An Analysis of State Underage Drinking Policies and Adolescent Alcohol Use Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drinking and Driving and Underage

Southern Pines Police Department Safety Tips Drinking & Driving Underage Consumption Help prevent driving under the influence of alcohol. The life you save may be someone you care about, might be your neighbor, or maybe even YOU! We need to remember the simple fact that alcohol is a drug. Alcohol is a depressant and greatly affects ones' ability to operate a motor vehicle or machinery safely. The formula for intoxication is rather easy to comprehend. A person who weighs about 150 pounds and then consumes a 12 ounce bottle of domestic beer, a 6 ounce glass of wine, or a 1 ounce shot of 90 proof whiskey will have a blood alcohol content (BAC) of about .02% if tested within one hour. Remember the limit for Driving While Impaired (DWI) is .08% BAC (.04% if driving a Commercial Motor Vehicle), which is usually 3 standard drinks within an hour. This places the person’s blood alcohol content over the DWI limit. Someone with a BAC limit of .05% is 50% more likely to be involved in a car crash. The potential for crashes increas as the level of intoxication increases. Don't let this happen to you or someone you know. Help keep our roads safe, know “when to say when”, and drive sober. Use a designated driver and be a friend – don’t let others drive if they have been drinking. Be aware of impairment through drugs or medication. Even prescription medication can affect the ability to drive and be safe. Follow all warning labels on medications and do not drive until you are aware of how you will react to the medication. -

Efficacy of the Ria Treatment Platform: the First 230 Patients

Efficacy of the Ria Treatment Platform The First 230 Patients John Mendelson MD1,2, Mary Mitchell PhD2, Jan Gryczynski PhD2, Steven Carswell PhD2, Robert Schwartz MD2 Ria Health1, San Francisco, CA and Friends Research Institute2, Baltimore MD Abstract How it works Clinician Facing Screenshot Legend Aim: To investigate longitudinal trends in blood alcohol content (BAC) assessments during a novel telehealth treatment for alcohol use disorder. Each visualization shows the progress of Ria Health patients in the treatment program Background: Despite available, efficacious treatments for alcohol use disorder Legend All data is based on objective measurement of BAC collected using the integrated bluetooth (AUD), only 6.7% of the 15.1 million people diagnosed with AUD in 2015 sought breathalyzer. treatment. Barriers such as stigma and lack of transportation make telemedicine X-axis is “Day in Treatment”: negative days are the baseline period (pre medication) starting by smartphone an attractive alternative. The Ria Health platform is a telemedicine at day -7 and progressing to day -1, positive days start with the first day on craving- program and smartphone app to help people with AUD decrease their alcohol reduction medications which is when the full set of Ria Health treatment interventions are consumption. Patients access a physician, obtain medication to curb alcohol underway: technology supported at-home medical management, coaching to assist in cravings, and receive support from a recovery coach. As part of the behavior modification, objective measurement and feedback, and social support. program patients track their BAC through daily breathalyzer assessments linked to their smartphones. Y-axis is a 28-day moving average of the metric. -

Alcohol Withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal TERMINOLOGY CLINICAL CLARIFICATION • Alcohol withdrawal may occur after cessation or reduction of heavy and prolonged alcohol use; manifestations are characterized by autonomic hyperactivity and central nervous system excitation 1, 2 • Severe symptom manifestations (eg, seizures, delirium tremens) may develop in up to 5% of patients 3 CLASSIFICATION • Based on severity ○ Minor alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4, 5 – Manifestations occur early, within the first 48 hours after last drink or decrease in consumption 6 □ Manifestations develop about 6 hours after last drink or decrease in consumption and usually peak about 24 to 36 hours; resolution occurs in 2 to 7 days 7 if withdrawal does not progress to major alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4 – Characterized by mild autonomic hyperactivity (eg, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, hyperreflexia), mild tremor, anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbances (eg, insomnia, vivid dreams), gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, anorexia, nausea, vomiting), headache, and craving alcohol 4 ○ Major alcohol withdrawal syndrome 5, 4 – Progression and worsening of withdrawal manifestations, usually after about 24 hours from the onset of initial manifestations 4 □ Manifestations often peak around 50 hours before gradual resolution or may continue to progress to severe (complicated) withdrawal, particularly without treatment 4 – Characterized by moderate to severe autonomic hyperactivity (eg, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, hyperreflexia, fever); marked tremor; pronounced anxiety, insomnia, -

The Effects of 0.08 Bac Laws

THE EFFECTS OF 0.08 BAC LAWS Robert Apsler, Ph.D. A.R. Char, M.S., MBA Wayne M. Harding, Ed.M., Ph.D. Rainbow Technology Inc. and Terry M. Klein National Highway Traffic Safety Administration April 1999 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Straightforward and powerful reasons exist for lowering the legal limit of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) from 0.10 to 0.08. In 1964, Borkenstein et al. showed that drivers who had been drinking were more likely to be involved in a crash than sober drivers, and that beginning with low BACs, the greater the level of intoxication, the higher the probability of being in a crash. Other investigators have replicated and refined Borkenstein et al.'s original findings. More recently, Mounce and Pendleton (1992) extended this line of research by showing that driver BAC is associated with the probability of being responsible for a crash in which they were involved. Research also shows that virtually all drivers, even experienced drivers, are significantly impaired with regard to critical driving tasks at 0.08 BAC. The strong relationship between BAC level, probability of crash involvement, and increased impairment, has led a growing number of states to lower their legal BAC limits. To date, 16 states and the District of Columbia have lowered the BAC limit to 0.08 for adult drivers. It is hypothesized that implementing a 0.08 BAC law has a synergistic effect on the other components of the anti-drunk driving system, namely the enforcement, adjudication, judicial, licensing, and public information and education components. The U.S. experience suggests that combating drunk driving is most effective when ALL of the components are at play. -

Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) Chart for Oklahoma

Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) Chart for Oklahoma Here are two sex-weighted charts for an alternate method of calculating an approximate BAC level... OKLAHOMA ALCOHOL IMPAIRMENT CHART FOR MEN APPROXIMATE BLOOD ALCOHOL PERCENTAGE DRINKS* BODY WEIGHT IN POUNDS EFFECT ON PERSON 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 0 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 ONLY SAFE DRIVING LIMIT 1 .04 .03 .03 .02 .02 .02 .02 .02 IMPAIRMENT BEGINS. 2 .08 .06 .05 .05 .04 .04 .03 .03 3 .11 .09 .08 .07 .06 .06 .05 .05 DRIVING SKILLS 4 .15 .12 .11 .09 .08 .08 .07 .06 SIGNIFICANTLY AFFECTED. 5 .19 .16 .13 .12 .11 .09 .09 .08 ** CRIMINAL PENALTIES IN OKLAHOMA AT .06% 6 .23 .19 .16 .14 .13 .11 .10 .09 7 .26 .22 .19 .16 .15 .13 .12 .11 8 .30 .25 .21 .19 .17 .15 .14 .13 LEGALLY INTOXICATED. 9 CRIMINAL PENALTIES IN ALL .34 .28 .24 .21 .19 .17 .15 .14 STATES 10 .38 .31 .27 .23 .21 .19 .17 .16 Subtract .01% for each 40 minutes of drinking. * One drink is equal to 1¼ oz. of 80-proof liquor, 12 oz. of beer, or 4 oz. of table wine. **ALL states have a .08 BAC per se law OKLAHOMA ALCOHOL IMPAIRMENT CHART FOR WOMEN APPROXIMATE BLOOD ALCOHOL PERCENTAGE DRINKS* BODY WEIGHT IN POUNDS EFFECT ON PERSON 90 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 ONLY SAFE DRIVING 0 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 LIMIT 1 .05 .05 .04 .03 .03 .03 .02 .02 .02 IMPAIRMENT BEGINS. -

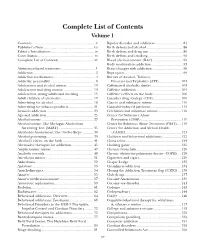

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents .....................................................................v Bipolar disorder and addiction .............................. 84 Publisher’s Note .......................................................vii Birth defects and alcohol ....................................... 86 Editor’s Introduction ............................................... ix Birth defects and drug use ..................................... 89 Contributors ............................................................. xi Birth defects and smoking ...................................... 90 Complete List of Contents ......................................xv Blood alcohol content (BAC) ................................ 92 Body modification addiction .................................. 93 Abstinence-based treatment ..................................... 1 Brain changes with addiction ................................. 96 Addiction ................................................................... 2 Bupropion ............................................................... 99 Addiction medications .............................................. 4 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Addictive personality ................................................ 8 Firearms and Explosives (ATF) ....................... 101 Adolescents and alcohol misuse............................. 10 Caffeinated alcoholic drinks ................................ 103 Adolescents and drug misuse ................................. 13 Caffeine addiction ............................................... -

Alcohol Use, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

33.3_9.1.10.qxd:32(1).qxp 9/8/10 11:43 AM Page 229 SPECIAL SECTION: MODELING HIV AND ALCOHOL’S EFFECTS FOCUS ON THE LIVER: ALCOHOL USE, HIGHLY The increasing problem of liver disease in the HIV pop ACTIVE ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY, AND LIVER ulation can be attributed to a variety of factors, including coinfection with HCV or hepatitis B virus (HBV), alcohol DISEASE IN HIVINFECTED PATIENTS abuse, and toxic effects of the HAART medications on the liver (i.e., HAART hepatotoxicity). For example, depending Shirish Barve, Ph.D.; Rama Kapoor, M.D.; Akshata on the specific combination of medications used, up to Moghe, M.B.B.S; Julio A. Ramirez, M.D.; John W. 30 percent of patients experience severe hepatotoxicity Eaton, Ph.D.; Leila Gobejishvili, Ph.D.; Swati Joshi after initiation of their HAART treatment, as indicated Barve, Ph.D.; and Craig J. McClain, M.D. by at least a fivefold elevation of liver enzyme levels in HIRISH ARVE H S B , P .D., is the director of Pilot Projects in the Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral University of Louisville Alcohol Research Center; a professor of therapy (HAART) in the 1990s, liver disease is emerging medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and as a major cause of morbidity and mortality among HIV Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Louisville infected patients. This is attributed to a variety of factors, Medical Center; and a joint professor in the Department of including HAART hepatotoxicity, coinfection with Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Louisville, all in hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV, respectively), and alcohol abuse. -

Click the Image Above for the Full Infographic

Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) = the % in your bloodstream. Contrary to popular belief, nothing can lower BAC EXCEPT TIME. BAC can be measured within 30-70 minutes of drinking 1. A PERSON’S BAC CAN VARY 1 % The more you drink, the The faster you drink, the higher your BAC will be. higher your BAC will be. Women tend to have Smaller people have less more body fat, leading water in their body, to a higher BAC. leading to a higher BAC. DELAY Eating before drinking helps to slow alcohol processing, leading to a delayed BAC peak. THE LIMIT Binge drinking means having a BAC of 0.08% or higher 2. The legal BAC threshold for driving is 0.08% or below 3. 0.08 LIMIT WHAT IS A “STANDARD DRINK”? 4 5% 12% 40% 12 oz. Beer 5 oz. Wine 1.5 oz. Liquor Not All Drinks are Equal One drink may have multiple standard drinks in it. % % % % WHAT HAPPENS AS YOU INCREASE YOUR BAC? 1, 5, 6. And How Many Drinks Is That Over the Course of an Evening? 7, 8, 9** 0.00% 0.00% (0 Drinks) Sober and in control 1-4 drinks 1-3 drinks 0.01 - 0.02 Relaxed Mood change 5-6 drinks 3-4 drinks 0.03 - 0.05 Minor reduction in muscle control and coordination Slight speech, memory, and attention impairment Exaggerated emotions and behaviors Light drowsiness 6-7 drinks 4-5 drinks 0.06 - 0.08 0.06 - 0.08 Speech, memory, attention, and coordination problems become more noticeable Sense of increased confidence Impaired vision and hearing Difficulty concentrating 8-9 drinks 6-7 drinks 0.09 - 0.10 Poor reaction time Poor self-control Moderate memory problems Poor depth perception 12-14 drinks 8-10 -

A Small Dose of Alcohol Introduction

From the Toxipedia website in original form. Last updated by Toxipedia in 2011. Dr. Steve Gilbert, author. A Small Dose of Alcohol Introduction Viewed through the lens of toxicology, alcoholic beverages provide a fascinating window into our relationship with a substance that many of us consume because of its intoxicating properties. Our relationship with alcoholic beverages began over 10,000 years ago with the accidental fermentation of grain. But despite our great familiarity with the use of alcohol, it was not until the early 1970s that we realized that alcohol consumption during pregnancy severely affected the developing infant, with no apparent harm to the mother. Worldwide, 9.1 infants per 1000 are affected by Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). The word alcohol comes from the Arabic al-kuhul originally referring to a white powder of antimony used as eye makeup. It was not until the middle of the 18th century that alcohol took on its current meaning of the fermented and intoxicating ingredient found in many common beverages. Fermentation occurs when microorganisms such as yeast, fungi, or bacteria break down complex molecules to produce energy in the absence of oxygen. During fermentation, certain strains of yeast produce ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide in their quest for energy from available sugars. Below is a list of common fermentation starting points and the end products either as a direct result of fermentation of from further distillation. • Cereal grains -> Beers and whiskeys • Honey -> Mead • Grapes -> Wine and brandy • Root vegetables -> Vodka • Sugar cane -> Rum Alcohol is also an excellent and widely used solvent, appearing in many products from gasoline todrugs. -

A Title 4 Off-Sale Basic Training Provider Approved by the Arizona Department of Liquor Licenses and Control

AACEA Welcome to America’s Alcohol Certified Education Association, Inc; a Title 4 Off-Sale Basic Training Provider approved by the Arizona Department of Liquor Licenses and Control. AACEA is a group of Hospitality Industry Professionals who are well versed in all aspects of Alcohol Sales and Service. The founder of AACEA is considered to be an "Expert" in the field of Alcohol Service amongst the legal community. Our philosophy is to provide Alcohol Server Education focused on customer safety by Promoting Responsible Alcohol Sales and Service. You can be assured that with AACEA you will be given quality information to help you in your employment as a seller server of alcohol. Thank you so much for choosing AACEA for your online training. The Arizona DLLC requires that all persons who work in the capacity of an alcohol seller, server, bartender etc. know the laws pertaining to Spirituous Liquor sales and service. The best way to ensure this is to attend an approved Title 4 training seminar. In fact some employers, for the condition of employment, require this training in order to be considered for a job at their establishment. You as an employee, of either an on-sale licensed location, or an off-sale licensed location have a responsibility to your customers and to your establishment to maintain a safe environment. This fact is taken so seriously that a liquor license could be revoked if the licensee or staff doesn’t take reasonable steps to protect the customer. The tools you will need to accomplish this will be learned in this seminar. -

N-Squad Episode Two: Mission Debrief

N-Squad Episode Two: Mission Debrief TEACHER VERSION These short answer response questions can be used as a review or as a fi nal assessment or both. Review Arrange your students in groups of four to six. Have them choose a recorder who will fi rst guide the group in brainstorming all the key points they felt they learned in the episode they just played. Then, hand them the questions from that episode. They may choose one of the questions or you may have them draw for one. If time permits, you could have the group respond to both. Provide each student with a copy of the question since it includes the terms they are trying to use. As a group, they should submit a written response to the question. The discussion of the terms and the explanation of defi nitions and concepts by the students will be an excellent review. The group can receive credit for both their brainstorming list and the fi nal written response. Assessment To use as a fi nal assessment, have students choose between the questions and write their response. Encourage them to use the terms that are included. Question 1 Explain the BAC level and identify how various factors might affect the level of alcohol in the blood. Use these terms in your answer: male, female, weight, servings per hour, and metabolism rate. Answer BAC (blood alcohol concentration, or blood alcohol content) is the percent of alcohol in a person’s bloodstream. The higher the BAC, the more drunk a person is. One factor that can affect the level of alcohol in the blood is gender. -

05 BAC Research Facts

Studies on the Effectiveness of .05 BAC Visit MADD.ORG/05 for more information .05 BAC Research Facts .05 BAC saves lives • If all states implemented a .05 BAC level, 538 to 1,790 lives would be saved each year. (Wagenaar, 2007) (Fell, 2018). • If .05 BAC is implemented in the U.S., alcohol-related fatalities would decrease by 11.1 percent. (Fell, 2018) • Reduces alcohol-related deaths from 5 to 18 percent. (Mann et al, 2001, Fell & Voas, 2006, NTSB 2017). (Fell, 2017) (Bartl, 2002) (Mercier-Guyon, 1998) (Henstridge, 1997) (Norstrom, 1997) (Smith, 1996) (Noordzij, 1994) Driving at a .05 BAC increases crash risk significantly • For drivers with BACs of .05–.079, the risk of being in a fatal crash (single-vehicle) is at least seven times higher than for drivers with no alcohol in their system. (Zador et al 2000, NIH/NIAAA Alcohol Alert 2001, Voas et al 2012, NTSB, 2017). • At .05, crash risk is 38 to 40 percent higher than it is at zero alcohol concentration. (National Safety Council, 2016). (Compton, 2002). • Risk of being killed as a driver in a single vehicle crash is 6 to 17 times greater for drivers at BACs between .05 and .07 compared to drivers with .00 BACs. (Zador, 2000) In the United States, a majority of the public supports a .05 BAC • 63 percent of people support lowering the illegal BAC level from .08 to .05. (AAA Foundation, 2015). Research on .05 BAC Fell, James, Presentation at 2018 Lifesavers Conference, San Antonio, TX, “Rationale for Lowering the BAC Limit to .05 in the US,” April 22-24, 2018.