Aplonis Opaca) by Brown Treesnakes (Boiga Irregularis) on Guam*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Recovery Plan for the Sihek Or Guam Micronesian Kingfisher (Halcyon Cinnamomina Cinnamomina)

DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate actions which the best available science indicates are required to recover and protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are approved and adopted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Nothing in this plan should be construed as a commitment or requirement that any Federal agency obligate or pay funds in contravention of the Anti-Deficiency Act, 31 USC 1341, or any other law or regulation. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed as approved by the Regional Director or Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. Please check for updates or revisions at the website addresses provided below before using this plan. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. -

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Coastal Resilience Assessment

COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS COASTAL RESILIENCE ASSESSMENT 20202020 Greg Dobson, Ian Johnson, Kim Rhodes UNC Asheville’s NEMAC Kristen Byler National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Bridget Lussier Lynker, on contract to NOAA Office for Coastal Management IMPORTANT INFORMATION/DISCLAIMER: This report represents a Regional Coastal Resilience Assessment that can be used to identify places on the landscape for resilience-building efforts and conservation actions through understanding coastal flood threats, the exposure of populations and infrastructure have to those threats, and the presence of suitable fish and wildlife habitat. As with all remotely sensed or publicly available data, all features should be verified with a site visit, as the locations of suitable landscapes or areas containing flood threats and community assets are approximate. The data, maps, and analysis provided should be used only as a screening-level resource to support management decisions. This report should be used strictly as a planning reference tool and not for permitting or other legal purposes. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government, or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s partners. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or its funding sources. NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DISCLAIMER: The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of NOAA or the Department of Commerce. -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

AOU Checklist of North and Middle American Birds

12/17/2014 AOU Checklist of North and Middle American Birds Home Checklists Publica tioSneasrch Meetings Membership Awards Students Resources About Contact AOU Checklist of North and Middle American Birds Browse the checklist below, or Search Legend to symbols: A accidental/casual in AOU area H recorded in AOU area only from Hawaii I introduced into AOU area N has not bred in AOU area, but occurs regularly as nonbreeding visitor † extinct * probably misplaced in the current phylogenetic listing, but data indicating proper placement are not yet available Download a complete list of all bird species in the North and Middle America Checklist, without subspecies (CSV, Excel). Please be patient as these are large! This checklist incorporates changes through the 54th supplement. View invalidated taxa class: Aves order: Tinamiformes family: Tinamidae genus: Nothocercus species: Nothocercus bonapartei (Highland Tinamou, Tinamou de Bonaparte) genus: Tinamus species: Tinamus major (Great Tinamou, Grand Tinamou) genus: Crypturellus species: Crypturellus soui (Little Tinamou, Tinamou soui) species: Crypturellus cinnamomeus (Thicket Tinamou, Tinamou cannelle) species: Crypturellus boucardi (Slatybreasted Tinamou, Tinamou de Boucard) species: Crypturellus kerriae (Choco Tinamou, Tinamou de Kerr) order: Anseriformes family: Anatidae subfamily: Dendrocygninae genus: Dendrocygna species: Dendrocygna viduata (Whitefaced WhistlingDuck, Dendrocygne veuf) species: Dendrocygna autumnalis (Blackbellied WhistlingDuck, Dendrocygne à ventre noir) species: -

Micronesian Starling – Aplonis Opaca)As

Journal of Tropical Ecology Såli (Micronesian starling – Aplonis opaca)as www.cambridge.org/tro a key seed dispersal agent across a tropical archipelago 1, 2 3 1 Research Article Henry S. Pollock * , Evan C. Fricke , Evan M. Rehm , Martin Kastner , Nicole Suckow1, Julie A. Savidge3 and Haldre S. Rogers2 Cite this article: Pollock HS, Fricke EC, Rehm EM, Kastner M, Suckow N, Savidge JA, 1School of Global Environmental Sustainability, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 80523; and Rogers HS (2020) Såli (Micronesian starling 2 – Aplonis opaca) as a key seed dispersal agent Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 50010 and 3 across a tropical archipelago. Journal of Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 Tropical Ecology 36,56–64. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/S0266467419000361 Abstract Received: 11 August 2019 Seed dispersal is an important ecological process that structures plant communities and influences Revised: 14 November 2019 ecosystem functioning. Loss of animal dispersers therefore poses a serious threat to forest Accepted: 21 November 2019 ecosystems, particularly in the tropics where zoochory predominates. A prominent example is First published online: 17 January 2020 the near-total extinction of seed dispersers on the tropical island of Guam following the accidental Keywords: introduction of the invasive brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), negatively impacting seedling Diet; ecosystem services; frugivory; Mariana recruitment and forest regeneration. We investigated frugivory by a remnant population of Såli Islands; Micronesian starling; seed dispersal (Micronesian starling – Aplonis opaca) on Guam and two other island populations (Rota, Saipan) Author for correspondence: to evaluate their ecological role as a seed disperser in the Mariana archipelago. -

Jungle Myna (Acridotheres Fuscus)

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Jungle myna Acridotheres fuscus Steve Csurhes First published 2011 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Jungle myna Photo: Used with permission, Wikimedia Commons. Invasive animal risk assessment: Jungle myna Acridotheres fuscus 2 Contents Summary 4 Introduction 5 Identity and taxonomy 5 Description and biology 5 Diet 5 Reproduction 5 Preferred habitat and climate 6 Native range and global distribution 6 Current distribution and impact in Queensland 6 History as a pest overseas 7 Use 7 Potential distribution and impact in Queensland 7 References 8 Invasive animal risk assessment: Jungle myna Acridotheres fuscus 3 Summary Acridotheres fuscus (jungle myna) is native to an extensive area of India and parts of southeast Asia. Naturalised populations exist in Singapore, Taiwan, Fiji, Western Samoa and elsewhere. In Fiji, the species occasionally causes significant damage to crops of ground nuts, with crop losses of up to 40% recorded. Within its native range (South India), it is not a well documented pest, but occasionally causes considerable (localised) damage to fruit orchards. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13 District of Columbia, Commonwealth sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, U.S. importation of migratory birds. Virgin Islands, Guam, Commonwealth (c) What species are protected as migra- of the Northern Mariana Islands, Baker tory birds? Species protected as migra- Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, tory birds are listed in two formats to Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway suit the varying needs of the user: Al- Atoll, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, phabetically in paragraph (c)(1) of this and Wake Atoll, and any other terri- section and taxonomically in para- tory or possession under the jurisdic- graph (c)(2) of this section. Taxonomy tion of the United States. and nomenclature generally follow the Whoever means the same as person. 7th edition of the American Ornitholo- Wildlife means the same as fish or gists’ Union’s Check-list of North Amer- wildlife. ican birds (1998, as amended through 2007). For species not treated by the [38 FR 22015, Aug. 15, 1973, as amended at 42 AOU Check-list, we generally follow FR 32377, June 24, 1977; 42 FR 59358, Nov. 16, Monroe and Sibley’s A World Checklist 1977; 45 FR 56673, Aug. 25, 1980; 50 FR 52889, Dec. 26, 1985; 72 FR 48445, Aug. 23, 2007] of Birds (1993). (1) Alphabetical listing. Species are § 10.13 List of Migratory Birds. listed alphabetically by common (English) group names, with the sci- (a) Legal authority for this list. The entific name of each species following Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) in the common name. -

Conservation of Breeding Colonies of the Bank Myna, Acridotheres Ginginianus (Latham 1790), in Chapai Nawabganj, Bangladesh

Univ. j. zool. Rajshahi Univ. Vol. 30, 2011 pp. 49-53 ISSN 1023-6104 http://journals.sfu.ca/bd/index.php/UJZRU © Rajshahi University Zoological Society Conservation of breeding colonies of the bank myna, Acridotheres ginginianus (Latham 1790), in Chapai Nawabganj, Bangladesh M Farid Ahsan and M Tarik Kabir Department of Zoology, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh Abstact: A study on the conservation on breeding colonies of bank myna, Acridotheres ginginianus (Latham 1790), was conducted in Chapai Nawabganj district of Bangladesh during a period from June 2007 to October 2009. The total population in the breeding colonies was estimated as 4,452. The preferable breeding habitats of bird are bank of the river, soil heap/ditches of brickfield and holes of culvert. Environmental calamities such as bank erosion and flooding, drought and rain affect the breeding colonies. Human settlement near breeding habitats, hunting, collecting eggs and nestlings by children, and use of nets to prevent nesting at bank of the river are the main human impacts on the breeding colonies. Major threats are flood, children-fun, predators and human for its meat. Conservation awareness for this species have depicted in this paper. Key words: Conservation, breeding colonies, bank myna, Acridotheres ginginianus, Chapai Nawabganj, Bangladesh. example, Grimmett et al. (1998), Inskipp et al. Introduction (1996), Sibley & Monroe (1993, 1990), Sibley & Conservation biology is the new multidisciplinary Ahlquist (1990), Ripley (1982), Husain (2003, science that -

Swiftlets and Edible Bird's Nest Industry in Asia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Pertanika Journal of Scholarly Research Reviews (PJSRR - Universiti Putra Malaysia,... PJSRR (2016) 2(1): 32-48 eISSN: 2462-2028 © Universiti Putra Malaysia Press Pertanika Journal of Scholarly Research Reviews http://www.pjsrr.upm.edu.my/ Swiftlets and Edible Bird’s Nest Industry in Asia Qi Hao, LOOI a & Abdul Rahman, OMAR a, b* aInstitute of Bioscience, bFaculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor. [email protected] Abstract – Swiftlets are small insectivorous birds which breed throughout Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Among many swiftlet species, only a few are notable to produce edible bird’s nests (EBN) from the secreted saliva during breeding seasons. The taxonomy of swiftlets remains one of the most controversial in the avian species due to the high similarity in morphological characteristics among the species. Over the last few decades, researchers have studied the taxonomy of swiftlets based on the morphological trade, behavior, and genetic traits. However, despite all the efforts, the swiftlet taxonomy remains unsolved. The EBN is one of the most expensive animal products and frequently being referred to as the “Caviar of the East”. The EBN market value varies from US$1000.00 to US$10,000.00 per kilogram depending on its grade, shape, type and origin. Hence, bird’s nest harvesting is considered a lucrative industry in many countries in Southeast Asia. However, the industry faced several challenges over the decades such as the authenticity of the EBN, the quality assurance and the depletion of swiftlet population. -

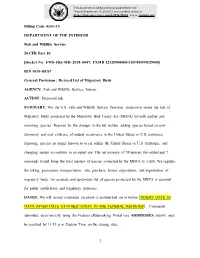

Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT of THE

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/28/2018 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2018-25634, and on govinfo.gov Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 10 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//189//FF09M29000] RIN 1018–BC67 General Provisions; Revised List of Migratory Birds AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), propose to revise the List of Migratory Birds protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by both adding and removing species. Reasons for the changes to the list include adding species based on new taxonomy and new evidence of natural occurrence in the United States or U.S. territories, removing species no longer known to occur within the United States or U.S. territories, and changing names to conform to accepted use. The net increase of 59 species (66 added and 7 removed) would bring the total number of species protected by the MBTA to 1,085. We regulate the taking, possession, transportation, sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and importation of migratory birds. An accurate and up-to-date list of species protected by the MBTA is essential for public notification and regulatory purposes. DATES: We will accept comments received or postmarked on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES, below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. -

Sturnidae Tree, Part 1

Sturnidae (Starlings) I Stripe-headed Rhabdornis, Rhabdornis mystacalis Grand Rhabdornis, Rhabdornis grandis Rhabdornithini Stripe-breasted Rhabdornis, Rhabdornis inornatus Sulawesi Myna, Basilornis celebensis ?Helmeted Myna, Basilornis galeatus ?Long-crested Myna, Basilornis corythaix Apo Myna, Goodfellowia mirandus Coleto, Sarcops calvus Graculinae White-necked Myna, Streptocitta albicollis Bare-eyed Myna, Streptocitta albertinae ?Yellow-faced Myna, Mino dumontii Long-tailed Myna, Mino kreffti Golden Myna, Mino anais Golden-crested Myna, Ampeliceps coronatus Sri Lankan Hill-Myna, Gracula ptilogenys Graculini Common Hill Myna, Gracula religiosa ?Southern Hill Myna, Gracula indica Fiery-browed Myna, Enodes erythrophris Grosbeak Starling, Scissirostrum dubium White-eyed Starling, Aplonis brunneicapillus ?Yellow-eyed Starling, Aplonis mystacea Metallic Starling, Aplonis metallica ?Long-tailed Starling, Aplonis magna Pohnpei Starling, Aplonis pelzelni ?Kosrae Starling, Aplonis corvina Micronesian Starling, Aplonis opaca Brown-winged Starling, Aplonis grandis ?Makira Starling, Aplonis dichroa Singing Starling, Aplonis cantoroides ?Tanimbar Starling, Aplonis crassa Asian Glossy Starling, Aplonis panayensis ?Moluccan Starling, Aplonis mysolensis Short-tailed Starling, Aplonis minor ?Atoll Starling, Aplonis feadensis Rennell Starling, Aplonis insularis ?Rusty-winged Starling, Aplonis zelandica ?Striated Starling, Aplonis striata ?Mountain Starling, Aplonis santovestris Polynesian Starling, Aplonis tabuensis ?Samoan Starling, Aplonis atrifusca Rarotonga Starling, Aplonis cinerascens ?Mauke Starling, Aplonis mavornata ?Tasman Starling, Aplonis fusca Sturnini Cinnyricinclini Sturninae Onychognathini Lamprotornini Sources: Lovette and Rubenstein (2007).. -

Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia Peter Pyle and John Engbring for Ornithologists Visiting Micronesia, R.P

./ /- 'Elepaio, VoL 46, No.6, December 1985. 57 Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia Peter Pyle and John Engbring For ornithologists visiting Micronesia, R.P. Owen's Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia (1977a) has proven a valuable reference for species occurrence among the widely scattered island groups. Since its publication, however, our knowledge of species distribution in Micronesia has been substantially augmented. Numerous species not recorded by Owen in Micronesia or within specific Micronesian island groups have since been reported, and the status of many other species has changed or become better known. This checklist is essentially an updated version of Owen (1977a), listing common and scientific names, and occurrence status and references for all species found in Micronesia as recorded from the island groups. Unlike Owen, who gives the status for each species only for Micronesia as a whole, we give it for -each island group. The checklist is stored on a data base program on file with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in Honolulu, and we encourage comments and new or additional information concerning its contents. A total of 224 species are included, of which 85 currently breed in Micronesia, 3 have become extinct, and 12 have been introduced. Our criteria for-species inclusion is either specimen, photograph, or adequately documented sight record by one or more observer. An additional 13 species (listed in brackets) are included as hypothetical (see below under status symbols). These are potentially occurring species for which reports exist that, in our opinion, fail to meet the above mentioned criteria.