The Role of Policy in the Great Recession and the Weak Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Crisis Theory and the Severity of the Current Economic Crisis

Marxist Crisis Theory and the Severity of the Current Economic Crisis By David M. Kotz Department of Economics Thompson Hall University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, MA 01003, U.S.A. December, 2009 Email Address: [email protected] This paper was presented on a panel on "Heterodox Analyses of the Current Economic Crisis" sponsored by the Union for Radical Political Economics at the Allied Social Science Associations annual convention, Atlanta, January 4, 2010. Research Assistance was provided by Ann Werboff. It is a revised version of a paper "The Final Crisis: What Can Cause a System-Threatening Crisis of Capitalism," Science & Society 74(3), July 2010. Marxist Crisis Theory and the Current Crisis, December, 2009 1 The theory of economic crisis has long occupied an important place in Marxist theory. One reason is the belief that a severe economic crisis can play a key role in the supersession of capitalism and the transition to socialism. Some early Marxist writers sought to develop a breakdown theory of economic crisis, in which an absolute barrier is identified to the reproduction of capitalism.1 However, one need not follow such a mechanistic approach to regard economic crisis as central to the problem of transition to socialism. It seems highly plausible that a severe and long-lasting crisis of accumulation would create conditions that are potentially favorable for a transition, although such a crisis is no guarantee of that outcome.2 Marxist analysts generally agree that capitalism produces two qualitatively different kinds of economic crisis. One is the periodic business cycle recession, which is resolved after a relatively short period by the normal mechanisms of a capitalist economy, although since World War II government monetary and fiscal policy have often been employed to speed the end of the recession. -

Price Spike Of

United States Department of The "Great" Price Spike of '93: Agriculture Forest Service An Analysis of Lumber and Pacific Northwest Research Station Stum.page Pr=ces =n the Research Paper PNW-RP-476 Pac=f=c Northwest August 1994 Brent L. Sohngen and Richard W. Haynes ....~ ~i!i I 11~.............. pp~L~ ~ S if!i,: ~SS ~$~ ~ ~ S$ $ $_ ss sSSos'S S$ $ S$$ s$$SsSss s ss $ sss~ ~ S sSsS~ Sss S $~ $.~ $ S$ Authors BRENT L. SOHNGEN is a graduate student, Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, CT 06510; and RICHARD W. HAYNES is a research forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, P.O. Box 3890, Portland, OR 97208-3890. Abstract Sohngen, Brent L.; Haynes, Richard W. 1994. The "great" price spike of '93: an analysis of lumber and stumpage prices in the Pacific Northwest. Res. Pap. PNW-RP-476. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 20 p. Lumber prices for coast Douglas-fir (Psuedotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco var. menziesil) swung rapidly from a low of $306 per thousand board feet (MBF) in September 1992 to a high of $495/MBF in March 1993. This price spike represented a sizable increase in the value of lumber over a short period, but it was not the histor- ical anomaly that many in the media would suggest. Using the theoretical relation between lumber and stumpage prices, we analyzed the interaction between these two markets over the past 82 years. Among our major findings were that there are distinct seasonal variations in monthly lumber and stumpage prices; over the longer term, these markets can be divided into three different periodsm1910 to 1944, 1945 to 1962, and 1963 to 1992; the most recent price spike did not match previous spikes in real terms; and the traditional lumber and stumpage price interaction became more significant with time but it does not seem to be as pronounced when we look at monthly prices. -

The UK Recession in Context — What Do Three Centuries of Data Tell Us?

Research and analysis The UK recession in context 277 The UK recession in context — what do three centuries of data tell us? By Sally Hills and Ryland Thomas of the Bank’s Monetary Assessment and Strategy Division and Nicholas Dimsdale of The Queen’s College, Oxford.(1) The Quarterly Bulletin has a long tradition of using historical data to help analyse the latest developments in the UK economy. To mark the Bulletin’s 50th anniversary, this article places the recent UK recession in a long-run historical context. It draws on the extensive literature on UK economic history and analyses a wide range of macroeconomic and financial data going back to the 18th century. The UK economy has undergone major structural change over this period but such historical comparisons can provide lessons for the current economic situation. Introduction An overview of UK business cycles The UK economy recently suffered its deepest recession since Over the past half century, enormous effort has gone into the 1930s. The recent recession had several defining constructing historical national income data for the characteristics: it took place simultaneously with a global United Kingdom. First, annual GDP estimates were recession; the financial sector was both the source and constructed back to the mid-19th century, based on output, propagator of the crisis; the exchange rate depreciated income and expenditure approaches (Deane and Cole (1962), sharply; and there was a substantial loosening of monetary Deane (1968) and Feinstein (1972)). These were followed by policy alongside a marked increase in the fiscal deficit. But ‘balanced’ estimates of GDP growth that attempted to despite UK output falling by more than 6% between 2008 Q1 reconcile these different approaches from 1870 onwards and 2009 Q3, CPI inflation remains above the Government’s (Solomou and Weale (1991) and Sefton and Weale (1995)). -

The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment Mary Daly Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Bart Hobijn Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Rob Valletta Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco January 2011 Working Paper 2011-05 http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2011/wp11-05bk.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment MARY DALY,* BART HOBIJN, AND ROB VALLETTA Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 101 Market Street San Francisco, CA 94105 January 17, 2011 ABSTRACT The U.S. economy is recovering from the financial crisis and ensuing deep recession, but the unemployment rate has remained stubbornly high. Some have argued that the persistent elevation of unemployment relative to historical norms reflects the fact that the shocks that hit the economy were especially disruptive to labor markets and likely to have long lasting effects. If such structural factors are at work they would result in a higher underlying natural or non- accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, implying that conventional monetary and fiscal policy should not be used in an attempt to return unemployment to its pre-recession levels. We investigate the hypothesis that the natural rate of unemployment has increased since the recession began, and if so, whether the underlying causes are transitory or persistent. -

Framing the Global Economic Downturn Crisis Rhetoric and the Politics of Recessions

Framing the global economic downturn Crisis rhetoric and the politics of recessions Framing the global economic downturn Crisis rhetoric and the politics of recessions Edited by Paul ’t Hart and Karen Tindall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/global_economy_citation. html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Framing the global economic downturn : crisis rhetoric and the politics of recessions / editor, Paul ‘t Hart, Karen Tindall. ISBN: 9781921666049 (pbk.) 9781921666056 (pdf) Series: Australia New Zealand School of Government monograph Subjects: Financial crises. Globalization--Economic aspects. Bankruptcy--International cooperation. Crisis management--Political aspects. Political leadership. Decision-making in public administration. Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t Tindall, Karen. Dewey Number: 352.3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Cover images sourced from AAP Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2009 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University and is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). He is also a joint appointment with the Department of Politics and Public Policy at Griffith University and a principal researcher with two research centres: the Governance and Public Policy Research Centre and the nationally-funded Key Centre in Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance at Griffith University. -

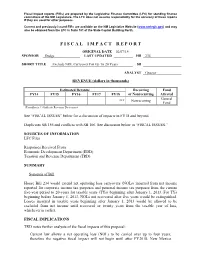

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current and previously issued FIRs are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov) and may also be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/14 SPONSOR Dodge LAST UPDATED HB 234 SHORT TITLE Exclude NOL Carryover For Up To 20 Years SB ANALYST Graeser REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Estimated Revenue Recurring Fund FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 or Nonrecurring Affected General *** Nonrecurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decreases) See “FISCAL ISSUES” below for a discussion of impacts in FY18 and beyond. Duplicates SB 156 and conflicts with SB 106. See discussion below in “FISCAL ISSUES.” SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Economic Development Department (EDD) Taxation and Revenue Department (TRD) SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 234 would extend net operating loss carryovers (NOLs) incurred from net income reported for corporate income tax purposes and personal income tax purposes from the current five-year period to 20-years for taxable years (TYs) beginning after January 1, 2013. For TYs beginning before January 1, 2013, NOLs not recovered after five years would be extinguished. Losses incurred in taxable years beginning after January 1, 2013 would be allowed to be excluded from net income until recovered or twenty years from the taxable year of loss, whichever is earlier. -

Reflections on Australia's Era of Economic Reform

Reflections on Australia’s era of economic reform* Address to the European Australian Business Council Dr Martin Parkinson PSM, Secretary to the Treasury 5 December 2014, Sydney * I would like to express my appreciation to Jason Allford, Bryn Battersby, Luke Willard, Jenny Wilkinson, Christiane Gerblinger and Marty Robinson for their assistance in preparing these remarks. Due to time constraints, a summary version of this speech was delivered to the EABC. It’s yet again a huge pleasure to be with the European Australian Business Council. I have spoken here on a number of occasions and have always enjoyed these engagements. Perhaps unsurprisingly, today I’m in the frame of mind to reflect a little on the some of the major economic reforms that have happened over the course of my career, and how they have affected the Australian economy. So, as they say in the classics, let’s start in the beginning. I first joined the Treasury more than three decades ago. For me, it was a temporary stop on the path to becoming an academic. Working for the public service was a means of gaining some experience — and some cash — before going on to do further studies. If you had told me in 1981 that I would stay on long enough to be able to speak to you tonight as Treasury Secretary, then I would have been shocked. I dare say John Stone, the Secretary at the time, would have been shocked as well! Of course, I have managed in those 30-something years to get out of the Treasury building and do a few other things. -

Monetary Policy and the Current Recession

Monetary Policy and the Current Recession Speech given by Andrew Sentence, Member of the Monetary Policy Committee, Bank of England At the Institute of Economic Affairs’ 26th Annual State of the Economy Conference 24 February 2009 I would like to thank Michael Hume and Abigail Hughes for research assistance and I am also grateful for helpful comments from other colleagues. The views expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of England or other members of the Monetary Policy Committee. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/default.aspx 2 I am delighted to have the opportunity to speak at this year’s IEA State of the Economy conference. But I don’t think anyone could express much delight or pleasure about the short-term prospects for the UK economy or other major economies around the world at present. The economic backdrop to this year’s conference must be one of the most gloomy since this series of conferences began in the late 1980s. The UK economy is in recession – along with other major economies. The British economy has already experienced two quarters of falling GDP in the second half of last year and business surveys suggest this contraction is continuing in the first half of this year. The February Consensus Forecast was for a contraction of UK GDP of 2.6% in 2009 as a whole. The Bank of England’s central projection published in this month’s Inflation Report is a little weaker than this, with GDP projected to fall on average by about 3% in 2009. -

Australia's Experience with Economic Reform

AUSTRALIA’S EXPERIENCE WITH ECONOMIC REFORM Laura Berger-Thomson, John Breusch and Louise Lilley1 Treasury Working Paper October 2018 This paper has been prepared to inform an officials level workshop at the IMF and World Bank Annual Meetings in Bali, Indonesia in October 2018. The paper will be discussed by Ms Laura Berger-Thomson and a panel including Dr Changyong Rhee, Mr Charles Abel, Dr Mohamad Chatib Basri, Mr Rodrigo Valdés and Mr Nigel Ray. This paper discusses the factors and circumstances that influenced the course of the Australian economy over the past 40 years. It will discuss challenges Australia faced and events that motivated reform emphasising aspects unique to Australia as a commodity exporting country, geographically remote with a relatively small population. 1 The authors are from the Macroeconomic Group, The Treasury, Langton Crescent, Parkes ACT 2600, Australia. Correspondence: Laura Berger-Thomson, [email protected]. We thank Cassandra Switaj and Karen Moorcroft for excellent research assistance, participants at a number of seminars at The Treasury, the Reserve Bank of Australia, Nigel Ray and other referees for their useful comments. This paper has also benefited greatly from feedback from academics and senior policy advisers, including some with first-hand experience of the reform process and its effects. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Australian Treasury or the Australian Government. © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 This publication is available for your use under a Creative Commons BY Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, the Treasury logo, photographs, images, signatures and where otherwise stated. -

Do Factors Carry Information About the Economic Cycle? Part 2: New Thinking: Rebooting the Investment Clock for the New Normal and QE Regime

Market Navigation Factor Analysis/Smart Beta Do factors carry information about the economic cycle? Part 2: New thinking: Rebooting the Investment Clock for the new normal and QE regime January 2021 AUTHOR Overview Marlies van Boven, PhD Head of Investment Research, Institutional investors often pose the question of how factors perform across EMEA economic cycles. The concept of a normalized cycle has come under pressure +44 20 7866 1853 in the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) era that has seen sustained [email protected] quantitative easing (QE), financial repression and lower trend growth. Consequently, this has necessitated a reappraisal of the traditional Investment Clock. In this paper, we focus on the new thinking, rebooting the Investment Clock to link factor behavior to secular regime shifts in the US market. • The Investment Clock’s analysis [1] is predicated on the notion of a discernible economic or business cycle whose existence is questionable post GFC due to quantitative easing. • An evolution of the Investment Clock is to observe a pattern of secular regime shifts. • We find that regimes have a significant impact on factor payoffs, driven by the level and volatility of economic indicators. • Since the GFC, below trend growth and inflation have oscillated in an all- time narrow range and have proven to be a difficult environment for broad- based factor performance. • If the past is any indication of the future a more favorable environment for diversified factor investing is trend economic growth and target inflation. ftserussell.com 1 Contents Introduction 3 1. New thinking: Rebooting the Investment Clock for the new normal and QE regime 4 Regime 1: 1970s’ high inflation and early 1980s’ recession (1974 to 1982) 6 Regime 2: Great Moderation (1983 to 1995) 7 Regime 3: Goldilocks (1996 to 2005) 7 Regime 4: Global Financial Crisis and quantitative easing (2007 to 2014) 8 Regime 5: Normalization: unwinding quantitative easing and Covid-19 (2015 to 2020) 9 2. -

The Labor Market in the Great Recession

12178-01a_Elsby_rev4.qxd 8/11/10 12:06 PM Page 1 MICHAEL W. L. ELSBY University of Michigan BART HOBIJN Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco AYS¸EGÜL ¸AHIS ·N Federal Reserve Bank of New York The Labor Market in the Great Recession ABSTRACT From the perspective of a wide range of labor market out- comes, the recession that began in 2007 represents the deepest downturn in the postwar era. Early on, the nature of labor market adjustment displayed a notable resemblance to that observed in past severe downturns. During the lat- ter half of 2009, however, the path of adjustment exhibited important depar- tures from that seen during and after prior deep recessions. Recent data point to two warning signs going forward. First, the record rise in long-term un- employment may yield a persistent residue of long-term unemployed workers with weak search effectiveness. Second, conventional estimates suggest that the extension of Emergency Unemployment Compensation may have led to a modest increase in unemployment. Despite these forces, we conclude that the problems facing the U.S. labor market are unlikely to be as severe as the Euro- pean unemployment problem of the 1980s. ince December 2007, labor market conditions in the United States Shave deteriorated dramatically. The depth and duration of the decline in economic activity have led many to refer to the downturn as the “Great Recession.” In this paper we document the adjustment of the labor market during the recession and place it in the broader context of previous postwar 1 12178-01a_Elsby_rev4.qxd 8/11/10 12:06 PM Page 2 2 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2010 downturns. -

Living Standards During Previous Recessions

Living Standards During Previous Recessions IFS Briefing Note BN85 Alastair Muriel Luke Sibieta Living standards during previous recessions Alastair Muriel and Luke Sibieta* Institute for Fiscal Studies 1. Introduction The current recession is the first that the UK has experienced since the early 1990s. Much has changed since then, and society’s collective memory of who fared worst during previous recessions seems likely to have faded. Many workers in their 20s or early 30s have not experienced a recession during their working lives – including both authors of this report, one of whom had just started secondary school at the end of the last recession and the other of whom had just started junior school. This Briefing Note thus aims to document the course of average living standards, and those of particular subgroups in society, during the previous three UK recessions. It will also show what happened to measures of poverty and inequality during these periods. Given that recessions vary in their origins, such a backward-looking approach still leaves us guessing as to the likely effects of the current recession on living standards and poverty. However, the experience of * The authors are very grateful for financial support from the Nuffield Foundation for the project ‘Poverty and Inequality: 2007–2009’, project number OPD/33941.The Nuffield Foundation is a charitable trust established by Lord Nuffield. Its widest charitable object is ‘the advancement of social well-being’. The Foundation has long had an interest in social welfare and has supported this project to stimulate public discussion and policy development. Co-funding from the ESRC-funded Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS (grant number M535255111) is also very gratefully acknowledged.