Malatesta in Brexitland: Toward Post-Statist Geographies of Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

The Italians and the Iwma

chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. This chapter will also include some brief words on the sociology and geography of Italian Internationalism and a discussion of newer approaches that transcend the rather stale polemics between parti- sans of a Marxist or anarchist reading of Italian Internationalism and incorpo- rates themes that have enlivened the study of the Risorgimento, namely, State responses to the International, the role of transnationalism, romanticism, 1 The best overviews of the iwma in Italy are: Pier Carlo Masini, La Federazione Italiana dell’Associazione Internazionale dei Lavoratori. Atti ufficiali 1871–1880 (atti congressuali; indirizzi, proclaim, manifesti) (Milan, 1966); Pier Carlo Masini, Storia degli Anarchici Ital- iani da Bakunin a Malatesta, (Milan, (1969) 1974); Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism 1864–1892 (Princeton, 1993); Renato Zangheri, Storia del socialismo italiano. -

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Anarchist Social Science : Its Origins and Development

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Anarchist social science : its origins and development. Rochelle Ann Potak University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Potak, Rochelle Ann, "Anarchist social science : its origins and development." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2504. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2504 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANARCHIST SOCIAL SCIENCE: ITS ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis Presented By ROCHELLE ANN POTAK Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the den:ree of MASTER OF ARTS December 1974 Political Science ANARCHIST SOCIAL SCIENCE: ITS ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis By ROCHELLE AliN POTAK Approved as to style and content by: Guenther Lewy, Chairman of Committee Dean Albertson, Member — Glen Gordon, Chairman Department of Political Science December 197^ Affectionately dedicated to my friends Men have sought for aees to discover the science of govern- ment; and lo l here it is, that men cease totally to attempt to govern each other at allJ that they learn to know the consequences of their OT-m acts, and that they arrange their relations with each other upon such a basis of science that the disagreeable consequences shall be assumed by the agent himself. Stephen Pearl Andrews V PREFACE The primary purpose of this thesis is to examine anarchist thought from a new perspective. -

Squatted Social Centres in England and Italy in the Last Decades of the Twentieth Century

Squatted social centres in England and Italy in the last decades of the twentieth century. Giulio D’Errico Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of History and Welsh History Aberystwyth University 2019 Abstract This work examines the parallel developments of squatted social centres in Bristol, London, Milan and Rome in depth, covering the last two decades of the twentieth century. They are considered here as a by-product of the emergence of neo-liberalism. Too often studied in the present tense, social centres are analysed here from a diachronic point of view as context- dependent responses to evolving global stimuli. Their ‗journey through time‘ is inscribed within the different English and Italian traditions of radical politics and oppositional cultures. Social centres are thus a particularly interesting site for the development of interdependency relationships – however conflictual – between these traditions. The innovations brought forward by post-modernism and neo-liberalism are reflected in the centres‘ activities and modalities of ‗social‘ mobilisation. However, centres also voice a radical attitude towards such innovation, embodied in the concepts of autogestione and Do-it-Yourself ethics, but also through the reinstatement of a classist approach within youth politics. Comparing the structured and ambitious Italian centres to the more informal and rarefied English scene allows for commonalities and differences to stand out and enlighten each other. The individuation of common trends and reciprocal exchanges helps to smooth out the initial stark contrast between local scenes. In turn, it also allows for the identification of context- based specificities in the interpretation of local and global phenomena. -

BY ERRICO MALATESTA “Knowledge Should Be Free” ANARCHY

ANARCHY Insurgency Culture Collective BY ERRICO MALATESTA “Knowledge Should Be Free” ANARCHY The government takes charge, for instance, of the postal and telegraph services. But in what way does it really assist them? When the people are in such a condition as to be able to enjoy and feel the need of such services they will think about organizing them, and the man with the necessary technical knowledge will not require a certificate from a government to enable him to set to work. The more general and urgent the need, the more volunteers will offer to satisfy it. Would the people have the ability necessary to provide and distribute provisions? Never fear, they will not die of hunger waiting for government to pass a law on the subject. Wherever a government exists, it must wait until the people have first organized everything, and then come with its laws to sanction and exploit what has ANARCHY already been done. It is evident that private interest is the great motive for all activity. That being so, when the interest of every one becomes the interest of each (and it necessarily will become so as soon as private [ l'Anarchia ] property is abolished), then all will be active. If they work now in the interest of the few, so much more and so much better will they work to satisfy the interests of all. It is hard to understand how anyone can believe that public services indispensable to social life can be better secured by order of a government than through the workers themselves who by their own choice or by agreement with others carry them out under the immediate control of all those interested. -

Toward Anarchy: a Historical Sketch of the Anarchism-Democracy Divide

Theory in Action, Vol. 13, No. 1, January (© 2020) DOI:10.3798/tia.1937-0237.2004 Toward Anarchy: A Historical Sketch of the Anarchism-Democracy Divide Markus Lundström1 This article traces divergent approaches to democracy in the history of anarchist thought. It outlines an anarchist critique of democracy, a defiant composition arrayed against authority, representation and majority rule. Put in contrast to that approach is the anarchist reclamation, the understanding of anarchy as democracy radicalized. The article shows how the critique of democracy typifies classical anarchist thought, while reclamation of democracy breeds in post- classical anarchism after 1939. Yet these lines of thought also coexist historically, and they both continue into our days. Anarchism is now depicted in terms of radical democracy, while a reclaimed critique once again dissociates anarchy from democracy. In an attempt to recognize dialogue between them, this article suggests that divergent approaches articulate an impossible argument that could further the route toward anarchy. [Article copies available for a fee from The Transformative Studies Institute. E-mail address: [email protected] Website: http://www.transformativestudies.org ©2020 by The Transformative Studies Institute. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS: Anarchism, Democracy, Suffrage, Errico Malatesta, Emma Goldman. ANARCHISM-DEMOCRACY IN RETROSPECT In the crooked history of anarchist ideas and actions, approaches to democracy have indeed been variegated, diverse, and discontinuous. Clearly the anarchist tradition nurtures an emblematic resistance to governance. Democracy, however, could be understood – and have so been, even by anarchists – as a promising effort in an egalitarian, participatory vein. Radical-democratic scholars typically construe democracy as agonistic rather than antagonistic (Mouffe 2013), a lively process rather than a permanent state (Rancière 2006), an 1 Markus Lundström, Ph.D., Stockholm University, Sweden. -

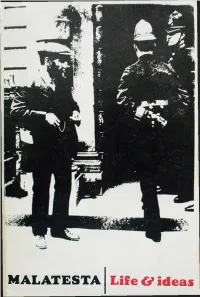

MALATESTA His Life Ideas

M ALATESTA Life & id eas ERRICO MALATESTA His Life Ideas Compiled and Edited by VERNON RICHARDS m m i i ® 2 9 3 4 Ri/E ST-URSAiH, MONTREAL 131 T*L 15145 844-4076 LONDON FREEDOM PRESS 1965 First Published 1965 by FREEDOM PRESS 17a Maxwell Road, London, S.W.6 Printed by Express Printers London, E.l Printed in Gi. Britain To the memory of Camillo and Giovanna Berneri and their daughter Marie-Louise Berneri CONTENTS Editor’s Foreword PaSe 9 P a r t O n e Introduction: Anarchism and Anarchy 19 I 1 Anarchist Schools of Thought 29 2 Anarchist-Communism 34 3 Anarchism and Science 38 4 Anarchism and Freedom 47 5 Anarchism and Violence 53 6 Attentats 61 it 7 Ends and Means 68 8 Majorities and Minorities 72 9 Mutual Aid 93 10 Reformism 98 11 Organisation 83 in 12 Production and Distribution 91 13 The Land 97 14 Money and Banks 100 15 Property 102 16 Crime and Punishment 105 IV 17 Anarchists and the Working Class Movements 113 18 The Occupation of the Factories 134 19 Workers and Intellectuals 137 20 Anarchism, Socialism and Communism 141 21 Anarchists and the Limits of Political Co-Existence 148 v 22 The Anarchist Revolution 153 23 The Insurrection 163 24 Expropriation 167 25 Defence of the Revolution 170 VI 26 Anarchist Propaganda 177 27 An Anarchist Programme 182 P a r t Two Notes for a Biography (V.R.) 201 Source Notes 241 A PPEN D IC ES I Anarchists have forgotten their Principles (E.M. -

What Did You Do in the Drug War, Daddy?

7 Colin Craig What did you do in the Drug War, Daddy? Inhaling metaphor The War on Drugs has been going on since US President Richard Nixon coined the term in the late 1960s. It appears at first sight to be a completely illogical concept: how, we might ask ourselves, can a war be fought against a conceptual term that defies definition? Of course, the War on Drugs refers to those drugs that have been proscribed by law and therefore deemed illegal, and it represents a conflict with the express intention of eradicating illicit substance use from the face of the planet. In actual fact, since the outset of the War on Drugs, there has been both a proliferation of drug use across the whole world and an enormous growth in the numbers of consumers. Former Eastern Bloc nations where drug use was previously virtually unknown now have huge burgeoning drug markets fuelled by the breakdown of borders, the growth in trade and ultimately by mass populations with a desire to seek out new forms of oblivion. Wars of metaphor are an important element in modern political culture and the War on Drugs and the War on Terror are the latest in a long line, which most famously included the War on Poverty in the United States of the 1960s (Piven and Cloward, 1977). For the purposes of this argument it is important to see the War on Drugs and the War on Terror as crucially interlinked. The use of these particular metaphors has enabled the same secretive governing forces to extend conflicts across international boundaries without declaring war in a conven- tional sense. -

Errico Malatesta

Enrico Tuccinardi, Salvatore Mazzariello. Architettura di una chimera. Mantova: Universitas Studiorum, 2014. 184 pp. EUR 16.00, cloth, ISBN 978-88-97683-72-8. Reviewed by Kenyon Zimmer Published on H-Italy (March, 2018) Commissioned by Matteo Pretelli (University of Naples "L'Orientale") In this remarkably well-researched and looked documents in French and Spanish, and provocative book, authors Enrico Tuccinardi and they include transcriptions of many of these—ei‐ Salvatore Mazzariello use a letter intercepted by ther in excerpted form or in their entirety—with‐ Italian authorities in May, 1901, to uncover a clan‐ in the book’s seven chapters and appendix. This destine transnational world populated by revolu‐ meticulous research brings to light a loose-knit, tionary plots, a deposed queen, and police spies transnational radical network that included not and government officials dedicated to foiling only anarchists, but sympathetic socialists and these unlikely allies’ efforts. It is an outstanding less easily definable individuals like Angelo In‐ model of historical research and methodology sogna, a onetime anarchist turned Bourbon that deserves attention from scholars outside of restorationist and confidant of the deposed Queen the felds of Italian and radical history. However, of the Two Sicilies, Maria Sofia. The authors also it ultimately fails to substantiate its most sensa‐ reveal the international web of informants, police tional argument. spies, and political operatives dedicated to The document around which the study is or‐ surveilling and disrupting these subversive ganized was penned in May of 1901 by famed Ital‐ threats. ian anarchist Errico Malatesta, then residing in At the center of the book’s argument is a pe‐ exile in London, and addressed to a heretofore culiar episode, long known to specialists in the unknown companion in Paris.