West Nile Virus Surveillance in Washington State, 2002 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty Years of Surveillance for Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus In

Oliver et al. Parasites & Vectors (2018) 11:362 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2950-1 RESEARCH Open Access Twenty years of surveillance for Eastern equine encephalitis virus in mosquitoes in New York State from 1993 to 2012 JoAnne Oliver1,2*, Gary Lukacik3, John Kokas4, Scott R. Campbell5, Laura D. Kramer6,7, James A. Sherwood1 and John J. Howard1 Abstract Background: The year 1971 was the first time in New York State (NYS) that Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) was identified in mosquitoes, in Culiseta melanura and Culiseta morsitans. At that time, state and county health departments began surveillance for EEEV in mosquitoes. Methods: From 1993 to 2012, county health departments continued voluntary participation with the state health department in mosquito and arbovirus surveillance. Adult female mosquitoes were trapped, identified, and pooled. Mosquito pools were tested for EEEV by Vero cell culture each of the twenty years. Beginning in 2000, mosquito extracts and cell culture supernatant were tested by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Results: During the years 1993 to 2012, EEEV was identified in: Culiseta melanura, Culiseta morsitans, Coquillettidia perturbans, Aedes canadensis (Ochlerotatus canadensis), Aedes vexans, Anopheles punctipennis, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, Psorophora ferox, Culex salinarius, and Culex pipiens-restuans group. EEEV was detected in 427 adult mosquito pools of 107,156 pools tested totaling 3.96 million mosquitoes. Detections of EEEV occurred in three geographical regions of NYS: Sullivan County, Suffolk County, and the contiguous counties of Madison, Oneida, Onondaga and Oswego. Detections of EEEV in mosquitoes occurred every year from 2003 to 2012, inclusive. EEEV was not detected in 1995, and 1998 to 2002, inclusive. -

HEALTHINFO H E a Lt H Y E Nvironment T E a M Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE)

H aldimand-norfolk HE a LT H U N I T HEALTHINFO H e a lt H y e nvironment T E a m eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) What is eastern equine encephalitis? Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), some- times called sleeping sickness or Triple E, is a rare but serious viral disease spread by infected mosquitoes. How is eastern equine encephalitis transmitted? The Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEv) can infect a wide range of hosts including mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. Infection occurs through the bite of an infected mosquito. The virus itself is maintained in nature through a cycle between Culiseta melan- ura mosquitoes and birds. Culiseta mel- anura mosquitoes feed almost exclusively on birds, so they are not considered an important vector of EEEv to humans or other mammals. Transmission of EEEv to humans requires mosquito species capable of creating a “bridge” between infected birds and uninfected mammals. Other species of mosquitoes (including Coquiletidia per- Coast states. In Ontario, EEEv has been ticipate in outdoor recreational activities turbans, Aedes vexans, Ochlerotatus found in horses that reside in the prov- have the highest risk of developing EEE sollicitans and Oc. Canadensis) become ince or that have become infected while because of greater exposure to potentially infected when they feed on infected travelling. infected mosquitoes. birds. These infected mosquitoes will then occasionally feed on horses, humans Similar to West Nile virus (WNv), the People of all ages are at risk for infection and other mammals, transmitting the amount of virus found in nature increases with the EEE virus but individuals over age virus. -

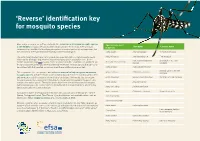

Identification Key for Mosquito Species

‘Reverse’ identification key for mosquito species More and more people are getting involved in the surveillance of invasive mosquito species Species name used Synonyms Common name in the EU/EEA, not just professionals with formal training in entomology. There are many in the key taxonomic keys available for identifying mosquitoes of medical and veterinary importance, but they are almost all designed for professionally trained entomologists. Aedes aegypti Stegomyia aegypti Yellow fever mosquito The current identification key aims to provide non-specialists with a simple mosquito recog- Aedes albopictus Stegomyia albopicta Tiger mosquito nition tool for distinguishing between invasive mosquito species and native ones. On the Hulecoeteomyia japonica Asian bush or rock pool Aedes japonicus japonicus ‘female’ illustration page (p. 4) you can select the species that best resembles the specimen. On japonica mosquito the species-specific pages you will find additional information on those species that can easily be confused with that selected, so you can check these additional pages as well. Aedes koreicus Hulecoeteomyia koreica American Eastern tree hole Aedes triseriatus Ochlerotatus triseriatus This key provides the non-specialist with reference material to help recognise an invasive mosquito mosquito species and gives details on the morphology (in the species-specific pages) to help with verification and the compiling of a final list of candidates. The key displays six invasive Aedes atropalpus Georgecraigius atropalpus American rock pool mosquito mosquito species that are present in the EU/EEA or have been intercepted in the past. It also contains nine native species. The native species have been selected based on their morpho- Aedes cretinus Stegomyia cretina logical similarity with the invasive species, the likelihood of encountering them, whether they Aedes geniculatus Dahliana geniculata bite humans and how common they are. -

A Synopsis of the Mosquitoes of Missouri and Their Importance from a Health Perspective Compiled from Literature on the Subject

A Synopsis of The Mosquitoes of Missouri and Their Importance From a Health Perspective Compiled from Literature on the Subject by Dr. Barry McCauley St. Charles County Department of Community Health and the Environment St. Charles, Missouri Mark F. Ritter City of St. Louis Health Department St. Louis, Missouri Larry Schaughnessy City of St. Peters Health Department St. Peters, Missouri December 2000 at St. Charles, Missouri This handbook has been prepared for the use of health departments and mosquito control pro- fessionals in the mid-Mississippi region. It has been drafted to fill a perceived need for a single source of information regarding mosquito population types within the state of Missouri and their geographic distribution. Previously, the habitats, behaviors and known distribution ranges of mosquitoes within the state could only be referenced through consultation of several sources - some of them long out of print and difficult to find. It is hoped that this publication may be able to fill a void within the literature and serve as a point of reference for furthering vector control activities within the state. Mosquitoes have long been known as carriers of diseases, such as malaria, yellow fever, den- gue, encephalitis, and heartworm in dogs. Most of these diseases, with the exception of encephalitis and heartworm, have been fairly well eliminated from the entire United States. However, outbreaks of mosquito borne encephalitis have been known to occur in Missouri, and heartworm is an endemic problem, the costs of which are escalating each year, and at the current moment, dengue seems to be making a reappearance in the hotter climates such as Texas. -

Aedes (Ochlerotatus) Vexans (Meigen, 1830)

Aedes (Ochlerotatus) vexans (Meigen, 1830) Floodwater mosquito NZ Status: Not present – Unwanted Organism Photo: 2015 NZB, M. Chaplin, Interception 22.2.15 Auckland Vector and Pest Status Aedes vexans is one of the most important pest species in floodwater areas in the northwest America and Germany in the Rhine Valley and are associated with Ae. sticticus (Meigen) (Gjullin and Eddy, 1972: Becker and Ludwig, 1983). Ae. vexans are capable of transmitting Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEE), Western equine encephalitis virus (WEE), SLE, West Nile Virus (WNV) (Turell et al. 2005; Balenghien et al. 2006). It is also a vector of dog heartworm (Reinert 1973). In studies by Otake et al., 2002, it could be shown, that Ae. vexans can transmit porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in pigs. Version 3: Mar 2015 Geographic Distribution Originally from Canada, where it is one of the most widely distributed species, it spread to USA and UK in the 1920’s, to Thailand in the 1970’s and from there to Germany in the 1980’s, to Norway (2000), and to Japan and China in 2010. In Australia Ae. vexans was firstly recorded 1996 (Johansen et al 2005). Now Ae. vexans is a cosmopolite and is distributed in the Holarctic, Orientalis, Mexico, Central America, Transvaal-region and the Pacific Islands. More records of this species are from: Canada, USA, Mexico, Guatemala, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden Finland, Norway, Spain, Greece, Italy, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), Turkey, Russia, Algeria, Libya, South Africa, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Yemen, Cambodia, China, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia (Lien et al, 1975; Lee et al 1984), Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Palau, Philippines, Micronesia, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, New Zealand (Tokelau), Australia. -

Diptera: Culicidae) in the Laboratory Sara Marie Erickson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2005 Infection and transmission of West Nile virus by Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory Sara Marie Erickson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Erickson, Sara Marie, "Infection and transmission of West Nile virus by Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory" (2005). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18773. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18773 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Infection and transmission of West Nile virus by Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory by Sara Marie Erickson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Entomology Program of Study Committee: Wayne A. Rowley, Major Professor Russell A. Jurenka Kenneth B. Platt Marlin E. Rice Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2005 Copyright © Sara Marie Erickson, 2005. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Sara Marie Erickson has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy lll TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES lV ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION Thesis organization 1 Literature review 1 References 18 CHAPTER 2. -

Linking Bird and Mosquito Data to Assess Spatiotemporal West Nile Virus Risk in Humans

EcoHealth https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-019-01393-8 Ó 2019 EcoHealth Alliance Original Contribution Linking Bird and Mosquito Data to Assess Spatiotemporal West Nile Virus Risk in Humans Benoit Talbot ,1 Merlin Caron-Le´vesque,1 Mark Ardis,2 Roman Kryuchkov,1 and Manisha A. Kulkarni1 1School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Room 217A, 600 Peter Morand Crescent, Ottawa, ON K1G 5Z3, Canada 2GDG Environnement, Trois-Rivie`res, QC, Canada Abstract: West Nile virus (WNV; family Flaviviridae) causes a disease in humans that may develop into a deadly neuroinvasive disease. In North America, several peridomestic bird species can develop sufficient viremia to infect blood-feeding mosquito vectors without succumbing to the virus. Mosquito species from the genus Culex, Aedes and Ochlerotatus display variable host preferences, ranging between birds and mammals, including humans, and may bridge transmission among avian hosts and contribute to spill-over transmission to humans. In this study, we aimed to test the effect of density of three mosquito species and two avian species on WNV mosquito infection rates and investigated the link between spatiotemporal clusters of high mosquito infection rates and clusters of human WNV cases. We based our study around the city of Ottawa, Canada, between the year 2007 and 2014. We found a large effect size of density of two mosquito species on mosquito infection rates. We also found spatiotemporal overlap between a cluster of high mosquito infection rates and a cluster of human WNV cases. Our study is innovative because it suggests a role of avian and mosquito densities on mosquito infection rates and, in turn, on hotspots of human WNV cases. -

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infection in Cats

Current Feline Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Cats Thank You to Our Generous Sponsors: Printed with an Education Grant from IDEXX Laboratories. Photomicrographs courtesy of Bayer HealthCare. © 2014 American Heartworm Society | PO Box 8266 | Wilmington, DE 19803-8266 | E-mail: [email protected] Current Feline Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Cats (revised October 2014) CONTENTS Click on the links below to navigate to each section. Preamble .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 EPIDEMIOLOGY ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Figure 1. Urban heat island profile. BIOLOGY OF FELINE HEARTWORM INFECTION .................................................................................................. 3 Figure 2. The heartworm life cycle. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF FELINE HEARTWORM DISEASE ................................................................................... 5 Figure 3. Microscopic lesions of HARD in the small pulmonary arterioles. Figure 4. Microscopic lesions of HARD in the alveoli. PHYSICAL DIAGNOSIS ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Clinical -

Eastern Equine Encephalitis Center for Food Security and Public Health

Eastern Equine Encephalitis S l i d Eastern Equine e Encephalitis Sleeping Sickness 1 Eastern Encephalitis S In today’s presentation we will cover information regarding the agent l Overview that causes eastern equine encephalomyelitis and its epidemiology. i • Organism We will also talk about the history of this diseases, how it is d • History transmitted, species that it affects, and clinical signs seen in humans e • Epidemiology and animals. Finally, we will address prevention and control • Transmission measures, as well as actions to take if eastern equine • Disease in Humans encephalomyelitis is suspected. [Photo: Horses in a field. Source: 2 • Disease in Animals • Prevention and Control U.S. Department of Agriculture] • Actions to Take Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011 S l i d e THE ORGANISM 3 S Eastern equine encephalomyelitis (EEE) results from infection by the l The Virus respectively named virus in the genus Alphavirus (family i • Family Togaviridae Togaviridae). The numerous isolates of the Eastern equine d • Genus Alphavirus encephalomyelitis virus (EEEV) can be grouped into two variants. e • Two variants The variant found in North America is more pathogenic than the • Mosquito-borne variant that occurs in South and Central America. EEE is a mosquito- • Disease borne, viral infection that can cause severe encephalitis in horses and 4 – Encephalitis in humans and horses humans. [Photo: Electron micrograph of the Eastern equine encephalitis virus. Source: Dr. Fred Murphy and Sylvia Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011 Whitfield/CDC Public Health Image Library] S l i d e HISTORY 5 Center for Food Security and Public Health 2011 1 Eastern Equine Encephalitis S EEE was first isolated from a horse with encephalomyelitis in 1933, l EEE History but it is thought that the disease dates back to 1831 to horses in i • 1831: Massachusetts. -

Aedes & Ochlerotatus Ae Aegypti Ae Albopictus Ae Vexans Oc

Aedes & Ae aegypti Ae Ae vexans Oc Oc fulvus Oc Oc Oc taenio- Oc tormentor Ochlerotatus albopictus bahamensis pallens infirmatus sollicitans rhynchus dark with dark with dark with a dark with yellow with dark with dark with palps white tip; white tip; few white dark dark brown white tip dark tip white tip white tip clypeus white clypeus black scales on tip dark with dark with yellow with broad cream- narrow white proboscis dark dark dark dark dark ring at middle dark brown dark tip colored ring (sometimes at middle absent) brown with a dark with dark with dark with brown with yellow with 2 dark brown dark with brown with broad golden golden white lyre- many lines of large with a median scutum white median golden- incomplete scales; paler scales; paler stripe of white shaped gold & white posterior stripe brown scales white median scales on scales on or gold scales pattern scales black spots stripe margin margin (also on head) brown with a dark with dark with brown with yellow with brown with dark with dark with dark with few patches thorax patches of patches of patches of dark spot patches of narrow white patches of patches of of whitish white scales white scales white scales near spiracle white scales scales white scales white scales scales dark with dark with dark with dark with dark with dark with white basal dark with yellow with basal white basal dark with bands & lateral abdomen narrow white narrow white bands shaped narrow white dark apical triangular white basal median triangular basal bands basal bands like an basal bands patches -

Mosquito Abundance in a Dirofilaria Immitis Hotspot in the Eastern State

Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 18 (2019) 100320 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vprsr Original article Mosquito abundance in a Dirofilaria immitis hotspot in the eastern state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil T ⁎ Alexandre José Rodrigues Bendasa, , Aline Serricella Brancoa, Bruno Ricardo Soares Alberigi da Silvab, Jonimar Pereira Paivaa,1, Marcia Gonçalves Nobre de Mirandaa, Flavya Mendes-de-Almeidac, Norma Vollmer Labarthed a Discente do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Medicina Veterinária, Faculdade de Veterinária, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Av. Alm. Ary Parreiras, 507 - Icaraí, Niterói, RJ 24220-000, Brazil b Discente do Curso de Medicina Veterinária, Faculdade de Veterinária, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Av. Alm. Ary Parreiras, 507 - Icaraí, Niterói, RJ 24220-000, Brazil c Departamento de Patologia e Clínica Veterinária, Faculdade de Veterinária, Faculdade de Veterinária, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Av. Alm. Ary Parreiras, 507 - Icaraí, Niterói, RJ 24220-000, Brazil d Programa de Pós-Graduação em Medicina Veterinária, Faculdade de Veterinária, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Av. Alm. Ary Parreiras, 507 - Icaraí, Niterói, RJ 24220-000, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Coastal lowlands in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, support high numbers of heartworm-infected dogs. Heartworm Microfilariae of heartworm need to be ingested by a potencial mosquito vector in order to develop into infective Mosquito-borne parasite larvae and infect a new host. Ochlerotatus taeniorhynchus and Ochlerotatus scapularis are the primary vector Mosquito vector species in the coastal lowlands of metropolitan Rio de Janeiro; thus, the aim of this study was to investigate whether these two species were abundant enough at the heartworm hotspot in the eastern area of the state to be important to the local parasite's life cycle. -

The Taxonomic History of Ochlerotatus Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891 (Diptera: Culicidae)

insects Article The Taxonomic History of Ochlerotatus Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891 (Diptera: Culicidae) Lílian Ferreira de Freitas * and Lyric C. Bartholomay Department of Pathobiological Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Mosquitoes are an extremely diverse group of aquatic insects, distributed over all continents except Antarctica. The mosquitoes belonging to the subgenus called Ochlerotatus, as understood by Reinert et al., comprise a group of several species which are endemic to the Americas, some of which are important vectors of human and animal pathogens. However, this group is characteristically undefined, i.e., no sets of characters define the group, and this presents a major challenge for the understanding of the evolutionary tree of the mosquitoes. This work underscores and contextualizes the complex taxonomic history of the group, reveals the major challenges we face in order to resolve the definition of this group, and presents a path forward for its successful revision. Abstract: A review of all taxonomic actions within the subgenus Ochlerotatus Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891 (Diptera: Culicidae) sensu Reinert et al. (2008) is provided. In particular, the complex historical taxo- nomic treatment of the type species of this group is dissected and explained in detail. Additionally, current challenges with the definition of the subgenus and its constituents are discussed, as are the requisite steps for a successful revision of the taxon. Going forward, we conclude that a taxonomic Citation: Ferreira de Freitas, L.; revision of the species should include a neotype designation for Ochlerotatus scapularis (Rondani, Bartholomay, L.C.