Crowdfunding As a Marketing Toll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LTG Pool.Xlsx

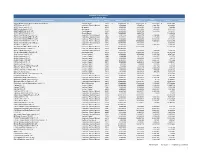

Long-Term Growth Pool Asset Allocation & Expenses As of July 2013 45% Equity Target Allocation Fee (%) 100% 17% US. Large Capitalization Vanguard 500 5.1% 0.05 Adage Capital 3.4% 0.50 Dodge & Cox 4.3% 0.52 U.S. Large Cap Touchstone Sands Instl Growth 2.1% 0.75 90% Capital Counsel 2.1% 0.80 4% U.S. Mid Capitalization Times Square 2.0% 0.80 U.S. Mid Cap Cooke & Bieler 2.0% 0.79 80% 4% U.S. Small Capitalization U.S. Small Cap Advisory Research 2.0% 1.00 Artisan Partners 2.0% 1.00 10% International Developed Markets International 70% Artisan Partners 3.0% 1.00 Equity Silchester 3.0% 0.98 Gryphon International 3.0% 0.90 Vanguard 1.0% 0.07 Emerging 5% Emerging Markets Markets Westwood Global 3.0% 1.25 60% Opportunistic/ Dimensional Fund Advisors 2.0% 0.62 Special Situation 5% Opportunistic/Special Situation Various managers and strategies 5.0% 1.50 U.S. Aggregate 50% 25% Fixed Income Bonds 10% U.S. Aggregate Bonds PIMCO Total Return 5.0% 0.46 Income Research & Management 5.0% 0.35 TIPS 4% Treasury Inflation Protected Securities 40% Vanguard 4.0% 0.09 U.S. High Yield 4% US High Yield Bonds Post Advisory 4.0% 0.75 Global Bonds 7% Global Bonds Colchester Global 3.5% 0.55 30% GMO 3.5% 0.43 Direct Hedge 30% Alternatives1 Funds 9% Direct Hedge Funds Various managers and strategies 9.0% 1.50 20% Fund of Hedge 6% Fund of Hedge Funds Funds Various managers and strategies 6.0% 1.00 2 5% Private Equity Private Equity Various managers and strategies 5.0% 1.75 10% 5% Private Real Assets/Real Estate Real Assets Various managers and strategies 5.0% 2.00 Real Estate 5% Commodities Wellington 5.0% 0.90 Commodities 0% Asset Weighted Total 100% 0.89 Custodian Bank 0.03 Investment Consulting and Administration 0.07 Total Investment Expenses* 0.99 1 Expenses shown do not include carried interest or the expense of individual managers within fund of funds. -

HIERS Performance Report by Investment

Statement of Investments (1) As of June 30, 2017 Total Investment Name Investment Strategy Vintage Committed Paid-In Capital (2) Valuation Net IRR Distributions Abraaj Global Growth Markets Strategic Fund, L.P. Growth Equity 2015 $ 45,000,000 $ 30,442,233 $ 6,226,973 $ 34,191,582 ABRY Partners VII, L.P. Corporate Finance/Buyout 2011 3,500,000 3,569,519 3,861,563 2,239,428 ABRY Senior Equity III, L.P. Mezzanine 2010 5,000,000 4,618,602 7,138,392 322,958 ABRY Senior Equity IV, L.P. Mezzanine 2012 6,503,582 6,227,869 1,900,948 6,205,777 ABS Capital Partners VI, L.P. Growth Equity 2009 4,000,000 3,906,193 1,775,815 1,812,911 ABS Capital Partners VII, L.P. Growth Equity 2012 10,000,000 9,054,134 - 11,860,984 Advent International GPE V-B, L.P. Corporate Finance/Buyout 2012 2,801,236 2,583,570 3,290,856 248,977 Advent International GPE V-D, L.P. Corporate Finance/Buyout 2005 3,179,324 3,038,405 7,175,404 245,538 Advent International GPE VI-A, L.P. Corporate Finance/Buyout 2008 9,500,000 9,500,000 14,172,848 5,876,065 Advent International GPE VII-B, L.P. Corporate Finance/Buyout 2012 30,000,000 27,000,000 11,400,028 32,412,380 Advent International GPE VIII-B, L.P. Corporate Finance/Buyout 2016 36,000,000 8,424,000 - 8,986,703 Alta Partners VIII, L.P. -

UMB Annual Report

We are building a company for the next 100 years. 2012 ANNUAL REPORT Industry UMBF Data from SNL Financial as of 12/31/12 UMB Financial Corporation A diversified financial services company. As of 12/31/12 -16.0% +115% Dividend Growth Dividend Growth July 2003 through 12/31/12 UMB increased its quarterly dividend 4.9 percent in 2012, the 12th time since July 2003, a total increase of 115 percent. 2.28% .49% Nonperforming Loans To Total Loans Nonperforming Loans To Total Loans UMB has maintained high asset quality through all kinds of economic conditions. 77.9% 48.8% Loans-To-Deposits Ratio Loans-To-Deposits Ratio We are in the business of lending money and have plenty of liquidity to meet our customers’ needs. 14.3% 11.1% Tier 1 Capital Ratio Tier 1 Capital Ratio Unlike the industry, our Tier 1 capital ratio remains strong without government intervention or dilutive capital actions. +15.5% +46.5% Noninterest Income Growth Noninterest Income Growth During the past five years. Our noninterest income over the last five years again outpaced the industry, demonstrating that our diversified business model remains effective. Our business isn’t about money, it’s about trust. Trust can’t be bought, or sold, or traded. It can only be earned. Day by day, year after year, generation upon generation. That’s why our anniversary is about much more than 100 years. It’s about our roots. It’s about our wings. It’s about our future. A future every one of us will share. UMB, more than 100. -

Cabbies Driven to Stall Uber, Lyft Authority Over Taxi-Cab Services

20140414-NEWS--1-NAT-CCI-CL_-- 4/11/2014 2:55 PM Page 1 $2.00/APRIL 14 - 20 2014 Cabbies driven to stall Uber, Lyft authority over taxi-cab services. In- Ride services steered by smart phone apps say it’s sour grapes stead, Cleveland — at least at the EDITORIAL: Critics of Uber and Lyft moment — considers them limou- need to pump the brakes. Page 10 By TIMOTHY MAGAW last week, but a handful of local cab trance into the market and the is- sine services, which are regulated [email protected] operators hope the city puts the sues that, at least in their opinion, by the state. year, Keenan said his company brakes on the controversial services. could rear their head. Because of That creates an unfair advantage, spent almost $14,000 in licensing Two popular ride-hailing smart Local cabbies say they’ve warned the way the tech companies are according to Patrick Keenan, gen- fees on his roughly 90 cabs in the phone apps — Uber and Lyft — city officials for more than a year structured, they appear to fall eral manager of Americab Trans- city. launched in the Cleveland market about Uber and Lyft’s likely en- largely outside the city’s regulatory portation Inc. in Cleveland. Last See CABBIES Page 19 HE ISN’T DIFFICULT TO FIND Only now, Hanlin’s popular golf shows will be available across the country By KEVIN KLEPS [email protected] or golf fans in Northeast Ohio, Jimmy Hanlin is as ubiquitous as Cleveland Browns draft chatter, Chief FWahoo debates or pleas for LeBron James to return home. -

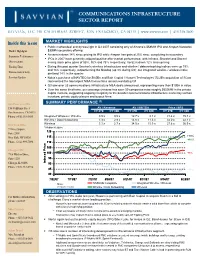

Communications Infrastructure Sector Report

COMMUNICATIONS INFRASTRUCTURE SECTOR REPORT SAVVIAN, LLC 150 CALIFORNIA STREET, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94111 | www.savvian.com | 415.318.3600 MARKET HIGHLIGHTS Inside this issue MARKETMARKET HIGHLIGHTSHIGHLIGHTS Public market deal activity was light in Q3 2007 consisting only of Airvana’s $58MM IPO and Airspan Networks’ Market Highlights $30MM secondary offering Airvana is down 14% since pricing its IPO while Airspan has gained 25% since completing its secondary Summary Performance IPOs in 2007 have generally enjoyed positive after-market performance, with Infinera, Shoretel and Starent Observations seeing stock price gains of 55%, 36% and 76% respectively; Veraz is down 12% since pricing Trading Data During this past quarter Savvian's wireless infrastructure and wireline / data networking indices were up 19% and 16% respectively, outperforming the Nasdaq (up 3% during Q3); our integrated wireline / wireless index Transaction Activity declined 14% in the quarter Savvian Update Nokia’s purchase of NAVTEQ for $8.0Bn and Bain Capital / Huawei Technologies’ $2.2Bn acquisition of 3Com represented the two largest M&A transactions announced during Q3 Q3 saw over 25 communications infrastructure M&A deals announced, representing more than $13Bn in value Over the same timeframe, our coverage universe has seen 50 companies raise roughly $650MM in the private capital markets, suggesting ongoing receptivity to the broader communications infrastructure market by venture investors, private equity players and buyout firms (1) San Francisco Office -

Stanford University's Economic Impact Via Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Impact: Stanford University’s Economic Impact via Innovation and Entrepreneurship October 2012 Charles E. Eesley, Assistant Professor in Management Science & Engineering; and Morgenthaler Faculty Fellow, School of Engineering, Stanford University William F. Miller, Herbert Hoover Professor of Public and Private Management Emeritus; Professor of Computer Science Emeritus and former Provost, Stanford University and Faculty Co-director, SPRIE* *We thank Sequoia Capital for its generous support of this research. 1 About the authors: Charles Eesley, is an assistant professor and Morgenthaler Faculty Fellow in the department of Management Science and Engineering at Stanford University. His research interests focus on strategy and technology entrepreneurship. His research seeks to uncover which individual attributes, strategies and institutional arrangements optimally drive high growth and high tech entrepreneurship. He is the recipient of the 2010 Best Dissertation Award in the Business Policy and Strategy Division of the Academy of Management, of the 2011 National Natural Science Foundation Award in China, and of the 2007 Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation Dissertation Fellowship Award for his work on entrepreneurship in China. His research appears in the Strategic Management Journal, Research Policy and the Journal of Economics & Management Strategy. Prior to receiving his PhD from the Sloan School of Management at MIT, he was an entrepreneur in the life sciences and worked at the Duke University Medical Center, publishing in medical journals and in textbooks on cognition in schizophrenia. William F. Miller has spent about half of his professional life in business and half in academia. He served as vice president and provost of Stanford University (1971-1979) where he conducted research and directed many graduate students in computer science. -

1 Strengthening Science, Technology, and Innovation-Based Incubators To

Strengthening science, technology, and innovation-based incubators to help achieve Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons from India Kavita Surana1*, Anuraag Singh2, Ambuj Sagar2,3 1School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, College Park, USA 2 DST Centre for Policy Research, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, India 3 School of Public Policy, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, India *corresponding author Abstract Policymakers in developing countries increasingly see science, technology, and innovation (STI) as an avenue for meeting sustainable development goals (SDGs), with STI-based startups as a key part of these efforts. Market failures call for government interventions in supporting STI for SDGs and publicly-funded incubators can potentially fulfil this role. Using the specific case of India, we examine how publicly-funded incubators could contribute to strengthening STI-based entrepreneurship. India’s STI policy and its links to societal goals span multiple decades—but since 2015 these goals became formally organized around the SDGs. We examine why STI-based incubators were created under different policy priorities before 2015, the role of public agencies in implementing these policies, and how some incubators were particularly effective in addressing the societal challenges that can now be mapped to SDGs. We find that effective incubation for supporting STI-based entrepreneurship to meet societal goals extended beyond traditional incubation activities. For STI-based incubators to be effective, policymakers must strengthen the ‘incubation system’. This involves incorporating targeted SDGs in specific incubator goals, promoting coordination between existing incubator programs, developing a performance monitoring system, and finally, extending extensive capacity building at multiple levels including for incubator managers and for broader STI in the country. -

3Com Corporation 3Mgives 4Charity Com.Inc. Abbott Laboratories

3Com Corporation Allied Corporation Foundation 3Mgives Allied World Assurance Company 4Charity Com.Inc. Allstate Giving Campaign Abbott Laboratories Altera Corporation Accenture Altria Group, Inc. ACCO Brands Corporation ALZA Corporation ACE Charitable Foundation AMD Foundation Act Now Productions American Express Acxiom Corporation American Express Foundation Adams Street Partners LLC American International Group, Inc. Adaptec, Inc. American President Companies Adelante Capital Management LLC Ameriprise Financial, Inc. Adobe Systems, Inc. Ameritech Advanced Fibre Communications Amgen Foundation Advent Employee Engagement Fund Ampex Corporation AES Corporation Analog Devices Aetna Foundation, Inc. Anchor Brewing Company Agilent Technologies Foundation Andersen Tax Aimco, Inc. Andvari, Inc. Air Products & Chemicals Inc. Andy Corporation Alaska Airlines Annual Reviews Alco Standard Foundation Aon Foundation Alex Brown & Sons, Inc. APL Limited Foundation Alexander & Baldwin, Inc. Apple, Inc. Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Applera Corporation Alliance Data Applied Materials Alliance Bernstein Capital Mgmt Arch Insurance Corporation ARCO Foundation Alliant Techsystems Argo Group US Allianz Global Risks – US Arkwright Foundation, Inc. Armco Foundation Bayshore Global Management, LLC Art.Com Inc. BEA Systems Foundation Arthur J Gallagher Foundation BearingPoint Charitable Foundation Arthur J. Gallagher Foundation Beatrice Foods Co. Aspect Becton Dickinson & Company Aspect Global Giving Program Bell Atlantic Foundation Assurant Foundation Bell-Carter Foods, Inc. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP Berkeley Systems, Inc. AT&T Foundation Berry Appleman & Leiden LLP Atlantic Richfield Birkenstock Footprint Sandals, Inc. Atlassian Software Systems, inc. Bite Communications Corporation ATMI Matching Gifts Program BitMover, Inc. atron Char. Trust BlackRock, Inc. Autodesk Foundation Employee Blauvelt Demarest Foundation, Inc. Engagement Fund Blue Shield of California Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Boeing Company Avaya Communication Boston Consulting Group, Inc. -

Special Report Top 100 Investors

ON TOP OF THE DEALS. IN TOUCH WITH THE DEALMAKERS SPECIAL REPORT TOP 100 INVESTORS EUROPEAN SUPER LEAGUE EVOLVES GERMAN PLAYERS DIVERSIFY SWISS TARGET GERMANY DUTCH BATTLE AGAINST BAD IMAGE RANKING & PROFILES MARCH 2013 The link between property and finance™ Catella is a market leading advisor on the European real estate market. In 2012, we advised in transactions valued at EUR 5.8 billion. We offer financial advisory services within; Sales & Acquisitions Debt & Equity Valuation & Research Catella advised DNB Liv in the sale of 133,000 sq.m. shopping centre Kista Galleria in Stockholm. It was the single largest transaction on the Swedish market and an example of the many top market transactions carried out by Catella in 2012. Catella's real estate advisory operations span Europe with operations established in eleven European countries and more than 200 real estate professionals employed. Our sense of innovation and detailed market expertise let us find solutions that meet the ever changing needs of our clients. That’s what makes us the Link between Property and Finance™. catellaproperty.com DENMARK | ESTONIA | FINLAND | FRANCE | GERMANY | LATVIA | LITHUANIA | NORWAY | SPAIN | SWEDEN | UK Annons PropertyEU Investor Guide 2013.indd 2 04/03/2013 12:53:20 CONTENTS A piece of the pie Who are the biggest investment managers in Europe? Where are they based and what are the sources of new capital flows? This special supplement provides insight into the key players and trends Europe’s super league PropertyEU is proud to present the Top 100 investment managers in Europe in our special Mipim edition. Despite the grim economic cli- mate, there are no signs that capital flows into European real estate are about to abate any time soon. -

Private Equity

Private Equity HIGHLIGHTS Trusted by Sophisticated Deal Makers Wilson Sonsini's financial sponsor clients range from some of the largest diversified private equity firms in the world to mid-market, industry-focused investment and buyout funds, as well as earlier-stage investment firms. Breadth of Practice Our attorneys advise on a range of buyout and investment transactions, including public company going-private deals, senior and mezzanine transaction financings, restructurings and recapitalizations, divisional spin-offs and carve outs, PIPEs, private-company buyouts, and VC investments. International Experience Wilson Sonsini has developed a strong and thriving private equity practice in Greater China and neighboring regions with an outstanding record of advising on private equity-sponsored deals and going-private transactions. OVERVIEW Wilson Sonsini provides counsel to leading private equity and growth equity funds, as well as other financial sponsors, in buyout and investment transactions, including: Public company "taking private" or "going private" deals Senior and mezzanine transaction financings Restructurings and recapitalizations Divisional spin-offs and carve outs Private investments in public equity (PIPEs) Private company buyouts Growth and later-stage financings Venture capital investments Various portfolio company transactions Wilson Sonsini financial sponsor clients range from some of the world's largest diversified private equity firms to mid- market, industry-focused investment and buyout funds, as well as earlier-stage investment firms. The firm's private equity clients are sophisticated deal makers who demand creativity, flexibility, differentiated insight, and disciplined and nimble execution from their legal counsel. Our interdisciplinary team of seasoned private equity attorneys in the U.S. and Greater China are experienced at working with financial sponsors in highly competitive markets and the team has consistently helped private equity clients complete successful transactions. -

Consim Info Raises USD 11.75 Million from Mayfield Fund, Yahoo! and Canaan Partners

Press Release Consim Info raises USD 11.75 Million from Mayfield Fund, Yahoo! and Canaan Partners Mayfield Fund, a US based venture capital firm, has joined as a new investor Yahoo! & Canaan Partners have participated in the second round Chennai, February, 6 th 2008: Consim Info Pvt. Ltd, formerly known as BharatMatrimony Group , today announced that it has closed its second round of investment of USD $ 11.75 million led by Mayfield Fund and participation from existing investors, Yahoo! and Canaan Partners. Veda Corporate advisor acted as the strategic advisor for the transaction. The company had earlier raised an initial funding of USD $ 8.65 million in 2006 from Yahoo! and Canaan Partners. Following this development, Nikhil Khattau will join the Board of Consim as Director and Navin Chaddha of Mayfield Fund will be an observer on the Board. Nikhil Khattau, Mayfield Fund said, “We are excited to participate in the tremendous growth that Consim Info has achieved in their Matrimony and Classified businesses. We believe India is poised to see exponential growth in the online classifieds market and that Consim is clearly positioned to be the leader in its field”. Greg Mrva, Vice President, Corporate Development, Yahoo! Inc., said , “Yahoo! is committed to India, and this investment reaffirms our belief in the Indian internet growth prospects, the strength of Consim in the consumer internet space and our confidence in Consim’s management. Alok Mittal, Managing Director, Canaan Partners, India added, “Consim is a leader in the online matrimony business, and we are confident that the additional investment will help it to expand its leadership and range of services. -

CONFIRMED FIRMS American Securities New York, NY American Securities LLC (“American Securi

CONFIRMED FIRMS American Securities New York, NY http://www.american-securities.com/ American Securities LLC (“American Securities” or the “Firm”) was founded as a family office in 1947 to invest a share of the fortune created from Sears, Roebuck & Co. In 1994, the Firm opened its private equity activities to outside investors seeking superior risk-adjusted rates of return. By successfully implementing this strategy, American Securities has grown to manage a series of six private equity funds with approximately $8 billion of aggregate committed capital on behalf of high net worth individuals, families, and institutions, both in the United States and internationally. The Firm’s most recent fund, American Securities Partners VI, L.P., had a final closing in June 2012 on more than $3.6 billion of capital. American Securities is headquartered in New York and also has an office in Shanghai, which supports portfolio companies in their Asia-Pacific activities and the Firm’s due diligence processes generally. American Securities has over 90 employees. The Firm has achieved substantial long-term capital appreciation with minimal operating and financial risk. American Securities strives to be a long-term, value-added partner to the management teams of the companies in which it invests. The Firm offers portfolio companies a unique team of in-house, world-class business and functional experts (the Resources Group). All investments are undertaken with a conservative financial structure consisting of only equity and senior debt. Michael G. Fisch President & CEO In 1994, Mr. Fisch co-founded American Securities LLC, which currently has cumulative committed capital of more than $9 billion.