Meulemans 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructed Technosols: a Strategy Toward a Circular Economy

applied sciences Review Constructed Technosols: A Strategy toward a Circular Economy Debora Fabbri 1 , Romeo Pizzol 1, Paola Calza 1, Mery Malandrino 1 , Elisa Gaggero 1, Elio Padoan 2,* and Franco Ajmone-Marsan 2 1 Department of Chemistry, University of Turin, via P. Giuria 5, 10125 Turin, Italy; [email protected] (D.F.); [email protected] (R.P.); [email protected] (P.C.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (E.G.) 2 Department of Agricultural, Forestry and Food Sciences, University of Turin, 10095 Grugliasco, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Soil is a non-renewable natural resource. However, the current rates of soil usage and degra- dation have led to a loss of soil for agriculture, habitats, biodiversity, and to ecosystems problems. Urban and former industrial areas suffer particularly of these problems, and compensation measures to restore environmental quality include the renaturation of dismissed areas, de-sealing of surfaces, or the building of green infrastructures. In this framework, the development of methodologies for the creation of soils designed to mimic natural soil and suitable for vegetation growth, known as constructed soils or technosols, are here reviewed. The possible design choices and the starting materials have been described, using a circular economy approach, i.e., preferring non-contaminated wastes to non-renewable resources. Technosols appear to be a good solution to the problems of land degradation and urban green if using recycled wastes or by-products, as they can be an alternative to the remediation of contaminated sites and to importing fertile agricultural soil. -

The State of Soil in Europe

The State of Soil in Europe A contribution of the JRC to the European Environment Agency’s Environment State and Outlook Report— SOER 2010 Arwyn Jones, Panos Panagos, Sara Barcelo, Faycal Bouraoui, Claudio Bosco, Olivier Dewitte, Ciro Gardi, Markus Erhard, Javier Hervás, Roland Hiederer, Simon Jeffery, Anke Lükewille, Luca Marmo, Luca Montanarella, Claudia Olazábal, Jan-Erik Petersen, Vit Penizek, Thomas Strassburger, Gergely Tóth, Miet Van Den Eeckhaut, Marc Van Liedekerke, Frank Verheijen, Eva Viestova, Yusuf Yigini EUR 25186 EN - 2012 European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for Environment and Sustainability Contact information Arwyn Jones Address: TP 280, Via Enrico Fermi, 2749 ‐ 21027 ‐ Ispra (VA) – Italy E‐mail: [email protected] Tel.: +39 0332 789162 Fax: +39 0332 786394 http://ies.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ http://www.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/ JRC68418 EUR 25186 EN ISBN 978‐92‐79‐22805‐6 (print) ISBN 978‐92‐79‐22806‐3 (PDF) ISSN 1018‐5593 (print) ISSN 1831‐9424 (online) -

Tillage and Soil Ecology: Partners for Sustainable Agriculture

Soil & Tillage Research 111 (2010) 33–40 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Soil & Tillage Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/still Review Tillage and soil ecology: Partners for sustainable agriculture Jean Roger-Estrade a,b,*, Christel Anger b, Michel Bertrand b, Guy Richard c a AgroParisTech, UMR 211 INRA/AgroParisTech., Thiverval-Grignon, 78850, France b INRA, UMR 211 INRA/AgroParisTech. Thiverval-Grignon, 78850, France c INRA, UR 0272 Science du sol, Centre de recherche d’Orle´ans, Orle´ans, 45075, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Much of the biodiversity of agroecosystems lies in the soil. The functions performed by soil biota have Tillage major direct and indirect effects on crop growth and quality, soil and residue-borne pests, diseases Soil ecology incidence, the quality of nutrient cycling and water transfer, and, thus, on the sustainability of crop Agroecosystems management systems. Farmers use tillage, consciously or inadvertently, to manage soil biodiversity. Soil biota Given the importance of soil biota, one of the key challenges in tillage research is understanding and No tillage Plowing predicting the effects of tillage on soil ecology, not only for assessments of the impact of tillage on soil organisms and functions, but also for the design of tillage systems to make the best use of soil biodiversity, particularly for crop protection. In this paper, we first address the complexity of soil ecosystems, the descriptions of which vary between studies, in terms of the size of organisms, the structure of food webs and functions. We then examine the impact of tillage on various groups of soil biota, outlining, through examples, the crucial effects of tillage on population dynamics and species diversity. -

Soil As a Huge Laboratory for Microorganisms

Research Article Agri Res & Tech: Open Access J Volume 22 Issue 4 - September 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Mishra BB DOI: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2019.22.556205 Soil as a Huge Laboratory for Microorganisms Sachidanand B1, Mitra NG1, Vinod Kumar1, Richa Roy2 and Mishra BB3* 1Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, India 2Department of Biotechnology, TNB College, India 3Haramaya University, Ethiopia Submission: June 24, 2019; Published: September 17, 2019 *Corresponding author: Mishra BB, Haramaya University, Ethiopia Abstract Biodiversity consisting of living organisms both plants and animals, constitute an important component of soil. Soil organisms are important elements for preserved ecosystem biodiversity and services thus assess functional and structural biodiversity in arable soils is interest. One of the main threats to soil biodiversity occurred by soil environmental impacts and agricultural management. This review focuses on interactions relating how soil ecology (soil physical, chemical and biological properties) and soil management regime affect the microbial diversity in soil. We propose that the fact that in some situations the soil is the key factor determining soil microbial diversity is related to the complexity of the microbial interactions in soil, including interactions between microorganisms (MOs) and soil. A conceptual framework, based on the relative strengths of the shaping forces exerted by soil versus the ecological behavior of MOs, is proposed. Plant-bacterial interactions in the rhizosphere are the determinants of plant health and soil fertility. Symbiotic nitrogen (N2)-fixing bacteria include the cyanobacteria of the genera Rhizobium, Free-livingBradyrhizobium, soil bacteria Azorhizobium, play a vital Allorhizobium, role in plant Sinorhizobium growth, usually and referred Mesorhizobium. -

Sediment Diagenesis

Sediment Diagenesis http://eps.mcgill.ca/~courses/c542/ SSdiedimen t Diagenes is Diagenesis refers to the sum of all the processes that bring about changes (e.g ., composition and texture) in a sediment or sedimentary rock subsequent to deposition in water. The processes may be physical, chemical, and/or biological in nature and may occur at any time subsequent to the arrival of a particle at the sediment‐water interface. The range of physical and chemical conditions included in diagenesis is 0 to 200oC, 1 to 2000 bars and water salinities from fresh water to concentrated brines. In fact, the range of diagenetic environments is potentially large and diagenesis can occur in any depositional or post‐depositional setting in which a sediment or rock may be placed by sedimentary or tectonic processes. This includes deep burial processes but excldludes more extensive hig h temperature or pressure metamorphic processes. Early diagenesis refers to changes occurring during burial up to a few hundred meters where elevated temperatures are not encountered (< 140oC) and where uplift above sea level does not occur, so that pore spaces of the sediment are continually filled with water. EElarly Diagenesi s 1. Physical effects: compaction. 2. Biological/physical/chemical influence of burrowing organisms: bioturbation and bioirrigation. 3. Formation of new minerals and modification of pre‐existing minerals. 4. Complete or partial dissolution of minerals. 5. Post‐depositional mobilization and migration of elements. 6. BtilBacterial ddtidegradation of organic matter. Physical effects and compaction (resulting from burial and overburden in the sediment column, most significant in fine-grained sediments – shale) Porosity = φ = volume of pore water/volume of total sediment EElarly Diagenesi s 1. -

Dynamics of Carbon 14 in Soils: a Review C

Radioprotection, Suppl. 1, vol. 40 (2005) S465-S470 © EDP Sciences, 2005 DOI: 10.1051/radiopro:2005s1-068 Dynamics of Carbon 14 in soils: A review C. Tamponnet Institute of Radioprotection and Nuclear Safety, DEI/SECRE, CADARACHE, BP. 1, 13108 Saint-Paul-lez-Durance Cedex, France, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In terrestrial ecosystems, soil is the main interface between atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere and biosphere. Its interactions with carbon cycle are primordial. Information about carbon 14 dynamics in soils is quite dispersed and an up-to-date status is therefore presented in this paper. Carbon 14 dynamics in soils are governed by physical processes (soil structure, soil aggregation, soil erosion) chemical processes (sequestration by soil components either mineral or organic), and soil biological processes (soil microbes, soil fauna, soil biochemistry). The relative importance of such processes varied remarkably among the various biomes (tropical forest, temperate forest, boreal forest, tropical savannah, temperate pastures, deserts, tundra, marshlands, agro ecosystems) encountered in the terrestrial ecosphere. Moreover, application for a simplified modelling of carbon 14 dynamics in soils is proposed. 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of carbon 14 of anthropic origin in the environment has been quite early a matter of concern for the authorities [1]. When the behaviour of carbon 14 in the environment is to be modelled, it is an absolute necessity to understand the biogeochemical cycles of carbon. One can distinguish indeed, a global cycle of carbon from different local cycles. As far as the biosphere is concerned, pedosphere is considered as a primordial exchange zone. Pedosphere, which will be named from now on as soils, is mainly located at the interface between atmosphere and lithosphere. -

The Nature and Dynamics of Soil Organic Matter: Plant Inputs, Microbial Transformations, and Organic Matter Stabilization

Soil Biology & Biochemistry 98 (2016) 109e126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Soil Biology & Biochemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/soilbio Review paper The nature and dynamics of soil organic matter: Plant inputs, microbial transformations, and organic matter stabilization Eldor A. Paul Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory and Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1499, USA article info abstract Article history: This review covers historical perspectives, the role of plant inputs, and the nature and dynamics of soil Received 19 November 2015 organic matter (SOM), often known as humus. Information on turnover of organic matter components, Received in revised form the role of microbial products, and modeling of SOM, and tracer research should help us to anticipate 31 March 2016 what future research may answer today's challenges. Our globe's most important natural resource is best Accepted 1 April 2016 studied relative to its chemistry, dynamics, matrix interactions, and microbial transformations. Humus has similar, worldwide characteristics, but varies with abiotic controls, soil type, vegetation inputs and composition, and the soil biota. It contains carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, phenol-aromatics, protein- Keywords: Soil organic matter derived and cyclic nitrogenous compounds, and some still unknown compounds. Protection of trans- 13C formed plant residues and microbial products occurs through spatial inaccessibility-resource availability, 14C aggregation of mineral and organic constituents, and interactions with sesquioxides, cations, silts, and Plant residue decomposition clays. Tracers that became available in the mid-20th century made the study of SOM dynamics possible. Soil carbon dynamics Carbon dating identified resistant, often mineral-associated, materials to be thousands of years old, 13 Humus especially at depth in the profile. -

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE and the SOIL CARBON SOLUTION SEPTEMBER 2020

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE and the SOIL CARBON SOLUTION SEPTEMBER 2020 AUTHORED BY: Jeff Moyer, Andrew Smith, PhD, Yichao Rui, PhD, Jennifer Hayden, PhD REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE IS A WIN-WIN-WIN CLIMATE SOLUTION that is ready for widescale implementation now. WHAT ARE WE WAITING FOR? Table of Contents 3 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 A Potent Corrective 11 Regenerative Principles for Soil Health and Carbon Sequestration 13 Biodiversity Below Ground 17 Biodiversity Above Ground 25 Locking Carbon Underground 26 The Question of Yields 28 Taking Action ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 30 Soil Health for a Livable Future Many thanks to the Paloma Blanca Foundation and Tom and Terry Newmark, owners of Finca Luna Nueva Lodge and regenerative farm in 31 References Costa Rica, for providing funding for this paper. Tom is also the co-founder and chairman of The Carbon Underground. Thank you to Roland Bunch, Francesca Cotrufo, PhD, David Johnson, PhD, Chellie Pingree, and Richard Teague, PhD for providing interviews to help inform the paper. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The environmental impacts of agricultural practices This introduction is co-authored by representatives of two The way we manage agricultural land 140 billion new tons of CO2 contamination to the blanket of and translocation of carbon from terrestrial pools to formative organizations in the regenerative movement. matters. It matters to people, it matters to greenhouse gases already overheating our planet. There is atmospheric pools can be seen and felt across a broad This white paper reflects the Rodale Institute’s unique our society, and it matters to the climate. no quarreling with this simple but deadly math: the data are unassailable. -

Policy Brief Soil Sealing and Land Take

The RECARE project is funded by the European Commission FP7 Programme, ENV.2013.6.2-4 ‘Sustainable land care in Europe’. POLICY BRIEF SOIL SEALING AND LAND TAKE SUMMARY Urbanisation is an ongoing trend in Europe leading to land take and soil sealing at the expense of agricultural land and other open landscapes. Despite the extensive loss of productive soils and the valuable ecosystem services that soils provide, the awareness of the magnitude and negative implications of these processes remain relatively low. Systematic solutions are required to reduce the scale of land take and soil sealing. More specifically, an overall strategic aim and framework for sustainable soil management at EU and national level are needed, complemented by binding and quantitative land take targets and adequate financial and technical support at national scale. Municipal spatial planning is one of the most important instruments to foster sustainable city development and highlights the importance of cities to guide this process. This also includes testing and deploying new approaches such as joint regional planning, Open Space concepts or the application of zoning concepts to protect the most fertile and valuable soils from sealing. In this policy brief, we illustrate the scale of the problem and identify ready-made solutions and steps policy makers and practitioners can take across different levels, from city planning to national and European level. INTRODUCTION B Europe loses about 1.007 km² of soil due to land take M r annually (EEA 2017), which is approximately a loss f the size of the city of Berlin. Land take especially affects metropolitan areas (peri-urban areas) usually e characterized by land with high soil quality and some of the most productive agricultural soils. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

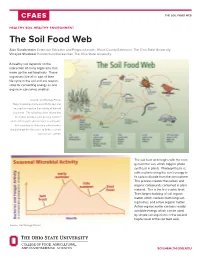

The Soil Food Web

THE SOIL FOOD WEB HEALTHY SOIL HEALTHY ENVIRONMENT The Soil Food Web Alan Sundermeier Extension Educator and Program Leader, Wood County Extension, The Ohio State University. Vinayak Shedekar Postdoctural Researcher, The Ohio State University. A healthy soil depends on the interaction of many organisms that make up the soil food web. These organisms live all or part of their life cycle in the soil and are respon- sible for converting energy as one organism consumes another. Source: Soil Biology Primer The phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) test can be used to measure the activity of the soil food web. The following chart shows that mi-crobial activity peaks in early summer when soil is warm and moisture is adequate. Soil sampling for detecting soil microbes should follow this timetable to better capture soil microbe activity. The soil food web begins with the ener- gy from the sun, which triggers photo- synthesis in plants. Photosynthesis re- sults in plants using the sun’s energy to fix carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This process creates the carbon and organic compounds contained in plant material. This is the first trophic level. Then begins building of soil organic matter, which contains both long-last- ing humus, and active organic matter. Active organic matter contains readily available energy, which can be used by simple soil organisms in the second trophic level of the soil food web. Source: Soil Biology Primer SOILHEALTH.OSU.EDU THE SOIL FOOD WEB - PAGE 2 The second trophic level contains simple soil organisms, which Agriculture can enhance the soil food web to create more decompose plant material. -

Land Consumption and Land Take: Enhancing Conceptual Clarity for Evaluating Spatial Governance in the EU Context

sustainability Article Land Consumption and Land Take: Enhancing Conceptual Clarity for Evaluating Spatial Governance in the EU Context Elisabeth Marquard 1,* , Stephan Bartke 1 , Judith Gifreu i Font 2 , Alois Humer 3 , Arend Jonkman 4 , Evelin Jürgenson 5, Naja Marot 6, Lien Poelmans 7 , Blaž Repe 8 , Robert Rybski 9, Christoph Schröter-Schlaack 1, Jaroslava Sobocká 10, Michael Tophøj Sørensen 11 , Eliška Vejchodská 12,13 , Athena Yiannakou 14 and Jana Bovet 15 1 Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research—UFZ, Department of Economics, Permoserstraße 15, 04318 Leipzig, Germany; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (C.S.-S.) 2 Faculty of Law, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), 08193 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Geography and Regional Research, University of Vienna, Universitaetsstrasse 7/5, 1010 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 4 Department of Management in the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, Julianalaan 134, 2628BL Delft, The Netherlands; [email protected] 5 Chair of Geomatics, Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Kreutzwaldi 5, 51014 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] 6 Biotechnical Faculty, Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Ljubljana, Jamnikarjeva ulica 101, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] 7 VITO—Vlaamse Instelling voor Technologisch Onderzoek, Unit Ruimtelijke Milieuaspecten, Boeretang 200, 2400 Mol, Belgium; [email protected]