Pengyuan Credit Rating (Hong Kong) Co.,Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Service Summary

COSCO SHIPPING TRANSPACIFIC SERVICE OVERVIEW Service Summary 23 SERVICE LINES cover 161 PORT PAIRS since 1st. April, 2017 * Including COSCO SHIPPING Out-Alliance Service Lines PSW/PNW/AWE SERVICE LINE OVERVIEW PSW Service Summary 12 Far-east to Southwest Coast of America Service lines Cover 61 Port Pairs CEN (COSCO)* AAC (COSCO) AAC2 (CMA+EMC) AAC3 (COSCO+WHL+PIL)** AAC4 (OOCL) Service 6 X 10000 6 X 10000 6 X 9000 6 X 8500 5 X 7800 Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB XINGANG 0 DALIAN 0 QINGDAO 0 QINGDAO 0 NINGBO 0 QINGDAO 3 LIANYUNGANG 1 SHANGHAI 2 SHANGHAI 2 SHANGHAI 1 SHANGHAI 5 SHANGHAI 4 NINGBO 4 NINGBO 3 PUSAN 4 Port Load of Port NINGBO 6 PRINCE RUPERT 17 LONG BEACH 20 LONG BEACH 18 LONG BEACH 17 LONG BEACH 16 LONG BEACH 22 SEATTLE 28 OAKLAND 23 OAKLAND 22 PUSAN 33 OAKLAND 27 DALIAN 42 TOKYO 38 QINGDAO 42 NINGBO 35 XINGANG 42 NAGOYA 39 QINGDAO 42 Port Discharge of Port *The details of all the services will be optimized further. ** COSCO SHIPPING’s Out-Alliance Service Lines PSW Service Summary 12 Far-east to Southwest Coast of America Service lines Cover 61 Port Pairs AAS (OOCL) AAS2 (CMA) AAS3 (EMC) AAS4 (EMC) Service 6 X 9000 6 X 14000 6 X 6500 6 X 7000 Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB CAI MEP 0 FUQING 0 TAIPEI 0 YANTIAN 0 SHEKOU 3 NANSHA 2 XIAMEN 3 HONG KONG 1 HONG KONG 3 HONG KONG 3 SHEKOU 4 KAOHSIUNG 3 Port of Load Port YANTIAN 4 YANTIAN 4 YANTIAN 5 TAIPEI 4 KAOHSIUNG 6 XIAMEN 6 LONG BEACH 19 LONG BEACH 20 LONG BEACH 20 LONG BEACH 18 KAOHSIUNG 38 OAKLAND 25 OAKLAND 24 OAKLAND 22 CAI MEP 42 FUQING 42 TAIPEI 42 -

Ningbo Facts

World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan 213730-00 Final | June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan Contents Page 1 Executive Summary 4 2 Introduction 10 3 Urban Resilience Methodology 13 3.1 Overview 13 3.2 Approach 14 3.3 Hazard Assessment 14 3.4 City Vulnerability Assessment 15 3.5 Spatial Assessment 17 3.6 Stakeholder Engagement 17 3.7 Local Resilience Action Plan 18 4 Ningbo Hazard Assessment 19 4.1 Hazard Map 19 4.2 Temperature 21 4.3 Precipitation 27 4.4 Droughts 31 4.5 Heat Waves 32 4.6 Tropical Cyclones 33 4.7 Floods 35 4.8 Sea Level Rise 37 4.9 Ningbo Hazard Analysis Summary 42 5 Ningbo Vulnerability Assessment 45 5.1 People 45 5.2 Infrastructure 55 5.3 Economy 69 5.4 Environment 75 5.5 Government 80 6 Gap Analysis 87 6.1 Overview 87 6.2 Natural Disaster Inventory 87 6.3 Policy and Program Inventory 89 6.4 Summary 96 7 Recommendations 97 7.1 Overview 97 7.2 People 103 7.3 Infrastructure 106 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan 7.4 Economy 112 7.5 Environment 115 7.6 Government 118 7.7 Prioritized Recommendations 122 8 Conclusions 126 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan List of Tables Table -

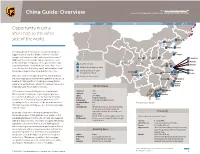

China Guide: Overview Or Call UPS International Customer Service at 1-800-782-7892

Visit ups.com/international China Guide: Overview or call UPS International Customer Service at 1-800-782-7892. GMT+ 5.5 GMT+ 6 GMT+ 7 GMT+ 8 GMT+ 8.5 Opportunity is just a short hop to the other Shenyang side of the world. Beijing Tianjin Dalian In today’s global economy, no country represents a bigger opportunity than China. Home to 1.3 billion Qingdao people and numerous cities with populations over 5 Xi’an Zhengzhou Changzhou million, China is the world’s largest exporter, as well Nantong as the third-largest importer of U.S. goods. While large Key UPS Air Hubs CHINA Nanjing Kunshan corporations have established a presence here, it is a Hefei Multiple UPS Package Facilities lesser known fact that many small- and medium-sized Shanghai American enterprises are already active here, too. UPS Air and Ocean Freight Wuxi Chengdu Hangzhou Ningbo Forwarding Locations Wuhan Suzhou Chongqing Shaoxing Have you considered expansion to the China market, UPS Aircraft Connections but new languages and unknown regulations have been Jiaxing Wenzhou a barrier to taking action? Thinking you need global Fuzhou experience and a global network to make an impression Quanzhou Xiamen internationally? No problem. Use ours. UPS in China Dongguan Guangzhou Huizhou UPS is one of the world’s largest customs brokers. Established: 1988 Foshan Employees: 6,000+ We know the ins and outs of getting your products Jiangmen Shenzhen Flights: 200+ weekly to customers in China because we have been doing Zhongshan Air Hubs: Shenzhen and Shanghai Zhuhai business there for nearly 30 years. More than 225 Delivery Fleet: 864 package vans, trailers and trucks operating facilities, two state-of-the-art hubs and over Operating Facilities: 225+ *Principal locations displayed 200 flights weekly can help you get closer to a growing Cities: 300+ customer base. -

The First Real-Estate Development by Japanese Developers in Changchun, Jilin Province, China Marubeni Coporation and Mitsubishi Jisho Residence Co., Ltd

July 18, 2013 Marubeni Corporation Mitsubishi Jisho Residence Co., Ltd. The First Real-Estate Development by Japanese Developers in Changchun, Jilin Province, China Marubeni Coporation and Mitsubishi Jisho Residence Co., Ltd. set off the Joint Development –“Changchun Jingyue Project (Tentative)” <Perspective of the project> Marubeni Corporation (“Marubeni”) and Mitsubishi Jisho Residence Co., Ltd. (“Mitsubishi Jisho Residence”), as the first Japanese developers, plan to implement a real-estate development project with Jilin Weifeng Industry Co., Ltd. (“Weifeng”), a local Chinese developer, in Changchun, China. This project, as our first project in Changchun, with an area of 130,000 square meters, is located in Changchun Jingyue National High-tech Industrial Development Zone (“Jingyue DZ”), concentrating on Town House and Residential. The Project Company, Changchun Top Chance Property Development Co., Ltd. (“Changchun Top Chance”) owned by Marubeni (40%), Weifeng (35%) and Mitsubishi Jisho Residence (25%), has started the construction for the release this coming fall. Changchun is the capital of Jilin Province, also a core city in the northeastern part of China, with a population of 7,620,000. It is administered as one of 15 sub-provincial cities which are independent and equivalent to provinces. Having a solid industrial basis including automobile manufacturing as typified by FAW (First Automotive Works) Group, along with manufacturing transportation facilities and processing agricultural products, Changchun is continuing double digit economic growth, which is higher than the national average. Jingyue DZ is a national-level development zone approved by the State Council in August, 2012, with an area of 479 square kilometers, of which about half of the area, 243 square kilometers, consists of forest and a lake. -

Spatial Heterogeneous of Ecological Vulnerability in Arid and Semi-Arid Area: a Case of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China

sustainability Article Spatial Heterogeneous of Ecological Vulnerability in Arid and Semi-Arid Area: A Case of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China Rong Li 1, Rui Han 1, Qianru Yu 1, Shuang Qi 2 and Luo Guo 1,* 1 College of the Life and Environmental Science, Minzu University of China, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] (R.L.); [email protected] (R.H.); [email protected] (Q.Y.) 2 Department of Geography, National University of Singapore; Singapore 117570, Singapore; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 April 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2020; Published: 28 May 2020 Abstract: Ecological vulnerability, as an important evaluation method reflecting regional ecological status and the degree of stability, is the key content in global change and sustainable development. Most studies mainly focus on changes of ecological vulnerability concerning the temporal trend, but rarely take arid and semi-arid areas into consideration to explore the spatial heterogeneity of the ecological vulnerability index (EVI) there. In this study, we selected the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region on the Loess Plateau of China, a typical arid and semi-arid area, as a case to investigate the spatial heterogeneity of the EVI every five years, from 1990 to 2015. Based on remote sensing data, meteorological data, and economic statistical data, this study first evaluated the temporal-spatial change of ecological vulnerability in the study area by Geo-information Tupu. Further, we explored the spatial heterogeneity of the ecological vulnerability using Getis-Ord Gi*. Results show that: (1) the regions with high ecological vulnerability are mainly concentrated in the north of the study area, which has high levels of economic growth, while the regions with low ecological vulnerability are mainly distributed in the relatively poor regions in the south of the study area. -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Supplement of Modeling Diurnal Variation of Surface PM2.5

Supplement of Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 2839–2863, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-2839-2020-supplement © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of Modeling diurnal variation of surface PM2:5 concentrations over East China with WRF-Chem: impacts from boundary-layer mixing and anthropogenic emission Qiuyan Du et al. Correspondence to: Chun Zhao ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. Supporting materials for “Modeling diurnal variation of surface PM2.5 concentration over East China with WRF-Chem: Impacts from boundary layer mixing and anthropogenic emission” Figure S1. Spatial distribution of peak diurnal index of surface PM2.5 concentrations in the four months from experiments CTL1, CTL2, and CTL3. The observations are shown as the color filled circles. The observations at the stations within one city are averaged and shown as one circle as they are too close to be shown distinctly. Figure S2. Comparison between monthly mean surface PM2.5 concentrations and diurnal index of surface PM2.5 concentrations at each observational site over the YRD region of East China (within black box of Fig. 1a) for April and October from observations and experiments CTL1, CTL2, and CTL3. Figure S3a. Relative contribution (normalized by monthly mean surface PM2.5 concentrations for each month) to surface PM2.5 concentrations every 3-hour from individual process (transport, emission, dry and wet deposition, PBL mixing, chemical production/loss) averaged over Nanjing(a) for January, April, July, and October of 2018 from experiments CTL1, CTL2, and CTL3. -

Prohibited Agreements with Huawei, ZTE Corp, Hytera, Hangzhou Hikvision, Dahua and Their Subsidiaries and Affiliates

Prohibited Agreements with Huawei, ZTE Corp, Hytera, Hangzhou Hikvision, Dahua and their Subsidiaries and Affiliates. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), 2 CFR 200.216, prohibits agreements for certain telecommunications and video surveillance services or equipment from the following companies as a substantial or essential component of any system or as critical technology as part of any system. • Huawei Technologies Company; • ZTE Corporation; • Hytera Communications Corporation; • Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Company; • Dahua Technology company; or • their subsidiaries or affiliates, Entering into agreements with these companies, their subsidiaries or affiliates (listed below) for telecommunications equipment and/or services is prohibited, as doing so could place the university at risk of losing federal grants and contracts. Identified subsidiaries/affiliates of Huawei Technologies Company Source: Business databases, Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd., 2017 Annual Report • Amartus, SDN Software Technology and Team • Beijing Huawei Digital Technologies, Co. Ltd. • Caliopa NV • Centre for Integrated Photonics Ltd. • Chinasoft International Technology Services Ltd. • FutureWei Technologies, Inc. • HexaTier Ltd. • HiSilicon Optoelectronics Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device (Dongguan) Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device (Hong Kong) Co., Ltd. • Huawei Enterprise USA, Inc. • Huawei Global Finance (UK) Ltd. • Huawei International Co. Ltd. • Huawei Machine Co., Ltd. • Huawei Marine • Huawei North America • Huawei Software Technologies, Co., Ltd. • Huawei Symantec Technologies Co., Ltd. • Huawei Tech Investment Co., Ltd. • Huawei Technical Service Co. Ltd. • Huawei Technologies Cooperative U.A. • Huawei Technologies Germany GmbH • Huawei Technologies Japan K.K. • Huawei Technologies South Africa Pty Ltd. • Huawei Technologies (Thailand) Co. • iSoftStone Technology Service Co., Ltd. • JV “Broadband Solutions” LLC • M4S N.V. • Proven Honor Capital Limited • PT Huawei Tech Investment • Shanghai Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. -

Changsha:Gateway to Inland China

0 ︱Changsha: Gateway to Inland China Changsha Gateway to Inland China Changsha Investment Environment Report 2013 0 1 ︱ Changsha: Gateway to Inland China Changsha Changsha is a central link between the coastal areas and inland China ■ Changsha is the capital as well as the economic, political and cultural centre of Hunan province. It is also one of the largest cities in central China(a) ■ Changsha is located at the intersection of three major national high- speed railways: Beijing-Guangzhou railway, Shanghai-Kunming railway (to commence in 2014) and Chongqing-Xiamen railway (scheduled to start construction before 2016) ■ As one of China’s 17 major regional logistics hubs, Changsha offers convenient access to China’s coastal areas; Hong Kong is reachable by a 1.5-hour flight or a 3-hour ride by CRH (China Railways High-speed) Changsha is well connected to inland China and the world economy(b) Domestic trade (total retail Total value of imports and CNY 245.5 billion USD 8.7 billion sales of consumer goods) exports Value of foreign direct Total value of logistics goods CNY 2 trillion, 19.3% investment and y-o-y USD 3.0 billion, 14.4% and y-o-y growth rate growth rate Total number of domestic Number of Fortune 500 79.9 million, 34.7% tourists and y-o-y growth rate companies with direct 49 investment in Changsha Notes: (a) Central China area includes Hunan Province, Hubei Province, Jiangxi Province, Anhui Province, Henan Province and Shanxi Province (b) Figures come from 2012 statistics Sources: Changsha Bureau of Commerce; Changsha 2012 National Economic and Social Development Report © 2013 KPMG Advisory (China) Limited, a wholly foreign owned enterprise in China and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative ("KPMG International"), a Swiss entity. -

Association Between Blood Glucose Levels in Insulin Therapy And

Association between blood glucose levels in insulin therapy and Glasgow Outcome Score in patients with traumatic brain injury: secondary analysis of a randomized trial Tao Yuan Department of Neurosurgery, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Hongyu He Department of Neurosurgery, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Yuepeng Liu Center for clinical research and translational medicine, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Jianwei Wang Department of Neurosurgery, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Xin Kang Department of Neurosurgery, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Guanghui Fu Department of Neurosurgery, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Fangfang Xie Department of Neurosurgery, the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University Aimin Li Lianyungang No 1 People's Hospital Jun Chen Lianyungang No 1 People's Hospital Wen-xue Wang ( [email protected] ) Department of Neurosurgery,the aliated Lianyungang Oriental Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9865-6811 Research Article Keywords: Traumatic brain injuries, Glasgow Outcome Score, hyperglycaemia, insulin therapy Posted Date: June 14th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-615839/v1 Page 1/18 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/18 Abstract Background: Too high or low blood glucose levels after traumatic brain injury (TBI) negatively affect the prognosis of patients with TBI. This study aimed to examine the relationship between different levels of blood glucose in insulin therapy and Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS) in patients with TBI. -

R515-0025-Xf-0107.Pdf

February 22, 2019 Mizuho Bank, Ltd. Mizuho concludes memorandum of understanding for business cooperation with the Suzhou Xiangcheng Economic Development Zone Administrative Committee in China’s Jiangsu province Mizuho Bank, Ltd. (President & CEO: Koji Fujiwara) and our China-based subsidiary, Mizuho Bank (China), Ltd., today signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for business cooperation with the Suzhou Xiangcheng Economic Development Zone Administrative Committee in China’s Jiangsu province, for the purpose of promoting investment in the region and developing policy aimed at attracting foreign firms. The Xiangcheng district of Suzhou is centrally located within one of China’s three major economic zones, the Yangtze River Delta. Xiangcheng is often referred to as the “only intersection of the Yangtze River Delta” and this geographically advantageous location makes it a key target for transportation infrastructure development, including a high-speed railway currently being constructed to connect the cities of Nantong, Suzhou, Jiaxing, and Ningbo. The Economic Development Zone was established in 2002 and is a national level development zone. A broad range of industries are concentrated in the zone, including auto parts, precision machinery, and information technology, and further growth is expected going forward. Currently, a China-Japan smart manufacturing innovation industrial park is being established with the aim of creating a hub for smart manufacturing. This industrial park will be designed to attract Japanese companies specializing in advanced technologies in fields such as next-generation information technology, robots, and new materials. Based on this MOU, Mizuho will provide a range of support including providing advice on how to further develop and attract corporations to the Suzhou Xiangcheng Economic Development Zone, and holding investment seminars. -

This Is Northeast China Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Roseanne Freese Prepared By: Roseanne Freese

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 12/30/2016 GAIN Report Number: SH0002 China - Peoples Republic of Post: Shenyang This is Northeast China Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Roseanne Freese Prepared By: Roseanne Freese Report Highlights: Home to winter sports, ski resorts, and ancient Manchurian towns, Dongbei or Northeastern China is home to 110 million people. With a down-home friendliness resonant of the U.S. Midwest, Dongbei’s denizens are the largest buyer of U.S. soybeans and are China’s largest consumers of beef and lamb. Dongbei companies, processors and distributors are looking for U.S. products. Dongbei importers are seeking consumer-ready products such as red wine, sports beverages, and chocolate. Processors and distributors are looking for U.S. hardwoods, potato starch, and aquatic products. Liaoning Province is also set to open China’s seventh free trade zone in 2018. If selling to Dongbei interests you, read on! General Information: This report provides trends, statistics, and recommendations for selling to Northeast China, a market of 110 million people. 1 This is Northeast China: Come See and Come Sell! Home to winter sports, ski resorts, and ancient Manchurian towns, Dongbei or Northeastern China is home to 110 million people. With a down-home friendliness resonant of the U.S. Midwest, Dongbei’s denizens are the largest buyer of U.S. soybeans and are China’s largest consumers of beef and lamb. Dongbei companies, processors and distributors are looking for U.S.