Slavery, Free Blacks and Citizenship Henry L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How Does the United States Immigration System Work?

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How does the United States immigration system work? Multiple agencies are responsible for the execution of immigration laws. o The Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) was abolished in 2003. o Department of Homeland Security . USCIS . CBP . ICE . Attorney General’s role o Department of Justice . EOIR . Attorney General’s role o Department of State . Consulates . Secretary of State’s role o Department of Labor . Employment‐related immigration Our laws, while historically pro‐immigration, have become increasingly restrictive and punitive with respect to noncitizens – even those with lawful status. ‐ Pro‐immigration history of our country o First 100 Years: 1776‐1875 ‐ Open door policy. o Act to Encourage Immigration of 1864 ‐ Made employment contracts binding in an effort to recruit foreign labor to work in factories during the Civil War. As some states sought to restrict immigration, the Supreme Court declared state laws regulating immigration unconstitutional. ‐ Some early immigration restrictions included: o Act of March 3, 1875: excluded convicts and prostitutes o Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: excluded persons from China (repealed in 1943) o Immigration Act of 1891: Established the Bureau of Immigration. Provided for medical and general inspection, and excluded people based on contagious diseases, crimes involving moral turpitude and status as a pauper or polygamist ‐ More big changes to the laws in the early to mid 20th century: o 1903 Amendments: excluded epileptics, insane persons, professional beggars, and anarchists. o Immigration Act of 1907: excluded feeble minded persons, unaccompanied children, people with TB, mental or physical defect that might affect their ability to earn a living. -

Primer on Criminal-Immigration and Enforcement Provisions of USCA

U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021: A Brief Primer on the Criminal-Immigration and Enforcement Provisions1 I. Introduction This primer covers the key criminal-immigration and enforcement provisions of the USCA. The US Citizenship Act of 2021 (USCA, also referred to as the “Biden bill”) is an immigration bill introduced in the House on February 18, 20212 that would create a pathway to citizenship for undocumented people living in the United States who entered on or before January 1, 2021. TPS holders, farmworkers, and people who have DACA or who were eligible for status under the Dream Act would be eligible to become lawful permanent residents immediately. Other undocumented people could apply for a new form of lawful status called “Lawful Provisional Immigrant” (LPI) status. After five years as LPIs, they could then apply to become lawful permanent residents. The bill would also recapture unused visas dating from 1992; make spouses, children, and parents of lawful permanent residents “immediate relatives” (who are immediately eligible for visas and who do not count toward the cap); make anyone waiting more than 10 years immediately eligible for a visa; and increase the per-country limit from 7% to 20% to decrease backlogs. The USCA imposes new criminal bars to eligibility for the legalization program, on top of the already existing inadmissibility bars in current immigration law. It also encourages the construction of a “smart wall” and adds an additional ground for prosecution and penalties under 8 U.S.C. § 1324. The USCA also includes some positive criminal-immigration reforms, including redefining the term “conviction” for immigration purposes, increasing the number of petty offense exceptions 1 Publication of the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild (NIPNLG), 2020. -

Naturalized U.S. Citizens: Proving Your Child's Citizenship

Fact Sheet Naturalized U.S. Citizens: Proving Your Child’s Citizenship If you got your U.S. citizenship and you are a parent, your non-citizen children also become citizens in some cases. This is called “derived” citizenship. BUT you still need to get documents like a certificate of citizenship or a passport, to PROVE that your child is a citizen. This fact sheet will tell you the ways to get these documents. This fact sheet does not give information about the process of getting documents to prove citizenship for children born in the U.S., children born outside the U.S. to U.S. citizen parents, or children adopted by U.S. citizens. This fact sheet talks about forms found on the internet. If you don’t have a computer, you can use one at any public library. You can also call the agency mentioned and ask them to send you the form. When a parent becomes a citizen, are the children automatically citizens? The child may be a U.S. citizen if ALL these things are, or were, true at the same time: 1. The child is under 18 years old. 2. The child is a legal permanent resident of the U.S. (has a green card) 3. At least one of the parents is a U.S. citizen by birth or naturalization. If that parent is the father but not married to the other parent, talk to an immigration lawyer. 4. The citizen parent is the biological parent of the child or has legally adopted the child. -

Same-Sex Marriage, Second-Class Citizenship, and Law's Social Meanings Michael C

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 10-1-2011 Same-Sex Marriage, Second-Class Citizenship, and Law's Social Meanings Michael C. Dorf Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Dorf, Michael C., "Same-Sex Marriage, Second-Class Citizenship, and Law's Social Meanings" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 443. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/443 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES SAME-SEX MARRIAGE, SECOND-CLASS CITIZENSHIP, AND LAW'S SOCIAL MEANINGS Michael C. Dorf and symbols that carry the G socialOVERNMENT meaning ofacts, second-class statements, citizenship may, as a conse- quence of that fact, violate the Establishment Clause or the constitu- tional requirement of equal protection. Yet social meaning is often contested. Do laws permitting same-sex couples to form civil unions but not to enter into marriage convey the social meaning that gays and lesbians are second-class citizens? Do official displays of the Confederate battle flag unconstitutionallyconvey supportfor slavery and white supremacy? When public schools teach evolution but not creationism, do they show disrespect for creationists? Different au- diences reach different conclusions about the meaning of these and other contested acts, statements, and symbols. -

Children's Right to a Nationality

OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE Children’s right to a nationality Statelessness affects more than 12 million people around the world, among whom the most vulnerable are children. The Open Society Justice Initiative estimates that as many as 5 million may be minors. The consequences of lack of nationality are numerous and severe. Many stateless children grow up in extreme poverty and are denied basic rights and services such as access to education and health care. Stateless children‟s lack of identity documentation limits their freedom of movement. They are subject to arbitrary deportations and prolonged detentions, are vulnerable to social exclusion, trafficking and exploitation—including child labor. Despite its importance, children‟s right to a nationality rarely gets the urgent attention it needs. Children’s right to nationality The right to a nationality is protected under At the very least, the right to acquire a nationality under international law. The Universal Declaration of Human the CRC should be understood to mean that children Rights provides a general right to nationality under have a right to nationality in their country of birth if article 15. The international human rights treaties— they do not acquire another nationality from birth—in including the Convention on the Rights of the Child other words, if they would otherwise be stateless. In (CRC) and the International Covenant on Civil and fact, this particular principle is recognized in regional Political Rights (ICCPR)—as well as the Convention on systems as well as in the Convention on the Reduction the Reduction of Statelessness, provide particular norms of Statelessness. -

Free Movement of Persons

FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS Freedom of movement and residence for persons in the EU is the cornerstone of Union citizenship, established by the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992. The gradual phasing-out of internal borders under the Schengen agreements was followed by the adoption of Directive 2004/38/EC on the right of EU citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the EU. Notwithstanding the importance of this right, substantial implementation obstacles persist. LEGAL BASIS Article 3(2) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU); Article 21 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU); Titles IV and V of the TFEU; Article 45 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. OBJECTIVES The concept of the free movement of persons has changed in meaning since its inception. The first provisions on the subject, in the 1957 Treaty establishing the European Economic Community , covered the free movement of workers and freedom of establishment, and thus individuals as employees or service providers. The Treaty of Maastricht introduced the notion of EU citizenship to be enjoyed automatically by every national of a Member State. It is this EU citizenship that underpins the right of persons to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States. The Lisbon Treaty confirmed this right, which is also included in the general provisions on the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. ACHIEVEMENTS A. The Schengen area The key milestone in establishing an internal market with free movement of persons was the conclusion of the two Schengen agreements, i.e. -

Am I a German Citizen? If You Are US Citizen of German Origin and Would

Am I a German citizen? If you are US citizen of German origin and would like to find out if you are eligible to apply for a German passport, there are some basic principles of German citizenship law that you should familiarize yourself with first: German citizenship is mainly acquired and passed on through descent from a German parent . The parent has to be German citizen at the time of the birth of the child. Children who are born to former German citizens do not acquire German citizenship. In addition, for children born before January 1st, 1975 to parents who were married to each other at the time of the birth, it was mandatory that the father was a German citizen in order for the child to acquire German citizenship. Persons who were born in Germany before the year 2000 to non-German parents did not obtain German citizenship at the time of their birth and are not eligible for a German passport. Only children born in or after the year 2000 to long-term residents of Germany could or can under certain circumstances receive German citizenship. The German rules on citizenship are based on the principle of avoiding dual citizenship . This means that a German citizen who voluntarily applies for and accepts a foreign nationality on principle loses the German nationality automatically. This rule does not apply to Germans who receive the other citizenship by law or who applied for and received a citizenship of a member state of the European Union or Switzerland after August of 2007. Am I entitled to a German passport? German passports are only issued to German citizens. -

The Campaign to End Statelessness and Perfect Citizenship in Lebanon

The Campaign to End Statelessness and Perfect Citizenship in Lebanon Researched and Written by: Boston University International Human Rights Clinic Law Students Claudia Bennett and Kristina Fried Supervised and edited by Clinical Professor Susan M. Akram This Report was made possible in part with a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, through the 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction _____________________________________________________________ 3 II. Problem Statement ________________________________________________________ 3 III. Methodology _____________________________________________________________ 4 IV. Background and Context of Citizenship and Statelessness in Lebanon ______________ 5 V. Legal Background _______________________________________________________ 10 A. Domestic Law _______________________________________________________________ 10 B. International Law ____________________________________________________________ 12 C. Regional Law _______________________________________________________________ 15 VI. Gaps in Lebanon’s Legal Framework________________________________________ 16 A. Obligations under International Law _____________________________________________ 17 B. Obligations under Domestic Law ________________________________________________ 19 1. Civil Registration ___________________________________________________________________ 19 2. Nationality Law ____________________________________________________________________ 24 3. Refugee and Stateless Persons Registration ______________________________________________ -

Nationality Law in Germany and the United States

Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series No. 00.5 The Legal Construction of Membership: Nationality ∗ Law in Germany and the United States by Mathias Bös Institute of Sociology University of Heidelberg D-69117 Heidelberg Abstract The argument of this paper is that several empirical puzzles in the citizenship literature are rooted in the failure to distinguish between the mainly legal concept of nationality and the broader, poli- tical concept of citizenship. Using this distinction, the paper analysis the evolution of German and American nationality laws over the last 200 years. The historical development of both legal structures shows strong communalities. With the emergence of the modern system of nation states, the attribution of nationality to newborn children is ascribed either via the principle of descent or place of birth. With regard to the naturalization of adults, there is an increasing ethni- zation of law, which means that the increasing complexities of naturalization criteria are more and more structured along ethnic ideas. Although every nation building process shows some elements of ethnic self-description, it is difficult to use the legal principles of ius sanguinis and ius soli as indicators of ethnic or non-ethnic modes of community building. ∗ For many suggestions and comments I thank the members of the German Study Group at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University, especially Cecilia Chessa, Stephen Hanson, Stephen Kalberg, Al- exander Schmidt-Gernig, Oliver Schmidkte, and Hans Joachim Schubert. For many helpful hints and remarks on the final draft of the paper I thank Lance Roberts and Barry Ferguson. -

U.S. Citizenship and the Naturalization Process

SAMPLE WEB PAGE CONTENT U.S. Citizenship and the Naturalization Process Becoming a U.S. citizen is a very important decision. Permanent residents have most of the rights of U.S. citizens. However, there are many important reasons to consider U.S. citizenship. When you become a citizen, you will receive all the rights of citizenship. You also accept all of the responsibilities of being an American. As a citizen you can: • Vote. Only citizens can vote in federal elections. Most states also restrict the right to vote, in most elections, to U.S. citizens. • Serve on a jury. Only U.S. citizens can serve on a federal jury. Most states also restrict jury service to U.S. citizens. Serving on a jury is an important responsibility for U.S. citizens. • Travel with a U.S. passport. A U.S. passport enables you to get assistance from the U.S. government when overseas, if necessary. • Bring family members to the United States. U.S. citizens generally get priority when petitioning to bring family members permanently to this country. • Obtain citizenship for children under 18 years of age. In most cases, a child born abroad to a U.S. citizen is automatically a U.S. citizen. • Apply for federal jobs. Certain jobs with government agencies require U.S. citizenship. • Become an elected official. Only citizens can run for federal office (U.S. Senate or House of Representatives) and for most state and local offices. • Keep your residency. A U.S. citizen’s right to remain in the United States cannot be taken away. -

The Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Origins of Birthright Citizenship

Eric Foner is the DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University. His books include Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (first published 1970), Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988), and The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010). This essay is based on Professor Foner’s Boden Lecture, which was delivered at Marquette University Law School on October 18, 2012, and which annually remembers the late Robert F. Boden, dean of the Law School from 1965 to 1984. This year’s lecture was part of Marquette University’s Freedom Project, a yearlong commemoration of the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation and the American Civil War. The Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Origins of Birthright Citizenship Eric Foner I want to begin by alluding to an idea I generally disdain as parochial and chauvinistic: American exceptionalism. Its specific manifestation here is the legal doctrine that every person born in this country is automatically a citizen. No European nation today recognizes birthright citizenship. The last to abolish it was Ireland a few years ago. Adopted as part of the effort to purge the United States of the legacy of slavery, birthright citizenship remains an eloquent statement about the nature of our society and a powerful force for immigrant assimilation. In a world where most countries limit access to citizenship via ethnicity, culture, religion, or the legal status of the parents, it sets the United States apart. The principle is one legitimate example of this country’s uniqueness. Yet oddly, those most insistent on the validity of the exceptionalist idea seem keenest on abolishing it. -

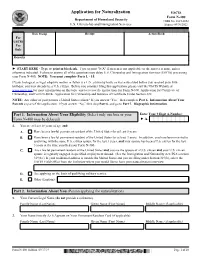

N-400, Application for Naturalization, Subscribed by Me, Including Corrections Number 1 Through ______, Are Complete, True, and Correct

Application for Naturalization USCIS Form N-400 Department of Homeland Security OMB No. 1615-0052 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Expires 09/30/2022 Date Stamp Receipt Action Block For USCIS Use Only Remarks ► START HERE - Type or print in black ink. Type or print "N/A" if an item is not applicable or the answer is none, unless otherwise indicated. Failure to answer all of the questions may delay U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) processing your Form N-400. NOTE: You must complete Parts 1. - 15. If your biological or legal adoptive mother or father is a U.S. citizen by birth, or was naturalized before you reached your 18th birthday, you may already be a U.S. citizen. Before you consider filing this application, please visit the USCIS Website at www.uscis.gov for more information on this topic and to review the instructions for Form N-600, Application for Certificate of Citizenship, and Form N-600K, Application for Citizenship and Issuance of Certificate Under Section 322. NOTE: Are either of your parents a United States citizen? If you answer “Yes,” then complete Part 6. Information About Your Parents as part of this application. If you answer “No,” then skip Part 6. and go to Part 7. Biographic Information. Part 1. Information About Your Eligibility (Select only one box or your Enter Your 9 Digit A-Number: Form N-400 may be delayed) ► A- 1. You are at least 18 years of age and: A. Have been a lawful permanent resident of the United States for at least 5 years.