One Person Made a Difference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tributes to Hon. Edward E. Kaufman

TRIBUTES TO HON. EDWARD E. KAUFMAN VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:29 May 21, 2012 Jkt 064812 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE10\64812.TXT KAYNE VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:29 May 21, 2012 Jkt 064812 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE10\64812.TXT KAYNE Edward E. Kaufman U.S. SENATOR FROM DELAWARE TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:29 May 21, 2012 Jkt 064812 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE10\64812.TXT KAYNE congress.#15 Edward E. Kaufman VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:29 May 21, 2012 Jkt 064812 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE10\64812.TXT KAYNE 64812.001 S. DOC. 111–33 Tributes Delivered in Congress Edward E. Kaufman United States Senator 2009–2010 ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2012 VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:29 May 21, 2012 Jkt 064812 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE10\64812.TXT KAYNE Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:29 May 21, 2012 Jkt 064812 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE10\64812.TXT KAYNE CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. v Farewell to the Senate ............................................................................. ix Proceedings in the Senate: Tributes by Senators: Akaka, Daniel K., of Hawaii ..................................................... 17 Alexander, Lamar, of Tennessee ............................................... 10 Burris, Roland W., of Illinois .................................................... 9 Conrad, Kent, of North Dakota ................................................ -

PLS 101 - Lecture 17

PLS 101 - Lecture 17 A couple of things I want to talk about. Weíll bring up the PowerPoint but I also wanted to show you something here about primaries as well. You know, we just had a recent election. If you think about it right now, here we are at the very beginning of March. Go back to a year from now. Again, this is gonna be somewhat dated on the TV, I think. If you go back a year from now, a year ago, what was going on in terms of the presidential race? Think about what was happening in February and March of last year. What was happening? If you picked up the paper, what would you have seen? [Inaudible student response] Yes. Primaries were going on. These were some of the individuals who were running for president about this time last year. They were going into the primaries. Dick Gephardt from Missouri was running for president. We forget about these names so quickly. John Edwards. Howard Dean. Joe Lieberman, a senator from Connecticut. Al Sharpon. Wesley Clark and John Kerry among others who were all running for president. They wanted to pursue and become the Democratic nominee for president. Who was running in the Republican primaries? Who else? Unopposed. Thatís right. It was just Bush. That was a trick question. All right. Now, I bring all this up because what we saw happening beginning in January all the way through May or June were state by state primaries. Weíre gonna talk about primaries quite a bit today, but there were state by state elections that were taking place to determine who was gonna be the nominee for president. -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State?

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State? A Thesis Presented to The Division of History and Social Sciences Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Daniel Krantz Toffey May 2007 Approved for the Division (Political Science) Paul Gronke Acknowledgements Acknowledgements make me a bit uneasy, considering that nothing is done in isolation, and that there are no doubt dozens—perhaps hundreds—of people responsible for instilling within me the capability and fortitude to complete this thesis. Nonetheless, there are a few people that stand out as having a direct and substantial impact, and those few deserve to be acknowledged. First and foremost, I thank my parents for giving me the incredible opportunity to attend Reed, even in the face of staggering tuition, and an uncertain future—your generosity knows no bounds (I think this thesis comes out to about $1,000 a page.) I’d also like to thank my academic and thesis advisor, Paul Gronke, for orienting me towards new horizons of academic inquiry, and for the occasional swift kick in the pants when I needed it. In addition, my first reader, Tamara Metz was responsible for pulling my head out of the data, and helping me to consider the “big picture” of what I was attempting to accomplish. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Charles McKinley Fund for providing access to the Cooperative Congressional Elections Study, which added considerable depth to my analyses, and to the Fautz-Ducey Public Policy fellowship, which made possible the opportunity that inspired this work. -

Joe Lieberman

A Conversation with JOE LIEBERMAN Senator Joseph I. Lieberman was the 2000 Democratic nominee for vice president alongside presidential candidate Al Gore. From 1989 until 2013, Lieberman served as senator from Connecticut, first as a member of the Democratic Party and then, from 2006, as an independent. Previously he served in the Connecticut state senate and as the state attorney general. In this conversation, Kristol and Lieberman discuss key moments of Lieberman’s career in public service from his ascent in Connecticut politics to Gore-Lieberman in 2000, as well as his successful Senate campaign as an independent in 2006. Lieberman also reflects on colleagues and contemporaries such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Bob Dole, John McCain, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush. On Gore-Lieberman 2000, Lieberman says: “It vindicated Gore's confidence that America was not going to judge me based on my religion. And it's a wonderful thing to be able to say.” On his support for the Iraq War, Lieberman says: “It really alienated me from a lot of the left of the Democratic Party and frankly some of the middle, too, who were anti-war and anti-Bush... A lot of them read it not that I was sticking with the Iraq war for reasons of foreign policy and American national interests but somehow I was doing it for President Bush...the fact that he and I might have...reached the same policy conclusions never dawned on a lot of these people.” On Two Democratic Presidents, Lieberman says: “Obama has very smart ideas but has not worked the Congress very well and people, even those who are loyal to him, don't see him, don't talk to him very much...Clinton, he'd call you and the problem was ‘how do I get him off the phone?’” Chapter Links to JOE LIEBERMAN Conversation Gore-Lieberman 2000 From Connecticut to Washington Lieberman’s 2006 Senate Race On Senators and Presidents 350 WEST 42ND STREET, SUITE 37C, NEW YORK, NY 10036 . -

The State of the Presidential Appointment Process

S. Hrg. 107–118 THE STATE OF THE PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTMENT PROCESS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 4 AND 5, 2001 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–498 PDF WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 08:53 Mar 13, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 72498.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: SAFFAIRS COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine CARL LEVIN, Michigan GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire MAX CLELAND, Georgia ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JEAN CARNAHAN, Missouri HANNAH S. SISTARE, Staff Director and Counsel DAN G. BLAIR, Senior Counsel ROBERT J. SHEA, Counsel JOHANNA L. HARDY, Counsel JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Democratic Staff Director and Counsel SUSAN E. PROPPER, Democratic Counsel DARLA D. CASSELL, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 08:53 Mar 13, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 72498.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: SAFFAIRS C O N T E N T S Page Opening statements: Senator Thompson ............................................................................................ 1, 49 Senator Akaka .................................................................................................. 2 Senator Voinovich ............................................................................................ -

All Results Official Election Returns State of Missouri General Election Tuesday, November 07, 2000 As Announced B

All Results Official Election Returns State of Missouri General Election Tuesday, November 07, 2000 As announced by the Board of State Canvassers on Monday, December 04, 2000 Office Candidate Name Votes % Of Votes U.S. President And Vice President Al Gore, Joe Lieberman DEM 1,111,138 47.1% George W. Bush, Dick Cheney REP 1,189,924 50.4% Harry Browne, Art Olivier LIB 7,436 .3% Howard Phillips, J. Curtis Frazier CST 1,957 .1% Pat Buchanan, Ezola Foster REF 9,818 .4% John Hagelin, Mike Tompkins NAT 1,104 .0% Ralph Nader, Winona LaDuke GRE 38,515 1.6% Total Votes 2,359,892 U.S. Senator Carnahan, Mel DEM 1,191,812 50.5% Ashcroft, John REP 1,142,852 48.4% Stauffer, Grant Samuel LIB 10,198 .4% Foley, Hugh REF 4,166 .2% Dockins, Charles NAT 1,933 .1% Taylor, Evaline GRE 10,612 .4% Kennedy, Alyson WI 8 .0% Day, Darrel WI 5 .0% Total Votes 2,361,586 Governor Holden, Bob DEM 1,152,752 49.1% Talent, Jim REP 1,131,307 48.2% Swenson, John M. LIB 11,274 .5% Smith, Richard L. CST 3,142 .1% Kline, Richard Allen REF 4,916 .2% Reed, Lavoy (Zaki Baruti) GRE 9,008 .4% Rice, Larry IND 34,431 1.5% Total Votes 2,346,830 Lieutenant Governor Maxwell, Joe DEM 1,201,959 52.1% Bailey, Wendell REP 1,014,446 44.0% Horras, Phillip W. LIB 20,345 .9% Wells, Bob CST 15,681 .7% Weber, George D. REF 17,859 .8% Griffard, Patricia A. -

Face the Nation

© 2005 CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION. " CBS News FACE THE NATION Sunday, December 4, 2005 GUEST: Senator JOHN KERRY, (D-MA) Foreign Relations Committee MODERATOR: BOB SCHIEFFER - CBS News This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS 202-457-4481 BURRELLE'S INFORMATION SERVICES / 202-419-1859 / 800-456-2877 Face the Nation (CBS News) - Sunday, December 4, 2005 1 BOB SCHIEFFER, host: Today on FACE THE NATION, Senator John Kerry in his first Sunday interview since January. A shift of fewer than 100,000 votes in Ohio and John Kerry would have become president. So how would he handle Iraq today and will he run again? We'll put those questions and more to the senator from Massachusetts. Then I'll have a final word on paying for good news. But first, Senator Kerry, Iraq and politics on FACE THE NATION. Announcer: FACE THE NATION with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. And now from CBS News in Washington, Bob Schieffer. SCHIEFFER: Good morning again. With us in the studio, Senator Kerry, and welcome back to the... Senator JOHN KERRY (Democrat, Massachusetts): Good morning. SCHIEFFER: ...Sunday talk show circuit. This is your first Sunday appearance... Sen. KERRY: Glad to be here. SCHIEFFER: ...I believe, since January, our first face-to-face interview since... Sen. KERRY: Happy to be with you. -

Congressional Record—Senate S8251

December 20, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S8251 is absolutely right—you did not seek Gyongyosi, a member of the notorious Court have ruled against the mass dis- the headlines on that legislation, but it extremist party Jobbik and also vice missal of judges in Hungary’s court- could not have been done without your chairman of the Parliament’s Foreign packing scheme, there is still no rem- direction and your help. Affairs Committee, suggested that edy for any of the dismissed judges? I just want to thank you for what Hungarian Jews are a threat to Hun- What is the status of media freedom you have done to advance the reputa- gary’s national security and those in in Hungary, let alone the fight against tion of the Senate and public service, government and Parliament should be anti-Semitism, if a journalist who standing by your convictions, yet registered. The ink was barely dry on writes about anti-Semitism faces pos- doing so in a way that we could work letters protesting those comments sible sanction before the courts for together, respecting everyone’s right when another Hungarian member of doing so? to be heard and our right to work to- Parliament, Balazs Lenhardt, partici- What are we to make of Hungary’s gether. You are indeed a model Sen- pated in a public demonstration last new election framework, which in- ator, and it has been an honor to serve week where he burned an Israeli flag. cludes many troubling provisions, in- with you in the Senate. The fact is that these are only the cluding a prohibition on campaign ads The PRESIDING OFFICER. -

The Choice of Running Mate

CBS NEWS POLL For release: Wednesday August 6, 2008 7:00 A.M. VICE PRESIDENTIAL CHOICES July 31 - August 5, 2008 By over two to one, voters say that a candidate’s choice of a running mate won’t matter much when deciding which candidate to support for president. 67% say they will be voting based mostly on the presidential candidates, not on whom those men choose as their vice presidential nominee. But 30% say that the choice of a running mate will have a great deal of influence on their vote -- twice the number who said it would matter in July 2000, before George W. Bush and Al Gore made their choices. RUNNING MATE CHOICE (Among registered voters) Now 7/2000 A great deal of influence on vote 30% 15% Vote based on presidential candidates 67 81 Voters who are still undecided are more apt than those currently favoring Obama or McCain to say the candidates’ choices for vice president will be important to their vote -- 48% say it will influence their vote, 47% say it won’t. Independents (35%) are more likely than Democrats (30%) or Republicans (24%) to say the choice of vice presidential nominee will matter. Moderates are also more likely to say it will influence their vote. RUNNING MATE CHOICE (Among registered voters) Reps Dems Inds A great deal of influence on vote 24% 30% 35% Vote based on presidential candidates 74 68 60 Once the vice presidential nominees are announced, more voters are likely to decide those choices are important, if history is any guide. -

Remarks at a Brunch for Hillary Clinton in Philadelphia

Administration of William J. Clinton, 2000 / Sept. 17 2117 country, never had an African-American where, in the deep and lost threads of my judge. Last year I told you I nominated James own memory, are the roots of understanding Wynn, a distinguished judge from North of what you have known. Somewhere, there Carolina. After 400 days, with his senior Sen- was a deep longing to share the fate of the ator still standing in the courthouse door, the people who had been left out and left behind, Senate hasn't found one day to give Judge sometimes brutalized, and too often ignored Wynn even a hearing. or forgotten. This year I nominated Roger Gregory of I don't exactly know who all I have to thank Virginia, the first man in his family to finish for that. But I'm quite sure I don't deserve high school, a teacher at Virginia State Uni- any credit for it, because whatever I did, I versity, where his mother once worked as a really felt I had no other choice. maid, a highly respected litigator with the I want you to remember that I had a part- support of his Republican and his Demo- ner that felt the same way, that I believe he cratic Senator from Virginia. But so far, we're will be one of the great Presidents this coun- still waiting for him to get a hearing. And try ever had, and that for the rest of my days, then there's Kathleen McCree Lewis in no matter whatÐno matter whatÐI will al- Michigan and others all across this country. -

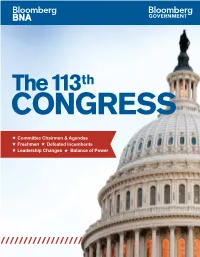

SENATE HOUSE Lydia Beyoud, Cheryl Bolen, Heather Caygle, Kenneth P

Staff and Credits TABLE of CONTENTS Obama Elected to a Second Term, Facing Fiscal Cliff and Nation Divided 2 PAUL ALBERGO Status Quo House Election Outcomes Seen Unlikely to Result in Big Changes 4 Managing Editor, Daily Report for Executives Democrats Expand Majority Status but Contentiousness Looms in January 5 CHERYL SAENZ, MICHAEL R. TRIPLETT Membership Changes to the 113th 8 Assistant Managing Editors, Daily Report for Executives 113th Congress by the Numbers 52 REPORTERS Alexei Alexis, Paul Barbagallo, Alison Bennett, SENATE HOUSE Lydia Beyoud, Cheryl Bolen, Heather Caygle, Kenneth P. Doyle, Brett Ferguson, Diane Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry 12 Admininistration 31 Freda, Lynn Garner, Diana I. Gregg, Marc Appropriations 13 Agriculture 32 Heller, Aaron E. Lorenzo, Jonathan Nicholson, Nancy Ognanovich, Heather M. Rothman, Armed Services 15 Appropriations 33 Denise Ryan, Robert T. Zung Banking, Housing & Urban Affairs 16 Armed Services 35 EDITORS Budget 18 Budget 36 Sean Barry, Theresa A. Barry, Jane Bowling, Sue Doyle, Kathie Felix, Steve France, Commerce, Science & Transportation 18 Education & the Workforce 37 Dave Harrison, John Kirkland, Vandana Energy & Natural Resources 20 Energy & Commerce 38 Mathur, Ellen McCleskey, Isabella Perelman, Karen Saunders Environment & Public Works 22 Ethics 40 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Ethics 23 Financial Services 41 Susan Raleigh Jenkins, Jeff Kinney, Susan J. McGolrick, John Sullivan, Joe Tinkelman Finance 26 Foreign Affairs 43 MIKE WRIGHT Foreign Relations 25 Homeland Security 44 Production Control