The Launch of the Indian Premier League

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Ugust Ed Itio N

AUGUST EDITION AUGUST A message from class eleven-: After returning from the summer vacation, there has been a lot of enthusiasm among the class elevens as well as in the other classes too. The soccer season, the most exhilarating sports season of the year has also arrived. Not being able to reach the semi-finals of the Jackie Tournament was disappointing for us, but we must under- stand that one must learn from one’s mistakes and move on. After the Board results, we heaved sighs of relief and geared our- selves for an exciting new term. There are a lot of new faces in class and it is fun making new friends. Interacting with new people helps us to learn a lot more whether it is about a new country or the interests, hobbies and general views of another individual. Everyone is very excited about the upcoming House plays even though our first terminal examinations are round the corner. We have started pre- paring for them and hope to score good marks. All the best for the upcoming events and the rest of the year. EXCELSIOR! BY- Parangat Sharma (XI-S) EXCELSIOR A Mathematical Challenge But you will have to rise again and once had make your dreams come true. To do so much more for my mom Try, try and try Every step you take will light your and dad The more I try way To give them more joy and a little The more I cry. It doesn’ t matter if one step gives less pain It’s like Chemistry and Physics you only a single ray A little more sunshine and a little As difficult as learning them For things will get better and less rain. -

History of Men Test Cricket: an Overview Received: 14-11-2020

International Journal of Physiology, Nutrition and Physical Education 2021; 6(1): 174-178 ISSN: 2456-0057 IJPNPE 2021; 6(1): 174-178 © 2021 IJPNPE History of men test cricket: An overview www.journalofsports.com Received: 14-11-2020 Accepted: 28-12-2020 Sachin Prakash and Dr. Sandeep Bhalla Sachin Prakash Ph.D., Research Scholar, Abstract Department of Physical The concept of Test cricket came from First-Class matches, which were played in the 18th century. In the Education, Indira Gandhi TMS 19th century, it was James Lillywhite, who led England to tour Australia for a two-match series. The first University, Ziro, Arunachal official Test was played from March 15 in 1877. The first-ever Test was played with four balls per over. Pradesh, India While it was a timeless match, it got over within four days. The first notable change in the format came in 1889 when the over was increased to a five-ball, followed by the regular six-ball over in 1900. While Dr. Sandeep Bhalla the first 100 Tests were played as timeless matches, it was since 1950 when four-day and five-day Tests Director - Sports & Physical were introduced. The Test Rankings was introduced in 2003, while 2019 saw the introduction of the Education Department, Indira World Test Championship. Traditionally, Test cricket has been played using the red ball, as it is easier to Gandhi TMS University, Ziro, spot during the day. The most revolutionary change in Test cricket has been the introduction of Day- Arunachal Pradesh, India Night Tests. Since 2015, a total of 11 such Tests have been played, which three more scheduled. -

Measuring Customer Discrimination: Evidence from the Professional Cricket League in India

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11319 Measuring Customer Discrimination: Evidence from the Professional Cricket League in India Pramod Kumar Sur Masaru Sasaki FEBRUARY 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11319 Measuring Customer Discrimination: Evidence from the Professional Cricket League in India Pramod Kumar Sur GSE, Osaka University Masaru Sasaki GSE, Osaka University and IZA FEBRUARY 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11319 FEBRUARY 2018 ABSTRACT Measuring Customer Discrimination: Evidence from the Professional Cricket League in India Research in the field of customer discrimination has received relatively little attention even if the theory of discrimination suggests that customer discrimination may exist in the long run whereas employer and employee discrimination may not. -

Will T20 Clean Sweep Other Formats of Cricket in Future?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Subhani, Muhammad Imtiaz and Hasan, Syed Akif and Osman, Ms. Amber Iqra University Research Center 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/45144/ MPRA Paper No. 45144, posted 16 Mar 2013 09:41 UTC Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Muhammad Imtiaz Subhani Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Amber Osman Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Syed Akif Hasan Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 1513); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Bilal Hussain Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Abstract Enthralling experience of the newest format of cricket coupled with the possibility of making it to the prestigious Olympic spectacle, T20 cricket will be the most important cricket format in times to come. The findings of this paper confirmed that comparatively test cricket is boring to tag along as it is spread over five days and one-days could be followed but on weekends, however, T20 cricket matches, which are normally played after working hours and school time in floodlights is more attractive for a larger audience. -

IPL 2014 Schedule

Page: 1/6 IPL 2014 Schedule Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders 1st IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 16, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Delhi Daredevils vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 2nd IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 17, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Kings XI Punjab 3rd IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals 4th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Mumbai Indians 5th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Kolkata Knight Riders vs Delhi Daredevils 6th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Kings XI Punjab 7th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 20, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Daredevils 8th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 21, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Kings XI Punjab vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 9th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 22, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Chennai Super Kings 10th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 23, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight Riders Page: 2/6 11th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 24, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Daredevils 12th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 25, 2014 -

Cobbling Together the Dream Indian Eleven

COBBLING TOGETHER THE DREAM INDIAN ELEVEN Whenever the five selectors, often dubbed as the five wise men with the onerous responsibility of cobbling together the best players comprising India’s test cricket team, sit together to pick the team they feel the heat of the country’s collective gaze resting on them. Choosing India’s cricket team is one of the most difficult tasks as the final squad is subjected to intense scrutiny by anybody and everybody. Generally the point veers round to questions such as why batsman A was not picked or bowler B was dropped from the team. That also makes it a very pleasurable hobby for followers of the game who have their own views as to who should make the final 15 or 16 when the team is preparing to leave our shores on an away visit or gearing up to face an opposition on a tour of our country. Arm chair critics apart, sports writers find it an enjoyable professional duty when they sit down to select their own team as newspapers speculate on the composition of the squad pointing out why somebody should be in the team at the expense of another. The reports generally appear on the sports pages on the morning of the team selection. This has been a hobby with this writer for over four decades now and once the team is announced, you are either vindicated or amused. And when the player, who was not in your frame goes on to play a stellar role for the country, you inwardly congratulate the selectors for their foresight and knowledge. -

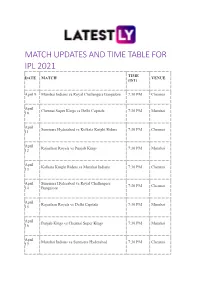

Match Updates and Time Table for Ipl 2021 Time Date Match Venue (Ist)

MATCH UPDATES AND TIME TABLE FOR IPL 2021 TIME DATE MATCH VENUE (IST) April 9 Mumbai Indians vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 7:30 PM Chennai April Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Mumbai 10 April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Chennai 11 April Rajasthan Royals vs Punjab Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 12 April Kolkata Knight Riders vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 13 April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Royal Challengers 7:30 PM Chennai 14 Bangalore April Rajasthan Royals vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Mumbai 15 April Punjab Kings vs Chennai Super Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 16 April Mumbai Indians vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 7:30 PM Chennai 17 April Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight 3:30 PM Chennai 18 Riders April Delhi Capitals vs Punjab Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 18 April Chennai Super Kings vs Rajasthan Royals 7:30 PM Mumbai 19 April Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 20 April Punjab Kings vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 3:30 PM Chennai 21 April Kolkata Knight Riders vs Chennai Super Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 21 April Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Rajasthan Royals 7:30 PM Mumbai 22 April Punjab Kings vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 23 April Rajasthan Royals vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Mumbai 24 April Chennai Super Kings vs Royal Challengers 3:30 PM Mumbai 25 Bangalore April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Chennai 25 April Punjab Kings vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Ahmedabad 26 April Delhi Capitals vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 7:30 PM Ahmedabad 27 April Chennai Super Kings vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 7:30 -

The Natwest Series 2001

The NatWest Series 2001 CONTENTS Saturday23June 2 Match review – Australia v England 6 Regulations, umpires & 2002 fixtures 3&4 Final preview – Australia v Pakistan 7 2000 NatWest Series results & One day Final act of a 5 2001 fixtures, results & averages records thrilling series AUSTRALIA and Pakistan are both in superb form as they prepare to bring the curtain down on an eventful tournament having both won their last group games. Pakistan claimed the honours in the dress rehearsal for the final with a memo- rable victory over the world champions in a dramatic day/night encounter at Trent Bridge on Tuesday. The game lived up to its billing right from the onset as Saeed Anwar and Saleem Elahi tore into the Australia attack. Elahi was in particularly impressive form, blast- ing 79 from 91 balls as Pakistan plundered 290 from their 50 overs. But, never wanting to be outdone, the Australians responded in fine style with Adam Gilchrist attacking the Pakistan bowling with equal relish. The wicketkeep- er sensationally raced to his 20th one-day international half-century in just 29 balls on his way to a quick-fire 70. Once Saqlain Mushtaq had ended his 44-ball knock however, skipper Waqar Younis stepped up to take the game by the scruff of the neck. The pace star is bowling as well as he has done in years as his side come to the end of their tour of England and his figures of six for 59 fully deserved the man of the match award and to take his side to victory. -

Sports Terminologies & List of Sports Trophies/Cups

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co Sports Terminologies Sports Terminology Service, Deuce, Smash, Drop, Let, Game, Love, Double Badminton Fault. Baseball Pitcher, Strike, Diamond, Bunting, Home Run, Put Out. Alley-oop, Dunk, Box-Out, Carry the Ball, Cherry Picking, Basketball Lay-up, Fast Break, Traveling Jigger, Break, Scratch, Cannons, Pot, Cue, In Baulk, Pot Billiards Scratch, In Off. Boxing Jab, Hook, Punch, Knock-out, Upper cut, Kidney Punch. Revoke, Ruff, Dummy, Little Slam, Grand Slam, Trump, Bridge Diamonds, Tricks. Chess Gambit, Checkmate, Stalemate, Check. LBW, Maiden over, Rubber, Stumped, Ashes, Hat-trick, Leg Bye, follow on, Googly, Gulley, Silly Point, Duck, Run, Cricket Drive, no ball, Cover point, Leg Spinner, Wicket Keeper, Pitch, Crease, Bowling, Leg-Break, Hit – Wicket, Bouncer, Stone-Walling. Dribble, Off-Side, Penalty, Throw-in, Hat-Trick, Foul, Football Touch, Down, Drop Kick, Stopper Hole, Bogey, Put, Stymie, Caddie, Tee, Links, Putting the Golf green. Bully, Hat-Trick, Short corner, Stroke, Striking Circle, Hockey Penalty corner, Under cutting, Scoop, Centre forward, Carry, Dribble, Goal, Carried. Horse Racing Punter, Jockey, Place, Win, Protest. Volley, Smash, Service, Back-hand-drive,Let, Advantage, Lawn Tennis Deuce Shooting Bag, Plug, Skeet, Bull's eye Swimming Stroke. Table Tennis Smash, Drop, Deuce, Spin, Let, Service Volley Ball Blocking, Doubling, Smash, Point, Serve, Volley Wrestling Freestyle, Illegal Hold, Nearfall, Clamping 2 www.gradeup.co List of Sports Trophies/ Cups Sports Trophies/ Cups Ashes Cup, Asia Cup, C.K. Naidu Trophy, Deodhar Trophy, Duleep Trophy, Gavaskar Border Trophy, G.D. Birla Trophy, Gillette Cup, ICC World Cup, Irani Trophy, Jawaharlal Nehru Cup, Cricket Rani Jhansi Trophy, Ranji Trophy, Rohinton Barcia Trophy, Rothmans Cup, Sahara Cup, Sharjah Cup, Singer Cup, Titan Cup, Vijay Hazare Trophy, Vijay Merchant Trophy, Wisden Trophy, Wills Trophy. -

Balance Sheet Merge Satistics & Color Bitmap.Cdr

MADHYA PRADESH CRICKET ASSOCIATION Holkar Stadium, Khel Prashal, Race Course Road, INDORE-452 003 (M.P.) Phone : (0731) 2543602, 2431010, Fax : (0731) 2534653 e-mail : [email protected] Date : 17th Aug. 2011 MEETING NOTICE To, All Members, Madhya Pradesh Cricket Association. The Annual General Body Meeting of Madhya Pradesh Cricket Association will be held at Holkar Stadium, Khel Prashal, Race Course Road, Indore on 3rd September 2011 at 12 Noon to transact the following business. A G E N D A 1. Confirmation of the minutes of the previous Annual General Body Meeting held on 22.08.2010. 2. Adoption of Annual Report for 2010-2011. 3. Consideration and approval of Audited Statement of accounts and audit report for the year 2010-2011. 4. To consider and approve the Proposed Budget for the year 2011-2012. 5. Appointment of the Auditors for 2011-2012. 6. Any other matter with the permission of the Chair. (NARENDRA MENON) Hon. Secretary Note : 1. If you desire to seek any information, you are requested to write to Hon. Secretary latest by 28th Aug. 2011. 2. The Quorum for meeting is One Third of the total membership. If no quorum is formed, the Meeting will be adjourned for 15 minutes. No quorum will be necessary for adjourned meeting. The adjourned meeting will be held at the same place. THE MEETING WILL BE FOLLOWED BY LUNCH. 1 MADHYA PRADESH CRICKET ASSOCIATION, INDORE UNCONFIRMED MINUTES OF ANNUAL GENERAL BODY MEETING HELD ON 22nd AUGUST 2010 A meeting of the General Body of MPCA was held on Sunday 22nd Aug’ 2010 at Usha Raje Cricket Centre at 12.00 noon. -

Presented Here Are the ACS's Answers to a Number of General

Presented here are the ACS’s answers to a number of general questions about the statistics and history of cricket that arise from time to time. It is hoped that they will be of interest both to relative newcomers to these aspects of the game, and to a more general readership. Any comments, or suggestions for further questions to be answered in this section, should be sent to [email protected] Please note that this section is for general questions only, and not for dealing with specific queries about cricket records, or about individual cricketers or their performances. 1 THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF CRICKET What are the three formats in which top-level cricket is played? At the top level of the game – at international level, and at the level of counties in England and their equivalent in other leading countries – cricket is played in three different ‘formats’. The longest-established is ‘first-class cricket’, which includes Test matches as well as matches in England’s County Championship, the Sheffield Shield in Australia, the Ranji Trophy in India, and equivalent competitions in other countries. First-class matches are scheduled to be played over at least 3 days, and each team is normally entitled to have two innings in this period. Next is ‘List A’ cricket – matches played on a single day and in which each team is limited in the number of overs that it can bat or bowl. Nowadays, List A matches are generally arranged to be played with a limit of 50 overs per side. International matches of this type are referred to as ‘One-Day Internationals’, or ODIs. -

Name – Nitin Kumar Class – 12Th 'B' Roll No. – 9752*** Teacher

ON Name – Nitin Kumar Class – 12th ‘B’ Roll No. – 9752*** Teacher – Rajender Sir http://www.facebook.com/nitinkumarnik Govt. Boys Sr. Sec. School No. 3 INTRODUCTION Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of 11 players on a field, at the centre of which is a rectangular 22-yard long pitch. One team bats, trying to score as many runs as possible while the other team bowls and fields, trying to dismiss the batsmen and thus limit the runs scored by the batting team. A run is scored by the striking batsman hitting the ball with his bat, running to the opposite end of the pitch and touching the crease there without being dismissed. The teams switch between batting and fielding at the end of an innings. In professional cricket the length of a game ranges from 20 overs of six bowling deliveries per side to Test cricket played over five days. The Laws of Cricket are maintained by the International Cricket Council (ICC) and the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) with additional Standard Playing Conditions for Test matches and One Day Internationals. Cricket was first played in southern England in the 16th century. By the end of the 18th century, it had developed into the national sport of England. The expansion of the British Empire led to cricket being played overseas and by the mid-19th century the first international matches were being held. The ICC, the game's governing body, has 10 full members. The game is most popular in Australasia, England, the Indian subcontinent, the West Indies and Southern Africa.