Shifting the Anthropocentric Paradigms Embedded in Film and Classification (Ratings) Systems That Impact Apex Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nat Geo Wild March Schedule

Nat Geo Wild March Schedule (ET) Monday 2013/02/25 Tuesday 2013/02/26 Wednesday 2013/02/27 Thursday 2013/02/28 Friday 2013/03/01 Saturday 2013/03/02 Sunday 2013/03/03 (ET) 04:00 Hunter Hunted 2 04:00 Expedition Wild[Project 04:00 Hunter Hunted 2 「Kidnapped」 Kodiak] 「Kidnapped」 4 4 05:00 The Lady with 700 cats 05:00 Shark Men 3[#4 Tiger 05:00 Hunter Hunted 2 Bait] 「Shadow Stallkers」 5 5 06:00 Zoo Confidential[Special 06:00 Living Edens「BORNEO: 06:00 Swamp Men[#3 Break-In Delivery] An Island in the Clouds」 Bear] 6 6 07:00 Light At The Edge of 07:00 Lonely Planet: Roads 07:00 Swamp Men[#5 Bee The World 2「Heart of The Less Travelled[#9 Spain] Bomb] 7 Amazon」 7 08:00 Swamp Men[#2 Croc 08:00 Light At The Edge of 08:00 Swamp Men 3[#5 Escape] The World 2「Magic Mountain」 Restroom Rattler] 8 8 09:00 Shane 09:00 Light At The Edge of 09:00 Zoo Confidential[Special Untamed[Everglades] The World 2「People of the Delivery] 9 Windhorse」 9 10:00 information 10:00 Light At The Edge of 10:00 Zoo The World 2「Keepers of The Confidential[Operation Ocelot] 10 10 10:30 Caught In The Act GPU Dream」 Reversions[#5 Blood Battles] 11:00 Light At The Edge of 11:00 Dangerous Encounters The World 2「Heart of The W/ Brady Barr S5「Canibal 11 11 11:30 Dog Whisperer Amazon」 Squid」 #19 12:00 African Mega Flyover 12:00 Dangerous Encounters W/ Brady Barr S6 [Snakebot] 12 12 12:30 Man vs. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

2015, Volume 8

V O L U M E 8 2015 D E PAUL UNIVERSITY Creating Knowledge THE LAS JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP CREATING KNOWLEDGE The LAS Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship 2015 EDITOR Warren C. Schultz ART JURORS Adam Schreiber, Coordinator Laura Kina Steve Harp COPY EDITORS Stephanie Klein Rachel Pomeroy Anastasia Sasewich TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 Foreword, by Interim Dean Lucy Rinehart, PhD STUDENT RESEARCH 8 S. Clelia Sweeney Probing the Public Wound: The Serial Killer Character in True- Crime Media (American Studies Program) 18 Claire Potter Key Progressions: An Examination of Current Student Perspectives of Music School (Department of Anthropology) 32 Jeff Gwizdalski Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Insurance Coverage for Young Adults (Department of Economics) 40 Sam Okrasinski “The Difference of Woman’s Destiny”: Female Friendships as the Element of Change in Jane Austen’s Emma (Department of English) 48 Anna Fechtor Les Musulmans LGBTQ en Europe Occidentale : une communauté non reconnue (French Program, Department of Modern Languages) 58 Marc Zaparaniuk Brazil: A Stadium All Its Own (Department of Geography) 68 Erin Clancy Authority in Stone: Forging the New Jerusalem in Ethiopia (Department of the History of Art and Architecture) 76 Kristin Masterson Emmett J. Scott’s “Official History” of the African-American Experience in World War One: Negotiating Race on the National and International Stage (Department of History) 84 Lizbeth Sanchez Heroes and Victims: The Strategic Mobilization of Mothers during the 1980s Contra War (Department -

Adam Sandler: Mentor Of

ADAM SANDLER: MENTOR OF MIDDLE-CLASS MASCULINITY AND MANHOOD A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Stanislaus In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History By Kathleen Boone Chapman April 2014 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL ADAM SANDLER: MENTOR OF MASCULINITY AND FATHERHOOD by Kathleen Boone Chapman Signed Certification of Approval Page is on file with the University Library Dr. Bret E. Carroll Date Professor of History Dr. Samuel Regalado Date Professor of History Dr. Marcy Rose Chvasta Date Professor of Communications © 2014 Kathleen Boone Chapman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEDICATION I am dedicating this work to my three dear friends: Ronda James, Candace Paulson, and Michele Sniegoski. Ronda’s encouragement and obedience to the Lord gave me what I needed to go back to school with significant health issues and so late in life. Candace, who graduated from Stanford “back in the olden days,” to quote our kids, inspired me to follow my dream and become all God wants me to be. Michele’s long struggle with terminal kidney disease motivated me to keep living in spite of my own health issues. We have laughed and cried together over many years, but all of you have given me strength to carry on. Sorry two of you made it to heaven before I could get this finished. I also want to give credit to my husband of forty years who has been a faithful breadwinner, proof-reader, and a paragon of patience. What more could any woman ask for? He has also put up with me yelling at my computer and cursing Bill Gates – A LOT. -

Anaconda 2 Pelicula Completa Em Espa

Anaconda 2 pelicula completa em espa Continue Anacondas: Blood Hunt OrchidAncondas Title: Hunting for a Bloody Orchid (Spain)Anaconda 2: In Search of Bloody Orchid (Hispanoamerica)Technical Data SheetDwight H. LittleProduction Vern HarrahAcobus RoseSusan RuskinGuion Hans Bauermin Tyson-ChewFotography Stephen F. WindonMontaje Marcus D'ArcyProtagonists Johnny MessnerKaDee StricklandMatthew MarsdenNicolas Gonzalez UrdKarl YuneSalli RichardsonMorris Chestnut View of all credits (IMDb data and figuresPaUDer Terrorist Action 97 minutes EnglishCompaniesoraProduct Screen GemsDistribution Columbia Pictures : Blood Hunt OrchidAnaconda 3: Offspring (2008)IMDbFicha tab in FilmAffinity edit wikidata data Anacondas: Hunting for a Bloody Orchid is an American film directed by Dwight H. Little in 2004, is the second film in the Anaconda franchise and stars Johnny Messner , KaDee Strickland, Morris Chestnut, Eugene Bird, Nicholas Gonzalez, Matthew Marsden, Sally Richardson, Andy Anderson and Carl Yune. It premiered seven years after Anaconda in 1997, and its seeds Anaconda 3: Offspring and his last film Anacondas: Trail of Blood in 2009 premiered in 2008. An argument team of researchers from the pharmaceutical company Wexel Hall is heading to the island of Borneo to find a species of orchid known as bloody orchid, a flower that they believe can be used as a kind of source of immortality and whose health benefits will be shocking. While the team's leadership, Bill Johnson (Johnny Messner) doubts which path to take, Jack Byron (Matthew Marsden) encourages them to go down the road. The team ends up crossing the waterfall and they must vade the river. A giant anaconda emerges from the water and eats Dr. Ben Douglas (Nicholas Gonzalez) as a whole, while the rest of the team manages to escape. -

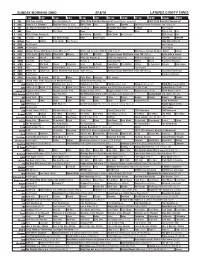

Sunday Morning Grid 3/18/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/18/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) 2018 NCAA Basketball Tournament Second Round: Teams TBA. 2018 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Journey Journey Golf Arnold Palmer Invitational, Final Round. (N) 5 CW Los Angeles Marathon Runners compete in Los Angeles Marathon. (N) Å Marathon Post Show In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Way of Life Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program NASCAR NASCAR 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Lake City (2008) (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Retire Safe & Secure With Ed Slott (TVG) Å Rick Steves Special: European Easter Orman 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Retire Safe & Secure 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Planeta U Calimero (TVG) Mickey Manny República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Cine-Excess 13 Delegate Abstracts

Cine-Excess 13 Delegate Abstracts Alice Haylett Bryan From Inside to The Hills Have Eyes: French Horror Directors at Home and Abroad In an interview for the website The Digital Fix, French director Pascal Laugier notes the lack of interest in financing horror films in France. He states that after the international success of his second film Martyrs (2008) he received only one proposition from a French producer, but between 40 and 50 propositions from America: “Making a genre film in France is a kind of emotional roller-coaster” explains Laugier, “sometimes you feel very happy to be underground and trying to do something new and sometimes you feel totally desperate because you feel like you are fighting against everyone else.” This is a situation that many French horror directors have echoed. For all the talk of the new wave of French horror cinema, it is still very hard to find funding for genre films in the country, with the majority of French directors cutting their teeth using independent production companies in France, before moving over to helm mainstream, bigger-budget horrors and thrillers in the USA. This paper will provide a critical overview of the renewal in French horror cinema since the turn of the millennium with regard to this situation, tracing the national and international productions and co-productions of the cycle’s directors as they navigate the divide between indie horror and the mainstream. Drawing on a number of case studies including the success of Alexandre Aja, the infamous Hellraiser remake that never came into fruition, and the recent example of Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge, it will explore the narrative, stylistic and aesthetic choices of these directors across their French and American productions. -

1 Production Information in Just Go with It, a Plastic Surgeon

Production Information In Just Go With It, a plastic surgeon, romancing a much younger schoolteacher, enlists his loyal assistant to pretend to be his soon to be ex-wife, in order to cover up a careless lie. When more lies backfire, the assistant's kids become involved, and everyone heads off for a weekend in Hawaii that will change all their lives. Columbia Pictures presents a Happy Madison production, Just Go With It. Starring Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler, Jack Giarraputo, and Heather Parry. Screenplay by Allan Loeb and Timothy Dowling. Based on ―Cactus Flower,‖ Screenplay by I.A.L. Diamond, Stage Play by Abe Burrows, Based upon a French Play by Barillet and Gredy. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Allen Covert, Tim Herlihy, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson-Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Just Go With It has been rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for Frequent Crude and Sexual Content, Partial Nudity, Brief Drug References and Language. The film will be released in theaters nationwide on February 11, 2011. 1 ABOUT THE FILM At the center of Just Go With It is an everyday guy who has let a careless lie get away from him. ―At the beginning of the movie, my character, Danny, was going to get married, but he gets his heart broken,‖ says Adam Sandler. -

BEDTIME STORIES Bobbi

THIS MATERIAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT http://www.wdsfilmpr.com © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. disney.com/BedtimeStories WALT DISNEY PICTURES Unit Production Manager . GARRETT GRANT Presents First Assistant CREDITS Director . DANIEL SILVERBERG A Second Assistant Director . CONTE MATAL HAPPY MADISON Creatures Designed by. CRASH MCCREERY Production Production Supervisor . ROBERT WEST A CAST CONMAN & IZZY Skeeter Bronson. ADAM SANDLER Production Jill . KERI RUSSELL Kendall . GUY PEARCE An Mickey. RUSSELL BRAND OFFSPRING Barry Nottingham . RICHARD GRIFFITHS Production Violet Nottingham. TERESA PALMER Aspen. LUCY LAWLESS Wendy . COURTENEY COX Patrick . JONATHAN MORGAN HEIT BEDTIME STORIES Bobbi . LAURA ANN KESLING Marty Bronson . JONATHAN PRYCE Engineer . NICK SWARDSON A Film by Mrs. Dixon . KATHRYN JOOSTEN ADAM SHANKMAN Ferrari Guy. ALLEN COVERT Hot Girl . CARMEN ELECTRA Young Barry Nottingham . TIM HERLIHY Directed by . ADAM SHANKMAN Young Skeeter . THOMAS HOFFMAN Screenplay by . MATT LOPEZ Young Wendy . ABIGAIL LEONE DROEGER and TIM HERLIHY Young Mrs. Dixon. MELANY MITCHELL Story by. MATT LOPEZ Young Mr. Dixon . ANDREW COLLINS Produced by. ANDREW GUNN Donna Hynde. AISHA TYLER Produced by . ADAM SANDLER Hokey Pokey Women. JULIA LEA WOLOV JACK GIARRAPUTO DANA MIN GOODMAN Executive Producers . ADAM SHANKMAN SARAH G. BUXTON JENNIFER GIBGOT CATHERINE KWONG ANN MARIE SANDERLIN LINDSEY ALLEY GARRETT GRANT Bikers. BLAKE CLARK Director of BILL ROMANOWSKI Photography . MICHAEL BARRETT Hot Dog Vendor . PAUL DOOLEY Production Designer . LINDA DESCENNA Birthday Party Kids . JOHNTAE LIPSCOMB Edited by. TOM COSTAIN JAMES BURDETTE COWELL MICHAEL TRONICK, A.C.E. Angry Dwarf . MIKEY POST Costume Designer . RITA RYACK Gremlin Driver . SEBASTIAN SARACENO Visual Effects Cubby the Supervisor. JOHN ANDREW BERTON, JR. Home Depot Guy . -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

Blu-Ray Players May Play Either Dvrs Or Dvds. DVD Players Can Only Play Dvds

___ DVD 0101 - 2 Guns Rated R ___ DVD 0644 - 12 Strong Rated R ___ DVD 0100 - 12 Years A Slave Rated R ___ DVD 0645 - The 15:17 to Paris Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0102 - 21 Jump Street Rated R ___ DVD 0314 - 22 Jump Street Rated R ___ DVR 0315 - 22 Jump Street Rated R ___ DVD 0316 - 23 Blast Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0577 - The 33 Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0103 - 42: The Jackie Robinson Story PG-13 ___ DVD 0964 - 101 Dalmations Rated G ___ DVR 0965 - 101 Dalmations Rated G ___ DVR 0966 - 2001: A Space Odyssey (Blu-Ray) Rated G ___ DVD 0108 - About Time Rated R ___ DVD 0107 - Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter R ___ DVD 0242 - The Adjustment Bureau Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0646 - Adrift (Based on the a True Story) PG-13 ___ DVD 0243 - The Adventures Of Tintin Rated PG ___ DVD 0706 - The Aftermath Rated R ___ DVD 0319 - Age Of Adaline Rated PG-13 Blu-Ray players may play either DVRs or DVDs. DVD players can only play DVDs. 1 | SD BTBL Descriptive Video Order Form: 2020 Catalog ___ DVR 0320 - Age Of Adaline Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0995 - Aladdin (Animated) Rated G ___ DVR 0996 - Aladdin (Animated) Rated G ___ DVD 0997 - Aladdin (live action) Rated PG ___ DVR 0998 - Aladdin (live action) Rated PG ___ DVD 0321 - Alexander And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Rated PG ___ DVD 0109 - Alice In Wonderland Rated PG ___ DVD 0723 - Alita: Battle Angel Rated PG-13 ___ DVR 0724 - Alita: Battle Angel Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0725 - All Is True Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0473 - Almost Christmas Rated PG-13 ___ DVR 0322 - Aloha (Blu-Ray) Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0726 - Alpha Rated PG-13 ___ DVD 0111 - Alvin And The Chipmunks: The Squeakquel Rated PG ___ DVD 0110 - Alvin And The Chipmunks: Chipwrecked Rated G ___ DVD 0474 - Alvin And The Chipmunks: The Road Chip Rated PG ___ DVD 0244 - The Amazing Spider-Man Rated PG-13 Blu-Ray players may play either DVRs or DVDs. -

Grown-Ups Film Production Notes

PRODUCTION NOTES Release Date: June 24 th , 2010 Running time: 102 min Rating: PG 1 Grown Ups , Starring Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, and Rob Schneider, is a full-on comedy about five men who were best friends when they were young kids and are now getting together with their families on the Fourth of July weekend for the first time in thirty years. Picking up where they left off, they discover that growing older doesn’t mean growing up. Columbia Pictures presents in association with Relativity Media a Happy Madison production, a film by Dennis Dugan, Grown Ups . The film stars Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, Rob Schneider, Salma Hayek, Maria Bello, and Maya Rudolph. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler and Jack Giarraputo. Written by Adam Sandler & Fred Wolf. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Tim Herlihy, Allen Covert, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson- Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Credits are not final and subject to change. 2 ABOUT THE FILM Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, and Rob Schneider head up an all-star comedy cast in Grown Ups , the story of five childhood friends who reunite thirty years later to meet each others’ families for the first time. When their beloved former basketball coach dies, they return to their home town to spend the summer at the lake house where they celebrated their championship years earlier.