Paper 14; Module 11; E Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

Mahatma Gandhi University

MODEL I BA Programme in English Language and Literature Syllabi for Core Courses COURSE-1 METHODOLOGY OF HUMANITIES AND LITERATURE Course Code ENCR1 Title of the course METHODOLOGY OF HUMANITIES AND LITERATURE Semester in which the I course is to be taught No. of credits 4 No. of contact hours 108 1. AIM OF THE COURSE o The course is intended to introduce the student to the interrelationship between paradigms of social formation 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE On completion of the course, the student should be able; o To know and appreciate the location of literature within humanities o To establish connections across frontiers of disciplines o To critically engage with culture , gender and marginality o To become acquainted with narration and representatio 3. COURSE OUTLINE Module (1) 54 HOURS A : Understanding the humanities - the scientific method – how humanities explore reality – the natural and social sciences – facts and interpretation –study of natural and subjective world- tastes, values and belief systems B: Language ,culture and identity- language in history- language in relation to caste, class, race and gender- language and colonialism. 53 C: Narration and representation- what is narration-narrative modes of thinking- narration in literature, philosophy and history- reading. Module (2) 54 HOURS The following essays are to be dealt with intensively in relation with the methodological questions raised above(module 1) 1.Peter Barry : “Theory before ‘theory’ – liberal humanism”. Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. New York,Manchester. 1995. 11-38 2.Sudhir Kakar, Katharina Kakar. “The Hierarchical Man” The Indians: Portrait of a People. -

About the Contributors

207 About the Contributors Deepanjali Mishra earned her PhD in English from Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Motivating and Talented English Professor driven to inspire students to pursue academic and personal excellence. Consistently driven towards extensive research and exceptional track record towards contribution to various publication work. Energetic, highly career oriented and focused for attainment of goal. Her Area of interest includes Feminism and Gender Stud- ies, Sociology, Linguistics, Management. She has over 15 years of teaching and research experience. She has published a book titled I Am a Woman with Bahri Publishers New Delhi. She is the guest editor of Research Chronicler, Literaria and Indian Journal of Communication. She has published over 26 research papers in reputed international journals and has presented her papers in various International conferences in India and abroad like IIT, IIM, South Korea, China, and Nepal. * * * Stephanie Bianchi holds a Bachelor in Molecular Biology with special- ization in Genetic Engineering from the University of Graz, Austria. Master in Molecular and Cellular Neurobiology from the University of Bordeaux, France and University of Coimbra, Portugal. Co-founder and Co-director of Mindful Guatemala Foundation. Certified Mindfulness and Meditation Trainer. Madhumita Chanda teaches English Language and Professional Values and Ethics in the Dept. of Humanities, Heritage Institute of Technology, Kolkata. She is also attached to the Dept. of Comparative Language and Literature, C.U. as Guest Teacher. Her doctoral thesis is on Contemporary Translation Theories. She has published a book on translation theory and practice and many research papers in various national and international journals on comparative literature and translation studies. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English Vol

AboutUs: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ ContactUs: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ EditorialBoard: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 10, Issue-VI, December 2019 ISSN: 0976-8165 Silences in the Poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra Dr. N. K. Sharma Lecturer in English (Retd.) Hindu College (P.G) Sonepat, Haryana. Article History: Submitted-04/11/2019, Revised-14/12/2019, Accepted-16/12/2019, Published-31/12/2019. Abstract: Silences are all-pervasive in the poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra and they originate from myriad sources. The chief sources of silences are loneliness, darkness, ash, stone, past, ancient history and myths.They have enormouscreative potential which constitutes Jayanta’s poetic vision. Silences are more evocative than speechand are the most effective meansof communication. They radically slash the role of words in loneliness and darkness. Silences act like an antenna for the poet to reveal his subconscious mind fearlessly which he had previously withheld in social discourse. They have given him an ample opportunity to authentically redefine his relationships with the members of his family, friends and others. Silences help Jayanta Mahapatra to correlate the present with the ancient past by means memories or reveries. Silences of the ancient myths help the poet to dramatize the modern tragic times in a frank and unbiased manner. Keywords: Silence, Loneliness, Darkness, Ash, Stone and Myth. -

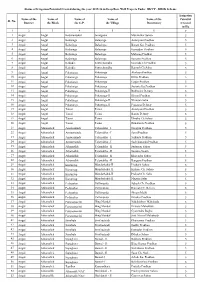

Sl. No. Name of the District Name of the Block Name of the G.P. Name Of

Status of Irrigation Potential Created during the year 2015-16 in Deep Bore Well Projects Under BKVY - DBSK Scheme Irrigation Name of the Name of Name of Name of Name of the Potential Sl. No. District the Block the G.P. the Village Beneficiary Created in Ha. 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Angul Angul Badakantakul Jamugadia Muralidhar Sahoo 5 2 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Antaryami Pradhan 5 3 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Basant Ku. Pradhan 5 4 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Kumudini Pradhan 5 5 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Maharag Pradhan 5 6 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Santanu Pradhan 5 7 Angul Angul Kakudia Santarabandha Govinda Ch.Pradhan 5 8 Angul Angul Kakudia Santarabandha Ramesh Ch.Sahu 5 9 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Akshaya Pradhan 5 10 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Dillip Pradhan 5 11 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Gagan Pradhan 5 12 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Susanta Ku.Pradhan 5 13 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Budhadev Dehury 5 14 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Khirod Pradhan 5 15 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Niranjan Sahu 5 16 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Prasanna Dehury 5 17 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Antaryami Pradhan 5 18 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Banita Dehury 5 19 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Dhruba Ch.Sahoo 5 20 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Runakanta Pradhan 5 21 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Narayan Pradhan 5 22 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Saroj Pradhan 5 23 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Srikanta Pradhan 5 24 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Sachidananda Pradhan 5 25 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Sudarsan Sahoo 5 26 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Susanta Swain 5 27 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Khirendra Sahoo 5 28 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Banguru Pradhan 5 29 Angul Athamalick Kurumtap Mandarbahal-II Pitabash Sahoo 5 30 Angul Athamalick Kurumtap Mandarbahal-II Kishore Ch. -

Independent Indian Society As Portrayed in the Poems of Keki N

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.6.Issue 2. 2018 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (April-June) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE POST – INDEPENDENT INDIAN SOCIETY AS PORTRAYED IN THE POEMS OF KEKI N. DARUWALLA M. RAJALAKSHMI Assistant Professor, Department of English, VELS Institute of Science, Technology and Advanced Studies, Chennai ABSTRACT With the attainment of Independence from the British rule in 1947, India placed its first step towards shaping its progress. India starts emerging as one of the powerful nations in the world. Post Independent India can be seen as an amalgamation of both the dark and the bright sides. While some writers are busy in portraying the positive, bright side of the Indian society, Daruwalla critically highlights the dark and negative aspects of it. As he himself is a police official, he confronts violence, bloodshed, riot, murder, social evils, etc., right before his eyes and he records his official experiences in his poems. By portraying sick India with sick people using weapons like satire and irony, Daruwalla succeeds in bringing awareness in the minds of the people. This paper aims to analyse how Daruwalla critically depicts Post-Independent Indian society in his poems. Keywords: Post – Independent India, corruption, social evils, poverty, satire . Indian English Literature is a little more women, etc., also form the themes of their poems. than hundred and fifty years old. The British people Keki N. Daruwalla is one of the experts in depicting gave rise to “a new climate of thought and purpose” the contemporary Post-Independent Indian society. -

NAAC Re-Accreditation Self Study Report

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695 034 SELF STUDY REPORT SUBMITTED FOR REACCREDITATION TO NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE - 560 072 2 NAAC Re-Accreditation Committee University College, Thiruvananthapuram Dr. B. S. Mohanachandran (Principal) Patron (Ex-officio) Dr. R. Anilkumar (Dept. of Geography) General Convenor Dr. K. P. Jaikiran (Dept. of Geology) Co-ordinator, IQAC Members Dr.S. Unnikrishnan Nair - (Vice-Principal) Sri. G. Rajeev - (Dept. of Chemistry) Sri. K. Gopalakrishnan - (Dept. of English) Dr. Thomas Kuruvilla - (Dept. of English) Dr. Francis Sunny - (Dept. of Zoology) Dr. Philip Samuel - (Dept. of Statistics) Sri. M.B. Salim - (Dept. of Geography) Sri. P. Surendran - (Dept. of Physical Education) 3 Contents Page No. PREFACE Part I - INSTITUTIONAL DATA 01 - 44 Profile of the Institution Criterion wise input Profiles of the departments Part II - EVALUATIVE REPORT 45 – 400 Stand out facts Executive summary Criterion wise evaluative report Evaluative report of Departments Declaration by the Principal 4 PREFACE University College, Thiruvananthapuram (estd.1866) occupies a position of eminence among the colleges in the state of Kerala and that of a hallowed alma mater among the millions of students, including luminaries like the late Dr K R Narayanan, the former President of India and Dr. G Madhavan Nair, former Director, Indian Space Research Organisation. The college, situated in the heart of Trivandrum, the capital city of Kerala is unique in more than one respect: more than sixty per cent of its teachers are research degree holders; the college has fourteen research departments offering M.Phil. and PhD; and its student strength of 3200* includes enrolment from all social classes. -

JAYANTA MAHAPATRA (B.L928)

POETRY OF JAY ANT A MAHAPATRA: A STUDY IN THE PATTERN OF IMAGERY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISl-I Submitted by: 711\.TT A l\lfTTR !l L ..... LI. ...l "'I .l..i l. j.1'J.J. J. J.'J \. Under the supervision of: Prof. B. K. BANERJEE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJARAMMOHANPUR DARJEELING November, 2006 eo~z 83::1 1 t S202:0Z d789W G·IZ8 ·Ja;~[~ d POETRY OF JAY ANT A MAHAPATRA: A STUDY IN THE PATTERN OF IMAGERY submiltccl lJy: Zinia Mitra l!nder the supervision of: Prof.B.K.Bancrjce Department of English University of North Bengal Eaja Eammohanpur, Darjeeling. November, 2006. Certification Certified that this is a bona fide work. Signature: , R~:;t '4. 8c:1.~-:j~, Date: 16. IJ. d Prof..B.K.Banerjee Department of English North Bengai University JAYANTA MAHAPATRA (b.l928) Crossing life . often the tired lines seem to run under my palms. Someone talks of a work of arl, looking into its little secret: Oayanta Mahapatra. 1\ Hain of Hites : 36) CONTENTS Pages Preface 1- JX Introduction. 1-12 Chapter I. Imagery -- Concept and Function 13-48 Chapter II. Mapping Mahapatra 49-91 Chapter Ill. Pattern of Imagery in Jayanta Mahapatra's Poetry (i} Experimental Stage. 92-114 (ii) Experiential Stage. 115-161 Chapter IV. The Poet as a Social Critic. 1f)2-187 Chapter V. Jayanta Mahapatra Vis-a vis His Contemporaries 188-238 Conclusion. 239- 246 Works Cited & Bibliography 24 7 - 259 Appendix PF~EFACE You said poetry cont<1ins us both. -

The Being of Bhasha: a General Introduction (Volume 1, Part 2) Chief Editor: G.N

The Being of Bhasha: A General Introduction (Volume 1, Part 2) Chief Editor: G.N. Devy The first volume of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India brings to the reader the journey undertaken in 2010, by a group of visionaries led by G.N. Devy to document the languages of India as they existed then. The aim of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India was to document the languages spoken in India’s remotest corners. India’s towns and cities too have found a voice in this survey. The Being of Bhasha forms the introduction to the series. 2014 978-81-250-5488-7 152 pp ` 790 Rights: World 978-81-250-5775-8 (E-ISBN) The Languages of Jammu & Kashmir (Volume 12, Part 2) Volume Editor: Omkar N. Koul The twelfth volume of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India documents the languages of the State of Jammu & Kashmir. The book is divided into three parts—the first part covers the scheduled languages, Dogri and Kashmiri; the second part, the non-scheduled and minor languages; and the third part is devoted to Sanskrit, Persian, Hindi and Urdu which have played an important role in the state and also influenced local languages. Though Urdu is the official state language, of late there has been a shift in the linguistic profile in Jammu & Kashmir as there have been some linguistic movements towards inclusion of local languages in various domains. In the discussions about the languages, there is information about their contemporary status, their historical evolution and structural aspects. The linguistic map included in the volume also gives an idea of areas where the main languages are spoken. -

The Abandoned British Cemetery at Balasore

16 MM VENKATESHWARA CONTEMPORARY INDIAN OPEN UNIVERSITY WRITING IN ENGLISH www.vou.ac.in CONTEMPORARY INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH IN WRITING INDIAN CONTEMPORARY CONTEMPORARY INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH [M.A. ENGLISH] VENKATESHWARA OPEN UNIVERSITYwww.vou.ac.in CONTEMPORARY INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH MA [ENGLISH] BOARD OF STUDIES Prof Lalit Kumar Sagar Vice Chancellor Dr. S. Raman Iyer Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. Anil Kr. Jaiswal Professor Dr. Shantanu Siuli Assistant Professor Dr.Mohammad Danish Siddiqui Assistant Professor CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Tauha Khan Registrar Author Sanjiv Nandan Prasad, Associate Professor, Department of English, Hansraj College, University of Delhi Copyright © Sanjiv Nandan Prasad, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher, its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. -

Jayanta Mahapatra - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Jayanta Mahapatra - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Jayanta Mahapatra(22 October 1928 -) Jayanta Mahapatra is one of the best known Indian English poets. Perhaps any discussion on Indian English Poetry is incomplete without reference to his poetical works. Physicist, bilingual poet and essayist, Jayanta Mahapatra holds the distinction of being the first Indian English poet to have received the Sahitya Akademi Award (1981) for Relationship. In 2009 he was awarded by Government of India with "Padmashree Award", country's most prestigious award for civilian citizen for his out standing contribution to the field of literature. <b> Birth and Early Life </b> Jayanta Mahapatra, born on 22 October 1928 in Cuttack ( India ), belongs to a lower middle-class family. He had his early education at Stewart school, Cuttack . After a first class Master's Degree in Physics, he joined as a teacher in 1949 and served in different Government colleges of Orissa. <b> Later Life </b> All his working life, he taught physics at different colleges in Orissa. He retired in 1986. Mahapatra has authored 18 books of poems. He started writing poetry at the age of thirty-eight, quite late by normal standards. Mahapatra's tryst with the muse came rather late in life. He published his first poems in his early 40s. The publication of his first book of poems, Svayamvara and Other Poems, in 1971 was followed by the publication of Close the Sky, Ten By Ten. His collections of poems include A Rain of Rites, Life Signs and A Whiteness of Bone.