Eccentric First-Year Molt Patterns in Certain Tyrannid Flycatchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October–December 2014 Vermilion Flycatcher Tucson Audubon 3 the Sky Island Habitat

THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG VermFLYCATCHERilion October–December 2014 | Volume 59, Number 4 Adaptation Stormy Weather ● Urban Oases ● Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl What’s in a Name: Crissal Thrasher ● What Do Owls Need for Habitat ● Tucson Meet Your Birds Features THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG 12 What’s in a Name: Crissal Thrasher 13 What Do Owls Need for Habitat? VermFLYCATCHERilion 14 Stormy Weather October–December 2014 | Volume 59, Number 4 16 Urban Oases: Battleground for the Tucson Audubon Society is dedicated to improving the Birds quality of the environment by providing environmental 18 The Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy- leadership, information, and programs for education, conservation, and recreation. Tucson Audubon is Owl—A Prime Candidate for Climate a non-profit volunteer organization of people with a Adaptation common interest in birding and natural history. Tucson 19 Tucson Meet Your Birds Audubon maintains offices, a library, nature centers, and nature shops, the proceeds of which benefit all of its programs. Departments Tucson Audubon Society 4 Events and Classes 300 E. University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705 629-0510 (voice) or 623-3476 (fax) 5 Events Calendar Adaptation All phone numbers are area code 520 unless otherwise stated. 6 Living with Nature Lecture Series Stormy Weather ● Urban Oases ● Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl tucsonaudubon.org What’s in a Name: Crissal Thrasher ● What Do Owls Need for Habitat ● Tucson Meet Your Birds 7 News Roundup Board Officers & Directors President—Cynthia Pruett Secretary—Ruth Russell 20 Conservation and Education News FRONT COVER: Western Screech-Owl by Vice President—Bob Hernbrode Treasurer—Richard Carlson 24 Birding Travel from Our Business Partners Guy Schmickle. -

Vermilion Flycatcher

THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG VermFLYCATCHERilion July–September 2014 | Volume 59, Number 3 Birding Economics Patagonia’s Ecotourism ● Tucson Bird & Wildlife Festival What’s in a Name: Vermilion Flycatcher ● Southeastern Arizona’s Summer Sparrows Features THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG 12 What’s in a Name: Vermilion Flycatcher VermFLYCATCHERilion 13 Southeastern Arizona’s Summer July–September 2014 | Volume 59, Number 3 Sparrows 14 Hold That Note Tucson Audubon promotes the protection and stewardship of southern Arizona’s biological diversity 15 Another Important Step in Patagonia’s through the study and enjoyment of birds and the Ecotourism Efforts places they live. Founded in 1949, Tucson Audubon is southern Arizona’s leading non-profit engaging people 16 It’s the Fourth! in the conservation of birds and their habitats. 17 The Grass is Always Greener in Southeastern Arizona? Tucson Audubon Society 300 E. University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705 629-0510 (voice) or 623-3476 (fax) Departments All phone numbers are area code 520 unless otherwise stated. tucsonaudubon.org 4 Events and Classes Birding Economics 5 Events Calendar Tucson Bird & Wildlife Festival ● Patagonia’s Ecotourism Board Officers & Directors SEAZ’s Summer Sparrows ● What’s in a Name: Vermilion Flycatcher President Cynthia Pruett 5 Living with Nature Lecture Series Vice President Bob Hernbrode Secretary Ruth Russell 6 News Roundup FRONT COVER: Sulphur-bellied Flycatcher in Ramsey Treasurer Richard Carlson 18 Conservation and Education News Directors at Large Matt Bailey, Ardeth Barnhart, Canyon by Muriel Neddermeyer. Muriel is a marketing Gavin Bieber, Les Corey, Edward Curley, Jennie Duberstein, 24 Birding Travel from Our Business Partners professional and mother of two teenagers. -

Biological Resources and Management

Vermilion flycatcher The upper Muddy River is considered one of the Mojave’s most important Common buckeye on sunflower areas of biodiversity and regionally Coyote (Canis latrans) Damselfly (Enallagma sp.) (Junonia coenia on Helianthus annuus) important ecological but threatened riparian landscapes (Provencher et al. 2005). Not only does the Warm Springs Natural Area encompass the majority of Muddy River tributaries it is also the largest single tract of land in the upper Muddy River set aside for the benefit of native species in perpetuity. The prominence of water in an otherwise barren Mojave landscape provides an oasis for regional wildlife. A high bird diversity is attributed to an abundance of riparian and floodplain trees and shrubs. Contributions to plant diversity come from the Mojave Old World swallowtail (Papilio machaon) Desertsnow (Linanthus demissus) Lobe-leaved Phacelia (Phacelia crenulata) Cryptantha (Cryptantha sp.) vegetation that occur on the toe slopes of the Arrow Canyon Range from the west and the plant species occupying the floodplain where they are supported by a high water table. Several marshes and wet meadows add to the diversity of plants and animals. The thermal springs and tributaries host an abundance of aquatic species, many of which are endemic. The WSNA provides a haven for the abundant wildlife that resides permanently or seasonally and provides a significant level of protection for imperiled species. Tarantula (Aphonopelma spp.) Beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris) Pacific tree frog (Pseudacris regilla) -

Life History Account for Vermilion Flycatcher

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group VERMILION FLYCATCHER Pyrocephalus rubinus Family: TYRANNIDAE Order: PASSERIFORMES Class: AVES B324 Written by: D. Gaines Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Program Staff, August 2005 and August 2008 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY A rare, local, yearlong resident along the Colorado River, especially in vicinity of Blythe, Riverside Co. Nesters inhabit cottonwood, willow, mesquite, and other vegetation in desert riparian habitat adjacent to irrigated fields, irrigation ditches, pastures and other open, mesic areas in isolated patches throughout central southern California. Numbers have declined drastically in the Imperial and Coachella valleys and along the Colorado River, primarily because of loss of habitat (Grinnell and Miller 1944, Gaines 1977c, Remsen 1978, Garrett and Dunn 1981). Despite local extirpations in the Coachella and Imperial valleys, the overall breeding range has expanded in recent years to the north and west (Myers 2008). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Sallies for flying insects, especially bees, from exposed perches on outer portions of low trees, shrubs, and tall herb stalks, or picks insects from ground. Frequently feeds just above water surface. Regurgitates pellets (Bent 1942). Cover: Trees and large shrubs afford nesting and roosting sites, and other cover. Reproduction: Nest a compact, open cup of twigs, fine grasses, rootlets, bound with spider silk. Built in the fork of a horizontal branch in willow, cottonwood, mesquite, or other large tree or shrub. Nest height generally 2.5 to 6.2 m (8-20 ft), rarely to 15.5 m (50 ft) above ground (Bent 1942, Tinkham 1949). -

First Occurrence of Vermilion Flycatcher, Pyrocephalus Rubinus

Vol.1950 67]] GeneralNotes 517 his attempt to escapefrom the greenhouse. The bird was sent to Stanley G. Jewett of Portland, Oregon, who verified my identification. The Black-thinnedHummingbird is includedon the Oregonbird list on the basis of only two female specimens--this being the first male taken in the state.--B•R•oN M. BAILI•Y, Enterprise, Oregon. The Race of Kingfisher, Atcedo a. pattasii, Occurring in the Crimea and Ukraine, South Russia.--Peters (Check-listBirds of World, 5: 172, 1945) places Alcedoatthis suschkini Pusahoy (Bull. Soc. Nat. Moscou,Sect. Biol., 42: 15, 1933), from Crimea and Ukrainia, as a synonym of Alcedoatthis atthis (Linn6), ('Systema Naturae,' ed. I0, I: 109, 1758) from Egypt. I have recently examined in the collection of the British Museum (Nat. Hist.) examplesfrom the Crimea. I find that Crimean Kingfishersdiffer from Mediter- ranean A. a. atthis and western continental A. a. ispida Linn• by their paler ventral surfacesand smallerproportions, and particularly in the shorterbill. On comparison with material from the Caspian Basin and Persia (A. a. pallasii Reichenbach),the Crimean specimenswere found to correspondin all essentialdetails, and I consider Pusanov'srace A. a. suschkinito be a synonym of Alcedoatthis pallasii Reichenbach, (Handb. spec. Orn., 1851: 3) from Siberia, which must now be listed as ranging considerably farther to the west than hitherto recorded, that is to the Crimea and Ukraine.--P. A. C•,t•c•¾, 9, Craig Road, Cathcart,Glasgow, S. 4, Scotland. Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Muscivoraforficata, Feeding at Night.--In front of a hotel in Dublin, Erath County, Texas, during the evening of August 1, 1949, I noticed what I took to be a large bat fluttering around a streetlight. -

VERMILION FLYCATCHER (Pyrocephalus Rubinus) Stephen J

II SPECIES ACCOUNTS Andy Birch PDF of Vermilion Flycatcher account from: Shuford, W. D., and Gardali, T., editors. 2008. California Bird Species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, California, and California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento. Studies of Western Birds No. 1 VERMILION FLYCATCHER (Pyrocephalus rubinus) Stephen J. Myers Criteria Scores Population Trend 10 Range Trend 10 Population Size 10 Range Size 10 Endemism 0 Population Concentration 5 Threats 5 Current Breeding Range Historic Breeding Range County Boundaries Water Bodies Kilometers 80 40 0 80 Current and historic (ca. 1944) breeding range of the Vermilion Flycatcher in California; occurs more widely dur- ing migration and winter. Breeding numbers have declined on the whole at least moderately, reflecting changes in the core of the range along the lower Colorado River. Still, despite extirpations locally in the Coachella and Imperial valleys, the overall breeding range has expanded to the north and west. 266 Studies of Western Birds 1:266–270, 2008 Species Accounts California Bird Species of Special Concern SPECIAL CONCERN PRIORITY “particularly numerous” in the Coachella Valley (reviewed in Patten et al. 2003; e.g., “over a dozen Currently considered a Bird Species of Special within a few hours on several occasions,” Hanna Concern (breeding), priority 2. Included on prior 1935). special concern lists (Remsen 1978, highest prior- ity; CDFG 1992). RECENT RANGE AND ABUNDANCE BREEDING BIRD SURVEY STATISTICS IN CALIFORNIA FOR CALIFORNIA Since the 1940s, the Vermilion Flycatcher has Data inadequate for trend assessment (Sauer et declined as a breeding bird in California despite al. -

Birding and Natural History in Southeast Arizona May 12

Birding and Natural History in Southeast Arizona Mark Pretti Nature Tours, L.L.C. and the Golden Gate Audubon Society May 12 - 18, 2022 Southeast Arizona is one of the most biologically diverse areas in the United States. Habitats include the Sonoran Desert with its dramatic columnar cacti, the Chihuahuan desert with its grasslands and desert scrub, and the dramatic “Sky Islands” where species from the Rocky Mountains and Mexico’s Sierra Madre come together. During our journey, we’ll explore most of these habitats, encounter a great diversity of plants and animals, and enjoy fine weather at one of the richest times of year. We’ll visit many of the birding and wildlife hotspots – Madera Canyon, the Patagonia area, Huachuca Canyon, and the San Pedro River. Species we’re likely to see include elegant trogon, gray hawk, zone-tailed hawk, vermilion flycatcher, painted redstart, Grace’s, Lucy’s, red- faced and other warblers, three species of Myiarchus flycatcher (ash-throated, brown- crested, and dusky-capped), thick-billed kingbird, northern beardless tyrannulet, greater pewee, yellow-eyed junco, up to seven species of hummingbirds, many sparrows (five- striped, Botteri’s, rufous-winged, black-throated, rufous-crowned), Scott’s oriole, and many others. In addition to birds, the area is well known for its butterfly diversity, with the Huachuca Mountains alone harboring almost one-quarter of all the butterflies found in the U.S. While May is not the peak season for butterflies, we should see as many as 15 - 20 species. Mammal diversity in the area is also high, and we've seen 20 species on past trips - these include round-tailed ground-squirrel, Arizona gray squirrel, Coues' white-tailed deer, pronghorn, black-tailed jackrabbit, coyote, bobcat, coatimundi, and javelina. -

Vermilion Flycatcher Pyrocephalus Rubinus and Tropical Pewee Contopus Cinereus from Paraguay

COMUNICAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA Striking plumage anomalies in two Tyrannidae (Passeriformes): Vermilion Flycatcher Pyrocephalus rubinus and Tropical Pewee Contopus cinereus from Paraguay Paul Smith1 1FAUNA Paraguay, Carmen de Lara Castro 422, Encarnación, Paraguay, Reserva Natural Laguna Blanca, Municipalidad de Santa Rosa del Aguaray, Paraguay. E-mail: [email protected] RESUMO. A primeira documentação de anomalias da plumagem em Tyrannidae do Paraguai é apresentada; melanismo em Contopus cinereus e xantocromia em Pyrocephalus rubinus. Palavras-chave: melanismo; xantocromiaere Plumage anomalies may be caused by differing unaware of any previously documented plumage abnormalities amounts and distributions of pigments usually present in in this species. feathers, chemical changes to pigments resulting in abnormal colors or changes in feather structure (HARRISON 1985) or genetic, Vermilion Flycatcher Pyrocephalus rubinus environmental or dietary factors (DORST 1971, GONÇALVES (xanthochroism or flavism) JUNIOR et al. 2008). The most extreme variations of abnormal pigmentation occur in individuals that show marked reductions A xanthochroistic (flavistic) male Vermilion Flycatcher or increases in the normal pigments present (HARRISON 1985). Pyrocephalus rubinus (Fig 2) was photographed in Dry Chaco Though probably not uncommon in nature (HOSNER scrub at Fortín Toledo, Departamento Boquerón on 12 October & LEBBIN 2006, VAN GROUW 2013), individuals exhibiting 2013. The red areas of the typical plumage had been completely plumage aberrations frequently find themselves at a selective replaced by pale orange-yellow. Xanthochroism is a genetic or disadvantage and thus may be short-lived, meaning that they dietary induced condition affecting the carotenoid pigments for are rarely observed. Some aberrant individuals are more red coloration, replacing them with yellow (GÓMEZ et al. -

Birds of Cibola National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Birds of Cibola National Wildlife Refuge Cibola National Wildlife Refuge is located Common Name Sp S F W Common Name Sp S F W along the lower Colorado River 20 miles Ducks, Geese, and Swans ___*Sora C C C C south of Blythe, California. Approximately ___Fulvous Whistling-Duck X X ___*Common Moorhen C C C C two-thirds of the refuge is in Arizona and one- ___Gr. White-fronted Goose U U ___*American Coot A A A A third is in California and encompasses 18,555 ___Snow Goose C C Cranes acres. The refuge was established in 1964 to ___Ross’s Goose U U ___Sandhill Crane O C mitigate the loss of fish and wildlife habitat ___Brant X Stilts and Avocets involved in the channelization projects along ___Canada Goose O A A ___*Black-necked Stilt C U C U the Colorado River. ___Tundra Swan O O ___American Avocet U R U R The main portion of the refuge is alluvial ___Wood Duck U U Plovers river bottom with dense growths of salt cedar, ___Gadwall U C C ___Black-bellied Plover R mesquite, and arrowweed along with several ___Eurasian Wigeon O ___Snowy Plover O O R hundred acres of revegetated cottonwood ___American Wigeon U C A ___Semipalmated Plover O O and willow habitat. Through this flows the ___*Mallard C U C A ___*Killdeer A A C C Colorado River, in both a dredged channel and ___Blue-winged Teal O O Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies a portion of its original channel. -

Status and Occurrence of Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus Rubinus) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Submitted: April 15, 2018. Introduction and Distribution The Vermillion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus) is a spectacular plumaged passerine that is found from the arid deserts of the southern United States, throughout Central America, and throughout South America, including the Galapagos Islands (Fitzpatrick et al. 2004). This species breeds in Arid scrub, farmlands, parks, golf courses, desert, savannah, cultivated lands, and riparian woodland, and is usually found near water (Sutton 1967b, Oberholser 1974c).There are many recognized subspecies that could one day end up as separate species and it is recommended reading Clements et al. (2017) to find out all the various forms of this species. In this account, the focus will be on the more widespread North American subspecies. In North America, there are 2 subspecies of Vermilion Flycatcher (Clements et al. 2017). The first subspecies of Vermilion Flycatcher is (Pyrocephalus rubinus flammeus) which is a localized subspecies found in the lowlands of south-central and southeastern California (Crouch 1959). Current breeding locations in California include San Bernardino, Riverside, San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and Ventura counties, north to Kern County (Rosenberg et al. 1991, Small 1994, Myers 2008). This subspecies also breeds in southern Nevada, where it is locally common, and is generally found north to 37°N (Ellison et al. 2009), with one nesting record north near Reno (Ryser 1985). The range of the Vermilion Flycatcher extends up into the extreme southwestern corner of Utah where it is rare (Behle et al. -

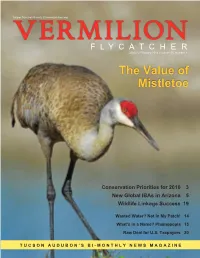

The Value of Mistletoe

Tucson Audubon Society | tucsonaudubon.org VERMILION F L YCAT CHE R January–February 2010 | Volume 55,54, Number 15 The Value of Mistletoe Conservation Priorities for 2010 3 New Global IBAs in Arizona 5 Wildlife Linkage Success 19 Wasted Water? Not in My Patch! 14 What’s in a Name? Phainopepla 15 Raw Deal for U.S. Taxpayers 20 Tucson Audubon’s bi-monTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Features Tucson Audubon Society | tucsonaudubon.org 13 Water and Wildlife VERMILION 14 Wasted Water? Not in My Patch! F L YCATCHER January–February 2010 | Volume 55,54, Number 15 15 What’s in a Name? Phainopepla The Value of 16 Discovering the Value of Mistletoe Mistletoe Tucson Audubon Society is dedicated to improving the quality of the environment by providing education, conservation, and recreation programs, Departments environmental leadership, and information. Tucson 3 Commentary Audubon is a non-profit volunteer organization of people with a common interest in birding and natural 4 News Roundup history. Tucson Audubon maintains offices, a library, 8 Events Calendar and nature shops in Tucson, the proceeds of which 8 Events and Classes benefit all of its programs. Conservation Priorities for 2010 3 12 Living With Nature New Global IBAs in Arizona 5 Tucson Audubon Society Wildlife Linkage Success 19 300 E. University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705 18 Conservation and Education News Wasted Water? Not in My Patch! 14 629-0510 (voice) or 623-3476 (fax) What’s in a Name? Phainopepla 15 All phone numbers are area code 520 unless otherwise stated. 21 Field Trips Raw Deal for U.S. -

Vermilion Flycatcher

September 2020 Vermilion Flycatcher Bird of the Month Officers by Grace Hu$man President Hal Yocum This summer, we Vice President Grace Huffman were treated to a Secretary Sharon Henthorn very special sight at Treasurer Nancy Vicars 5ongmire 5a,e6 a Parliament Vacant male Vermillion Fly- catcher! Programs Warren Harden Recorder Esther M. Key ale Vermillion Fly7 Conserva%on Ann Sherman catchers loo, li,e B Grace Huffman Field Trips Nancy Vicars 8ery mas,ed bandits, )immy Woodard with a bright red Hal Yocum head and lower body and a dar, mas,, Bob Holbroo, wings, tail, and upper Newsle.er Patricia Velte side. Females are Publicity Doug Eide much more muted Historian Vacant with lots of brown and a %nge of color Refreshments Pa1 High near the base of the tail. And they9re small6 about 5.5 inches in length. Here in the Webmaster Patricia Velte US they are primarily found in the Southwest, and they winter along the Gulf Coast. But their range extends deeply into South America. Throughout their range there The Oklahoma City Audubon society are many different subspecies, including some with more gray than red= They love the open country, and can also o>en be found in stream corridors out in the desert, is neither a chapter of nor affiliated where they will usually nest. with Naonal Audubon. A>er nes%ng, they have been ,nown to wander, which is li,ely how the one ended up at 5ongmire 5a,e near Pauls Valley, OK. He arrived in early or mid7 )uly, and stayed un%l the end of August.