Tall Poppy Syndrome & Patriarchal Femininity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action. Power. Freedom. FY 2018 Annual Report Action

Action. Power. Freedom. FY 2018 Annual Report Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Freedom. Action. Power. Freedom. Action. Power. This is our moment— “and I truly believe in us. Because we–NARAL, our members, our extended community–have all of the ingredients necessary to win this fight. This is the fight that NARAL, and all of you, were made for.” —Ilyse G. Hogue, President 2 FY 2018 Annual Report Contents A Message From Our President .............................................................................. 5 Action. Power. Freedom. .................................................................................................6 Financial Overview ...........................................................................................................14 A Message From Our Board Chairs...................................................................19 Boards of Directors & Executive Staff .........................................................20 -

February 26, 2020 Chairman David Skaggs Co-Chairwoman Allison

February 26, 2020 Chairman David Skaggs Co-Chairwoman Allison Hayward Office of Congressional Ethics 425 3rd Street, SW Suite 1110 Washington, DC 20024 Dear Chairman Skaggs and Co-Chairwoman Hayward: We write to request that the Office of Congressional Ethics (“OCE”) investigate whether Representative Devin Nunes is receiving free legal services in violation of the Rules of the House of Representatives (“House rules”). Specifically, Representative Nunes retained an attorney who represents him in several defamation lawsuits in various courts where he seeks a total of nearly $1 billion in damages. House rules prohibit a Member from receiving free legal services, unless the Member establishes a Legal Expense Fund (“LEF”). According to the House Legislative Resource Center, Representative Nunes has not filed any of the required reports to establish an LEF. The relevant facts detailed below establish that the OCE Board should authorize an investigation of Representative Nunes. Representative Nunes’s overt involvement with the highly-publicized lawsuits threatens to establish a precedent that the Legal Expense Fund (“LEF”) regulations no longer apply to Members. Although Representative Nunes is entitled to legal representation and he may pursue any legal action to protect and defend his interests, he must comply with House rules. An OCE investigation will preserve Representative Nunes’s legal right to counsel while upholding well-established House rules and precedent. House Rules Prohibit Members from Receiving Discounted or Free Legal Services A Member of the House of Representatives “may not knowingly accept a gift” with limited exceptions.1 A “gift” is defined to include “a gratuity, favor, discount, entertainment, hospitality, loan, forbearance, or other item having monetary value. -

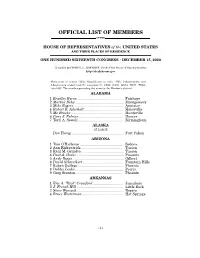

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

The Importance of Politics to CAALA and the Importance of CAALA to Politicians THIS ELECTION IS ABOUT YOUR PRACTICE

CAALA President Mike Arias ARIAS SANGUINETTI WANG & TORRIJOS, LLP October 2018 Issue The importance of politics to CAALA and the importance of CAALA to politicians THIS ELECTION IS ABOUT YOUR PRACTICE In a few short weeks, the mid-term Republicans, we will take back the House. efforts to pare down, strip down and take elections will take place, and I hope I don’t What does this mean to you as a Trial away access to justice.” Swalwell added that have to tell you how important this election Lawyer? It means that the wrath of legislta- “23 seats are between where we are and cut- is for consumer attorneys and the people tion that has emanated out of the ting in half our time in hell. We can prove we represent. Like so many CAALA mem- Republican-controlled House – that is that we are better than that in America.” bers, politics means a lot to me; not just designed to limit consumer rights, deny Katie Hill and Gil Cisneros both said they because I’m CAALA’s President and I’m trial by jury and eliminate our practices – have lived a life of service. Katie as a nurse and about to be installed as President of our will stop. Cisneros in the Navy. They say they are both state trial lawyer association, CAOC. And As is usually the case, California is at the fighting to keep President Trump from taking not because I’m a political junkie who center of the national political landscape, away what trial lawyers work to do. -

Eleni Kounalakis (Lt. Governor) Josh Harder (U.S

California Gavin Newsom (Governor) Eleni Kounalakis (Lt. Governor) Josh Harder (U.S. House, CA-10) TJ Cox (U.S. House, CA-21) Katie Hill (U.S. House, CA-25) Katie Porter (U.S. House, CA-45) Harley Rouda (U.S. House, CA-48) Mike Levin (U.S. House, CA-49) Ammar Campa-Najjar (U.S. House, CA-50) Buffy Wicks (State Assembly, District 15) Colorado Jared Polis (Governor) Dianne Primavera (Lt. Governor) Phil Weiser (Attorney General) Jena Griswold (Secretary of State) Tammy Story (State Senate, District 16) Jessie Danielson (State Senate, District 20) Brittany Pettersen (State Senate, District 22) Faith Winter (State Senate, District 24) Dylan Roberts (State House, District 26) Dafna Michaelson Jenet (State House, District 30) Shannon Bird (State House, District 35) Rochelle Galindo (State House, District 50) Julie McCluskie (State House, District 61) Georgia Stacey Abrams (Governor) Sarah Riggs Amico (Lt. Governor) Matthew Wilson (State House, District 80) Shelly Hutchinson (State House, District 107) Illinois J.B. Pritzker (Governor) Juliana Stratton (Lt. Governor) Kwame Raoul (Attorney General) Sean Casten (U.S. House, IL-6) Brendan Kelly (U.S. House, IL-12) Lauren Underwood (U.S. House, IL-14) Iowa Deidre DeJear (Secretary of State) Tim Gannon (Secretary of Agriculture) Kristin Sunde (State House, District 42) Jennifer Konfrst (State House, District 43) Eric Gjerde (State House, District 67) Laura Liegois (State House, District 91) Maine Louis Luchini (State Senate, District 7) Laura Fortman (State Senate, District 13) Linda Sanborn (State Senate, District 30) Nevada Jacky Rosen (U.S. Senate) Susie Lee (U.S. House, NV-3) Steven Horsford (U.S. -

Head High a 6 X 1 Hour Drama Series For

HEAD HIGH A 6 X 1 HOUR DRAMA SERIES FOR For more information contact Rachael Keereweer Head of Communications, South Pacific Pictures DDI: +64 9 839 0347 SOUTH PACIFIC Email: [email protected] PICTURES www.southpacificpictures.com Facebook @HeadHighWhanau Instagram @HeadHighWhanau Twitter @HeadHighWhanau SYNOPSIS Set in the home of a struggling but hopeful working-class family, six drama-packed episodes chart the rise of high school rugby stars, Mana and Tai. Two brothers, one dream. Under the guidance of their step-father coach Vince and police officer mum Renee, the boys fight to achieve the ‘Kiwi’ dream of the black jersey. But will the game of rugby bring this whanau together or tear them apart forever? Mana and Tai Roberts are star players of Southdown High School’s First XV, which under the guidance of their step-father and coach Vince O’Kane, has just made it into Auckland’s premiere tournament, the 1A. Stakes are high – the struggling, low-decile school desperately needs a win. But the team takes a blow when Christian Deering – Southdown High First XV captain and Mana’s best friend – is poached by their bitter rivals, wealthy neighbouring private school Saint Isaac’s College. This sets in motion an all-out war between the two schools. As the bad blood spills over, Mana and Tai’s mum Renee has to deal with the brawls – she’s the local cop and she’s starting to get sick of rugby and the trouble it brings. She’s already trying to raise her sons, and her daughter Aria, who lives in the shadow of her rugby-playing brothers. -

Jason Whyte. Height 177 Cm

Actor Biography Jason Whyte. Height 177 cm Awards. 2014 Male Performance of the Year Award for "The Caretaker" 2014 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Nominee –Outstanding Performance for"Peninsula" 2011 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Nominee –Best Supporting Actor/Outstanding Performance for"August Osage County/When the rain 2009 Hackman Auckland Theatre Awards –Best Accent for"Flintlock Musket/Apollo 13" 2008 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Nominee - Best Performance-Apollo 13: Mission Control 2005 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Winner-Outstanding Performance-The Tutor 2005 New Zealand Screen Awards Winner-Best Performance by a Supporting Actor-The Insiders Guide to Happiness 2004 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Nomination-Production of the Year-Shape of Things 2003 New Zealand Film Awards Nomination-Best Actor-Kombi Nation 2003 New Zealand Film Awards Nomination-Best Screenplay-Kombi Nation 1998 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Nomination-Best Supporting Actor-Mojo 1998 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Winner-Most Original Theatre-Dirt 1997 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards Nomination-Best Supporting Actor-Bent Feature Film. 2017 Mortal Engines Food Hawker Hungry City LTD Dir. Peter Jackson 2009 Until Proven Innocent Nicholas Reekie Dir. Peter Burger (Support) 2008 Second Hand Wedding Steve Dir. Paul Murphy (Support) 2008 Home By Christmas Bill Preston Doublehead Films Ltd (Support) Dir. Gaylene Preston Prd. Sue Rogers 2008 Avatar Cryo Mad Tech 880 Productions (Support) Dir. James Cameron PO Box 78340, Grey Lynn, www.johnsonlaird.com Tel +64 9 376 0882 Auckland 1245, NewZealand. www.johnsonlaird.co.nz Fax +64 9 378 0881 Jason Whyte. Page 2 Feature continued... 2005 Eagle vs Shark Michael Sad Animals (Support) Dir. Taika Cohen 2004 King Kong Venture Crew Big Primate Pictures (Support) Dir. -

The Topp Twins: Untouchable Girls

PRESENTS THE TOPP TWINS: UNTOUCHABLE GIRLS A film directed by Leanne Pooley PRESS KIT April 2010 Runtime: 84 minutes USA PUBLICITY CONTACT: Jim Dobson, INDIE PR | e: [email protected] | p: (818) 753 0700 | c: (323) 896 6006 PRODUCTION COMPANY CONTACT: Arani Cuthbert, Producer | e: [email protected] | p: +64 9 360 9852 CONTENTS Synopsis 3 Awards 5 Screenings 6 What the Press Say 7 Director‟s Statement 11 Producer‟s Statement 13 About the Filmmakers 14 The Topp Twins‟ Biography 17 Quotes from the Movie 19 The Topp Twins‟ Characters 21 Camp Mother‟s delicious recipe for hot scones 22 How to make Ken Moller‟s fly 23 - The „Camp Mother Wuzzywing, Moist Fly‟ Credits 24 Select Press Reviews 30 (Movie and Topp Twins general) 2 SYNOPSIS Winner of the Cadillac People‟s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival 2009 „The Topp Twins: Untouchable Girls‟ tells the story of the world‟s only comedic, singing, yodelling lesbian twin sisters, Lynda and Jools Topp, whose political activism and unique brand of entertainment has helped change New Zealand‟s social landscape. In the process they have become well-loved cultural icons. This is the first time that the irrepressible Kiwi entertainment double act, Jools and Lynda Topp's extraordinary personal story has been told. As well as rarely seen archive footage and home movies, the film features a series of special interviews with some of the Topp's infamous comedy alter-egos including candid chats with the two Kens, Camp Mother and Camp Leader, the Bowling Ladies and the Posh Socialite sisters, Prue and Dilly. -

To Download The

Las Cruces Transportation July 9 - 15, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Cecily Strong and Keegan-Michael Key star in “Schmigadoon!,” premiering Friday on Apple TV+. Call us to make a reservation today! We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more It’s singing! It’s dancing! Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. It’s ‘Schmigadoon!’ Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section July 9 - 15, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “The Mighty Ones” “Movie: Exit Plan” “McCartney 3,2,1” “This Way Up” This co-production of Germany, Denmark and Paul McCartney is among the executive A flood, a home makeover and a new feathery The second season of this British comedy from Norway stars Nicolaj Coster-Waldau (“Game of producers of this six-episode documentary friend are ahead for offbeat pals Rocksy, Twig, writer, creator and star Aisling Bea finds her Thrones”) as Max, an insurance adjuster in the series that features intimate and revealing Leaf and Very Berry in their unkempt backyard character of Aine getting back up to speed midst of an existential crisis, who checks into a examinations of musical history from two living domain as this animated comedy returns for following her nervous breakdown, leaving rehab secret hotel that specializes in elaborate assisted legends — McCartney and acclaimed producer its second season. -

Entertained at Home – New Online Ideas from Comedians to Help with the Lockdown Boredom and the Best on Demand Stand-Up and Tv Comedy

ENTERTAINED AT HOME – NEW ONLINE IDEAS FROM COMEDIANS TO HELP WITH THE LOCKDOWN BOREDOM AND THE BEST ON DEMAND STAND-UP AND TV COMEDY From setting online tasks to locked down families, to new podcasts to raise the spirits, or reliving the fun of a trip to the theatre for a stand-up show and discovering an acclaimed box set. Below is a guide to what’s there and how to find them. This will be updated intermittently on our press centre here. ONLINE Alex Horne – Home Tasking (Twitter @AlexHorne) “Taskmaster is one of the most consistently funny comedy game shows on television” ★★★★ Sarah Hughes, The I Alex Horne (creator and star of Emmy and Bafta nominated Taskmaster) will be setting tasks from home to keep families entertained and as a nice diversion from everything that’s happening in the news. Using the hashtag #HomeTasking, Alex will set a brand new task at 9am on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday starting this week to coincide with kids being at home from the school closures. Greg Davies will be reprising his role at The Taskmaster and will be scoring people’s entries with points awarded and a winner announced each week. You can watch Alex explain Home Tasking here Iain Stirling – Gaming (Twitch @iainstirling) “At his best the Edinburgh native is an unhinged free-form anecdotist” ★★★★ Mark Wareham, The Mail On Sunday BAFTA-winning comedian Iain Stirling (Love Island, Taskmaster) is welcoming the public to join him playing on the world’s leading streaming service for gamers, Twitch from Monday to Wednesday at 7pm. -

Pathways to the International Market for Indigenous Screen Content: Success Stories, Lessons Learned from Selected Jurisdictions and a Strategy for Growth

PATHWAYS TO THE INTERNATIONAL MARKET FOR INDIGENOUS SCREEN CONTENT: SUCCEss STORIES, LEssONS LEARNED FROM SELECTED JURISDICTIONS AND A STRATEGY FOR GROWTH Jan. 31st, 2019 PREPARED FOR SUBMITTED BY imagineNATIVE Maria De Rosa 401 Richmond St. West, Suite 446 Marilyn Burgess Toronto, Ontario M5V 3A8 www.communicationsmdr.com CONTENTS Pathways to the International Market for Indigenous Screen Content: Success Stories, Lessons Learned From Selected Jurisdic-tions and a Strategy For Growth ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS P. 6 FOREWORD P. 8 INTRODUCTION P. 10 I. THE NEW CONTEXT: A RISING TIDE OF INDIGENOUS PRODUCTION P. 12 II. SUCCESS STORIES: CASE STUDIES OF CANADIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FILMS, TELEVISION PROGRAMS AND DIGITAL MEDIA P. 22 III. LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUCCESS OF INTERNATIONAL INDIGENOUS SCREEN CONTENT P. 42 IV. PATHWAYS TO THE INTERNATIONAL MARKET FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE INDIGENOUS SCREEN SECTOR IN CANADA P. 56 ANNEX 1: SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY P. 72 ANNEX 2: SUMMARY OF RESULTS OF ON-LINE QUESTIONNAIRE WITH FESTIVALS P. 78 ANNEX 3: LIST OF INTERVIEWEES P. 90 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Pathways to the International Market for Indigenous Screen Content: Success Stories, Lessons Learned From Selected Jurisdic-tions and a Strategy For Growth WE WISH TO THANK ADRIANA CHARTRAND, INSTITUTE COORDINATOR FOR IMAGINENATIVE FOR HER CONTRIBUTION TO THIS REPORT. AS AN INTERN ON THE CONSULTING TEAM, ADRIANA’S PROFESSIONALISM, DEEP KNOWLEDGE OF THE INDIGENOUS SCREEN-BASED SECTOR AND HER DEDICATION WERE INSTRUMENTAL TO THE SUCCESS OF THIS REPORT. SHE CONTRIBUTED TO THE RESEARCH AND WRITING OF THE CASE STUDY ANALYSIS OF THE SUCCESS STORIES FEA-TURED IN THIS REPORT, PROFILES OF CANADIAN CREATORS, THE ANALYSIS OF THE ON-LINE SURVEY, AS WELL AS GENERAL OTHER RESEARCH. -

New Online Ideas from Comedians to Help with the Lockdown Boredom and the Best on Demand Stand-Up and Tv Comedy

ENTERTAINED AT HOME – NEW ONLINE IDEAS FROM COMEDIANS TO HELP WITH THE LOCKDOWN BOREDOM AND THE BEST ON DEMAND STAND-UP AND TV COMEDY From setting online tasks to locked down families, to new podcasts to raise the spirits, or reliving the fun of a trip to the theatre for a stand-up show and discovering an acclaimed box set. Below is a guide to what’s there and how to find them. This will be updated intermittently on our press centre here. ONLINE Alex Horne – Home Tasking (Twitter @AlexHorne) “Taskmaster is one of the most consistently funny comedy game shows on television” ★★★★ Sarah Hughes, The I Alex Horne (creator and star of Emmy and Bafta nominated Taskmaster) will be setting tasks from home to keep families entertained and as a nice diversion from everything that’s happening in the news. Using the hashtag #HomeTasking, Alex will set a brand new task at 9am on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday starting this week to coincide with kids being at home from the school closures. Greg Davies will be reprising his role at The Taskmaster and will be scoring people’s entries with points awarded and a winner announced each week. You can watch Alex explain Home Tasking here Harry Baker – Something Borrowed (@ainstirling) “[Harry Baker’s] intricate, quick-fire rhymes have always been on the impressive side of mind-blowing" The Scotsman Something Borrowed is the brainchild of World Poetry Slam Champion Harry Baker where he and a different guest from the worlds of comedy, music, and performance poetry share something old, new, borrowed and blue from their respective art forms.