Neurologic Complications of the Reactivation of Varicella–Zoster Virus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syphilis Staging and Treatment Syphilis Is a Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Caused by the Treponema Pallidum Bacterium

Increasing Early Syphilis Cases in Illinois – Syphilis Staging and Treatment Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by the Treponema pallidum bacterium. Syphilis can be separated into four different stages: primary, secondary, early latent, and late latent. Ocular and neurologic involvement may occur during any stage of syphilis. During the incubation period (time from exposure to clinical onset) there are no signs or symptoms of syphilis, and the individual is not infectious. Incubation can last from 10 to 90 days with an average incubation period of 21 days. During this period, the serologic testing for syphilis will be non-reactive but known contacts to early syphilis (that have been exposed within the past 90 days) should be preventatively treated. Syphilis Stages Primary 710 (CDC DX Code) Patient is most infectious Chancre (sore) must be present. It is usually marked by the appearance of a single sore, but multiple sores are common. Chancre appears at the spot where syphilis entered the body and is usually firm, round, small, and painless. The chancre lasts three to six weeks and will heal without treatment. Without medical attention the infection progresses to the secondary stage. Secondary 720 Patient is infectious This stage typically begins with a skin rash and mucous membrane lesions. The rash may manifest as rough, red, or reddish brown spots on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and/or torso and extremities. The rash does usually does not cause itching. Rashes associated with secondary syphilis can appear as the chancre is healing or several weeks after the chancre has healed. -

Understanding Vasculitis Factsheet

Vasculitis - The Facts This factsheet is intended as a simple There is no cure for PSV, but it can usually be introduction to vasculitis for those who have just controlled by use of steroids, chemotherapy and been diagnosed with vasculitis, members of their immune suppressing drugs. Long term drug therapy is family, friends, work colleagues and for others often required. If all goes well some patients go into who may want to know about the disease. “full remission” - ie they no longer need drugs. But relapse is common. What is Vasculitis Vasculitis is a rare inflammatory disease which affects People suffering from vasculitis often experience about 2-3000 new people each year in the UK. muscle weakness and chronic fatigue. Some Vasculitis means inflammation of the blood vessels. experience chronic pain due to nerve damage or Any vessels in any part of the body can be affected. severe migraines and headaches due to damaged blood vessels in the head. There are several different types of vasculitis. In the first type, the acute form, it can be caused by Others require dialysis or kidney transplants. Many infections, reaction to drugs or exposure to chemicals. have breathing problems and others are left with Often the problem is localised, such as a rash. In these permanent physical disabilities. cases the disease usually needs no treatment. Other types of vasculitis can be secondary to (or as a The most “common” types of these rare consequence of) other illnesses such as rheumatoid vasculitis diseases are: arthritis or some types of cancer. ° Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA) (previously known as Wegener’s Granulomatosis) The third group is known as Primary Systemic ° Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) Vasculitis (PSV). -

Comorbidities in Psoriasis: the Recognition of Psoriasis As a Systemic Disease and Current Management

Review Derleme 71 DOI: 10.4274/turkderm.09476 Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereology 2017;51:71-7 Comorbidities in psoriasis: The recognition of psoriasis as a systemic disease and current management Psoriazisde komorbiditeler: Psoriazisin sistemik hastalık olarak kabul edilmesi ve güncel yaklaşım Göknur Kalkan Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Dermatology, Ankara, Turkey Abstract Psoriasis, with a worldwide prevalence of 2-3%, is now assumed as a systemic chronic inflammatory disease accompanied by comorbidities while it was accepted as a disease limited only to the skin in the past. There are several classifications of the comorbidities which are more common in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Simply, comorbidities can be classified as classic, emerging, related to lifestyle, related to treatment. They can also be categorized as medical comorbidities, psychiatric/psychologic comorbidities, and behaviors contributing to medical and psychiatric comorbidities. In this review, providing early diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities, learning screening recommendations for early detection and long-term disease control and improvement in life quality by integrated, multidisciplinary approach were targeted. Keywords: Psoriasis, comorbidity, systemic disease Öz Tüm dünyada %2-3 oranında görülme sıklığına sahip psoriazis, geçmişte sadece deriye sınırlı kabul edilirken, günümüzde birçok komorbiditenin eşlik ettiği kronik sistemik enflamatuvar bir hastalık olarak ele alınmaktadır. Orta-şiddetli düzeyde -

Successful Treatment with Rituximab in a Patient with TTP Secondary to Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

□ CASE REPORT □ Successful Treatment with Rituximab in a Patient with TTP Secondary to Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Yukari Asamiya 1, Takahito Moriyama 1, Mari Takano 1, Chihiro Iwasaki 1, Kazuo Kimura 1, Yukako Ando 1, Akiko Aoki 1, Kan Kikuchi 2, Takashi Takei 1, Keiko Uchida 1 and Kosaku Nitta 1 Abstract We report a case of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) secondary to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis treated by rituximab. TTP secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis is very rare and has a high mortality rate. We employed rituximab and successfully treated TTP secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis, because standard therapies, such as steroid therapy, intravenous pulse cyclophos- phamide, and repeated plasma exchange (PE), did not suppress her disease activity. This is the first report to suggest that rituximab can achieve complete remission of TTP secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis. Key words: ANCA-associated vasculitis, TTP, rituximab, renal failure, intrapulmonary hemorrhage, hemo- dialysis (Inter Med 49: 1587-1591, 2010) (DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3135) pies such as steroids and therapeutic PE (4-6). However, ri- Introduction tuximab was employed mainly against idiopathic TTP, and there were few reports discussing treatment of secondary Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated TTP; in particular, TTP with ANCA-associated vasculitis vasculitis is recognized as a multisystem autoimmune dis- was rare. Here, we report a patient with TTP secondary to ease characterized by ANCA production and small vessel in- myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (MPO- flammation (1). It’s typical clinical manifestations are rap- ANCA) associated vasculitis who was treated using rituxi- idly progressive glomerulonephritis and the occasional de- mab combined with steroid pulse, IVCY and repeated PE. -

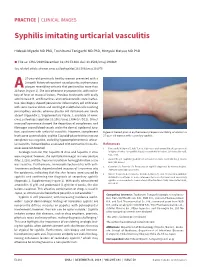

Syphilis Imitating Urticarial Vasculitis

PRACTICE | CLINICAL IMAGES Syphilis imitating urticarial vasculitis Hideaki Miyachi MD PhD, Toshibumi Taniguchi MD PhD, Hiroyuki Matsue MD PhD n Cite as: CMAJ 2019 December 16;191:E1384. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190469 See related article at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.191075 27-year-old previously healthy woman presented with a 2-month history of recurrent raised pruritic erythematous plaques resembling urticaria that persisted for more than 24A hours (Figure 1). She was otherwise asymptomatic, with no his- tory of fever or mucosal lesions. Previous treatments with orally administered H1 antihistamines and corticosteroids were ineffec- tive. Skin biopsy showed perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration with some nuclear debris and swelling of endothelial cells involving postcapillary venules, whereas plasma cell infiltration was nearly absent (Appendix 1, Supplementary Figure 1, available at www. cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190469/-/DC1). Direct immunofluorescence showed the deposition of complement and fibrinogen around blood vessels and in the dermal–epidermal junc- tion, consistent with urticarial vasculitis. However, complement Figure 1: Raised pruritic erythematous plaques resembling urticaria in a levels were unremarkable, and the C1q solid-phase test for immune 27-year-old woman with secondary syphilis. complexes was negative, excluding hypocomplementemic urticar- ial vasculitis. Autoantibodies associated with connective tissue dis- References eases were not detected. 1. Tanizaki R, Nichijima T, Aoki T, et al. High-dose oral amoxicillin plus probenecid Serologic tests for HIV, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus is highly effective for syphillis in patients with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:177-83. were negative; however, the rapid plasma reagin test was positive (titer, 1:128), and the Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay 2. -

Cerebral Vasculitis Associated with Shingles J D M Edgar, J J Crosbie, S a Hawkins

The Ulster Medical Joumal, Volume 59, No. 1, pp. 77- 81, April 1990. Case report Cerebral vasculitis associated with shingles J D M Edgar, J J Crosbie, S A Hawkins Accepted 9 August 1989. Shingles is a common manifestation of infection with herpes zoster virus (more correctly varicella-zoster virus) in middle-aged or elderly people. We describe three patients who developed brain stem encephalitis and cerebral vasculitis due to infection with this agent during a 12-month period. CASE 1 A 77-year-old lady initially presented to her family doctor in January 1987. She complained of a painful left ear with associated hearing loss and dizziness. There were vesicles on the left pinna, and she had a left lower motor neurone facial palsy. She was treated for five days with oral acyclovir and topical idoxuridine, but her symptoms did not resolve. Two weeks after the onset she became ataxic, with double vision and nausea. She was admitted to an ear, nose and throat ward, and a neurological opinion was sought. She was fully alert and orientated. There were vesicles on the left pinna. She had gaze -evoked nystagmus on horizontal and vertical gaze, maximum on left lateral gaze. There was a complete left lower motor neurone facial palsy. There was a right carotid artery bruit. There were no other cranial nerve lesions. Power and sensation were fully intact, tendon reflexes were symmetrical but the left plantar response was extensor. She had marked truncal ataxia and left - sided inco - ordination. Computerised tomography scan of the head showed evidence of cerebral atrophy but no focal lesion. -

Proliferative Lupus Nephritis and Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis During Treatment with Etanercept ADAM MOR, CLIFTON O

Case Report Proliferative Lupus Nephritis and Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis During Treatment with Etanercept ADAM MOR, CLIFTON O. BINGHAM III, LAURA BARISONI, EILEEN LYDON, and H. MICHAEL BELMONT ABSTRACT. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a proinflammatory cytokine. Agents that neutralize TNF-α are effective in the treatment of disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), spondyloarthropathies, and inflammatory bowel disease. TNF-α antagonist therapy has been associated with the development of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies, as well as the infrequent development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)- like disease. We describe the first case of biopsy-confirmed proliferative lupus nephritis and leuko- cytoclastic vasculitis in a patient treated with etanercept for JRA. (J Rheumatol 2005; 32:740–3) Key Indexing Terms: TUMOR NECROSIS FACTOR SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS NEPHRITIS VASCULITIS ETANERCEPT Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a proinflammatory CASE REPORT cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of several inflamma- A 22-year-old woman presented with a purpuric rash and lower extremity tory and autoimmune diseases1. Agents that neutralize TNF edema. At 14 years of age she was diagnosed with polyarticular JRA after are effective in the treatment of disorders such as rheuma- presenting with symmetric arthritis of hands, shoulders, ankles, and knees. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were elevated, toid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), spondy- while both ANA and rheumatoid factor (RF) were negative. During her dis- loarthropathies, and inflammatory bowel disease. One TNF ease course she did not experience any extraarticular manifestations. She antagonist is etanercept, a soluble type II TNF receptor was treated with multiple disease modifying antirheumatic drugs [e.g, (p75) fused to the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin (Ig) plaquenil, sulfasalazine, and methotrexate (MTX)] without achieving com- G1. -

Versus Arthritis Vasculitis Information Booklet

Condition Vasculitis Vasculitis This booklet provides information and answers to your questions about this condition. Arthritis Research UK booklets are produced and printed entirely from charitable donations. What is vasculitis? Vasculitis means inflammation of the blood vessels. There are several different types of the condition, many with unknown causes, but treatments can be very effective. In this booklet we’ll briefly explain the main types of vasculitis, how they’re diagnosed and treated, what you can do to help yourself and where to get more information. At the back of this booklet you’ll find a brief glossary of medical words – we’ve underlined these when they’re first used. www.arthritisresearchuk.org Page 2 of 32 Vasculitis information booklet Arthritis Research UK What’s inside? 2 Vasculitis at a glance 5 Who diagnoses and treats 15 What is the outlook? vasculitis? 15 How is vasculitis diagnosed? 6 What is vasculitis? – What tests are there? 8 What are the symptoms 17 What treatments are there for vasculitis? of vasculitis? – Drugs 9 What types of vasculitis 20 Self-help and daily living are there? – Exercise – Takayasu arteritis (TA) – Diet and nutrition – Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) – Stop smoking – Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) – Keep warm – Kawasaki disease 22 Research and new – Granulomatosis with polyangiitis developments (Wegener’s granulomatosis) 23 Glossary – Behçet’s syndrome – Eosinophilic granulomatosis 26 Where can I find out more? with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss 28 We’re here to help syndrome) – Microscopic polyangiitis – Cryoglobulin-associated vasculitis – Immunoglobulin A vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein purpura) 14 Who gets vasculitis? 15 What causes vasculitis? Page 3 of 32 Vasculitis information booklet At a glance Vasculitis There are several different types of vasculitis but all are treatable. -

CNS Vasculitis As a Manifestation of Systemic Sclerosis Corey E

CNS Vasculitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Sclerosis Corey E. Goldsmith, MD and Joseph S. Kass, MD Department of Neurology, Ben Taub General Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX Harris County Hospital District Neither author has anything to disclose INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT, cont DISCUSSION Systemic sclerosis (or scleroderma) is a connective tissue Figure 1. CT and MRI Brain Imaging Systemic sclerosis is a connective tissue disease of disease manifested by rapidly progressive fibrosis of the skin, unknown etiology which causes rapidly progressive fibrosis of lungs, and other internal organs usually felt to have rare the skin, lungs, and other internal organs. Currently, cranial secondary central nervous system (CNS) manifestations. We and autonomic neuropathies are widely recognized present a patient with extensive CNS involvement of systemic neurological associations with systemic sclerosis, but central sclerosis consistent with a diffuse CNS vasculitis. Recent nervous system manifestations are much rarer. This case evidence supports a more direct role of the central nervous A B C shows the most extensive involvement of the central nervous system in systemic sclerosis. system in systemic sclerosis of which we are aware with CASE REPORT serologic and imaging evidence of vasculitis. Previous literature has hypothesized that the CNS A 24 year-old right-handed woman with a two year history involvement in systemic sclerosis is due to a secondary of advanced systemic sclerosis treated with prednisone 10mg DE vasculopathy. However, there is argument for a more primary daily presented with a week-long history of progressive CT head without contrast (A) shows multiple calcifications. MRI FLAIR (B) involvement of the central nervous system. -

Vasculitis and Systemic Lupus Erythematous (SLE) Elisabetta Cortis*, Maria Greca Magnolia from 71St Congress of the Italian Society of Pediatrics

Cortis and Magnolia Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2015, 41(Suppl 2):A20 http://www.ijponline.net/content/41/S2/A20 MEETINGABSTRACT Open Access Vasculitis and Systemic Lupus Erythematous (SLE) Elisabetta Cortis*, Maria Greca Magnolia From 71st Congress of the Italian Society of Pediatrics. Joint National Meeting SIP, SIMGePeD, Study Group on Pediatric Ultrasound, SUP Study Group on Hypertension Rome, Italy. 4-6 June 2015 Vasculitis are a heterogeneous group of disorders char- Table 1. Vasculitis: classification (Adapted from EULAR/ acterized by inflammation of the blood vessels of differ- PReS endorsed criteria for the classification of childhood ent caliber and sometimes fibrinoid necrosis with vessel vasculitis) 2006; 65:936-41 wall destruction [1]. Vasculitis in large calibre vessels prevalence Vasculitis are divided into cutaneous and systemic • Takayasu arteritis forms, primary and secondary to hypertension, immuno- Vasculitis in medium caliber vessels prevalence • Nodose Polyarteritis suppression therapy, metabolic complications. The clas- • Cutaneous polyarteritis sification is based on the affected vessel size (Table 1). • Kawasaki desease They may have neurological manifestations at the onset Vasculitis in small calibre vessels A. Granulomatous and during the desease development. These are more • Wegener Granulomatosis common in systemic forms such as SLE and Nodose • Churg-Strauss syndrome Polyarteritis (PAN). B. Non granulomatous • Microscopic polyangiitis The Schonlein-Henoch purpura and Kawasaki disease, • Schönlein-Henoch syndrome the most frequent vasculitisin childhood, rarely can have • LVC isolated • neurological disorders. There are forms of mild to mod- Urticarial vasculitis ipocomplementemica Other forms erate intensity like headache, irritability, mood disorders • Behcet desease and behavioral and forms of severe as seizures and sen- • Vasculitis secondary to infection (including nodose sory disturbance up to coma. -

Vasculitis Factsheet Dr Laurence Knott Dr David Kluth

Author Peer Reviewer Vasculitis Factsheet Dr Laurence Knott Dr David Kluth This is a leaflet for people who want general information about vasculitis. Vasculitis is a medical term meaning inflammation of blood vessels. It can be primary (occurring on its own) or secondary (occurring as part of another condition). Some people with vasculitis test positive for antibodies to constituents of certain white blood cells (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or ANCA) and are said to have ANCA vasculitis. Who gets vasculitis? Vasculitis is an uncommon illness. About 20 in every 100,000 people get ANCA vasculitis every year in the UK. Vasculitis can affect all age groups. Some are mostly diseases of childhood (e.g. Kawasaki), whilst others persist throughout adult life (ANCA systemic vasculitis). Some principally affect the elderly (e.g. giant cell arteritis). What causes vasculitis? In most cases the cause is not known. Many experts think that the illness is the result of infection in people who were born with a certain genetic predisposition. Vasculitis can also be caused by illnesses which trigger inflammation in the body such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory diseases of the bowel. Medicines associated with vasculitis include certain types of antibiotics (e.g. quinolones, sulphonamides,beta-lactams), a nti-inflammatories, the contraceptive pill, some types of fluid tablets (thiazides) and flu vaccines. Rare types of cancer (paraproteinaemia, lymphoproliferative disorder) can occasionally cause vasculitis. Are there different types of vasculitis? There are many different types of vasculitis and various ways of classifying them. Vasculitis occurring in one part of the body is known as localised vasculitis. -

Systemic Manifestations of Atopic Urticaria Allen P

Systemic Manifestations of Atopic Urticaria Allen P. Kaplan, MD Medical University of South Carolina Charlestown, SC, USA June 2011 Urticaria Acute Physical Chronic Systemic Anaphylaxis Hypotension 1) Systemic Manifestation Manifestation Diarrhea 2) Systemic Disease Anaphylaxis Skin Respiratory Gastrointestinal Vascular Urticaria Stridor Vomiting Hypotension Angioedema Wheeze Pain Diarrhea A) Typically antigen-dependent, IgE dependent thru IgE receptors B) Skin involvement as early symptom is >90% C)Diagnostic consideration: Find the antigen IgE-Dependent Physical Urticaria 1) Cold Urticaria 2) Dermatographism 3) Solar Urticaria – light-inducible autoantigen 4) Cholinergic Urticaria 1,3,4 – Occasionally associated with hypotension Cold urticaria 5 Histamine release in cold urticaria Cholinergic (generalized heat) urticaria Dermatographism 9 Diagnostic Consideration 1) Cold Urticaria – Occasionally associated with cold agglutinins or Cryoglobulins 2) Physical Urticarias occur spontaneously and are not associated with systemic diseases 3) Solar Urticaria and photosensitive rashes in SLE are different Autoimmune urticaria 12 Mast cell activation by bivalent cross- linking of the high affinity IgE receptor by specific IgG autoantibody 100 80 60 40 20 0 Percentage Histamine Release Histamine Percentage No Urticaria CU-Idiopathic CU-Autoimmune Serologic Abnormalities 1) CRP is elevated compared to normal 2) IL6 levels are increased 3) Metalloproteinase 9 levels are increased 4) Prothrombin fragments 1 + 2 are increased 5) There is no fever,