Egg Allergy: Diagnosis and Immunotherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Allergy Outline

Allergy Evaluation-What it all Means & Role of Allergist Sai R. Nimmagadda, M.D.. Associated Allergists and Asthma Specialists Ltd. Clinical Assistant Professor Of Pediatrics Northwestern University Chicago, Illinois Objectives of Presentation • Discuss the different options for allergy evaluation. – Skin tests – Immunocap Testing • Understand the results of Allergy testing in various allergic diseases. • Briefly Understand what an Allergist Does Common Allergic Diseases Seen in the Primary Care Office • Atopic Dermatitis/Eczema • Food Allergy • Allergic Rhinitis • Allergic Asthma • Allergic GI Diseases Factors that Influence Allergies Development and Expression Host Factors Environmental Factors . Genetic Indoor allergens - Atopy Outdoor allergens - Airway hyper Occupational sensitizers responsiveness Tobacco smoke . Gender Air Pollution . Obesity Respiratory Infections Diet © Global Initiative for Asthma Why Perform Allergy Testing? – Confirm Allergens and answer specific questions. • Am I allergic to my dog? • Do I have a milk allergy? • Have I outgrown my allergy? • Do I need medications? • Am I penicillin allergic? • Do I have a bee sting allergy Tests Performed in the Diagnostic Allergy Laboratory • Allergen-specific IgE (over 200 allergen extracts) – Pollen (weeds, grasses, trees), – Epidermal, dust mites, molds, – Foods, – Venoms, – Drugs, – Occupational allergens (e.g., natural rubber latex) • Total Serum IgE (anti-IgE; ABPA) • Multi-allergen screen for IgE antibody Diagnostic Allergy Testing Serological Confirmation of Sensitization History of RAST Testing • RAST (radioallergosorbent test) invented and marketed in 1974 • The suspected allergen is bound to an insoluble material and the patient's serum is added • If the serum contains antibodies to the allergen, those antibodies will bind to the allergen • Radiolabeled anti-human IgE antibody is added where it binds to those IgE antibodies already bound to the insoluble material • The unbound anti-human IgE antibodies are washed away. -

Egg Allergy: the Facts

Egg Allergy: The Facts Egg is a common cause of allergic reactions in infants and young children. It often begins in the child’s first year of life and in some cases lasts into the teenage years – or even into adulthood for a few people. Children who develop allergy to foods such as egg often have other allergic conditions. Eczema and food allergy often occur in early infancy and later on there may be hay-fever, asthma or both. This Factsheet aims to answer some of the questions which you and your family may have about living with egg allergy. Our aim is to provide information that will help you to understand and minimise risks. Even severe cases can be well managed with the right guidance. Many cases of egg allergy are mild, but more severe symptoms are a possibility for some people. If you believe you or your child is allergic to egg, the most important message is to visit your GP and ask for allergy tests and expert advice on management. Throughout this Factsheet you will see brief medical references given in brackets. If you wish to see the full references, please email us at [email protected]. Symptoms triggered by egg The symptoms of a food allergy, including egg allergy, may occur within seconds or minutes of contact with the culprit food. On occasions there may be a delay of more than an hour. Mild symptoms include nettle rash (otherwise known as hives or urticaria) or a tingling or itchy feeling in the mouth. More serious symptoms are uncommon but remain a possibility for some people, including children. -

Genital Allergy C Sonnex

4 Sex Transm Infect: first published as 10.1136/sti.2003.005132 on 30 January 2004. Downloaded from REVIEW Genital allergy C Sonnex ............................................................................................................................... Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:4–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.005132 Genital allergy should be considered as a possible Local responses consist of genital swelling, burning, irritation, or soreness which may occur diagnosis in all patients with genital soreness or irritation during or soon after intercourse, usually becom- for which no infection or dermatosis can be identified and ing maximal at 24 hours and lasting 2–3 days.45 in whom symptoms remain unchanged or worsen with Semen contact with non-genital skin may also give rise to localised itching and urticaria.67 treatment. Type I and IV hypersensitivity reactions are most Generalised reactions associated with semen commonly encountered and can be assessed by allergy include angioedema of the lips and performing skin prick testing/radioallergosorbent test eyelids,68 laryngeal oedema,9 bronchospasm,10 and anaphylaxis347 but, to date, death has not (RAST) or patch testing, respectively. Type IV reactions been reported. Semen allergy mainly affects (contact dermatitis) may sometimes prove difficult to younger women although postmenopausal cases distinguish clinically from an irritant dermatitis. This clinical are documented.11 12 An increasing intensity of reaction with subsequent episodes of coitus is a review attempts to summarise key features of genital common feature. Levine et al described a married allergy for the practising clinician. woman with a 15 year history of hay fever who ........................................................................... initially presented with swollen eyes, nasal congestion, and sneezing an hour after coitus. -

What You Need to Know

WhatWhat YouYou NeedNeed ToTo KnowKnow 11 inin 1313 childrenchildren That’sThat’s roughlyroughly inin thethe U.S.U.S. hashas 66 millionmillion aa foodfood allergy...allergy... children.children. That'sThat's aboutabout 22 kidskids inin everyevery classroom.classroom. MoreMore thanthan 15%15% ofof schoolschool agedaged childrenchildren withwith foodfood allergiesallergies havehave hadhad aa reactionreaction inin school.school. A food allergy occurs when Food allergy is an IgE-mediated immune the immune system targets a reaction and is not the same as a food food protein and sets off a intolerance or sensitivity. It occurs quickly reaction throughout the body. and can be life-threatening. IgE, or Immunoglobulin E, are antibodies produced by the immune system. IgE antibodies fight allergenic food by releasing chemicals like histamine that trigger symptoms of an allergic reaction. ANTIBODY HISTAMINE Mild Symptoms Severe Symptoms Redness around Swelling of lips, Difficulty Hives mouth or eyes tongue and/or throat swallowing Shortness of Low blood Itchy mouth, Stomach pain breath, wheezing pressure nose or ears or cramps Loss of Chest pain consciousness Nausea or Sneezing Repetitive coughing vomiting AccordingAccording toto thethe CDC,CDC, foodfood allergiesallergies resultresult inin moremore thanthan 300,000300,000 doctordoctor visitsvisits eacheach yearyear amongamong childrenchildren underunder thethe ageage ofof 18.18. Risk Factors Family history Children are at Having asthma or an of asthma or greater risk allergic condition such allergies than adults as hay fever or eczema WhatWhat CanCan YouYou BeBe AllergicAllergic To?To? Up to 4,145,700 people in the U.S. are PEANUTSPEANUTS allergic to peanuts. That’s more than the entire country population 25-40% of Panama! of people who are allergic to peanuts also have reactions to at least one tree nut. -

SAMPLE REPORT - STANDARD 150 We Hope That the Test Result & Report Will Give You Satisfactory Information and That It Enables You, to Make Informed Decisions

Independent Alternative Allergy Specialist Tripenhad, Tripenhad Road, Ferryside, SA17 5RS, Wales/UK 0345 094 3298 | [email protected] | www.allergylink.co.uk Combination Allergy & Intolerance Test Food Intolerance & Substance Sensitivity - Standard 150 - Ref No: AL#438 Name: SAMPLE Date: 15 January 2020 SSAAMMPPLLEE RREEPPOORRTT -- SSTTAANNDDAARRDD 115500 ©©CCooppyyrriigghhtt –– 22000044--22002200 AAlllleerrggyy LLiinnkk Updated: 15.01.2020 www.allergylink.co.uk ©2004-2020 Allergy Link SAMPLE REPORT - STANDARD 150 We hope that the Test Result & Report will give you satisfactory information and that it enables you, to make informed decisions. Content & Reference: Part 1: Test -Table 3 Low Stomach Acid / Enzyme deficiency 18 Part 2: About your Report 4-5 Other possible cause of digestive problems 19-20 About Allergies and Intolerances 5-7 Non-Food Items & Substances Part 3: Allergen’s and Reactions Explained 8 Pet Allergies, House dust mite & Pollen 20-21 Dairy / Lactose 8 Environmental toxins 21 Eggs & Chicken 9 Pesticides and Herbicides 21 Fish, Shellfish, Glucosamine 9 Fluoride (now classified as a neurotoxin) 22 Coffee, Caffeine & Cocoa / Corn 10 Formaldehyde, Chlorine 22 Gluten / Wheat 10 Toiletries / Preservatives MI / MCI 23 Yeast & Moulds 11 Perfume / Fragrance 23 Alcohol - beer, wine 11 Detergents & Fabric conditioners 23-24 Fruit , Citrus fruit 12 Aluminium, Nickel, Teflon, Latex 24 Fructose / FODMAPs | Cellery 12 Vegetables | Nightshades, Tomato 13 Part 4: Beneficial Supplementing of Vitamins & Minerals Soya , bean, products -

ALLERGY Fish/Seafood Allergy Means an Adverse Reaction to Proteins Found in Different Marine Species

PATIENT INFORMATION BROCHURE FISH AND SEAFOOD ALLERGY Fish/Seafood allergy means an adverse reaction to proteins found in different marine species. The immune system of sensitised/allergic individuals produces lgE antibodies, which causes release of histamine and harmful substances when the food is eaten. FISH Globally fish and seafood play an important role in human nutrition. The move to healthier eating habits and the substitution of meat with seafood in the diet has meant that more fish being ingested. In Southern Africa there are 2 000 different species of fish. SEAFOOD is the broad term used to describe 2 groups of marine animals: Crustaceans shrimp, rock lobster, prawns. Molluscs mussels, oysters, squid, calamari and octopus. If you are allergic to fish, you are not necessarily allergic to seafood. If you are allergic to crustaceans, you are not necessarily allergic to molluscs, and vice versa. WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF FISH/SEAFOOD ALLERGY? Allergy to seafood /fish could result in almost any allergy symptoms and sign, but some are more common than others. Common symptoms include skin rashes/swelling, nausea/vomiting and breathing difficulty. Respiratory symptoms may occur in sensitive subjects following inhalation of fumes from the cooked or braaied fish Most symptoms develop within 2 hours after eating, smelling or handling fish. Severe allergy can cause life-threatening anaphylaxis and needs to be treated with adrenaline. Fish/Seafood Allergy does not mean Iodine allergy! HOW COMMON IS SEAFOOD ALLERGY? True seafood allergy is more common in adults than children, but is more likely to persist in into adulthood, when present in a child. -

Early Exposure to Egg: Egg Allergy Prevention

Early exposure to egg: egg allergy prevention Intervention Introduction of egg to the diet of infants aged 4–6 months. Indication Infants, particularly those at higher risk of food allergy, with the aim of reducing the risk of developing egg allergy. (See Precautions.) [Hen’s egg allergy is the second most common food allergy Infants who started eating egg between 4 and 6 months of age show a 40% relative in infants and young children risk reduction of egg allergy compared with children who started egg later in life. (cow’s milk is the most common). In terms of absolute risk reduction, in a population where 5.4% of people have egg Most children outgrow egg allergy (ie reported UK prevalence rate), early egg introduction could prevent allergy by adolescence.] 24 cases of egg allergy per 1000 people. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommends introduction of solids (including egg and peanut) for all infants between 4 and 6 months of age. Precautions Infants with a personal history of atopy (particularly moderate-severe eczema) or with a family history of atopy are at high risk of developing allergic disease, including food allergies. These infants may benefit from evaluation by an allergist or a general practitioner trained in management of allergic diseases in this age group to diagnose food allergy and assist in early egg introduction if appropriate. Adverse effects There were no deaths in the studies (which included children at higher risk) and no significant differences in rates of serious adverse events in egg consumption groups and egg avoidance groups. -

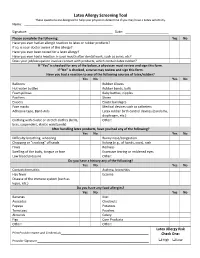

Latex Allergy Screening Tool These Questions Are Designed to Help Your Physician Determine If You May Have a Latex Sensitivity

Latex Allergy Screening Tool These questions are designed to help your physician determine if you may have a Latex sensitivity. Name: ____________________________________ __________ Signature: _________________________________ __________ Date: ______ _______________ Please complete the following: Yes No Have you ever had an allergic reaction to latex or rubber products? If so, is your doctor aware of this allergy? Have you ever been tested for a latex allergy? Have you ever had a reaction in your mouth after dental work, such as sores, etc? Does your job/occupation involve contact with products, which contain latex rubber? If “Yes” is checked for any of the below, a physician must review and sign this form. If “No” is checked, a nurse may review and sign this form. Have you had a reaction to any of the following sources of latex/rubber? Yes No Yes No Balloons Rubber Gloves Hot water bottles Rubber bands, balls Foam pillows Baby bottles, nipples Pacifiers Shoes Erasers Elastic bandages Face masks Medical devices such as catheters Adhesive tape, Band‐Aids Latex rubber birth control devices (condoms, diaphragm, etc.) Clothing with elastic or stretch clothes (belts, Other: bras, suspenders, elastic waistbands) After handling latex products, have you had any of the following? Yes No Yes No Difficulty breathing, wheezing Runny nose/congestion Chapping or “cracking” of hands Itching (e.g., of hands, eyes), rash Hives Redness Swelling of the body, tongue or face Excessive tearing or reddened eyes Low blood pressure Other: Do you have a history any of the following? Yes No Yes No Contact dermatitis Asthma, bronchitis Hay fever Eczema Disease of the immune system (such as lupus, etc.) Do you have any food allergies? Yes No Yes No Bananas Kiwi Avocados Chestnuts Papaya Potatoes Tomatoes Peaches Almonds Celery Figs Corn Products Other: Other: Latex Allergy Risk Print Provider Name and Credentials_________________________________________________ Check One: Provider Signature ______________________________________________________________ High Low . -

BSACI Egg Allergy (PDF)

Egg allergy What is egg allergy? How is egg allergy diagnosed? Egg allergy is caused by an allergic reaction to The diagnosis of egg allergy is based on the egg protein. This protein is found mostly in the history of previous reactions, and can be egg white but also on the yolk. It is common in confirmed by skin tests or blood tests. children under 5 years and usually first noticed in infancy when egg is introduced into the diet What is the treatment? for the first time. It is rare for egg allergy to The best current treatment is to avoid all food develop in adulthood. Those who develop egg containing egg for 1-2 years, allowing the allergy as adults may also be allergic to birds or allergy time to resolve. Egg may be found in a feathers which contain a protein which is similar wide range of foods, including: cakes, pastries, to that found in egg yolk. desserts, meat products, salad dressings, glazes, pasta, battered and bread crumbed What are the symptoms? foods, ice cream, chocolates and sweets. It Most reactions are mild. Commonly infants may also be referred to by unusual terms refuse the egg-containing food, develop especially on imported foods e.g. egg lecithin or redness and sometimes swelling around the albumen (=egg white). The proteins in eggs mouth soon after skin contact and then vomit from other birds are very similar to those in after eating. Stomach ache or diarrhoea may hens’ eggs and should be avoided too. This list also occur. Rarely, some children also develop is not exhaustive and because ingredients can a more severe reaction with cough, an asthma- change food labels must be read carefully type wheeze or even anaphylaxis. -

What You Need to Know About the New Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the U.S

Allergy guidelines insert_Layout 1 9/26/11 1:36 PM Page 1 What you need to know about the new guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the U.S. V OLUME 126, N O . 6 D ECEMBER 2010 • Tests for food-specific IgE are recom- Overview www.jacionline.org • The Guidelines, sponsored by the NIH Supplement to mended to assist in diagnosis, but should (NIAID), are based upon expert opinion THE JOURNAL OF not be relied upon as a sole means to di- Allergy ANDClinical and a comprehensive literature review. Immunology agnose food allergy. The medical history/ AAP had input on the document.1,2 exam are recommended to aid in diag- nosis. A medically monitored feeding Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management Definitions of Food Allergy in the United States: Report of the (food challenge) is considered the most NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel • Food allergy was defined as an adverse definitive test for food allergy. health effect arising from a specific im- • Food-specific IgE testing has numerous mune response. limitations; positive tests are not intrin- • Food allergies result in IgE-mediated sically diagnostic and reactions some- immediate reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis) OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF times occur with negative tests. These and several chronic diseases (e.g., ente- Supported by the Food Allergy Initiative issues are also reviewed in an AAP Clini - rocolitis syndromes, eosinophilic esopha - cal Report.3 Testing “food panels” with- gitis, etc), in which IgE may not play an important role. out considering history is often mis - leading. Tests selected to evaluate food allergy should be Epidemiology and Natural History based on the patient’s medical history and not comprise • Food allergy is more common in children than adults, large general panels of food allergens. -

Latex Allergy/Student Effective Date: 1/1/10

OCHSNER CLINICAL SCHOOL POLICY Policy #: OCS 400.14 Title: Latex Allergy/Student Effective Date: 1/1/10 PURPOSE The purpose of this policy is to establish guidelines for the identification, follow-up and work practice modification for all OCS medical students with latex sensitivities or allergies to ensure a consistent safe workplace. Students will be classified in the category of Health Care Worker (HCW) on the Ochsner campuses. Health Care Workers with demonstrated latex sensitivity will be provided with engineering controls, protective apparel and other interventions that will minimize opportunities for development of a true latex allergy. HCW’s with a diagnosed latex allergy will be provided a latex safe environment to the extent possible. DEFINITIONS: Latex refers to natural rubber latex and includes products made from dry natural rubber. Natural rubber latex is the product manufactured from a milky fluid derived mainly from the rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis. High-risk populations are groups known to have a higher risk for latex allergic reactions and include persons: • with occupational exposure to latex, • diagnosed with myelodysplasia, myeloma, congenital urologic abnormalities, or Spina bifida • with history of asthma, hay fever, contact dermatitis, or autoimmune disease (i.e. Lupus), • with food allergies such as bananas, avocados, potatoes, tomatoes, kiwi fruit, peaches, papaya, fruit or chestnuts and • who have exhibited contact dermatitis, itching or redness of the skin following the touching or wearing of latex products. Sensitization is the development of immunological memory in response to exposure to an antigen. Sensitivity is a clinical response that develops after sensitizations. Allergic reactions range from urticaria, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, angiodema, laryngeal edema, cardiovascular changes, GI upset, psychological distress, and bronchospasm, to severe life threatening anaphylaxis. -

Go Molecular! a Clinical Reference Guide to Molecular Allergy Part 2: the Allergen Components

Setting the standard in allergy diagnostics 2019 edition with the latest news in molecular allergology Go molecular! A clinical reference guide to molecular allergy Part 2: The allergen components Second edition | By Neal Bradshaw For more information on this topic allergyai.com Go molecular! Preface In the previous 2013 edition of Go the content in this new version of Go Molecular, I produced a straight forward Molecular has been aimed to provide clinical reference guide book to describe improved diagnostic explanations in common allergens and their constituent the form of tables, with concise clinical components. This guide is an update interpretation comments. Also new is a to the original but keeps the focus on section on aero-allergen components, understanding component test results, an introduction to micro-array, as well as well as what tests are actually as new information on diagnostic gaps commercial available (since this is an regarding certain food components. important practical aspect of molecular allergy!). If you need further supporting information relating to molecular allergy then I can Since 2013 the science of molecular recommend visiting our webpage: allergy has exploded with many new allergyai.com. studies both using single and multiplex allergen testing formats. There is a lot Neal Bradshaw of new clinical evidence to consider, Portfolio Manager - Allergy emerging allergens like alpha-gal and the Thermo Fisher Scientific availability of new ImmunoCAPTM Allergen Components. Beyond the new science, Disclaimer: The content of this book is intended as an aid to the physician to interpret allergen specific IgE antibody test results. It is not intended as medical advice on an individual level.