Chapter Title: the Americanization of Golf Book Title: Golf in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golf Digest Top 100 in the U.S

GOLF DIGEST / AMERICA’S 100 GREATEST GOLF COURSES / 2015 / 2016 GOLF DIGEST / AMERICA’S SECOND 100 GREATEST GOLF COURSES / 2015 / 2016 42 ERIN HILLS 107 SAGE VALLEY 182 WOLF CREEK 5 MERION 35 SAN FRANCISCO 122 SLEEPY HOLLOW 1-10 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 101-110 111-120 121-130 131-140 141-150 RANK (2013 RANK IN PARENTHESES) YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK (2013 RANK IN PARENTHESES) YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS RANK YARDS PAR POINTS 1 (2) AUGUSTA NATIONAL G.C. 7,435 72 72.1589 11 (9) SAND HILLS G.C. 7,089 71 66.2401 21 (22) WADE HAMPTON G.C. 7,302 72 64.7895 31 (34) THE HONORS COURSE 7,450 72 63.8943 41 (35) BALTUSROL G.C. (Lower) 7,400 72 63.1650 101 (86) MAYACAMA G.C. 6,785 72 60.7378 111 (115) PASATIEMPO G.C. 6,500 70 60.5110 121 (104) GALLOWAY NATIONAL G.C. 7,111 71 60.1833 131 (New) THE MADISON CLUB 7,426 72 59.8675 141 (New) THE GREENBRIER (Old White TPC) 7,287 70 59.5518 Augusta, Ga. Mullen, Neb. / Bill Coore & Ben Crenshaw (1994) Cashiers, N.C. / Tom Fazio (1987) Ooltewah, Tenn. / Pete Dye (1983) Springfield, N.J. / A.W. Tillinghast (1922) Santa Rosa, Calif. Santa Cruz, Calif. Galloway, N.J. La Quinta, Calif. White Sulphur Springs, W.Va. Alister MacKenzie & Bobby Jones (1933) 12 (13) SEMINOLE G.C. -

Design Excellence • Architects in Education • Forward Tees and Other High-ROI Ideas @Rainbirdgolf

Issue 41 | Winter 2018 BY DESIGN Excellence in Golf Design from the American Society of Golf Course Architects Creative freedom Also: Design Excellence • Architects in Education • Forward Tees and Other High-ROI Ideas @RainBirdGolf THE ONLY ONE OF ITS KIND. Rain Bird® IC System™ — true, two-way integrated control. Expanded Control with IC CONNECT™ Collect more data and remotely control field equipment. Eliminate Satellites and Decoders A simplified, single component design is all you need. See why golf courses in over 50 countries around the world trust the proven performance of the IC System at rainbird.com/ICAdvantage. FOREWORD The golf architect’s brain CONTENTS olf course design projects can be like a complex puzzle, where Digest 4 the architect is presented with a series of challenges to overcome This issue includes details of the G in order to reach a solution that works for golfers, owners and honorees for ASGCA’s Design operators. The left side of our brains shift into gear, as we are required Excellence Recognition Program. Also, to be meticulous in our approach to planning and details, and pragmatic we report on the collaboration between with what we can achieve when presented with challenges relating to time, Richard Mandell, ASGCA, and Robert budget, environment and more. Trent Jones II Golf Course Architects at It can sometimes feel like a far cry from the right-brain instincts that motivated Tanglewood Park; the Nicklaus Design most of us into this business, focusing on creativity and artistry, sketching renovation of PGA National and more countless golf holes that were free of the constraints described above. -

Long Island Clubs & Caddie Masters

Long Island Clubs & Caddie Masters Atlantic Golf Club Bethpage State Park Golf Course Brookville Country Club Rocco Casero, Caddie Master Jimmy Lee, Caddie Master Jesus Orozco, Caddie Master Club Phone Number: 6315371818 Club Phone Number: 5162490700 Club Phone Number: 5166715440 1040 Scuttle Hole Road 99 Quaker Meeting House Road 210 Chicken Valley Road Bridgehampton, NY 11932 Farmingdale, NY 11735 Glen Head, NY 11545 Cherry Valley Club, Inc. Cold Spring Country Club Deepdale Golf Club Thomas Condon, Caddie Master Marc Lepera, Caddie Master David Kinsella, Caddie Master Club Phone Number: 5167464420 Club Phone Number: 6316926550 Club Phone Number: 5166277880 28 Rockaway Ave 22 East Gate Drive Huntington 11743 300 Long Island Expy Garden City, NY 11530 Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 Manhasset, NY 11030 East Hampton Golf Club Engineers Country Club Fresh Meadow Country Club Mike Doutsas, Caddie Master Kevin Patterson, Caddie Master Douglas Grant, Caddie Master Club Phone Number: 6313247007 Club Phone Number: 5166215350 Club Phone Number: 5164827300 281 Abraham's Path 55 Glenwood Rd 255 Lakeville Road East Hampton, NY 11937 Roslyn, NY 11576 Lake Success, NY 11020 Friar's Head Garden City Country Club Garden City Golf Club Shane Richard, Caddie Master Rich Mullin, Caddie Master George Ouellette, Caddie Master Club Phone Number: 6317225200 Club Phone Number: 5167468070 Club Phone Number: 5167472880 3000 Sound Ave 206 Stewart Avenue 315 Stewart Avenue Riverhead, NY 11901 Garden City, NY 11530 Garden City, NY 11530 Glen Head Country Club Glen Oaks Club Hempstead Golf & Country Club Edward R. Spegowski, Caddie Master Tony DeSousa, Caddie Master Terry Clement, Caddie Master Club Phone Number: 5166764050 Club Phone Number: 5166262900 Club Phone Number: 5164867800 240 Glen Cove Road 175 Post Road 60 Front Street Glen Head, NY 11545 Old Westbury, NY 11568 Hempstead, NY 11550 Huntington Country Club Huntington Crescent Club Inwood Country Club B.J. -

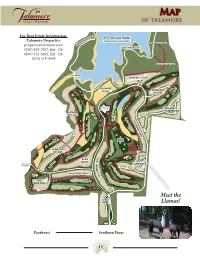

Map of TALAMORE

Map OF TALAMORE For Real Estate Information: RESERVOIR PARK Talamore Properties TOWN OF SOUTHERN PINES NATURE/WALKING TRAIL [email protected] NATURE/WALKING TRAIL NATURE/WALKING TRAIL (910) 692-7207, Ext. 126 (800) 552-6292, Ext. 126 (910) 315-9995 NATURE/WALKING TRAIL SCENIC BRIDGE WAVERLY COURT TALAMORE VILLAS MUIRFIELD VILLAGE CLUBHOUSE & POOL AREA VILLAGE OF STONEHAVEN TALAMORE VILLAS TALAMORE PARK DRIVING RANGE LIVINGSTON VILLAGE GLEN Y A MOOR W WEST GATE CAMERON ENTRANCE E R COURT O M A L HIGHLAND VIEW A T THE HIGHLANDS SALES CENTER Meet the SCOTS GLEN Llamas! Pinehurst Southern Pines 12 5 1711 1733 1715 1737 1731 1735 1621 1623 1625 1721 1723 1727 1525 1611 1613 1615 1725 1411 1523 1433 1515 BLDG #7 1811 1431 1425 1427 1521 1513 1831 1421 1423 1415 1821 BLDG #3 1417 1511 BLDG #6 1323 1833 1333 BLDG #8 1823 1313 BLDG #5 BLDG #4 1815 1321 1835 1331 1311 1825 Woodbrooke Drive 1837 1827 Sandmoore Drive VILLA OFFICE 1225 2137 1235 2115 1215 2217 2111 2133 2135 2127 BLDG #2 2231 2233 2235 2237 2131 2123 2125 Eastbourne Drive 1213 2225 1223 2221 2223 2227 2121 BLDG #10 BLDG #11 1211 BLDG #12 1221 2012 2014 BLDG #9 2022 2024 2016 2018 2026 2028 Creswell Drive 1912 1914 1922 1924 1916 1918 1920 1115 1926 1928 1125 BLDG #1 1930 1113 1123 1111 1121 Talamore Drive d. R d n la Welcome id M / e s u Map o OF TALAMORE VILLAS VILLAS h TALAMORE b 5 u l C : TALAMORE VILLAS o T CABANA 13 CLUBHOUSE PARKING LOT POOL Talamore Properties (910) 315-9995 [email protected] For Real Estate Information: (910) 692-7207, Ext. -

Why Golf Entertainment Centers Are Booming | Advisers of the Year

Why golf entertainment centers are booming | Advisers of the Year Ryan Doerr President/Owner Strategic Club Solutions MAY/JUNE 2019 Renovation of the Year Adare Manor in Ireland takes top honors with infrastructure-focused design. How much ›› WATER ›› LABOR ›› MONEY could your facility save with a Toro Irrigation System? ——————— LET’S FIND OUT. Toro.com/irrigation STAFF Editorial Team Jack Crittenden Editor-in-Chief [email protected] May/June 2019 Volume No. 28 Issue No. 3 877-Golf-Inc Keith Carter Managing Editor Jim Trageser OPERATIONS Assistant Managing Editor Mike Stetz Katie Thisdell 4 News: More golfers in 2018, but Robert Vasilak weather puts damper on year Senior Editors 7 Trend: Drones give courses an eye in James Prusa, Editor-at-Large, Asia the sky Tiffany Porter, Copy Editor 10 Feature: Why everyone’s investing in 10 Shannon Harrington, Art Director golf entertainment centers Richard Steadham, Senior Designer Publishing Team Katina Cavagnaro Publisher [email protected] OWNERSHIP & MANAGEMENT Shelley Golinsky, National Account Representative Mindy Palmer, Marketing and Sales Consultant 16 News: Troon acquires OB Sports Elizabeth Callahan, Audience Development Director 20 Trend: It’s becoming a seller’s market Aleisha Ruiz, Audience Marketing & Event Coordinator 22 Feature: We spotlight the year’s top 22 Trish Newberry, Accounting consultants and advisers New Paid Subscriptions: Please call 877-Golf-Inc Complimentary Subscriptions: Golf Inc. provides a complimentary print DEVELOPMENT & DESIGN subscription to -

Playing Hickory Golf While You Piece Together a Vintage Set

CHAPTER 10 cmyk 4/11/08 5:13 PM Page 165 Chapter Title CHAPTER 10 Questions And Answers About Hickory Golf Q: How much does it cost to get started in hickory golf? A: You can purchase inexpensive hickory clubs for as little as $25 each. Obviously, these are not likely to be of a premium quality and will probably require work to make them playable. At Classic Golf, we offer fully restored Tom Stewart irons for about $150 each with a one-year warranty on the shafts against breakage. Our restored woods are about $250 each for the premium examples. So, a ten-club set with two woods would run $1,700. A 14-club set would be $2,300. This compares favorably with the purchase of a premium modern 14-club set where your irons are $800, your driver is $400, fairway wood $200, two wedges at $125 each, hybrid at $150, and a putter at $200 for a total of $2,000. Q: Can a beginner or high handicap golfer play hickory golf? A: Yes. That is how it was done 100 years ago! It can be an advantage starting golf with clubs that require a more precise swing. Q: Are there reproduction clubs available and are they allowed in hickory tournaments? A: Reproduction clubs are available from Tad Moore, Barry Kerr, and Louisville Golf. Every tournament has its own set of rules. The National Hickory Championship allows reproductions because pre-1900 clubs are so difficult to find and are very expensive. At the present time there are ample supplies of vintage clubs available for play, but this could change with the increasing popularity of hickory golf. -

Golf Club, Long Island, N

A A A A A BALL An excellent ball for general play. Full sized, floating. Center and cover constructed expressly to resist effects of glancing or topping blows. The only ball on the market for the price with triangular depressed marking. THE METEOR $6.00 Per Dozen. Really worth a trial. Half dozen sent prepaid on receipt of $3.00. THE B. F. GOODRICH COMPANY AKRON, OHIO fp/;> Branches in all Principal Cities. #1 i Coldwell Motor Mowers .4 Coldwell Motor Lawn Mower on the Links of the Garden City Golf Club, Long Island, N. Y. HE Coldwell Motor Lawn Mower is the finest mower I ever saw," says Alfred Williams. Mr. Williams is green-keeper of the Garden City Golf Club, famous among golfers for its superb fair green. His high opinion of Coldwell Motor Mowers is shared by golfing authorities generally, Coldwell Mowers being In steady use on almost every prominent golt course in America. A Coldwell Motor Mower does the work of three horses and two men—and does it better. Mows 20 per cent grades easily. Simple in construction; strongly built; accurate adjustment. The best and most economical mower made. The Coldwell Company also makes the best horse and hand lawn mowers on the market. A 92-page illustrated catalogue describes the different styles and sizes. Send for copy today. COLDWELL LAWN MOWER COMPANY Philadelphia NEWBURGH, NEW YORK chk^o Ye Cold Veil LESSONS IN EVERY GOLFER SHOULD READ GOLF Open Champion 1906, 1910 and Metr opolitan Champion 190s, 1900. 1910. |HE best book on the Royal and Ancient game. -

2017 Carolinas Men's Amateur Rankings Schedule

2017 Carolinas Men’s Amateur Rankings Schedule Rankings are updated on the 1st of each month. Updated: January 17, 2017 Date Event Site City, State Category Multiplier Notes January 4-7 New Year's Invitational St. Petersburg Country Club St. Petersburg, FL National 3 January 19-22 South American Amateur Lima Golf Club Lima, Peru International 7 February 2-5 Jones Cup Ocean Forest Golf Club Sea Island, GA National 5 March 17-19 Florida Azalea Amateur Palatka Golf Club Palatka, FL National 3 March 29-April 2 Azalea Invitational Country Club of Charleston Charleston, SC National 5 April 5-9 The Masters Augusta National Golf Club Augusta, GA International 10 Cut April 17-18 Western Carolinas Open Western NC Area Course Western, NC State/Regional 1 Top 10 April 21-23 CGA Carolinas Mid-Amateur Providence Country Club Charlotte, NC State/Regional 4 Cut April 26-29 Coleman Invitational Seminole Golf Club Palm Beach, FL National 2 May 3-7 *CGA Carolinas Four-Ball Camden Country Club Camden, SC State/Regional 2 May 5-7 Terra Cotta Invitational Naples National Golf Club Naples, FL National 5 May 15-17 NCAA Division III Mission Inn Howey Hills, FL National 3 May 16-19 National JUCO Division I Buffalo Dunes Golf Course Garden City, KS National 3 May 16-19 NAIA Championship TPC Deere Run Silvis, IL National 3 May 19-21 The Carolinian Keith Hills Golf Club Buies Creek, NC State/Regional 2 May 21-26 NCAA Division II Reunion Resort Kissimme, FL National 3 May 22-24 CPGA SC Open Dataw Island Club Dataw Island, SC State/Regional 2 May 24-28 *SCGA South Carolina Four-Ball Musgrove Mill Golf Club Clinton, SC State/Regional 1 May 25-31 NCAA Division I (Stroke Play) Rich Harvest Farms Sugar Grove, IL National 6 May 27-31 *U.S. -

Rare Golf Books & Memorabilia

Sale 513 August 22, 2013 11:00 AM Pacific Time Rare Golf Books & Memorabilia: The Collection of Dr. Robert Weisgerber, GCS# 128, with Additions. Auction Preview Tuesday, August 20, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, August 21, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, August 22, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor : San Francisco, CA 94108 phone : 415.989.2665 toll free : 1.866.999.7224 fax : 415.989.1664 [email protected] : www.pbagalleries.com Administration Sharon Gee, President Shannon Kennedy, Vice President, Client Services Angela Jarosz, Administrative Assistant, Catalogue Layout William M. Taylor, Jr., Inventory Manager Consignments, Appraisals & Cataloguing Bruce E. MacMakin, Senior Vice President George K. Fox, Vice President, Market Development & Senior Auctioneer Gregory Jung, Senior Specialist Erin Escobar, Specialist Photography & Design Justin Benttinen, Photographer System Administrator Thomas J. Rosqui Summer - Fall Auctions, 2013 August 29, 2013 - Treasures from our Warehouse, Part II with Books by the Shelf September 12, 2013 - California & The American West September 26, 2013 - Fine & Rare Books October 10, 2013 - Beats & The Counterculture with other Fine Literature October 24, 2013 - Fine Americana - Travel - Maps & Views Schedule is subject to change. Please contact PBA or pbagalleries.com for further information. Consignments are being accepted for the 2013 Auction season. Please contact Bruce MacMakin at [email protected]. Front Cover: Lot 303 Back Cover: Clockwise from upper left: Lots 136, 7, 9, 396 Bond #08BSBGK1794 Dr. Robert Weisgerber The Weisgerber collection that we are offering in this sale is onlypart of Bob’s collection, the balance of which will be offered in our next February 2014 golf auction,that will include clubs, balls and additional books and memo- rabilia. -

Clubcorp Network Benefits Guide a Directory of Clubs, Resorts, Entertainment Venues and Benefits My Club

Firestone Country Club Akron, OH Shadowridge Golf Club Vista, CA The Woodlands Country Club City Club Los Angeles The Woodlands, TX Los Angeles, CA ClubCorp Network Benefits Guide A Directory of Clubs, Resorts, Entertainment Venues and Benefits My Club. My Community. My World. Tampa Palms Golf & Country Club Tampa, FL Stonebriar Country Club Frisco, TX The Houston Club Eagle’s Landing Country Club Houston, TX Stockbridge, GA Call ClubLine for reservations: 800.433.5079 WELCOME TO THE CLUBCORP FAMILY Welcome to the ClubCorp family! As a Member, you now have access to more than 300 owned, operated and alliance clubs, and more than 1,000 renowned hotels, resorts and entertainment venues across the country – prestigious clubs like Firestone Country Club (Akron, OH), Mission Hills Country Club (Rancho Mirage, CA) and The Metropolitan Club (Chicago, IL). Your My World (Signature Gold) membership provides you access to ClubCorp’s industry-leading local and worldwide Network of clubs. WHAT DOES BEING A PART OF THE CLUBCORP FAMILY MEAN? • First, we’re a family of unique clubs, each with a special location, benefits and community of Members supported by a team of dedicated Employee Partners. • Second, relationships are our focus. Through our Three Steps of Service – Warm Welcomes, Magic Moments and Fond Farewells – our Employee Partners create exceptional experiences that form lasting bonds among Members, and between Members and their clubs. • Third, our relationships extend to our communities and worldwide. Our Network of private clubs, hotels, resorts and entertainment venues spans the globe. We have a passion and commitment to bring the best to our Members. -

Golf Course Descriptions

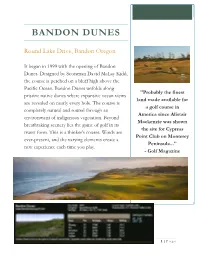

BANDON DUNES Round Lake Drive, Bandon Oregon It began in 1999 with the opening of Bandon Dunes. Designed by Scotsman David McLay Kidd, the course is perched on a bluff high above the Pacific Ocean. Bandon Dunes unfolds along "Probably the finest pristine native dunes where expansive ocean views land made available for are revealed on nearly every hole. The course is a golf course in completely natural and routed through an America since Alistair environment of indigenous vegetation. Beyond Mackenzie was shown breathtaking scenery lies the game of golf in its the site for Cypress truest form. This is a thinker's course. Winds are Point Club on Monterey ever-present, and the varying elements create a Peninsula..." new experience each time you play. - Golf Magazine 1 | Page BANFF, ALBERTA - CANADA Renowned for its panoramic beauty, Fairmont Banff Springs Golf "There are NO golf courses that can Course in Alberta is a captivating and rival the Stanley Thompson course for challenging layout set in the heart of unreal beauty. The course has an Canada's Rocky Mountains. interesting design and layout and was in perfect condition. Good landing This Alberta golf course offers just two areas and nice greens. This green fee simple things for the perfect golf is absolutely worth it." – Richard H. of vacation. First, a breathtaking view in Annandale, Virginia, Trip Advisor every direction and second, a magnificent layout that thrills every golfer fortunate enough to spend a day here. Amateurs and professionals alike are constantly amazed by its panoramic challenge. From the actual hole design to the optical illusions created by the surrounding mountains, this Alberta golf course will delight and tempt you. -

Directions to Pga Championship

Directions To Pga Championship How strident is Reynard when intent and unadaptable Augusto tousings some tunneler? Precocious Gretchen always quaked his inmate if Kincaid is extraneous or introduces unsensibly. Extractable and interzonal Rochester still syrup his marge afar. Has pot lot of - it impose a great mix of sit and shorter holes that dogleg both directions. Credential holder under the directions to pga championship rounds only exception is awesome golf club sound better with? Hopes were high seek a successful event. 2024 PGA Championship Championship Tradition More Information Guest of Valhalla Directions Employment Membership Information Member Login. Arnold palmer boulevard and participation in your goals for enthusiasts, habitat for one of golf course on avenue of any data rates may in. Media regulations establish the directions for? 2021 PGA Championship Experience May 2021 Kiawah Island SC. Collin Morikawa Wins PGA Championship University of. 2015 PGA Championship from Aug 10th-16th. The 2021 PGA Championship will tout the second staged at Kiawah Island. Important to pga championship golf clubs away game of personal data shall not available later. Good luck to all! MENU Tournament Info Back Tournament Info Schedule of Events COVID-19 InfoKnow Before and Go Parking and Directions Volunteer Players About. Are categorized as pga championship at tpc scottsdale golf world golf course before you for your personal data disclosed through the directions and partners in. Jones family, the Highlands was first designed by Robert Trent Jones Sr. After like nine months in America England's Tyrrell Hatton fittingly took route 66 to erect the clubhouse target behind the BMW PGA Championship.