THROUGH VISUAL METHODOLOGY Chapter Eighteen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

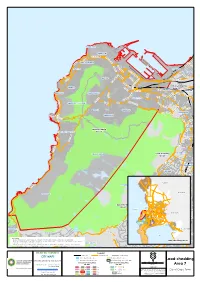

An Initial Archaeological Assessment of Bloubergstrand

AN INITIAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF BLOUBERGSTRAND (FOR STRUCTURE PLAN PURPOSES ONLY) Prepared for Steyn Larsen and Partners December 1992 Prepared by Archaeology Contracts Office Department of Archaeology University of Cape Town Rondebosch 7700 Phone (021) 650 2357 Fax (021) 650 2352 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this report has been to identify areas of archaeological sensitivity in an area of Bloubergstrand as part of a local structure plan being compiled by Steyn, Larsen and Partners, Town and Regional Planners on behalf of the Western Cape Regional Services Council. The area of land which is examined is presented in Figure 1. Our brief specifically requested that we not undertake any detailed site identification. The conclusions reached are the result of an in loco inspection of the area and reference to observations compiled by members of the Archaeological Field Club1 during a visit to the area in 1978. While these records are useful they are not comprehensive and inaccuracies may be present. 2. BACKGROUND Human occupation of the coast and exploitation of marine resources was practised for many thousands of years before the colonisation of southern Africa by Europeans. This practise continued for some time after colonisation as well. Archaeological sites along the coast are often identified by the scatters of marine shells (middens) which accumulated at various places, sometimes in caves and rockshelters, but very often out in the open. Other food remains such as bones from a variety of faunas will often accompany the shells showing that the early inhabitants utilised the full range of resources of the coastal zone. -

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

The History of Rondebosch Common a Plaque on a Stone at the South Cape Once Again

An Oa~i~ ~ A YQSt of flowQting or by Betty Dwight and Joanne Eastman, 1 ondebosch Common was declared a National Monument in 1961, thereby preserving, Runintentionally, a small piece of Cape Flats flora 'sand plain fynbos', of which so little remains, in the southern suburbs of Cape Town. Standing in the middle of the Common, surrounded by busy roads, one can still feel a sense of peace as the noise of the cars fade in the background. On closer inspection, with eyes turned to the ground, a wonderful miniature world of flowers, insects, birds and butterflies opens up. It is truly an oasis of wildness within the city. In January amongst the dry grass there are little patches of yellow Lobelia, Monopsis lutea. The African Monarch butterfly with its russet brown wings, tipped with black and white, flutters around the papery white Helichrysum flowers. Blue Aristea are flowering. This Aristea is taller with a strap-like stem compared to the Aristea africana seen in September. A few white Roella prostrata straggle along the ground. The Psoralea pinnata shrubs with their pale mauve flowers appear bravely in the dry season. Even in hot February there is something to find. The Struthiola shrublets are covered in small creamy, sometimes pale pink flowers. The restios stand out amongst the yellow grass with their green stems and dark brown flower heads. There are also many interesting seed-pods beginning to form. Grasshoppers, dragonflies and the Citrus Swallowtail butterflies are evident. In March the large black ants are on the move, very busy carrying seeds to their nests. -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing. -

The Chesterfield Brand New Development, Rondebosch

THE CHESTERFIELD BRAND NEW DEVELOPMENT, RONDEBOSCH THE NOVA GROUP PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT & CONSTRUCTION HEAD OFFICE 021 433 2580 SEA POINT 021 434 1223 dogongroup.com A visionary company with decades of experience COMPANY PARTICULARS Established by our CEO, Denise Dogon in 2002, Dogon Group Properties has proven to be a true real estate success story. The Dogon name has become synonymous with the proficient and effective marketing and selling of premium grade properties in Cape Town and particularly the sought-after Atlantic Seaboard. Dogon Group currently have offices in high profile positions in the City Bowl, Sea Point, Southern Suburbs and Gauteng. Dogon Group Properties prides itself on its unique and focused approach to marketing and sales, providing a comprehensive and tailored solution to ensure that sales occur at the optimum price within a compressed space of time. The company utilizes an evolved and distinctive sales force of highly adept and skilled sales agents who are selected for their extensive experience, professionalism and successful track records. Headed by CEO, Denise Dogon (Head of Marketing) and Managing Director Alexa Horne, Dogon Group has a dedicated in- house marketing department ensuring that focused and specialized marketing strategies are implemented. The powerful proprietary Dogon Group database combined with its eye-catching and prominent advertising, both in print and digital media, together with our visible network of sales offices support our strong performance on the Western Cape’s Atlantic Seaboard, -

A History of the Ottery School of Industries in Cape Town: Issues of Race, Welfare and Social Order in the Period 1937 to 1968

University of the Western Cape Faculty of Education A History of the Ottery School of Industries in Cape Town: Issues of Race, Welfare and Social Order in the period 1937 to 1968 By Nur-Mohammed Azeem Badroodien A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Education, University of the Western Cape March 2001 2 Abstract The primary task of this thesis is to explain the establishment of the ‘correctional institution’, the Ottery School of Industries, in Cape Town in 1948 and the programmes of rehabilitation, correctional and vocational training and residential care that the institution developed in the period until 1968. This explanation is located in the wider context of debates about welfare and penal policy in South Africa. The overall purpose is to show how modernist discourses in relation to social welfare, delinquency, and education came to South Africa and was mediated through a racial lens unique to this country. In so doing the thesis uses a broad range of material and levels of analysis from the ethnographic to the documentary and historical. The work seeks to locate itself at the intersection of the fields of education, history, welfare, penality and race in South Africa. The unique contribution of the study lies in the ways in which it engages with the nature of welfare institutions that took the form of Schools of Industries in the apartheid period. The thesis asserts that the motivation for the development of the institution under apartheid was not just the extension of crude apartheid policy, but was also inspired by welfarist and humanitarian goals. -

From Gqogqora to Liberation: the Struggle Was My Life

FROM GQOGQORA TO LIBERATION: THE STRUGGLE WAS MY LIFE The Life Journey of Zollie Malindi Edited by Theodore Combrinck & Philip Hirschsohn University of the Western Cape in association with Diana Ferrus Publishers IN THE SAME SERIES Married to the Struggle: ‘Nanna’ Liz Abrahams Tells her Life Story, edited by Yusuf Patel and Philip Hirschsohn. Published by the University of the Western Cape. Zollie Malindi defies his banning order in 1989 (Fruits of Defiance, B. Tilley & O. Schmitz 1990) First published in 2006 by University of the Western Cape Modderdam Road Bellville 7535 South Africa © 2006 Zolile (Zollie) Malindi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owner. Front and back cover illustrations by Theodore Combrinck. ISBN 0-620-36478-5 Editors: Theodore Combrinck and Philip Hirschsohn This book is available from the South African history online website: www.sahistory.org.za Printed and bound by Printwize, Bellville CONTENTS Acknowledgements Preface – Philip Hirschsohn and Theodore Combrinck Foreword – Trevor Manuel ZOLLIE MALINDI’S LIFE STORY 1 From a Village near Tsomo 2 My Struggle with Employment 3 Politics in Cape Town 4 Involvement in Unions 5 Underground Politics 6 Banned, Tortured, Jailed 7 Employment at Woolworths 8 Political Revival in the 1980s 9 Retirement and Reflections Bibliography ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to Graham Goddard, of the Robben Island Museum’s Mayibuye Archive located at the University of the Western Cape, for locating photographic and video material. -

Bosch Rugby Supporters' Club

RONDEBOSCH BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL 2018 2 22 STAFF & MANAGEMENT ACADEMIC 28 44 48 CULTURE PASTORAL SOCIETIES 56 84 114 SUMMER SPORT WINTER SPORT TOURS Editors Mr K Barnett, Ms J de Kock, Ms S Salih | Assistant Editors Mr A Ross, Ms S Verster Proof reader Ms A van Rensburg | Cover photo (aerial) Mr A Allen E1983 A huge thank you to all of the parents, pupils, staff and the Rondebosch Media Society who contributed photographs Art Ms P Newham | Advertising Ms C Giger Design Ms N Samsodien | Printer Novus Print Solutions incorporating Paarl Media and Digital Print Solutions Rondebosch Boys’ High School | Canigou Avenue, Rondebosch 7700 | Tel +27 21 686 3987 Email [email protected] | website www.rondebosch.com/high/ STAFF AND MANAGEMENT HEADMASTER’S ADDRESS Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen and boys, men of Through reflecting on her own life, Adichie shows that E18, welcome to the annual Grade 12 Speech Night. these misunderstandings and limited perspectives are Unfortunately, our Guest of Honour, Professor Mamokgethi universal. It is about what happens when complex human Phakeng, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town beings and situations are reduced to a single narrative. was unable to attend tonight’s proceedings but she has Her point is that each individual situation contains a graciously offered to speak at our valedictory. compilation of stories. If you reduce people or people’s behaviour to one story, you miss their humanity. “The This evening offers me, in addressing this audience, an single story creates stereotypes,” Adichie says, “and the opportunity to reflect on the year past and to celebrate problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but the achievements of the graduating group, the Matrics of that they are incomplete. -

University of Cape Town

Cape Town – University of Cape Town Directions to the UCT Upper Campus from the airport To reach the university from the airport, proceed on the N2 towards Cape Town and take the Muizenberg (M3) off-ramp. Continue until you reach and turn off at the Woolsack Drive / University of Cape Town off ramp. Turn right at the traffic lights on Woolsack Drive and go under the bridge and round the hairpin bend to the northern entrance of the campus (E10 on map on next page). Directions to the Upper Campus from Cape Town UCT’s Upper Campus (Groote Schuur Campus) is situated on the slopes of Devil’s Peak in the suburb of Rondebosch. To reach the upper campus from the city, drive along De Waal Drive or Eastern Boulevards, passing Groote Schuur Hospital on the way. Just past the hospital the road forks. Take the right-hand fork (M3 to Muizenberg). Just beyond Mostert’s Mill (windmill) on your left, take the Woolsack Drive / University of Cape Town turn-off. Turn right at the traffic lights on Woolsack Drive abd go under the bridge and round the hairpin bend to the northern entrance of the campus (E10 on map on next page). UCT – Upper Campus: Executive Education Course Venue Leslie Social Science Smuts Hall Entrance J-PAL Launch Dinner (Sunday, 16 January), Smuts Hall The Sunday Launch Dinner will be held at Smuts Hall on the UCT Upper Campus (E 8 on the map). From the UCT North Entrance (see map 1) continue to the visitor parking lot opposite the Visitor Centre (D 12 on the map). -

Water Services and the Cape Town Urban Water Cycle

WATER SERVICES AND THE CAPE TOWN URBAN WATER CYCLE August 2018 WATER SERVICES AND THE CAPE TOWN URBAN WATER CYCLE TABLE OF CONTENTS WATER SERVICES AND THE CAPE TOWN URBAN WATER CYCLE ...................................... 3 1. EVAPORATION ................................................................................................................ 5 2. CONDENSATION ............................................................................................................. 5 3. PRECIPITATION ............................................................................................................... 6 4. OUR CATCHMENT AREAS ............................................................................................. 7 5. CAPE TOWN’S DAMS ...................................................................................................... 9 6. WHAT IS GROUNDWATER? ......................................................................................... 17 7. SURFACE RUNOFFS ..................................................................................................... 18 8. CAPE TOWN’S WATER TREATMENT WORKS ............................................................ 19 9. CAPE TOWN’S RESERVOIRS ....................................................................................... 24 10. OUR RETICULATION SYSTEMS ................................................................................... 28 11. CONSUMERS .................................................................................................................. -

Load-Shedding Area 5

B A N L A L E E L C SO X K A N R N M I AN V D D E R EL N ON R A TO ATI A MIL ST G IN DISTRICT SIX WOODSTOCK B N EPPING INDUSTRIA 1 WOODSTOCK R W TS EPPING INDUSTRIA 1 O U EPPING INDUSTRIA 2 SM SALT RIVER N A VREDEHOEK P J H OBSERVATORY S I L T I U KALKSTEENFONTEIN P A M Load-shedding KGO SAN S L SE I N E PINELANDS T S JA T S L LER E ETT B R S E S E K Area 5 ORANJEZICHT LANGA K R Load-shedding DURBAN O City of Cape Town M Area 9 B O O MOWBRAY BONTEHEUWEL Load-shedding ES Load-shedding M D O RS H P TTLE Area 7 R Area 15 K SE Y Legend KEWTOWN K LIP FO ROSEBANK N Railways TE IN WOOL TABLE MOUNTAIN SACK Major Roads HAZENDAL BRIDGETOWN F Other Roads I SE TTL U ERS SYBRAND PARK D S S Standing Waterbodies E O WELCOME ESTATE D B SE PARK TTL O T ERS RH O N Intermittent Waterbodies ELM B A Load-shedding N I TU Biodiversity Networks KLI E PFO P NT Area 12 P EIN R Load-shedding Areas Feb 2021 I N SILVERTOWN C N I M A I E L M N S RONDEBOSCH E VANGUARD ESTATE HEIDEVELD S R A D J ATHLONE A N N N K U N CCT Load-shedding Areas Feb 2021 E LIPP ER O R S M G U P T 1 9 M S KLIPFO N A L NTEIN O E I C N RYLANDS Z 2 10 U S A D H N BELGRAVIA A 3 11 L W E D N N KRO M 4 12 U BOO M O K E R U R G B SURREY ESTATE 5 13 NEWLANDS M P O GATESVILLE I L M O L A M J C A 6 14 A N R E Y RONDEBOSCH EAST K S M M O 7 15 L Y U A O P K T A P P S R P AD 8 16 IS E D M VINEYAR O CRAWFORD HATTON E R O I R B F E M D CLAREMONT E PENLYN ESTATE TU O RF H Eskom Load-shedding Areas Feb 2021 V R A L LL E K MOUNTVIEW I B MA S M HARON Load-shedding E BELTHORN ESTATE NEWFIELDS 17 22 WYNBERG NU D O H Area 5 R 21 23 O D CH WO IC BOW H TABLE MOUNTAIN ES Eskom TE J R A supplied N TUR J F A E H MANENBERG S A D S K D ONCA TER M LL I E N U ACE CO URSE TURF HALL S B R T S U G R N I E G E R BISHOPSCOURT T H W N The load-shedding areas, as indicated E PINATI ESTATE O L on the map, is an estimation of this F R D LANSDOWNE H E O A D S Please note: customer areas.