Strategies for Reducing Employee Stress and Increasing Employee Engagement Kumar G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occupational Stress, Physical Wellness and Productivity Barometer at Workplace

ISSN: 2278-3369 International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics Available online at: www.managementjournal.info RESEARCH ARTICLE Occupational Stress, Physical Wellness and Productivity Barometer at Workplace Jyotirmayee Choudhury Dept of Business Administration Utkal University Vanivihar, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. Abstract: The paper is a conceptual one to understand the relationship between occupational stress, physical wellbeing and productivity barometer such as burnout, illness, labour turnover and absenteeism. The accumulated unpleasant emotional and psychological feelings ascend out of occupational stress impacts the physical and mental wellness of an employee which ultimately depreciates his/ her productivity barometer. The present paper is a conceptual frame work to understand the concept stress, occupational stress and individual’s appraisal of it in his/her work environment. The research work analyses occupational stress as more of a sort of individual generated which rises out of individual’s assessment of the stressors of work life. The objective of the research work is to study on occupational stress, physical and psychological wellbeing and productivity barometer. The research article attempts to suggest in promoting health philosophy and physical wellness programme in organisation’s work culture and environment through individual initiated interventions and organisation policy to put a control on occupational stress in order to check the alarming signal of productivity barometer. Keywords: Occupational Stress, Physical Wellbeing, Productivity Barometer, Quality of Work Life and Quality of Life. Article Received: 01 August 2019 Revised: 10 August 2019 Accepted: 22 August 20198 Introduction Stress in general and organizational stress in inevitable feature of most contemporary particular is a universal and frequently workplaces. -

Engaging the Workforce Getting Past Once-And-Done Measurement Surveys to Achieve Always-On Listening and Meaningful Response

Engaging the workforce Getting past once-and-done measurement surveys to achieve always-on listening and meaningful response Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives / Engaging the workforce What is employee engagement? Organizations are increasingly talking about engagement, but not everyone is defining and measuring it in the same way. Engagement typically refers to an employee’s job satisfaction, loyalty, and inclination to expend discretionary effort toward organizational goals.1 It predicts individual performance and operates at the most fundamental levels of the organization —individual and line—where the most meaningful impact can be made. Workplace culture is related, though operates on a different level. Culture is a system of values, beliefs, and behaviors that shape how real work gets done within an organization. It predicts company performance, and is shaped and cultivated at the most senior levels of the organization. 1 Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives / Engaging the workforce The vast majority of executives responding to our Global Human Capital Trends survey rated engagement as a priority for their companies. More than executives rated engagement as important or very important.2 8 in10 But company actions regarding engagement don’t always support that level of importance. Just 64% And of respondents say they are measuring employee one in five engagement once a year.3 (18%) said their companies don’t formally measure employee engagement at all.4 As the workforce and its expectations about work evolve rapidly, employers should start treating engagement as the business-critical issue it is. 1 Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives / Engaging the workforce Why does employee engagement matter ? Engagement is critical because it is directly linked to business outcomes. -

Employee Onboarding

Strategic Onboarding: The Effects on Productivity, Engagement, & Turnover By: Lisa Reed, MBA, SPHR Onboarding Defined A systematic and comprehensive approach to integrating a new employee with an employer and its culture, while also ensuring the employee is provided with the tools and information necessary to becoming a productive member of the team (1). How Important is Onboarding? 43% of employees state the opportunity for advancement was the key factor in deciding whether or not to stay with an organization, and the onboarding process, or lack thereof, was a main factor in determining advancement potential within a company (2). EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY What is Employee Productivity? An assessment of the efficiency of a worker or group of workers, which is typically compared to averages, is referred to as employee productivity (3). Costs of Employee Unproductivity More than $37 billion dollars annually is spent by organizations in the US to keep unproductive employee in jobs they do not understand (4). What Effect Does Strategic Onboarding Have On Employee Productivity? Only 49% of new employees without formal onboarding meet their first performance milestone (5). In contrast, 77% of employees who are provided with a formal onboarding process meet first performance milestones (6). Employee performance can increase by 11% with an effective onboarding process, which can also be linked to a 20% increase in an employee’s discretionary effort (7). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT What is Employee Engagement? Employee engagement describes the way employees show a logical and emotional commitment to their work, team, and organization, which in turn drives their discretionary effort. Costs of Employee Disengagement Actively disengaged employees are more likely to steal, miss work, and negatively influence other workers and cost the United States up to $550 billion annually in lost resources and productivity (8). -

Data Sheet: Oracle Recruiting Cloud

Oracle Recruiting Finding the best talent, hiring them quickly and onboarding them efficiently, can be difficult in today’s competitive environment. Oracle Recruiting (part of Oracle Cloud HCM) addresses these common challenges of recruiting and takes this process into the modern era by leveraging a data-driven approach and a mobile user interface (UI) to Key features source and engage both internal and external • Requisition management • Career page design templates candidates, and apply business insights across • Mobile-responsive UI all of HCM for better hiring decisions. • Extensible branding and multimedia support • Job search and discovery INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY TO KEEP CANDIDATES AT • Candidate pools THE CENTER OF THE RECRUITING PROCESS • Adaptive intelligence Savvy organizations use technology to stay ahead of the competition when it comes • Native recruiting to attracting and retaining top talent. HR leaders are being tasked with broadening • End-to-end sourcing, recruiting, their approach to Human Capital Management, incorporating concepts and practices and offers that were once the primary domain of marketing, legal, or chief executives. The • Unified architecture and tooling practice of HR is also transforming from being a mere cost center to a value • Multichannel sourcing generator, driving business growth through holistic talent development. HR is evolving to increasingly leverage technology to improve efficiency and provide • Conversational interactions via insight into an organization’s most valuable source of productivity. Organizations use digital assistant this insight to help leaders understand success parameters and their organization’s • Proven third-party extensions talent capabilities. • Advanced reporting and analytics Oracle Recruiting is a new recruiting solution delivered natively as part of Oracle • Unified self-service interface Cloud HCM. -

Leading Remote Teams Provided By: Taggart Insurance

Leading Remote Teams Provided by: Taggart Insurance This HR Toolkit is not intended to be exhaustive nor should any discussion or opinions be construed as legal advice. Readers should contact legal counsel for legal advice. © 2020 Zywave, Inc. All rights reserved. Leading Remote Teams | Provided by: Taggart Insurance Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................4 Remote Work Planning ................................................................................................5 Schedules .....................................................................................................5 Technology ....................................................................................................5 Employee Workstation ..................................................................................5 Policies ..........................................................................................................6 Interviewing and Onboarding .......................................................................6 Virtual Interviewing ................................................................6 Remote Onboarding ..............................................................7 Company Culture in the Remote Workplace ...............................................................9 What Is Company Culture? ..........................................................................9 Strong Company Culture.............................................................................. -

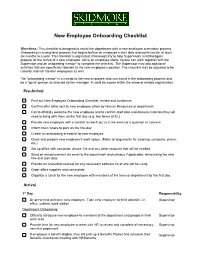

New Employee Onboarding Checklist

New Employee Onboarding Checklist Directions: This checklist is designed to assist the department with a new employee orientation process. Onboarding is a long-term process that begins before an employee’s start date and continues for at least six months to a year. This checklist is organized chronologically to help Supervisors and Managers prepare for the arrival of a new employee. Once an employee starts, he/she can work together with the Supervisor and an onboarding mentor* to complete the checklist. The Supervisor may add additional activities that are specifically relevant to the new employee’s position. The checklist may be adjusted to be used for internal transfer employees as well. *An "onboarding mentor" is a mentor to the new employee who can assist in the onboarding process and be a “go-to” person as directed by the manager. It could be a peer within the same or related organization. Pre-Arrival Print out New Employee Onboarding Checklist, review and customize Confirm offer letter sent to new employee either by Human Resources or department Call to officially welcome the new employee and to confirm start date and discuss materials they will need to bring with them on the first day (e.g. two forms of ID.) Provide new employee with a contact to reach out to in the event of a question or concern Inform them where to park on the first day Create an onboarding schedule for new employee Clean and prepare new employee's work space. (Make arrangements for cleaning, computer, phone, etc.) Set up office with computer, phone, file and any other resource that will be needed Send an announcement via email to the department and campus if applicable, announcing the new hire and start date Provide an instruction manual for any necessary software he or she will be using Order office supplies and name plate Organize a lunch for the new employee with members of the team or department for the first day Arrival 1st Day Responsibility Be present to welcome new employee. -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Relationship Between Telecommuting and Occupational Stressors of Nonprofit Professionals A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Public Administration in Non-Profit Sector Management By Stephanie Mendoza August 2020 Copyright by Stephanie Mendoza 2020 ii The graduate project of Stephanie Mendoza is approved: _______________________________________ __________ Dr. Elizabeth A. Trebow Date _______________________________________ ___________ Dr. Sarmistha R. Majumdar Date _______________________________________ ___________ Dr. Judith A. DeBonis, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude to my Graduate Project committee: Dr. Judith A DeBonis, Committee Chair, Dr. Elizabeth A. Trebow, and Dr. Sarmistha R. Majumdar. To Dr. DeBonis, thank you for your patience, guidance, and constant motivation. I am grateful for your dedication to my success and the advocacy you demonstrated for our cohort. To Dr. Ann Marie Yamada, thank you for the timely advice, insight, and reassurance. To my family and friends, thank you for supporting my education over the years. Your words of encouragement will resonate with me, always. iv Table of Contents Copyright Page ii Signature Page iii Acknowledgements iv Abstract vii Introduction 1 Purpose of the Present Study 1 Aims and Objectives 1 Background 3 Terms and Concepts 3 Historical Context 3 Prevalence 4 Literature Review 5 Occupational Stress 5 Flexible -

Employees' Reactions to Their Own Gossip About Highly

BITING THE HAND THAT FEEDS YOU: EMPLOYEES’ REACTIONS TO THEIR OWN GOSSIP ABOUT HIGHLY (UN)SUPPORTIVE SUPERVISORS By JULENA MARIE BONNER Bachelor of Arts in Business Management and Leadership Southern Virginia University Buena Vista, VA 2007 Master of Business Administration Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2016 BITING THE HAND THAT FEEDS YOU: EMPLOYEES’ REACTIONS TO THEIR OWN GOSSIP ABOUT HIGHLY (UN)SUPPORTIVE SUPERVISORS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Rebecca L. Greenbaum Dissertation Adviser Dr. Debra L. Nelson Dr. Cynthia S. Wang Dr. Isaac J. Washburn ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The road to completing this degree and dissertation has been a long, bumpy one, with plenty of ups and downs. I wish to express my gratitude to those who have helped me along the way. Those who provided me with words of encouragement and support, those who talked me down from the ledge when the bumps seemed too daunting, and those who helped smooth the path by taking time to teach and guide me. I will forever be grateful for my family, friends, and the OSU faculty and doctoral students who provided me with endless amounts of support and guidance. I would like to especially acknowledge my dissertation chair, Rebecca Greenbaum, who has been a wonderful mentor and friend. I look up to her in so many ways, and am grateful for the time she has taken to help me grow and develop. I want to thank her for her patience, expertise, guidance, support, feedback, and encouragement over the years. -

Incivility, Bullying, and Workplace Violence

AMERICAN NURSES ASSOCIATION POSITION STATEMENT ON INCIVILITY, BULLYING, AND WORKPLACE VIOLENCE Effective Date: July 22, 2015 Status: New Position Statement Written By: Professional Issues Panel on Incivility, Bullying and Workplace Violence Adopted By: ANA Board of Directors I. PURPOSE This statement articulates the American Nurses Association (ANA) position with regard to individual and shared roles and responsibilities of registered nurses (RNs) and employers to create and sustain a culture of respect, which is free of incivility, bullying, and workplace violence. RNs and employers across the health care continuum, including academia, have an ethical, moral, and legal responsibility to create a healthy and safe work environment for RNs and all members of the health care team, health care consumers, families, and communities. II. STATEMENT OF ANA POSITION ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements states that nurses are required to “create an ethical environment and culture of civility and kindness, treating colleagues, coworkers, employees, students, and others with dignity and respect” (ANA, 2015a, p. 4). Similarly, nurses must be afforded the same level of respect and dignity as others. Thus, the nursing profession will no longer tolerate violence of any kind from any source. All RNs and employers in all settings, including practice, academia, and research, must collaborate to create a culture of respect that is free of incivility, bullying, and workplace violence. Evidence-based best practices must be implemented to prevent and mitigate incivility, bullying, and workplace violence; to promote the health, safety, and wellness of RNs; and to ensure optimal outcomes across the health care continuum. -

Relationship Between Job Stress and Workplace Incivility Regarding to the Moderating Role of Psychological Capital

Journal of Fundamentals Mashhad University Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences of Mental Health of Medical Sciences Research Center lagigirO Article Relationship between job stress and workplace incivility regarding to the moderating role of psychological capital *Seyed Esmaeil Hashemi1; Sahar Savadkouhi2; Abdolzahra Naami3; Kioumars Beshlideh1 1Associate professor of psychology, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran 2MA. student in industrial and organizational psychology, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran 3Professor of psychology, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran Abstract Introduction: The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship of job stress and workplace incivility behaviors considering the moderating role of psychological capital (resiliency, optimism, hope, and efficacy). Materials and Methods: Participants of this descriptive-analytical study were 297 employees of Khozestan Regional Electrical Company in Ahvaz at year of 2016 were selected by stratified randomized sampling method. These participants completed the job stress, workplace incivility behaviors and psychological capital questionnaires. Pearson correlation and hierarchical regression analyses were used to analysis. Results: Findings indicated that job stress was negatively related to workplace incivility (P=0.008) and resiliency moderated the relationship of job stress with workplace incivility (P=0.04). Moreover optimism, hope, and self-efficacy not moderated relationship of job stress with workplace incivility. Conclusion: The results showed that the relationship between job stress and workplace incivility in high resilient employees is weaker than the relationship between these two variables in employees with low resiliency. Keywords: Job stress, Psychological capital, Resilience Please cite this paper as: Hashemi SE, Savadkouhi S, Naami A, Beshlideh K. Relationship between job stress and workplace incivility regarding to the moderating role of psychological capital. -

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace Background A discrimination-free workplace is one in which employees are attracted, recruited, assigned to work, provided with training and development, promoted and remunerated on the basis of their capabilities. It signals that no distinction, exclusion or preference relating to an individual’s employment is made on grounds other than the ability or potential ability of an individual to meet required job needs. Discrimination-free means equal opportunity for all, irrespective of non-work-related personal characteristics. Further, it means actively advancing practices that promote equity by, for example, assuring inclusive selection criteria to more fully reach qualified persons. Discrimination in any form is harmful to society, individuals, and the conduct of business. By definition, discrimination prevents individuals from realizing their human rights and from fully and productively participating in society and/or business activity. The achievement of a prosperous society depends on all individuals being treated with dignity and respect. The achievement of sustainable business equally depends on individuals attaining employment in a workplace that values them and their unique qualities. Relevance As the largest and most broadly based healthcare company in the world, Johnson & Johnson has a considerable impact on the lives of many individuals whom we directly employ, and this includes providing a workplace in which employees can feel valued, safe and free from discrimination. We believe that fostering an open and inclusive work environment, in which we value contributions from individuals of all backgrounds and experiences, is not only the right thing to do, it gives us the best chance of being able to work together to advance our mission of profoundly changing the trajectory of health for humanity. -

Extending Managerial Control Through Coercion and Internalisation in the Context of Workplace Bullying Amongst Nurses in Ireland

societies Article “It’s Not Us, It’s You!”: Extending Managerial Control through Coercion and Internalisation in the Context of Workplace Bullying amongst Nurses in Ireland Juliet McMahon * , Michelle O’Sullivan, Sarah MacCurtain, Caroline Murphy and Lorraine Ryan Department of Work & Employment Studies, University of Limerick, V94 T9PX Limerick, Ireland; [email protected] (M.O.); [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (L.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article investigates why workers submit to managerial bullying and, in doing so, we extend the growing research on managerial control and workplace bullying. We employ a labour process lens to explore the rationality of management both engaging in and perpetuating bullying. Labour process theory posits that employee submission to workplace bullying can be a valuable method of managerial control and this article examines this assertion. Based on the qualitative feedback in a large-scale survey of nurses in Ireland, we find that management reframed bullying complaints as deficiencies in the competency and citizenship of employees. Such reframing took place at various critical junctures such as when employees resisted extremely pressurized environments and when they resisted bullying behaviours. We find that such reframing succeeds in suppressing resistance and elicits compliance in achieving organisational objectives. We demonstrate how a pervasive bullying culture oriented towards expanding management control weakens an ethical Citation: McMahon, J.; O’Sullivan, climate conducive to collegiality and the exercise of voice, and strengthens a more instrumental M.; MacCurtain, S.; Murphy, C.; Ryan, climate. Whilst such a climate can have negative outcomes for individuals, it may achieve desired L.