Postnatal Evaluation and Outcome of Prenatal Hydronephrosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What a Difference a Delay Makes! CT Urogram: a Pictorial Essay

Abdominal Radiology (2019) 44:3919–3934 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02086-0 SPECIAL SECTION : UROTHELIAL DISEASE What a diference a delay makes! CT urogram: a pictorial essay Abraham Noorbakhsh1 · Lejla Aganovic1,2 · Noushin Vahdat1,2 · Soudabeh Fazeli1 · Romy Chung1 · Fiona Cassidy1,2 Published online: 18 June 2019 © This is a U.S. Government work and not under copyright protection in the US; foreign copyright protection may apply 2019 Abstract Purpose The aim of this pictorial essay is to demonstrate several cases where the diagnosis would have been difcult or impossible without the excretory phase image of CT urography. Methods A brief discussion of CT urography technique and dose reduction is followed by several cases illustrating the utility of CT urography. Results CT urography has become the primary imaging modality for evaluation of hematuria, as well as in the staging and surveillance of urinary tract malignancies. CT urography includes a non-contrast phase and contrast-enhanced nephrographic and excretory (delayed) phases. While the three phases add to the diagnostic ability of CT urography, it also adds potential patient radiation dose. Several techniques including automatic exposure control, iterative reconstruction algorithms, higher noise tolerance, and split-bolus have been successfully used to mitigate dose. The excretory phase is timed such that the excreted contrast opacifes the urinary collecting system and allows for greater detection of flling defects or other abnormali- ties. Sixteen cases illustrating the utility of excretory phase imaging are reviewed. Conclusions Excretory phase imaging of CT urography can be an essential tool for detecting and appropriately characterizing urinary tract malignancies, renal papillary and medullary abnormalities, CT radiolucent stones, congenital abnormalities, certain chronic infammatory conditions, and perinephric collections. -

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S. Tekgül, H. Riedmiller, E. Gerharz, P. Hoebeke, R. Kocvara, R. Nijman, Chr. Radmayr, R. Stein European Society for Paediatric Urology © European Association of Urology 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 Reference 6 2. PHIMOSIS 6 2.1 Background 6 2.2 Diagnosis 6 2.3 Treatment 7 2.4 References 7 3. CRYPTORCHIDISM 8 3.1 Background 8 3.2 Diagnosis 8 3.3 Treatment 9 3.3.1 Medical therapy 9 3.3.2 Surgery 9 3.4 Prognosis 9 3.5 Recommendations for crytorchidism 10 3.6 References 10 4. HYDROCELE 11 4.1 Background 11 4.2 Diagnosis 11 4.3 Treatment 11 4.4 References 11 5. ACUTE SCROTUM IN CHILDREN 12 5.1 Background 12 5.2 Diagnosis 12 5.3 Treatment 13 5.3.1 Epididymitis 13 5.3.2 Testicular torsion 13 5.3.3 Surgical treatment 13 5.4 Prognosis 13 5.4.1 Fertility 13 5.4.2 Subfertility 13 5.4.3 Androgen levels 14 5.4.4 Testicular cancer 14 5.4.5 Nitric oxide 14 5.5 Perinatal torsion 14 5.6 References 14 6. Hypospadias 17 6.1 Background 17 6.1.1 Risk factors 17 6.2 Diagnosis 18 6.3 Treatment 18 6.3.1 Age at surgery 18 6.3.2 Penile curvature 18 6.3.3 Preservation of the well-vascularised urethral plate 19 6.3.4 Re-do hypospadias repairs 19 6.3.5 Urethral reconstruction 20 6.3.6 Urine drainage and wound dressing 20 6.3.7 Outcome 20 6.4 References 21 7. -

2021 Western Medical Research Conference

Abstracts J Investig Med: first published as 10.1136/jim-2021-WRMC on 21 December 2020. Downloaded from Genetics I Purpose of Study Genomic sequencing has identified a growing number of genes associated with developmental brain disorders Concurrent session and revealed the overlapping genetic architecture of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (ID). Chil- 8:10 AM dren with ASD are often identified first by psychologists or neurologists and the extent of genetic testing or genetics refer- Friday, January 29, 2021 ral is variable. Applying clinical whole genome sequencing (cWGS) early in the diagnostic process has the potential for timely molecular diagnosis and to circumvent the diagnostic 1 PROSPECTIVE STUDY OF EPILEPSY IN NGLY1 odyssey. Here we report a pilot study of cWGS in a clinical DEFICIENCY cohort of young children with ASD. RJ Levy*, CH Frater, WB Galentine, MR Ruzhnikov. Stanford University School of Medicine, Methods Used Children with ASD and cognitive delays/ID Stanford, CA were referred by neurologists or psychologists at a regional healthcare organization. Medical records were used to classify 10.1136/jim-2021-WRMC.1 probands as 1) ASD/ID or 2) complex ASD (defined as 1 or more major malformations, abnormal head circumference, or Purpose of Study To refine the electroclinical phenotype of dysmorphic features). cWGS was performed using either epilepsy in NGLY1 deficiency via prospective clinical and elec- parent-child trio (n=16) or parent-child-affected sibling (multi- troencephalogram (EEG) findings in an international cohort. plex families; n=3). Variants were classified according to Methods Used We performed prospective phenotyping of 28 ACMG guidelines. -

Clinical Course and Effective Factors of Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Clinical Course and Effective Factors of Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux Azar Nickavar1, Niloofar Hajizadeh2, and Arash Lahouti Harahdashti3 1 Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Aliasghar Childrens’ Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2 Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Childrens’ Medical Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 3 Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Received: 5 Sep. 2013; Received in revised form: 6 Aug. 2014; Accepted: 22 Oct. 2014 Abstract- Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is one of the most important causes of urinary tract infection and renal failure in children. It is a potentially self-limited disease. The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical course and significant factors in children with primary VUR. The medical charts of 125 infants and children (27.2 % males, 72.8% females) with all grades of primary VUR were retrospectively reviewed. Mean age at diagnosis was 22.3±22.9 months. 52% of patients had bilateral VUR. Mild reflux (Grade I, II) was the most common initial grade. 53.6% of patients achieved spontaneous resolution. 30.1% of patients had decreased renal function on initial DMSA renal scan, significantly in males and severe VUR. Reflux nephropathy occurred in 17.6% of patients, especially in renal damage and male sex. No significant association was observed between recurrent urinary tract infection with the severity of VUR, and the presence of renal damage at admission. Age at diagnosis, gender, grade, laterality, the absence of recurrent urinary tract infection and renal damage had a significant correlation between spontaneous VUR resolution. -

Urinary Incontinence in Adulthood in a Course of Ectopic Ureter—Description of Two Clinical Cases with Review of Literature

Case Report Urinary Incontinence in Adulthood in a Course of Ectopic Ureter—Description of Two Clinical Cases with Review of Literature Iga Kuliniec 1,International*, Przemysław Journal of Mitura 1, Paweł Płaza 1, Damian Widz 1, Damian Sudoł 1, Michał Godzisz 1, Environmental Research2 2 3 1 Aleksandra Kołodyńskaand Public Health , Marta Monist , Agata Wisz and Krzysztof Bar Case Report 1 Department of Urology and Oncological Urology, Medical University of Lublin, Jaczewskiego 8, Urinary Incontinence20-954 inLublin, Adulthood Poland; [email protected] in a Course (P.M.); [email protected] of Ectopic (P.P.); Ureter—[email protected] of Two Clinical (D.W.); Cases [email protected] with (D.S.); [email protected] (M.G.); Review of [email protected] (K.B.) 2 2nd Department of Gynecology, Medical University of Lublin, Jaczewskiego 8, 20-954 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (M.M.) Iga Kuliniec 1,* , Przemysław Mitura 1 , Paweł Płaza 1, Damian Widz 1 , Damian Sudoł 1, Michał Godzisz 1, 3 Aleksandra Kołody ´nska 2 , Marta Department Monist 2, Agata of Diagnostic Wisz 3 and Imaging, Krzysztof Radiology Bar 1 and Nuclear Medicine, Faculty of Medical Science in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Medyków 16, 40-752 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] 1* DepartmentCorrespondence: of Urology and [email protected] Oncological Urology, Medical University of Lublin, Jaczewskiego 8, 20-954 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (M.G.); Abstract:[email protected] Urinary (K.B.)tract pathologies are the most common congenital abnormalities. -

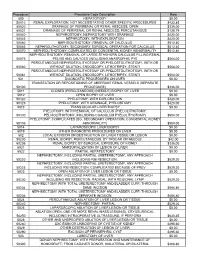

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Duplicated Collecting System-Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects

JURNALUL PEDIATRULUI – Year XVI, Vol. XVI, Nr. 64, october-december 2013 DUPLICATED COLLECTING SYSTEM-DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC ASPECTS Daescu Camelia 1,2, Portaru Laura2, Marginean Otilia 1,2, Militaru Andrea1,2, Popoiu Calin3,4, Vasilie Doru3,4, David Vlad3,4, Marcovici Tamara 1,2, Craciun Adrian1,2, Chiru Daniela1,2, Brad Giorgiana 1,2, Olariu Laura1,2, Pavel Adina2, Pantea Ioana2 Abstract ureter (a partial duplication) or, in the case of a Objectives: We present the clinical and imaging complete duplication, with 2 ureters (double ureters) exploration of four patients that have duplicated collecting that drain separately into the urinary bladder. system emphasizing the diagnostic and therapeutic features. Bifid system: two pyelocaliceal systems join at the Methods: The cases of: Lacramioara, 10 years old- both ureteropelvic junction (bifid pelvis), or 2 ureters join sides duplication of renal pelvis and calyces, Alexandra 7 before draining into the urinary bladder (bifid ureters). years old - duplicity of renal pelvis and calyces on left side, Double ureters: two ureters open separately into the Denis 1 month old and Bianca 1 year old - complete renal pelvis superiorly and drain separately into the unilateral duplicated collecting system. Results: Presenting bladder or genital tract. reasons: recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary Upper and lower pole ureters: upper and lower pole incontinence, bronchopneumonia and sepsis in the neonate. ureters drain a duplex kidney's upper and lower poles, Using the ultrasound investigation, urinary tract respectively. (2) abnormalities are being seen and then confirmed by MRI. Duplicated collecting system is found unilateral, as Therapeutic attitudes differ depending on the severity of the well as bilateral and for most of the times, genitourinary malformation. -

Obstructing Calculus in a Single Limb of A

ical C lin as Shawish and Shawish, J Clin Case Rep 2019, 9:9 f C e o R l e a p n o r r u t s o J Journal of Clinical Case Reports ISSN: 2165-7920 Case Report Open Access Obstructing Calculus in a Single Limb of a Duplicated Ureter: A Recall of the Surgical Anatomy and the Variable Ureter Anomalies Shawish FA1* and Shawish WA2 1Department of Urology, Dr. Suleiman Al-Habib Hospital, Dubai, UAE 2Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Abstract The ureter is a common site of congenital anomalies which may be associated with a considerable morbidity particularly among young patient. The congenital anomalies of the ureter coexist with multitude of other urinary tract anomalies, but it may occur independently. It is more common in females. The complete duplication of the ureter may not produce symptoms which would suggest the presence of malformation. Therefore, such anomaly may not become apparent until later in life. Further, this anomaly might not be recognized prior to the surgery and hence, missing of the stone is highly possible. Herein we present a case of complete ureter duplicate with an obstructive stone located close to VUJ of one limb of the duplicate. A sound knowledge of the surgical anatomy and of the congenital ureter anomalies is essential for correct diagnosis and appropriate management. Keywords: Duplicated ureter; Unenhanced CT KUB; Vesico-ureteric of left VUJ (Figure 1). Subsequent plain CT KUB scan emphasize the junction; Ultrasonography; Ureterosc opy; Calculus presence of the calculus impacted at the same described location. -

Renal Agenesis with Ureterocele, Duplicated Megaureter and Translocation of Seminal Vesicle: a Case Report and Review of the Literature

Submitted: 19 April, 2021 Accepted: 10 June, 2021 Online Published: 06 August, 2021 DOI:10.31083/jomh.2021.088 Case Report Renal agenesis with ureterocele, duplicated megaureter and translocation of seminal vesicle: a case report and review of the literature Jae Joon Park1, Woong Bin Kim2, Kwang Woo Lee2, Jun Mo Kim2, Young Ho Kim2, Ahrim Moon3, Jae Heon Kim1, Si Hyun Kim4, Sang Wook Lee2;* 1Department of Urology, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University Medical College, 04401 Seoul, Republic of Korea 2Department of Urology, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine, 14584 Bucheon, Republic of Korea 3Department of Pathology, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine, 14584 Bucheon, Republic of Korea 4Department of Urology, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine, 31151 Cheonan, Republic of Korea *Correspondence: [email protected] (Sang Wook Lee) Abstract Background: Renal agenesis is a congenital malformation that occurs due to the inhibition of metanephric blastema induction due to a decrease in ureteric bud activity. Although renal agenesis is not very rare, unilateral renal agenesis with ureterocele occurs rarely, and the coexistance of unilateral renal agenesis, ureterocele, and blind ended proximal ureter is very rare. Recently, we experienced a case of left renal agenesis with huge ureterocele, blind ended proximal ureter, and duplicated ureter on Computed tomography (CT) of a 17-year-old man who visited our emergency department with hematuria. Ureterocelectomy and nephrectomy were performed, and a translocation of seminal vesicle was also observed. This case is a very rare case, so we judged that it may be helpful in making treatment decisions in similar cases later. -

Duplicated Collecting System with Ectopic Vaginal Implantation

Behaeghe, M, et al. Duplicated Collecting System with Ectopic Vaginal Implantation. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 2018; 102(1): 62, 1–3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/jbsr.1524 CASE REPORT Duplicated Collecting System with Ectopic Vaginal Implantation Maxim Behaeghe*, Patrick Seynaeve† and Koenraad Verstraete* We present a case of a 54-year-old woman with a left-sided complete duplication of the ureter. The upper moiety drains in the proximal third of the vagina, which results in an ureterocele and urinary incontinence. The ureteral orifice of lower moiety ureter was normal. Duplication of the ureters with distal, infra- sphincteric, vaginal implantation is an uncommon congenital anomaly and a rarely seen entity in adulthood as a cause of urinary incontinence. MR colpocystodefecography showed an ureterocele in between the bladder and the rectum. Computed-tomography showed the duplicated ureters and ectopic ureter with proximal implantation on the renal upper pole and distal implantation on the proximal third of the vagina. Keywords: Ectopic ureter; Ectopic vaginal implantation; Duplicated collecting system; Complete duplication; Ureterocele; Incontinence; Reflux Introduction upper pole of the left kidney (Figure 3). The contralateral The combination of a duplicated collecting system with kidney and ureter were normal. ectopic implantation is a rare congenital anomaly, in con- trast to a duplicated collecting system, which is more com- Discussion mon. The duplicated renal collecting system can be partial Duplication of the ureters is a relatively common or complete, depending on a partial or full-length sepa- congenital anomaly with an incidence of 0.7% in the ration of the ureters. -

Complete Left Ureteric Duplication with Left Ectopic Ureter Presenting As Ureterovaginal Fistula in a Nigerian Girl; a Case Report

Central Journal of Urology and Research Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report *Corresponding author Olushola Jeremiah Ajamu, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Ladoke Akintola University of Complete Left Ureteric Technology Teaching Hospital, Ogbomosho, PMB 4007, Ogbomosho, Oyo State, Nigeria; Tel: 23-480-349-749- 56; Email: Duplication with Left Submitted: 16 April 2018 Accepted: 30 May 2018 Published: 01 June 2018 Ectopic Ureter Presenting as ISSN: 2379-951X Copyright Ureterovaginal Fistula in a © 2018 Ajamu et al. OPEN ACCESS Nigerian Girl; A Case Report Keywords • Duplicated ureters Olushola Jeremiah Ajamu1 and Linus Ikechuckwu Okeke2 • Ectopic 1Department of Urology, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, • Urinary incontinence Nigeria • Re-implantation 2Division of Urology, University College Hospital, Ibadan and University of Ibadan, Nigeria Abstract Ureteric duplication is associated with ectopic ureter and manifests in many ways. It is commonly seen in the female gender. Most Patients with this anomaly present with recurrent urinary tract infections, total urinary incontinence and enuresis while others may remain asymptomatic. We present a 26 year old nulliparous Nigerian lady with complete left duplicated ureters who was initially leaking urine intermittently from a spot on the vestibulum but developed continuous leakage of urine per vagina after a surgical attempt in another hospital. She had exploratory laparotomy at our hospital and re-implantation of the left duplicated ureters in the bladder. A piece of gauze from previous surgery was found to have eroded into the proximal third of the rectum. This was removed and rectal repair done. Duplicated ureters should be suspected in female patients presenting with urinary incontinence and their care should be left to experienced urologists to prevent complications. -

Unilateral Incomplete Duplicated Ureter – a Clinical and Embryological Insight

Available online at www.ijmrhs.com International Journal of Medical Research & ISSN No: 2319-5886 Health Sciences, 2016, 5, 8:68-70 Unilateral incomplete duplicated ureter – A clinical and embryological insight Parveen Ojha and Seema Prakash Department of Anatomy, R. N. T. Medical College, Udaipur Corresponding Email: [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Unilateral incomplete duplication of ureter of right kidney was observed during routine dissection of an adult male cadaver at R.N.T. Medical College, Udaipur. Two ureters of right kidney joined just before entrance into urinary bladder and opened in urinary bladder by a single ureteric orifice. Duplication is one of the commonest anomaly of genitourinary system and may be accompanied by other congenital anomaly or it may be a cause of urinary tract infections, calculi or it may get injured during pelvic surgeries. In this case study we have discussed embryological development and clinical implications of such type of anomaly. Key words: Duplication, ureter, bifid _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Ureter is a muscular tube of 25-30cm length, continuous superiorly with funnel shaped structure called renal pelvis and inferiorly it opens into the lateral angle of the base of the urinary bladder. Ureters develop from ureteric bud which penetrates the metanephric tissue [1]. Duplication of ureter results from early splitting of ureteric bud [2].One such case of duplication was observed by us during routine dissection of an adult male cadaver. Duplication of ureter may remain asymptomatic or it may cause repeated urinary tract infections or calculi. It may get injured during pelvic surgeries. Case study - (Fig-1) During routine dissection of abdomen of an adult male cadaver two uerters were noticed emerging from the right kidney.