Jan 2015. H. Partnership on Artificial Intelligence to Benefit People and Society (PAI) – roster of partners. I. Influential mainstream policy-oriented initiatives on AI: Stanford (2016); White House (2016); AI NOW (2017). J. Agenda for the “Beneficial AI 2017” conference, Asilomar, CA, Jan 2-8, 2017. K. Participants at the 2015 and 2017 AI strategy conferences in Puerto Rico and Asilomar. L. Notes on participants at the Asilomar “Beneficial AI 2017” meeting. -

Philos 121: January 24, 2019 Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky, “The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence” (Skip Pp

Philos 121: January 24, 2019 Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky, “The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence” (skip pp. 7–13) Jeremy Bentham, Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Ch. I–II Suppose we tell AI: “Make paper clips.” Unfortunately, AI has become advanced enough to design ever more intelligent AI, which in turn designs ever more intelligent AI, and so on. AI then tries to turn the universe into a paper-clip making factory, diverting all resources from food production into paper-clip production. Getting hungry, we try to turn it off. AI interprets us and our attempts to turn it off as obstacles to making paper clips. So it eliminates the obstacles… So… what should we tell AI to do, if we have only one chance to get it right? This is very close to the basic question of moral philosophy: In the most basic and general terms, what should we, or any other intelligent agent, do? The road to utilitarianism: First premise (Hedonism): What is good for us as an end is pleasure, and what is bad for us as an end is pain. Good as a means vs. good as an end: • Good as a means: good because it helps to bring about something else that is good. • But this chain of means has to end somewhere. There has to be something that is: • Good as an end: good because of what it is in itself and not because of what it brings about. What is good for us as an end? The answer at the end of every chain seems to be: pleasure and the absence of pain. -

Intergalactic Spreading of Intelligent Life and Sharpening the Fermi Paradox

Eternity in six hours: intergalactic spreading of intelligent life and sharpening the Fermi paradox Stuart Armstronga,∗, Anders Sandberga aFuture of Humanity Institute, Philosophy Department, Oxford University, Suite 8, Littlegate House 16/17 St. Ebbe's Street, Oxford, OX1 1PT UK Abstract The Fermi paradox is the discrepancy between the strong likelihood of alien intelligent life emerging (under a wide variety of assumptions), and the ab- sence of any visible evidence for such emergence. In this paper, we extend the Fermi paradox to not only life in this galaxy, but to other galaxies as well. We do this by demonstrating that traveling between galaxies { indeed even launching a colonisation project for the entire reachable universe { is a rela- tively simple task for a star-spanning civilization, requiring modest amounts of energy and resources. We start by demonstrating that humanity itself could likely accomplish such a colonisation project in the foreseeable future, should we want to, and then demonstrate that there are millions of galaxies that could have reached us by now, using similar methods. This results in a considerable sharpening of the Fermi paradox. Keywords: Fermi paradox, interstellar travel, intergalactic travel, Dyson shell, SETI, exploratory engineering 1. Introduction 1.1. The classical Fermi paradox The Fermi paradox, or more properly the Fermi question, consists of the apparent discrepancy between assigning a non-negligible probability for intelligent life emerging, the size and age of the universe, the relative rapidity ∗Corresponding author Email addresses: [email protected] (Stuart Armstrong), [email protected] (Anders Sandberg) Preprint submitted to Acta Astronautica March 12, 2013 with which intelligent life could expand across space or otherwise make itself visible, and the lack of observations of any alien intelligence. -

Transhumanism

T ranshumanism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=T ranshum... Transhumanism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia See also: Outline of transhumanism Transhumanism is an international Part of Ideology series on intellectual and cultural movement supporting Transhumanism the use of science and technology to improve human mental and physical characteristics Ideologies and capacities. The movement regards aspects Abolitionism of the human condition, such as disability, Democratic transhumanism suffering, disease, aging, and involuntary Extropianism death as unnecessary and undesirable. Immortalism Transhumanists look to biotechnologies and Libertarian transhumanism other emerging technologies for these Postgenderism purposes. Dangers, as well as benefits, are Singularitarianism also of concern to the transhumanist Technogaianism [1] movement. Related articles The term "transhumanism" is symbolized by Transhumanism in fiction H+ or h+ and is often used as a synonym for Transhumanist art "human enhancement".[2] Although the first known use of the term dates from 1957, the Organizations contemporary meaning is a product of the 1980s when futurists in the United States Applied Foresight Network Alcor Life Extension Foundation began to organize what has since grown into American Cryonics Society the transhumanist movement. Transhumanist Cryonics Institute thinkers predict that human beings may Foresight Institute eventually be able to transform themselves Humanity+ into beings with such greatly expanded Immortality Institute abilities as to merit the label "posthuman".[1] Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence Transhumanism is therefore sometimes Transhumanism Portal · referred to as "posthumanism" or a form of transformational activism influenced by posthumanist ideals.[3] The transhumanist vision of a transformed future humanity has attracted many supporters and detractors from a wide range of perspectives. -

Existential Risk Prevention As Global Priority

Global Policy Volume 4 . Issue 1 . February 2013 15 Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority Nick Bostrom Research Article University of Oxford Abstract Existential risks are those that threaten the entire future of humanity. Many theories of value imply that even relatively small reductions in net existential risk have enormous expected value. Despite their importance, issues surrounding human-extinction risks and related hazards remain poorly understood. In this article, I clarify the concept of existential risk and develop an improved classification scheme. I discuss the relation between existential risks and basic issues in axiology, and show how existential risk reduction (via the maxipok rule) can serve as a strongly action-guiding principle for utilitarian concerns. I also show how the notion of existential risk suggests a new way of thinking about the ideal of sustainability. Policy Implications • Existential risk is a concept that can focus long-term global efforts and sustainability concerns. • The biggest existential risks are anthropogenic and related to potential future technologies. • A moral case can be made that existential risk reduction is strictly more important than any other global public good. • Sustainability should be reconceptualised in dynamic terms, as aiming for a sustainable trajectory rather than a sus- tainable state. • Some small existential risks can be mitigated today directly (e.g. asteroids) or indirectly (by building resilience and reserves to increase survivability in a range of extreme scenarios) but it is more important to build capacity to improve humanity’s ability to deal with the larger existential risks that will arise later in this century. This will require collective wisdom, technology foresight, and the ability when necessary to mobilise a strong global coordi- nated response to anticipated existential risks.