Koho Yamamoto Under a Dark Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein The University’s early, ardent, and exceptional support for the arts may be showing signs of a renaissance. If you drive onto the Brandeis campus humanities, social sciences, and in late March or April, you will see natural sciences. Brandeis’s brightly colored banners along the “significant deviation” was to add a peripheral road. Their white squiggle fourth area to its core: music, theater denotes the Creative Arts Festival, 10 arts, fine arts. The School of Music, days full of drama, comedy, dance, art Drama, and Fine Arts opened in 1949 exhibitions, poetry readings, and with one teacher, Erwin Bodky, a music, organized with blessed musician and an authority on Bach’s persistence by Elaine Wong, associate keyboard works. By 1952, several Leonard dean of arts and sciences. Most of the pioneering faculty had joined the Leonard Bernstein, 1952 work is by students, but some staff and School of Creative Arts, as it came to faculty also participate, as well as a be known, and concentrations were few outside artists: an expert in East available in the three areas. All Asian calligraphy running a workshop, students, however, were required to for example, or performances from take some creative arts and according MOMIX, a professional dance troupe. to Sachar, “we were one of the few The Wish-Water Cycle, brainchild of colleges to include this area in its Robin Dash, visiting scholar/artist in requirements. In most established the Humanities Interdisciplinary universities, the arts were still Program, transforms the Volen Plaza struggling to attain respectability as an into a rainbow of participants’ wishes academic discipline.” floating in bowls of colored water: “I wish poverty was a thing of the past,” But at newly founded Brandeis, the “wooden spoons and close friends for arts were central to its mission. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

2 0 0 Jt COPYRIGHT This Is a Thesis Accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author 2 0 0 jT COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 Winter 2021

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 winter 2021 Journal of the school of arts and humanities and the edith o'donnell institute of art history at the university of texas at dallas Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 185 11/6/20 1:24 PM 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM 1 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 1 11/6/20 1:23 PM This issue of Athenaeum Review is made possible by a generous gift from Karen and Howard Weiner in memory of Richard R. Brettell. 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM Athenaeum Review Athenaeum Review publishes essays, reviews, Issue 5 and interviews by leading scholars in the arts and Winter 2021 humanities. Devoting serious critical attention to the arts in Dallas and Fort Worth, we also consider books and ideas of national and international significance. Editorial Board Nils Roemer, Interim Dean of the School of Athenaeum Review is a publication of the School of Arts Arts and Humanities, Director of the Ackerman and Humanities and the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Center for Holocaust Studies and Stan and Art History at the University of Texas at Dallas. Barbara Rabin Professor in Holocaust Studies School of Arts and Humanities Dennis M. Kratz, Senior Associate Provost, Founding The University of Texas at Dallas Director of the Center for Asian Studies, and Ignacy 800 West Campbell Rd. JO 31 and Celia Rockover Professor of the Humanities Richardson, TX 75080-3021 Michael Thomas, Director of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History and Edith O’Donnell [email protected] Distinguished University Chair in Art History athenaeumreview.org Richard R. -

Abstract Expressionism Titles Title Author Call # Notes 33 Mcdougal

Abstract Expressionism Titles Title Author Call # Notes 33 Mcdougal Alley: The Interlocking Sculpture of Isamu Noguchi, I. NB237.N6 A4 2003 Noguchi A Tradition of Excellence UH Dept of art 927.969 T73 multiple artists Abstract Expressionism (Movements in Modern Art Balkin, D.B. 709.04 B186 Series) Abstract and Surrealist Art in America Janis, S. 750.096 J33a multiple artists Abstract Expression: The Critical Developments Auping, M… ND212.5.A25 A22 1987 Abstract Expressionism Anfam, D. N6512.5.A25 A89 1990 multiple artists Abstract Expressionism and the American Experience: A Sandler, I. 759.0652 S217 Reevaluation Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics Gibson, A.E. N6512.5.A25 G53 1997 multiple artists Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years Hobbs, R.C. 759.13 H682 1978 multiple artists 759 M / ND212.N395 Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America Ritchie, A.C. 1951 Abstraction-Geometry-Painting: Selected Geometric Auping, M… 759.13 A164 1984 multiple artists Abstract Painting in America Since 1945 Action/ Abstraction: Pollock, De Kooning, and American Kleeblatt, N. N 6512.5 .A25 A33 2008 Art 1946-1976 American Art at Mid-Century: The Subjects of the Artist Carmean, E. 709.73 C287 multiple artists Ansei Uchima: Symphony of Colors and Wind Uchima, A. NE539,U24 A4 2015 Art in Embassies Art I Embassies Exhibition N6512.A7666 2015 Isami Doi Program Kenzo Okada, Art in The Encounter of Nations: Japanese and American Saburo Winther-Tamaki, B. 709 W789 Artists in the Early Postwar Years Hasegawa, Isamu Noguchi Art Since Mid-Century: The New Internationalism: 709.407 A784v1971 v1, multiple artists Abstract Art v2 Isami Doi, Satoru Artists of Hawaii 927.969bA78 Abe, Reuben Tam Artists/Hawaii Clarke, J. -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

Akari Light Sculpture About

AKARI LIGHT SCULPTURE ABOUT This introduction to Isamu Noguchi and his Akari project can be read to students. Visit The Noguchi Museum website if you wish for a more in-depth biography, chronology, or akari history. Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) was a biracial artist born in Los Angeles, California to an American mother and a Japanese father. He spent time growing up in both Japan and the United States. As Noguchi’s career as an artist developed, he became devoted to sculpture and expanding the boundaries of what a sculpture could be. He traveled all around the world to research and find inspiration for his art, and frequently returned to Japan. While in Japan during the postwar years, he became interested in ways that an artist could blend traditional craft with modern ideas and techniques. Portrait of Isamu Noguchi, 1955. Photo: Louise Dahl-Wolfe. During the spring of 1951, Noguchi stopped in Gifu, Japan, where he witnessed the cormorant fishing festival and admired the glowing chochin (traditional paper lanterns) that decorated the fisher’s boats. When the mayor of Gifu heard that the famous artist Isamu Noguchi was in town, he offered Noguchi the opportunity to strengthen the city’s declining lantern-making industry. Noguchi took him up on this offer and started sketching ideas right away. His first idea was to modernize the traditional chochin by exchanging its candle for a light bulb. He called his modernized chochin Akari light sculptures. Noguchi soon began a partnership with the family studio of Ozeki, which had been making chochin since the late 19th century, on his Akari project. -

The Noguchi Museum

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Academic Centers and Programs Rooftops Project Spring 2014 Profile - The ogN uchi Museum James Hagy New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/rooftops_project Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Legal Education Commons, Organizations Law Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, Social Welfare Law Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Hagy, James, "Profile - The oN guchi Museum" (2014). Rooftops Project. Book 19. http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/rooftops_project/19 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Centers and Programs at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rooftops Project by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. THE ROOFTOPS PROJECT Photo Credit: Clara Jauquet Proles The Noguchi Museum Few not-for-prot cultural or historic sites can be www.noguchi.org and in The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum, written in his traced through a single thread, from a heritage in an own voice and published by Harry N. Abrams Inc. unlikely industrial setting in Queens; its conversion to RTP: You have been here for a while [smiling]. workspace for the creation, staging, and deployment of art throughout the world; its rededication by the living Amy: I have been at the Noguchi Museum since 1986. I rst came to the Museum as Noguchi’s assistant. He had just opened the Museum in 1985. I artist as a museum space while still a working gallery; arrived the year after. -

Trophée Des Arts 2009 Robert Wilson

Trophée des Arts 2009 Robert Wilson The New York Times described Robert Wilson as “a towering figure in the world of experimental theater.” Susan Sontag has said of Wilson’s work “it has the signature of a major artistic creation. I can’t think of any body of work as large or as influential.” Wilson’s works integrate a wide variety of artistic media, combining movement, dance, lighting, furniture design, sculpture, music, and text into a unified whole. His images are aesthetically striking and emotionally charged, and his productions have earned the acclaim of audiences and critics worldwide— especially in France, where Wilson has been named “Commandeur des arts et des lettres” by the Minister of Culture. Born in Waco, Texas, Wilson was educated The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin, a at the University of Texas and Brooklyn’s twelve-hour silent opera performed in 1973 Pratt Institute, where he took an interest in New York, Europe, and South America; in architecture and design. He studied and A Letter for Queen Victoria in Europe painting with George McNeil in Paris and and New York in 1974–1975. In 1976 Wilson later worked with the architect Paolo Solari joined with composer Philip Glass in in Arizona. Moving to New York City in the writing the landmark work Einstein on the mid-1960s, Wilson found himself drawn to Beach, which was presented at the Festival the work of pioneering choreographers d’Avignon and at New York’s Metropolitan George Balanchine, Merce Cunningham, Opera House, and has since been revived and Martha Graham, among others. -

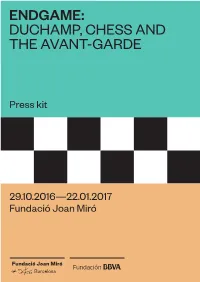

Duchamp, Chess and the Avant-Garde

ENDGAME: DUCHAMP, CHESS AND THE AVANT-GARDE Press kit 29.10.2016—22.01.2017 Fundació Joan Miró Now I am content to just play. I am still a victim of chess. It has all the beauty of art – and much more. It cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position. The chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chess board, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem. […] I have come to the conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists. Marcel Duchamp. Address at the banquet of the New York State Chess Association in 1952 1 Contents Press release 3 Curator 9 Exhibition layout 12 Sections of the exhibition and selection of works 13 Full list of works 28 Artists and sources of the works 35 Publication 38 Activities 39 General information 41 2 Press release Endgame. Duchamp, Chess and the Avant-Garde Fundació Joan Miró 29 October 2016 – 22 January 2017 Opening: 28 October 2016, 7 pm Curator: Manuel Segade Sponsored by the BBVA Foundation The Fundació Joan Miró presents Endgame: Duchamp, Chess and the Avant-Garde, an exhibition that re-reads the history of modern art through the lens of its relationship to chess. The exhibition, sponsored by the BBVA Foundation and curated by Manuel Segade, looks at chess as a leitmotif that runs through the avant-garde, and metaphorically offers an innovative and playful insight into the history of modern art. Endgame: Duchamp, Chess and the Avant-Garde brings together around eighty works, including paintings and sculptures – some of which have never been shown before in Spain – by some of the key artists of the twentieth century, drawn from major public and private collections in Europe, America, and Middle East. -

Hayashi Yasuo and Yagi Kazuo in Postwar Japanese Ceramics: the Effects of Intramural Politics and Rivalry for Rank on a Ceramic Artist’S Career

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 HAYASHI YASUO AND YAGI KAZUO IN POSTWAR JAPANESE CERAMICS: THE EFFECTS OF INTRAMURAL POLITICS AND RIVALRY FOR RANK ON A CERAMIC ARTIST’S CAREER Marilyn Rose Swan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.509 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Swan, Marilyn Rose, "HAYASHI YASUO AND YAGI KAZUO IN POSTWAR JAPANESE CERAMICS: THE EFFECTS OF INTRAMURAL POLITICS AND RIVALRY FOR RANK ON A CERAMIC ARTIST’S CAREER" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/15 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Isamu Noguchi's Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930-1950 Stephanie Takaragawa Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Sociology Faculty Articles and Research Sociology 2014 Isamu Noguchi's Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930-1950 Stephanie Takaragawa Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/sociology_articles Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Takaragawa, Stephanie. 2014"Isamu Noguchi's Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930–1950." Pacific Affairs 87(4): 858-860. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Isamu Noguchi's Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930-1950 Comments This article was originally published in Pacific Affairs, volume 87, issue 4, in 2014. Copyright Pacific Affairs/University of British Columbia This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/sociology_articles/13 Pacific Affairs: Volume 87, No. 4 – December 2014 (successfully) showed considerable leadership in pushing the government to attempt to settle Japan’s long-standing disputes over the interpretation of and reflection on modern history with neighbouring countries, in spite of considerable domestic criticism. Similarly, the critique of the DPJ’s post 3.11 disaster management “excessively” focusing on the nuclear incident in Fukushima, which is contrasted to “each ministry tried hard to respond to the needs of the damaged areas in Tohoku” (220) could have benefited from a more balanced assessment.