Addressing Modern Slavery in Tamil Nadu Textile Industry - Feasibility Study Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexure-PFR File

FORM-1, PREFEASIBILITY REPORT, MODIFIED MINING PLAN FOR ROUGH STONE QUARRY, S.F.NO: 211, ALUR VILLAGE, HOSUR TALUK, KRISHNAGIRI DISTRICT AND TAMILNADU STATE OF TVL. CHENNAI MINES. PREFEASIBILITY REPORT CHAPTER -1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT / BACKGROUND INFORMATION: TVL. CHENNAI MINES, has already obtained quarry in Rough Stone deposit over an extent of 3.46.5HA in S.F.No. 211, in ALUR Village, HOSUR Taluk, KRISHNAGIRI District and TAMILNADU State for FIVE years. The District Collector, KRISHNAGIRI vide their letter no. 276 / 2013 / Mines-2 dated 07.12.2013 have conveyed its decision to grant lease over an extent of 3.46.5HA in S.F.No. 211, in ALUR Village, HOSUR Taluk, KRISHNAGIRI District and TAMILNADU State and Requested TVL. CHENNAI MINES to submit the Approved Modified mining plan through the Department of Geology and Mining, KRISHNAGIRI and also obtain Environmental Clearance from DEIAA. Department of Geology and Mining, KRISHNAGIRI vide their Rc. No. 1326 / 2018 / Mines dated 11.10.2018. have approved the Modified Mining Plan over an extent of 3.46.5HA in S.F.No. 211, in ALUR Village, HOSUR Taluk, KRISHNAGIRI District and TAMILNADU State. (Copy of Modified Mining plan approval letter enclosed). TVL. CHENNAI MINES, Six Months and One Year Proposed to quarry Rough Stone for 419006m³ and 23278m³ Per Month from this lease applied area by open cast semi- mechanized mining technique. This feasibility report is prepared towards obtaining the Environmental Clearance. As per MOEF O.M. No. L - 11011/47/2011 –A.II (M) dated 18th May, 2012, leases of minor minerals also require environmental clearance. -

VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT Minerals and Mining Irrigation Practices

VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT Virudhunagar district has no access to sea as it is covered by land on all the sides. It is surrounded by Madurai on the north, by Sivaganga on the north-east, by Ramanathapuram on the east and by the districts of Tirunelveli and Tuticorin on the south. Virudhunagar District occupies an area of 4288 km² and has a population of 1,751,548 (as of 2001). The Head-Quarters of the district Virudhunagar is located at the latitude of 9N36 and 77E58 longitude. Contrary to the popular saying that 'Virudhunagar produces nothing, but controls everything', Virudhunagar does produce a variety of things ranging from edible oil to plastic-wares. Sivakasi known as 'Little Japan' for its bustling activities in the cracker industry is located in this district. Virudhunagar was a part of Tirunelveli district before 1910, after which it became a part of Ramanathapuram district. After being grafted out as a separate district during 1985, today it has eight taluks under its wings namely Aruppukkottai, Kariapatti, Rajapalayam, Sattur, Sivakasi, Srivilliputur, Tiruchuli and Virudhunagar. The fertility of the land is low in Virudhunagar district, so crops like cotton, pulses, oilseeds and millets are mainly grown in the district. It is rich in minerals like limestone, sand, clay, gypsum and granite. Tourists from various places come to visit Bhuminathaswamy Temple, Ramana Maharishi Ashram, Kamaraj's House, Andal, Vadabadrasayi koi, Shenbagathope Grizelled Squirrel Sanctuary, Pallimadam, Arul Migu Thirumeni Nadha Swamy Temple, Aruppukkottai Town, Tiruthangal, Vembakottai, Pilavakkal Dam, Ayyanar falls, Mariamman Koil situated in the district of Virudhunagar. Minerals and Mining The District consists of red loam, red clay loam, red sand, black clay and black loam in large areas with extents of black and sand cotton soil found in Sattur and Aruppukottai taluks. -

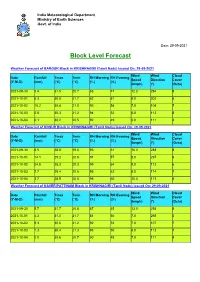

Block Level Forecast

India Meteorological Department Ministry of Earth Sciences Govt. of India Date: 29-09-2021 Block Level Forecast Weather Forecast of BARGUR Block in KRISHNAGIRI (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 29-09-2021 Wind Wind Cloud Date Rainfall Tmax Tmin RH Morning RH Evening Speed Direction Cover (Y-M-D) (mm) (°C) (°C) (%) (%) (kmph) (°) (Octa) 2021-09-30 5.4 31.5 20.7 88 47 12.0 294 8 2021-10-01 5.3 30.8 21.7 82 51 6.0 302 5 2021-10-02 10.2 30.4 21.0 93 54 7.0 108 7 2021-10-03 0.8 30.3 21.2 94 52 6.0 113 8 2021-10-04 0.1 30.2 20.5 92 49 6.0 111 4 Weather Forecast of HOSUR Block in KRISHNAGIRI (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 29-09-2021 Wind Wind Cloud Date Rainfall Tmax Tmin RH Morning RH Evening Speed Direction Cover (Y-M-D) (mm) (°C) (°C) (%) (%) (kmph) (°) (Octa) 2021-09-30 8.5 28.8 19.6 93 61 16.0 288 8 2021-10-01 14.1 29.2 20.6 91 57 8.0 297 6 2021-10-02 24.8 28.3 20.3 95 64 9.0 113 6 2021-10-03 2.7 28.4 20.6 95 62 8.0 114 7 2021-10-04 3.7 28.9 20.0 95 60 10.0 113 4 Weather Forecast of KAVERIPATTINAM Block in KRISHNAGIRI (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 29-09-2021 Wind Wind Cloud Date Rainfall Tmax Tmin RH Morning RH Evening Speed Direction Cover (Y-M-D) (mm) (°C) (°C) (%) (%) (kmph) (°) (Octa) 2021-09-30 5.7 31.7 20.8 87 45 13.0 293 8 2021-10-01 4.3 31.0 21.7 81 50 7.0 298 5 2021-10-02 9.3 30.6 21.2 92 53 7.0 107 7 2021-10-03 1.3 30.4 21.3 93 50 6.0 113 7 2021-10-04 0.0 30.6 20.7 90 48 7.0 111 4 India Meteorological Department Ministry of Earth Sciences Govt. -

Sumangali Scheme and Bonded Labour in India

Fair Wear Foundation – September 2010 Sumangali scheme and bonded labour in India In early September, Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant published a series of articles on bonded labour in Coimbatore, India. Young girls were reported to be trapped in hostels of textile mills working under hazardous conditions. Fair Wear Foundation was asked to give an insight into the issue. According to a report published in 2007, the government of India identified and released 280,000 bonded labourers. 46% of them were from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka1. During FWF‟s consultation of local stakeholders in July 2010, However, Social Awareness and Voluntary Education (SAVE), a local NGO in Tiruppur told FWF that the Sumangali scheme is still prevalent. The Sumangali scheme, which is a form of forced labour in India, is said to have started in 1989. The word “Sumangali” in Tamil means an unmarried girl becoming a respectable woman by entering into marriage. Thus, the scheme is also known as “marriage assistance system”. In an ordinary Hindu arranged marriage, the bride‟s parents must provide the groom‟s family a substantial dowry, and should bear the expenses of the wedding. If she doesn‟t meet the expectation of the groom‟s family, the bride is prone to extreme hardships after marriage. Under the Sumangali scheme, girls‟ parents, usually poor and from the lower castes, are persuaded by brokers to sign up their daughter(s). The scheme promises a bulk of money after completion of a three-year contract working in the factory. It – ostensibly – meets the need of poor families and provides stable workforce to factories in Coimbatore. -

District Survey Report for Clay (Others)

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR CLAY (OTHERS) VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT TAMILNADU STATE (Prepared as per Gazette Notification S.O.3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climatic Change) 1 PREFACE In Compliance to the Notification Issued by the Ministry of Environment, ForestandClimatechangeDated15.01.2016,and its subsequent amended notification S.O.3611(E) dated 25.07.2018, the District Survey Report shall be prepared for each minor mineral in the district separately by the District Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA)with assistance of irrigation department, Drainage department, Forest department, Mining department and Revenue department in the district. Accordingly District Survey Report for the mineral Clay (Others) has been prepared as per the procedure prescribed in the notification S.O.3611(E) dated 25.07.2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Every effort have been made to cover mining locations , areas & overview of Mining activity in the district with all its relevant features pertaining to geology & mineral wealth in replenishable and non- replenishable areas. This report will be a model and guiding document which is a compendium of available mineral resources, geographical setup, environmental and ecological setup of the District and is based on data of various departments, published reports and websites. 2 1.INTRODUCTION Virudhunagar District came into existence by the bifurcation of Ramanathapuram District vide State Government Notification, G.O. Ms. 347 dated 8.3.1985. It is bounded on North by Madurai and Sivagangai District, South by Tirunelveli and Tuticorin District, East by Ramanathapuram District, West by Kerala State and NorthWest by Theni District. -

INDIA the Economic Scenario

` ` 6/2020 INDIA Contact: Rajesh Nath, Managing Director Please Note: Jamly John, General Manager Telephone: +91 33 40602364 1 trillion = 100,000 crores or Fax: +91 33 23217073 1,000 billions 1 billion = 100 crores or 10,000 lakhs E-mail: [email protected] 1 crore = 100 lakhs 1 million= 10 lakhs The Economic Scenario 1 Euro = Rs.82 Economic Growth As per the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), India’s economy could prove the most resilient in South Asia and its large market will continue to attract market-seeking investments to the country even as it expects a dramatic fall in global foreign direct investment (FDI). However, inflows may shrink sharply. India jumped to ninth spot in 2019 on the list of global top FDI recipients from the twelfth spot in 2018. Due to the Covid-19 crisis, global FDI flows are forecast to nosedive by upto 40% in 2020, from their 2019 value of € 1.40 ($1.54) trillion, bringing FDI below € 0.91 ($1) trillion for the first time since 2005. FDI is projected to decrease by a further 5-10% in 2021 and a recovery is likely in 2022 amid a highly uncertain outlook. A rebound in 2022, with FDI reverting to the pre-pandemic underlying trend, is possible, but only at the upper bound of expectations. The outlook looks highly uncertain. FDI inflows into India rose 13% on year in FY20 to a record € 45 ($49.97) billion compared to € 40 ($44.36) billion in 2018-19. In 2019, FDI flows to the region declined by 5%, to € 431 ($474) billion, despite gains in South East Asia, China and India. -

The Strange and Persisting Case of Sumangali (Or, the Highway to Modern Slavery)

The strange and persisting case of Sumangali (or, the highway to modern slavery) Historical context Something extraordinary has been going on in the textile sector in Tamil Nadu, specifically in the spinning mills in the Tirupur area. Extraordinary because this sector did practically not exist before the 1970’s, and its emergence has been the result of a remarkable caste transformation. In this process of expansion, the local community of upper caste peasant farmers, Gounders, was turned into a new class of industrial capitalists. In villages surrounding Tirupur, Gounder landowners began to set up powerloom units with anything from 4 to 50 looms. Initially they operated their looms with family labour, later recruiting Gounder wage labourers, and then local Dalits. As looms continued to be established, Gounders began employing migrant workers from neighbouring districts, for whom they provide accommodation. 1 Extraordinary too because employment in the textile ‘godowns’ offered Dalits and other excluded groups, such as Christians, ways to escape from the usual prospect to work in agriculture. Wages are generally higher in the mills, and there is also considerable scope for upward mobility within the garment industry. Entrepreneurial tailors may manage to become labour contractors or supervisors as their career advances. In contrast, agricultural labourers have no such opportunities for progression, and are stuck on much lower wages. While incomes are higher in Tirupur, working hours are also longer than those in agriculture. But despite the longer hours, people in villages perceived the working conditions in Tirupur to be attractive and factories as desirable places to work. 2 Carswell and De Neve write that “Workers routinely comment on the contrasts with agricultural work: they can work out of the sun and under a fan, much of the work can be done sitting down, and men can dress in shirt and trousers and women in a neat salwar kameez or saree … and those who work in Tirupur are frequently described as ‘neat’ and ‘clean’. -

Evaluation of Sumangali Eradication of Extremely Exploitative Working Conditions in Southern India’S Textile Industry

Evaluation of Sumangali Eradication of extremely exploitative working conditions in southern India’s textile industry June 2019 Kaarak Enterprise Development Services Private Limited Contents Abbreviations 2 Acknowledgement 4 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 15 Context analysis 15 About the project 18 About the evaluation 19 Evaluation Findings 22 Relevance and validity of design 22 Effectiveness and results 25 Efficiency 36 Sustainability 40 Lessons and Recommendations 42 Lessons learned 42 Recommendations 43 Annexure 46 Annexure 1: Evaluation questions 46 Annexure 2: Theory of Change (Results Framework) 48 Annexure 3: Indicator matrix 49 Annexure 4: Analysis of psychosocial care methodology 51 Annexure 5: Case studies 54 Annexure 6: A note on project implementing partners 58 Annexure 7: List of documents reviewed 60 Annexure 8: Rating system 63 Annexure 9: Implementation status of activities and outputs 65 EVALUATION OF SUMANGALI: ERADICATION OF EXTREMELY EXPLOITATIVE WORKING CONDITIONS IN SOUTHERN INDIA’S TEXTILE INDUSTRY Abbreviations AIADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam ASK Association for Stimulating Know how BMZ German Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development BSI British Standards Institution CARE-T Community Awareness Research Education Trust CSO Civil Society Organization CYC Child and Youth Centre DAC Development Assistance Committee DeGEval German Evaluation Society ETI Ethical Trade Initiative FGD Focus Group Discussion FWF Fair Wear Foundation GTA Partnership for Sustainable Textiles or German Textile Alliance -

Archaeology of Krishnagiri District, Tamil Nadu

Volume 4, Issue 1, January – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Archaeology of Krishnagiri District, Tamil Nadu S. Paranthaman Ph.D Research Scholar Dept. of Ancient History and Archaeology University of Madras Abstract:- Kirshnagiri district has glories historic past Guttur, which was later on excavated him in 1976 (IAR1977- revealed from epigraphical records from the temples and 78:50, IAR 1982-83:71-72). After, K.V. Raman, K. Rajan from the Herostone inscriptions. This district has many explored this region and have brought to light a Paleolithic forts built during Vijayanagara-nayakav period. But site at Varatanapalli and have located many archaeological there is a lacuna in understanding the early history of site with Megalithic, Early Historical material remains and Krishnagiri district. This article pertains to the recent few rockshelters with rock art (Rajan 1997:111-195). After finding from the district of Krishnagiri, by means of K. Rajan, freelancers have reported many site with rock art reconnaissance survey. The intensive exploration work in from this area. this region has brought to light a large corpse of information of the inhabitants from early phase of III. PRESENT EXPLORATION Krishnagiri district especially from Paleolithic to Iron Age period. Present exploration in this district have brought light large corpus of information on the occurrence of This article pertains to the recent finding from the archeological site from Krishnagiri district. Systematic district of Krishnagiri in Tamil Nadu state, by means of exploration by the present author of this article have brought reconnaissance survey. The intensive exploration work in to light new archaeological sites (refer Appendix 1 for list of this region has brought to light a large corpse of sites) (Fig-2). -

District Survey Report of Krishnagiri District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT KRISHNAGIRI DISTRICT Aadhi Boomi Mining and Enviro Tech (P) Ltd., 3/216, K.S.V.Nagar, Narasothipatti, Salem-636 004. Phone (0427) 2444297, Cell: 09842729655 [email protected], [email protected] DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF KRISHNAGIRI DISTRICT INDRODUCTION Krishnagiri is a municipal town and administrative headquarters of Krishnagiri District.It is located 90 Km from Bangalore and 45 Km from Hosur and Dharmapuri.The krishnagiri district has a prehistoric importance.Archeological sources confirm the presence of habitats of man kind during Paleolithic, Neolithic and Mesolithic Ages.Krishnagiri District was bifurcated from the erstwhile Dharmapuri District and Krishnagiri District came into existence from 9th February 2004, consisting of Hosur and Krishnagiri Divisions. After the bifurcation of Krishnagiri District from Dharmapuri, the present Krishnagiri is located approximately between 11°12’N and 12°49’N of the north latitude and between 77°27’E and 78°38’E of east longitude. The total geographical area of the district is 5143 Sq. Km. This District is elevated from 300 m to 1400 m above the mean sea level. The total Geographical extent of Krishnagiri District is 5,14,326 hectares. It had 2, 02,409 hectares of forest land which constituted nearly 40 percent of the total geographical area of the district. Krishnagiri District has two Municipalities, 10 Panchayat Unions, seven Town Panchayats, 352 Village Panchayats and 636 Revenue Villages. Shoolagiri, Thally and Veppanapalli blocks have vast stretches of forest area with large tribal population. 2. ADMINISTRATION A district collector heads the district administration. Krishnagiri district is divided into two divisions and five taluks for the purpose of revenue administration. -

Captured by Cotton Exploited Dalit Girls Produce Garments in India for European and US Markets

Captured by Cotton Exploited Dalit girls produce garments in India for European and US markets May 2011 SOMO - Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations ICN - India Committee of the Netherlands SO M O Captured by Cotton Exploited Dalit girls produce garments in India for European and US markets May 2011 SOMO - Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations ICN - India Committee of the Netherlands Table of content Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Tamil Nadu cotton-based garment industry 7 Chapter 2 The Sumangali Scheme in its worst form 9 Chapter 3 Vertically integrated garment production – four cases 19 Chapter 4 Efforts to phase out the Sumangali Scheme 25 Chapter 5 Conclusion and Recommendations 30 Annex 1 Eliminating Sumangali and Camp Coolie Abuses in the Tamil Nadu Garment Industry. Joint Statement of intent 32 Annex 2 Response to SOMO / ICN / CASS report by ASOS, Bestseller, C&A, Grupo Cortefiel, H&M, Mothercare, Next, Primark and Tesco – May 2011 35 Endnotes 36 Captured by Cotton Introduction In India, in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, girls and young women are recruited and employed on a large scale to work in the garment industry. The promise: a decent wage, comfortable accommodation, and, the biggest lure: a considerable sum of money upon completion of their three-year contract. This lump sum may be used to pay for a dowry. Although the payment of a dowry has been prohibited in India since 1961, it is still a general practice in rural India for which families often incur high debts. The recruitment and employment scheme – the Sumangali Scheme – that is the subject of this report is closely linked to the payment of a dowry. -

Copy of Sumangali Scheme – Report

1 PROGRAMME OBJECTIVES: Analyse the pro and cons of the Sumangali Scheme Discuss the issues and problems of the scheme Identify the status of the schemes and its current impact in Virudhunagar district Create solidarity among the civil society organizations, unions, social volunteers and victims stand against the exploiting schemes. Promote vigilance committees in appropriate blocks where the impact of the scheme is crucial. Draft the demands to government against the issues of the scheme Consultation on the Issue of Sumangali Scheme for the Civil Society Organisations – Virudhunagar Dist 03/07/2013 2 Consultation on the Issue of Sumangali Scheme for the Civil Society Organisations Inauguration ‘Consultation on the issue of Sumangali Scheme for the Civil Society organisations’ was held on 03.07.2013 by 10.00 a.m at Muthusamy Marriage hall, Srivilliputtur town of Virudhunagar District. CSED, Avinasi, NEEDS, Srivilliputtur and Civil Society Organizations (CSO) working in Virudhunagar District had jointly organized the programme. About 61 representatives from various NGOs working in Virudhunagar district, lawyers, Representatives of Women Rights Federation Movement, Textile mill workers, Political Parties and representative of All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) were actively participated and shareed their views and experiences. Welcome Address: Mr. RajaGopal, President, NEEDS gave welcome address and encourged all the participants to actively involve in the session by sharing their views and local information. Consultation Introduction: Mr. Nambi, Director, CSED gave special address on objectives of the programme and various issues and problems of women labourers working under ‘Sumangali Scheme’ in Tiruppur, Kovai and Erode districts who are hired from various districts of Tamil Nadu.