Kalmar Konstmuseum Bita Razavi Same Song, New Songline 2016 Photo by Jaakko Karhunen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Testimony of the Hoofprints: Danish Legends About the Medieval Union Queen Margrethe

John Lindow 2021: The Testimony of the Hoofprints: Danish Legends about the Medieval Union Queen Margrethe. Ethnologia Europaea 51(1): 137–155. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/ee.1899 The Testimony of the Hoofprints Danish Legends about the Medieval Union Queen Margrethe John Lindow, University of California, Berkeley, United States, [email protected] Barbro Klein’s “The Testimony of the Button” is still, fifty years after it appeared, a fundamental study of legends and legend scholarship. Inspired by Klein’s article, I analyze legends about “lord and lady” Margrethe (1353–1412), who reigned for decades as the effective ruler of the medieval union of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Proceeding through various groups of related legends, I show how these legends were adapted to Margrethe’s anomalous status as a female war leader, including their cross-fertilization with robber legends and the use of a ruse usually associated with male protagonists. This article ends by indicating the importance of place within history as articulated in legends. Ethnologia Europaea is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. © 2021 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. OPEN ACCESS 138 “The Testimony of the Button”: Legend and History Barbro Klein’s “The Testimony of the Button” (1971) remains an important landmark in legend studies. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities. -

A Danish Museum Art Library: the Danish Museum of Decorative Art Library*

INSPEL 33(1999)4, pp. 229-235 A DANISH MUSEUM ART LIBRARY: THE DANISH MUSEUM OF DECORATIVE ART LIBRARY* By Anja Lollesgaard Denmark’s library system Most libraries in Denmark are public, or provide public access. The two main categories are the public, local municipal libraries, and the public governmental research libraries. Besides these, there is a group of special and private libraries. The public municipal libraries are financed by the municipal government. The research libraries are financed by their parent institution; in the case of the art libraries, that is, ultimately, the Ministry of Culture. Most libraries are part of the Danish library system, that is the official library network of municipal and governmental libraries, and they profit from and contribute to the library system as a whole. The Danish library system is founded on an extensive use of inter-library lending, deriving from the democratic principle that any citizen anywhere in the country can borrow any particular book through the local public library, free of charge, never mind where, or in which library the book is held. Some research libraries, the national main subject libraries, are obliged to cover a certain subject by acquiring the most important scholarly publications, for the benefit not only of its own users but also for the entire Danish library system. Danish art libraries Art libraries in Denmark mostly fall into one of two categories: art departments in public libraries, and research libraries attached to colleges, universities, and museums. Danish art museum libraries In general art museum libraries are research libraries. Primarily they serve the curatorial staff in their scholarly work of documenting artefacts and art historical * Paper presented at the Art Library Conference Moscow –St. -

Britain's Hype for British Hygge

Scandinavica Vol 57 No 2 2018 What the Hygge? Britain’s Hype for British Hygge Ellen Kythor UCL Abstract Since late 2016, some middle-class Brits have been wearing Nordic- patterned leg warmers and Hygge-branded headbands while practising yoga in candlelight and sipping ‘Hoogly’ tea. Publishers in London isolated hygge as an appealing topic for a glut of non-fiction books published in time for Christmas 2016. This article elucidates the origins of this British enthusiasm for consuming a particular aspect of ostensibly Danish culture. It is argued that British hype for hygge is an extension of the early twenty-first century’s Nordic Noir publishing and marketing craze, but additionally that the concept captured the imaginations of journalists, businesses, and consumers as a fitting label for activities and products of which a particular section of the culturally white-British middle-classes were already partaking. Keywords Hygge, United Kingdom, white culture, Nordic Noir, publishing, cultural studies 68 Scandinavica Vol 57 No 2 2018 A December 2015 print advertisement in The Guardian for Arrow Films’ The Bridge DVDs reads: ‘Gettin’ Hygge With It!’, undoubtedly a play on the phrase from 1990s pop music hit ‘Gettin’ Jiggy Wit It’ (HMV ad 2015). Arrow Films’ Marketing Director Jon Sadler perceived the marketing enthusiasm for hygge¹ that hit Britain a year later with slight envy: ‘we’ve been talking about hygge for several years, it’s not a new thing for us [...] it’s a surprise it’s so big all of a sudden’ (Sadler 2017). Arrow Films was a year too early in its attempt to use hygge as a marketing trope. -

Learning from Scandinavia's Game of Thrones

Learning from Scandinavia’s By John Bechtel, Freelance Writerr either heritage nor history are boring, arcane subjects best suited for Heritage is about memories and identities; it seductively promises to aging seniors with nothing better to do than take dreamy trips down answer the question, where do I belong? Heritage is about geography and nostalgia lane. The only thing that can be said to be boring about topography and landscapes of the familiar; it is about emotional attachments to history from time to time is its teachers, who fail to communicate that history land and language and places; it is about our personal history and experiences does in fact repeat itself, its lessons lost upon successive generations who with such places and things, especially from an early age. But our attitudes and cannot remember yesteryear’s unkept political promises and failed ideologies. longings are also affected by others, outsiders, who may visit but who never lived it, who have other memories of other places. Both the insider’s viewpoint History is a living art; what we do, think, and act out today is tomorrow’s and the tourist’s perceptions can be valuable, because there is a certain amount history. How can that be boring? History is about taking nothing for granted, of mythmaking and whitewashing in all heritage stories. To truly benefit making no assumptions about the present or the future. History is an antidote from our heritage, we need to do more than romanticize the past. We need to to overconfidence by today’s ideologues. History is about insatiable curiosity experience it as closely as possible to the way it was to live it, not just by the about how we got to where we are, and the interplay of ideas, people—human elites of the day, but at all levels of society. -

New Nordic Cuisine Best Restaurant in the World Bocuse D'or

English // A culinary revolution highlighting local foods and combating uniform- ity has been enhancing the Taste of Denmark over the past decade. The perspec- tives of this trend are useful to everyone – in private households and catering kitchens alike. Nordic chefs use delicious tastes and environmental sustainability to combat unwholesome foods and obesity. www.denmarkspecial.dk At the same time, Danish designers continue to produce and develop furniture, tables and utensils which make any meal a holistic experience. Learn more about New Nordic Cuisine and be inspired by the ingredients, produce, restaurants and quality design for your dining experience. FOOD & DESIGN is a visual appetiser for what’s cooking in Denmark right now. Français // Une révolution culinaire axée sur les ingrédients locaux et opposée à une uniformisation a, ces 10 dernières années, remis au goût du jour les saveurs du Danemark. Cette évolution ouvre des perspectives à la disposition de tous – qu’il s’agisse de la cuisine privée ou de la cuisine à plus grande échelle. Les chefs nordiques mettent en avant les saveurs et l’environnement contre la mauvaise santé et le surpoids. Parallèlement, les designers danois ont maintenu et développé des meubles, tables et ustensiles qui font du repas une expérience d’ensemble agréable. Découvrez la nouvelle cuisine nordique et puisez l’inspiration pour vos repas dans les matières premières, les restaurants et le bon design. FOOD & DESIGN est une mise en bouche visuelle de ce qui se passe actuellement côté cuisine au Danemark. Food & Design is co-financed by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, The Trade Council What’s cooking in Denmark? New Nordic Cuisine Bocuse d’Or Playing among the stars Issue #9 2011 denmark Printed in Denmark EUR 10.00 // USD 13.00 Best restaurant special NZD 17.50 // AUD 13.50 ISBN No. -

“To Establish a Free and Open Forum”: a Memoir of the Founding of the Grundtvig Society

“To establish a free and open forum”: A memoir of the founding of the Grundtvig Society By S. A. J. Bradley With the passing of William Michelsen (b. 1913) in October 2001 died the last of the founding fathers of Grundtvig-Selskabet af 8. september 1947 [The Grundtvig Society of 8 September 1947] and of Grundtvig- Studier [Grundtvig Studies] the Society’s year-book.1 It was an appropriate time to recall, indeed to honour, the vision and the enthusiasm of that small group of Grundtvig-scholars - some very reverend and others just a touch irreverent, from several different academic disciplines and callings but all linked by their active interest in Grundtvig - who gathered in the bishop’s residence at Ribe in September 1947, to see what might come out of a cross-disciplinary discussion of their common subject. Only two years after the trauma of world war and the German occupation of Denmark, and amid all the post-war uncertainties, they talked of Grundtvig through the autumn night until, as the clock struck midnight and heralded Grundtvig’s birthday, 8 September, they formally resolved to establish a society that would serve as a free and open forum for the advancement of Grundtvig studies. The biographies of the principal names involved - who were not only theologians and educators but also historians and, conspicuously, literary scholars concerned with Grundtvig the poet - and the story of this post-war burgeoning of the scholarly reevaluation of Grundtvig’s achievements, legacy and significance, form a remarkable testimony to the integration of the Grundtvig inheritance in the mainstream of Danish life in almost all its departments, both before and after the watershed of the Second World War. -

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek the Danish National Art Library

Digitaliseret af / Digitised by Danmarks Kunstbibliotek The Danish National Art Library København / Copenhagen For oplysninger om ophavsret og brugerrettigheder, se venligst www.kunstbib.dk For information on copyright and user rights, please consult www.kunstbib.dk D 53.683 The Ehrich Galleries GDlö ilaøtrrø” (Exclusively) Danmarks Kunstbibliotek Examples French SpanS^^ Flemish Dutch PAINTINGS 463 and 465 Fifth Avenue At Fortieth Street N E W YO R K C IT Y Special Attention Given to the Expertising, Restoration and Framing o f “ (®li fHastrrii” EXHIBITION of CONTEMPORARY SCANDINAVIAN ART Held under the auspices of the AMERICAN-SCANDINAVIAN SOCIETY Introduction and Biographical Notes By CHRISTIAN BRINTON With the collaboration of Director KARL MADSEN Director JENS THUS, and CARL G. LAURIN The American Art Galleries New York December tenth to twenty-fifth inclusive 1912 SCANDINAVIAN ART EXHIBITION Under the Gracious Patronage of HIS MAJESTY GUSTAV V King of Sweden HIS MAJESTY CHRISTIAN X Copyright, 1912 King of Denmark By Christian Brinton [ First Impression HIS MAJESTY HAAKON VII 6,000 Copies King of Norway Held by the American-Scandinavian Society t 1912-1913 in NEW YORK, BUFFALO, TOLEDO, CHICAGO, AND BOSTON Redfield Brothers, Inc. New York INTRODUCTORY NOTE h e A m e r i c a n -Scandinavian So c ie t y was estab T lished primarily to cultivate closer relations be tween the people of the United States of America and the leading Scandinavian countries, to strengthen the bonds between Scandinavian Americans, and to advance the know ledge of Scandinavian culture among the American pub lic, particularly among the descendants of Scandinavians. -

Danish Sixties Avant-Garde and American Minimal Art Max Ipsen

Danish Sixties Avant-Garde and American Minimal Art Max Ipsen “Act so that there is no use in a centre”.1 Gertrude Stein Denmark is peripheral in the history of minimalism in the arts. In an international perspective Danish artists made almost no contributions to minimalism, according to art historians. But the fact is that Danish artists made minimalist works of art, and they did it very early. Art historians tend to describe minimal art as an entirely American phenomenon. America is the centre, Europe the periphery that lagged behind the centre, imitating American art. I will try to query this view with examples from Danish minimalism. I will discuss minimalist tendencies in Danish art and literature in the 1960s, and I will examine whether one can claim that Danish artists were influenced by American minimal art. Empirical minimal art The last question first. Were Danish artists and writers influenced by American minimal art? The straight answer is no. The fact is that they did not know about American minimal art when they first made works, which we today can characterize as minimal art or minimalism. Minimalism was just starting to occur in America when minimalist works of art were made in Denmark. Some Danish artists, all of them linked up with Den eksperimenterende Kunstskole (The Experimenting School of Art), or Eks-skolen as the school is most often called, in Copenhagen, were employing minimalist techniques, and they were producing what one would tend to call minimalist works of art without knowing of international minimalism. One of these artists, Peter Louis-Jensen, years later, in 1986, in an interview explained: [Minimalism] came to me empirically, by experience, whereas I think that it came by cognition to the Americans. -

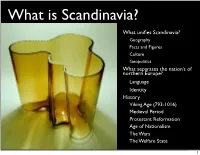

What Is Scandinavia?

What is Scandinavia? What unifies Scandinavia? Geography Facts and Figures Culture Geopolitics What separates the nation’s of northern Europe? Language Identity History Viking Age (793-1016) Medieval Period Protestant Reformation Age of Nationalism The Wars The Welfare State 1 Geography • Definining characteristics of Scandinavia’s location • Climate • Maritime access • Landmass • Forests • Not a “crossroads” • No Roman history Scandinavia on the northern margin of Europe, alongside Russia and Germany 2 Facts and Figures • Denmark • Norway • Copenhagen • Oslo • Danish • Trondheim • 5 million • Christiania • Finland • Norwegian • Helsinki • 4.5 million • Finnish/Swedish • Sweden • 5 million • Stockholm • Iceland • Göteborg • Reykjavik • Malmö • Icelandis • Swedish • 250,000 • 9 million 3 Culture • What do we mean by culture? • Organic implications • Culture as construct • “High Culture • “Anthropological culture” • Institutions as key construction sites • Unifying elements of Scandinavian culture • History • Not a part of Roman Empire • Vikings circa 800-1100 • Kalmar Union 1397-1512 • Language • Lutheran church • Constitutional Monarchies 13th-century Stavkirke, Norway • Universal welfare state 4 Geopolitics Finnish soldiers during the Continuation War, 1941-1944 • What is geopolitics? • Multiple causes for institutional (state) behavior • What relations of economics and geography together explain policy • Scandinavia on the Margins • Relatively limited sources of wealth • Small population dispersed over poor agricultural land • Location -

Reading Sample

Katharina Alsen | Annika Landmann NORDIC PAINTING THE RISE OF MODERNITY PRESTEL Munich . London . New York CONTENTS I. ART-GEOGRAPHICAL NORTH 12 P. S. Krøyer in a Prefabricated Concrete-Slab Building: New Contexts 18 The Peripheral Gaze: on the Margins of Representation 23 Constructions: the North, Scandinavia, and the Arctic II. SpACES, BORDERS, IDENTITIES 28 Transgressions: the German-Danish Border Region 32 Þingvellir in the Focal Point: the Birth of the Visual Arts in Iceland 39 Nordic and National Identities: the Faroes and Denmark 45 Identity Formation in Finland: Distorted Ideologies 51 Inner and Outer Perspectives: the Painting and Graphic Arts of the Sámi 59 Postcolonial Dispositifs: Visual Art in Greenland 64 A View of the “Foreign”: Exotic Perspectives III. THE SENSE OF SIGHT 78 Portrait and Artist Subject: between Absence and Presence 86 Studio Scenes: Staged Creativity 94 (Obscured) Visions: the Blind Eye and Introspection IV. BODY ImAGES 106 Open-Air Vitalism and Body Culture 115 Dandyism: Alternative Role Conceptions 118 Intimate Glimpses: Sensuality and Desire 124 Body Politics: Sexuality and Maternity 130 Melancholy and Mourning: the Morbid Body V. TOPOGRAPHIES 136 The Atmospheric Landscape and Romantic Nationalism 151 Artists’ Colonies from Skagen to Önningeby 163 Sublime Nature and Symbolism 166 Skyline and Cityscape: Urban Landscapes VI. InnER SpACES 173 Ideals of Dwelling: the Spatialization of an Idea of Life 179 Formations: Person and Interior 184 Faceless Space, Uncanny Emptying 190 Worlds of Things: Absence and Materiality 194 The Head in Space: Inner Life without Boundaries VII. FORM AND FORMLESSNESS 202 In Dialogue with the Avant-garde: Abstractions 215 Invisible Powers: Spirituality and Psychology in Conflict 222 Experiments with Material and Surface VIII.