Francis Gbadago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana: State Treatment of LGBTQI+ Persons

Ghana: State treatment of LGBTQI+ persons March 2021 © Asylos and ARC Foundation, 2021 This publication is covered by the Creative Commons License BY-NC 4.0 allowing for limited use provided the work is properly credited to Asylos and ARC Foundation and that it is for non-commercial use. Asylos and ARC Foundation do not hold the copyright to the content of third-party material included in this report. Reproduction or any use of the images/maps/infographics included in this report is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder(s). This report was produced with the kind support of the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Feedback and comments Please help us to improve and to measure the impact of our publications. We would be extremely grateful for any comments and feedback as to how the reports have been used in refugee status determination processes, or beyond, by filling out our feedback form: https://asylumresearchcentre.org/feedback/. Thank you. Please direct any comments or questions to [email protected] and [email protected] Cover photo: © M Four Studio/shutterstock.com 2 Contents 2 CONTENTS 3 EXPLANATORY NOTE 5 BACKGROUND ON THE RESEARCH PROJECT 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 FEEDBACK AND COMMENTS 7 WHO WE ARE 7 LIST OF ACRONYMS 8 RESEARCH TIMEFRAME 9 SOURCES CONSULTED 9 1. LEGAL CONTEXT 13 1.1 CONSTITUTION 13 1.2 CRIMINAL CODE 16 1.3 OTHER RELEVANT LEGISLATION AFFECTING LGBTQI+ PERSONS 20 2. LAW IN PRACTICE 24 2.1 ARRESTS OF LGBTQI+ PERSONS 26 2.1.1 Arrests of gay men 29 2.1.2 Arrests of lesbian women 31 2.1.3 Arrests of cross-dressers 32 2.2 PROSECUTIONS UNDER LAWS THAT ARE DEPLOYED AGAINST LGBTQI+ COMMUNITY BECAUSE OF THEIR PERCEIVED DIFFERENCE 33 2.3 CONVICTIONS UNDER LAWS THAT ARE DEPLOYED AGAINST LGBTQI+ COMMUNITY BECAUSE OF THEIR PERCEIVED DIFFERENCE 36 3. -

Ghana Risk Review: June 2020

1 June 20 Ghana Risk Review: June 2020 Prepared for Omega Risk Solutions by Keith Campbell Consulting Ltd www.kccltd.co.uk Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................ 3 COUNTRY PROFILE ................................................................................. 1_Toc44285126 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 5 POLITICAL ............................................................................................................................... 19 MAY - JUNE 2020 HEADLINES ................................................................................................... 19 POLITICAL STABILITY ................................................................................................................. 20 GOVERNMENT EFFECTIVENESS ................................................................................................... 21 INSTITUTIONAL BALANCE/FUNCTIONING ..................................................................................... 23 CONTRACT FRUSTRATION .......................................................................................................... 24 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ....................................................................................................... 25 OPERATIONAL ................................................................................................................ 27 MAY - JUNE -

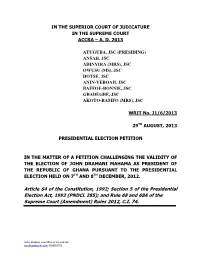

Section 5 of the Presidential Election Act, 1992 (PNDCL 285); and Rule 68 and 68A of the Supreme Court (Amendment) Rules 2012, C.I

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF JUDICATURE IN THE SUPREME COURT ACCRA – A. D. 2013 ATUGUBA, JSC (PRESIDING) ANSAH, JSC ADINYIRA (MRS), JSC OWUSU (MS), JSC DOTSE, JSC ANIN-YEBOAH, JSC BAFFOE-BONNIE, JSC GBADEGBE, JSC AKOTO-BAMFO (MRS), JSC WRIT No. J1/6/2013 29TH AUGUST, 2013 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION PETITION IN THE MATTER OF A PETITION CHALLENGING THE VALIDITY OF THE ELECTION OF JOHN DRAMANI MAHAMA AS PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA PURSUANT TO THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION HELD ON 7TH AND 8TH DECEMBER, 2012. Article 64 of the Constitution, 1992; Section 5 of the Presidential Election Act, 1992 (PNDCL 285); and Rule 68 and 68A of the Supreme Court (Amendment) Rules 2012, C.I. 74. Victor Brobbey, Law Office of Ayine & Felli [email protected], 0266861752 BETWEEN: 1. NANA ADDO DANKWA AKUFO-ADDO ] 1ST PETITIONER H/No. 2, Onyaa Crescent, Nima, Accra. ] 2. DR. MAHAMUDU BAWUMIA ] 2ND PETITIONER H/No. 10, 6th Estate Road, Kanda Estates, Accra. ] 3. JAKE OTANKA OBETSEBI-LAMPTEY ] 3RD PETITIONER 24, 4th, Circular Road, Cantonment, Accra. ] AND 1. JOHN DRAMANI MAHAMA ] 1ST RESPONDENT Castle, Castle Road, Osu, Accra. ] 2. THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION ] 2ND RESPONDENT National Headquarters of the Electoral ] Commission, 6th Avenue, Ridge, Accra. 3. NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CONGRESS (NDC)] 3RD RESPONDENT National Headquarters, Accra. ] JUDGMENT ATUGUBA, JSC By their second amended petition dated the 8th day of February 2013 the petitioners claimed, as stated at p.9 of the Written Address of their counsel; ―(1) that John Dramani Mahama, the 1st respondent herein, was not validly elected President of the Republic of Ghana; (2) that Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, the 1st petitioner herein, rather was validly elected President of the Republic of Ghana; (3) consequential orders as to this Court may seem meet.‖ Although the petitioners complained about the transparency of the voters‘ register and its non or belated availability before the elections, this line of their case does not seem to have been strongly pressed. -

Ghana Social Science Journal, Volume 8, Numbers 1&2, 2011

GHANA SOCIAL SCIENCE JOURNAL Volume 8, Numbers 1&2, 2011 Faculty of Social Science University of Ghana, Legon, Accra INTE S GRI PROCEDAMU Ghana Social Science Journal, Volume 8, Numbers 1 & 2, 2011 Editors Dzodzi Tsikata Clara Fayorsey Editorial Committee Samuel Agyei-Mensah - Chairman Abena D. Oduro - Member Samuel Nii Ardey Codjoe - Member Dzodzi Tsikata - Member Clara Fayorsey - Member International Advisory Board Joseph Ayee, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa Emmanuel Akyeampong, Harvard University, USA Jean Allman, Washington University in St. Louis, USA. Timothy Insoll, University of Manchester, UK Michael Lofchie, University of California, Los Angeles, USA Maureen Mackintosh, The Open University, UK Amina Mama, University of California, Davis, USA Adebayo Olukoshi, UN African Institute for Economic Development and Planning (IDEP), Senegal. Barry Riddell, Queens University, Canada. Mohammed Salih, Erasmus University of Rotterdam, Netherlands. Rotimi Suberu, Bennington College, USA © Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, 2011 ISSN: 0855-4730 All rights reserved; no part of this journal may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission o f the publishers. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this journal will be liable to criminal prosecution and claims for damages. Published by the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ghana P.O. Box 72, Legon, Ghana Tel. No. (233-21) 500179 E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Yamens Press Limited P.O. Box AN 6045 Tel No. (233-302) 223222/235036 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Volume 8 Numbers 1 & 2 2011 Tariff Reforms, Food Prices, and Consumer Welfare in Ghana during the 1990s Charles Ackah 1-21 An Assessment of Feedback Effects in the Inflation-Economic Growth Nexus: Evidence from Nigeria S.I. -

CCG Observation Report1

Christian Council Of Ghana ObElsecetiornv Evaenttso annd Report 7th December, 2012 WE SOW WE SOW Christian Council Of Ghana 2012 PRESIDENTIAL & PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 7th December, 2012 Compiled By: GEORGE SAGOE-ADDY CToabnlete ofnt OVERVIEW AND PREPARATION FOR ELECTION 2012................................................5 Context........................................................................................................5 Training of Election Observers......................................................................6 Advocacy Events..........................................................................................8 Sensitisation workshops..........................................................................8 Production and Airing of Peace Messages ...............................................9 Church Participation for Peaceful Election 2012.......................................9 EMINENT PERSONS GROUP........................................................................................9 CCG ELECTION OBSERVATION 2012........................................................................11 Pre- Election reports.....................................................................................11 Election Day................................................................................................12 Before Voting.........................................................................................12 Voting Period.........................................................................................13