The Challenge of Establishing a Personalised Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prescription Pattern of Primary Osteoarthritis in Tertiary Medical

Published online: 2020-04-21 Running title: Primary Osteoarthritis Nitte University Journal of Health Science Original Article Prescription Pattern of Primary Osteoarthritis in Tertiary Medical Centre Sowmya Sham Kanneppady1, Sham Kishor Kanneppady2, Vijaya Raghavan3, Aung Myo Oo4, Ohn Mar Lwin5 1Senior Lecturer and Head, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Lincoln University College, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia, 2Senior Lecturer, School of Dentistry, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3Head of the Department of Pharmacology, KVG Medical College and Hospital, Kurunjibag, Sullia, Karnataka, India. 4Assistant Professor, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Lincoln University College, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia, 5Post graduate student, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. *Corresponding Author : Sowmya Sham Kanneppady, Senior Lecturer and Head,Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Lincoln University College, No. 2, Jalan Stadium, SS 7/15, Kelana Jaya, 47301, Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. E-mail : [email protected]. Received : 12.10.2017 Abstract Review Completed : 05.12.2017 Objectives: Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the commonest joint/musculoskeletal disorders, Accepted : 06.12.2017 affecting the middle aged and elderly, although younger people may be affected as a result of injury or overuse. The study aimed to analyze the data, evaluate the prescription pattern and Keywords: Osteoarthritis, anti- rationality of the use of drugs in the treatment of primary OA with due emphasis on the inflammatory agents, prevalence available treatment regimens. Materials and methods: Medical case records of patients suffering from primary OA attending Access this article online the department of Orthopedics of a tertiary medical centre were the source of data. -

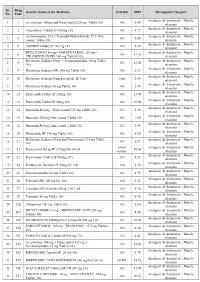

PMBJP Product.Pdf

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

Guideline for the Management of Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis Second Edition

Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis Second edition racgp.org.au Healthy Profession. Healthy Australia. Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Second edition Disclaimer The information set out in this publication is current at the date of first publication and is intended for use as a guide of a general nature only and may or may not be relevant to particular patients or circumstances. Nor is this publication exhaustive of the subject matter. Persons implementing any recommendations contained in this publication must exercise their own independent skill or judgement or seek appropriate professional advice relevant to their own particular circumstances when so doing. Compliance with any recommendations cannot of itself guarantee discharge of the duty of care owed to patients and others coming into contact with the health professional and the premises from which the health professional operates. Whilst the text is directed to health professionals possessing appropriate qualifications and skills in ascertaining and discharging their professional (including legal) duties, it is not to be regarded as clinical advice and, in particular, is no substitute for a full examination and consideration of medical history in reaching a diagnosis and treatment based on accepted clinical practices. Accordingly, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Ltd (RACGP) and its employees and agents shall have no liability (including without limitation liability by reason of negligence) to any users of the information contained in this publication for any loss or damage (consequential or otherwise), cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information contained in this publication and whether caused by reason of any error, negligent act, omission or misrepresentation in the information. -

Efficacy and Safety of Diacerein And

2012 iMedPub Journals Vol. 1 No. 1:5 Our Site: http://www.imedpub.com/ JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES doi: 10.3823/1004 Effi cacy and safety Navin Gupta2*, Somnath Datta1 of diacerein and 1 Assistant Professor 2 Marketing Lead, Bristol Correspondence: Department of Pharmacology, Mayers Squibb, Lower Parel, diclofenac in knee FOD, Jamia Millia Islamia, Mumbai * Department of Pharmacology, New Delhi Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia osteoarthritis in Millia Islamia, New Delhi1 Indian patients- Mobile: +91-9873150172 drgargmedico2002@ a prospective yahoo.co.in randomized open Running head: Diacerein versus diclofenac effects in patients of knee osteoar- label study thritis. Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Diacerein, Diclofenac, Visual analog scale, Western On- tario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index, Lequesne impairment index What is already known about this subject: Diclofenac is a well- known NSAID used in the management of pain in Osteoarthritis(OA). Diacerein is a slow acting, disease-modifying drug approved for OA. What this study adds: Diclofenac, diacerein as well as combination of the two improved the quality of life as compared to baseline. Diacerein has acceptable toxicity and long carry-over effect in osteoarthritis patients. Abstract Objectives: To determine the effi cacy and carryover effects of diacerein vs diclof- enac in Indian population with knee osteoarthritis (OA). Study design: After one week NSAID’s washout period, patients received either diacerein or diclofenac or combination for 12 weeks with 4 weeks follow-up to determine the carryover effects of the drugs. The primary effi cacy end point was the change from baseline in 100mm visual analog scale (VAS) score after 20 meters walk. -

Efficacy and Safety of Diacerein in Patients with Inadequately

1356 Diabetes Care Volume 40, October 2017 Efficacy and Safety of Diacerein Claudia R.L. Cardoso, Nathalie C. Leite, Fernanda O. Carlos, Andreia´ A. Loureiro, in Patients With Inadequately Bianca B. Viegas, and Gil F. Salles Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial Diabetes Care 2017;40:1356–1363 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-0374 OBJECTIVE To assess, in a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy and safety of diacerein, an immune modulator anti-inflammatory drug, in improving glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS Eighty-four patients with HbA1c between 7.5 and 9.5% (58–80 mmol/mol) were randomized to 48-week treatment with placebo (n = 41) or diacerein 100 mg/day (n = 43). The primary outcome was the difference in mean HbA1c changes during treatment. Secondary outcomes were other efficacy and safety measurements. A gen- eral linear regression with repeated measures, adjusted for age, sex, diabetes duration, and each baseline value, was used to estimate differences in mean changes. Both intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and per-protocol analysis (excluding 10 patients who interrupted treatment) were performed. RESULTS Diacerein reduced HbA1c compared with placebo by 0.35% (3.8 mmol/mol; P =0.038) EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES AND THERAPEUTICS in the ITT analysis and by 0.41% (4.5 mmol/mol; P = 0.023) in the per-protocol analysis. The peak of effect occurred at the 24th week of treatment (20.61% [6.7 mmol/mol; P =0.014]and20.78% [8.5 mmol/mol; P = 0.005], respectively), but it attenuated fi fi toward nonsigni cant differences at the 48th week. -

Diacerein Vis-À-Vis Etoricoxib for Osteoarthritis of Knee

International Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Sciences ISSN: 2277-2103 (Online) An Open Access, Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/jms.htm 2015 Vol. 5 (2) May-August, pp. 116-122/Chaudhary et al. Research Article DIACEREIN VIS-À-VIS ETORICOXIB FOR OSTEOARTHRITIS OF KNEE: RESULTS OF A QUASI EXPERIMENTAL STUDY *Chaudhary P.1, Shivalli2 S., Jaybhaye1 D., Deshmukh3 S., Saraf S.4 and Pandey B.5 1Department of Pharmacology, MGM Medical College and Hospital, Aurangabad, Maharashtra 2Department of Community Medicine, Yenepoya Medical College, Yenepoya University, Manglore, Karnataka 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Govt Medical College,Aurangabad, Maharashtra 4Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP 5Department of Orthopedics, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP *Author for Correspondence ABSTRACT Osteoarthritis represents prime disability burdening the society. Therapy is largely symptomatic with NSAIDs which pose risk in the elderly. Supplement cartilage ingredients are sometimes employed with no consensus. Diacerein and its active metabolite rhein inhibit the synthesis of IL-1in human OA synovium in vitro as well as the expression of IL-1 receptors on chondrocytes. Present observational study in 91 cases attempts to examine therapeutic outcome with Diacerein, a disease modifying drug in comparison with standard etoricoxib therapy in cases of knee osteoarthritis. 100 mg daily dose of Diacerein for 3 months was studied for clinical benefit on KOOS score measures in 50 cases with radiological grade I, II and III osteoarthritis. 41 cases treated with etoricoxib90 mg OD were the group for comparison. Diacerein therapy markedly benefited in overall improvement of KOOS score highly significantly as also the symptoms scores as well as in stiffness as compared to etoricoxib. -

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of - Medicines belonging to the ATC group M01 (Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 6 DISCLAIMER 8 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 9 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Phenylbutazone (ATC: M01AA01) 11 Mofebutazone (ATC: M01AA02) 17 Oxyphenbutazone (ATC: M01AA03) 18 Clofezone (ATC: M01AA05) 19 Kebuzone (ATC: M01AA06) 20 Indometacin (ATC: M01AB01) 21 Sulindac (ATC: M01AB02) 25 Tolmetin (ATC: M01AB03) 30 Zomepirac (ATC: M01AB04) 33 Diclofenac (ATC: M01AB05) 34 Alclofenac (ATC: M01AB06) 39 Bumadizone (ATC: M01AB07) 40 Etodolac (ATC: M01AB08) 41 Lonazolac (ATC: M01AB09) 45 Fentiazac (ATC: M01AB10) 46 Acemetacin (ATC: M01AB11) 48 Difenpiramide (ATC: M01AB12) 53 Oxametacin (ATC: M01AB13) 54 Proglumetacin (ATC: M01AB14) 55 Ketorolac (ATC: M01AB15) 57 Aceclofenac (ATC: M01AB16) 63 Bufexamac (ATC: M01AB17) 67 2 Indometacin, Combinations (ATC: M01AB51) 68 Diclofenac, Combinations (ATC: M01AB55) 69 Piroxicam (ATC: M01AC01) 73 Tenoxicam (ATC: M01AC02) 77 Droxicam (ATC: M01AC04) 82 Lornoxicam (ATC: M01AC05) 83 Meloxicam (ATC: M01AC06) 87 Meloxicam, Combinations (ATC: M01AC56) 91 Ibuprofen (ATC: M01AE01) 92 Naproxen (ATC: M01AE02) 98 Ketoprofen (ATC: M01AE03) 104 Fenoprofen (ATC: M01AE04) 109 Fenbufen (ATC: M01AE05) 112 Benoxaprofen (ATC: M01AE06) 113 Suprofen (ATC: M01AE07) 114 Pirprofen (ATC: M01AE08) 115 Flurbiprofen (ATC: M01AE09) 116 Indoprofen (ATC: M01AE10) 120 Tiaprofenic Acid (ATC: -

EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis

936 Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59:936–944 Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.59.12.936 on 1 December 2000. Downloaded from EXTENDED REPORTS EULAR recommendations for the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT) A Pendleton, N Arden, M Dougados, M Doherty, B Bannwarth, J W J Bijlsma, F Cluzeau, C Cooper, P A Dieppe, K-P Günther, H J Hauselmann, G Herrero-Beaumont, P M Kaklamanis, B Leeb, M Lequesne, S Lohmander, B Mazieres, E-M Mola, K Pavelka, U Serni, B Swoboda, A A Verbruggen, G Weseloh, I Zimmermann-Gorska Abstract Osteoarthritis (OA) is by far the most common disease to Background—Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most com- aVect synovial joints. It is a major cause of musculoskeletal mon joint disease encountered throughout Europe. A pain, the single most important cause of disability and task force for the EULAR Standing Committee for handicap from arthritis, and an important community Clinical Trials met in 1998 to determine the healthcare burden. OA is strongly associated with aging methodological and logistical approach required for and, with the increasing proportion of elderly in Western the development of evidence based guidelines for populations, large joint OA, particularly of the knee, will treatment of knee OA. The guidelines were restricted become an even more important healthcare challenge. to cover all currently available treatments for knee Multiple genetic, constitutional, and environmental fac- OA diagnosed either clinically and/or radiographi- tors may contribute to the development and variable cally aVecting any compartment of the knee. -

Safety of Symptomatic Slow-Acting Drugs for Osteoarthritis

Drugs & Aging (2019) 36 (Suppl 1):S65–S99 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00662-z SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Safety of Symptomatic Slow‑Acting Drugs for Osteoarthritis: Outcomes of a Systematic Review and Meta‑Analysis Germain Honvo1,2 · Jean‑Yves Reginster1,2,3 · Véronique Rabenda1,2 · Anton Geerinck1,2 · Ouafa Mkinsi4 · Alexia Charles1,2 · Rene Rizzoli2,5 · Cyrus Cooper2,6,7 · Bernard Avouac1 · Olivier Bruyère1,2 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Background Symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SYSADOAs) are an important drug class in the treatment armamentarium for osteoarthritis (OA). Objective We aimed to re-assess the safety of various SYSADOAs in a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized placebo- controlled trials, using, as much as possible, data from full safety reports. Methods We performed a systematic review and random-efects meta-analyses of randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled trials that assessed adverse events (AEs) with various SYSADOAs in patients with OA. The databases MED- LINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Ovid CENTRAL) and Scopus were searched. The primary outcomes were overall severe and serious AEs, as well as AEs involving the following Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) system organ classes (SOCs): gastrointestinal, cardiac, vascular, nervous system, skin and subcutaneous tissue, musculoskeletal and connective tissue, renal and urinary system. Results Database searches initially identifed 3815 records. After exclusions according to the selection criteria, 25 stud- ies on various SYSADOAs were included in the qualitative synthesis, and 13 studies with adequate data were included in the meta-analyses. Next, from the studies previously excluded according to the protocol, 37 with mainly oral nonsteroidal anti-infammatory drugs (NSAIDs) permitted as concomitant medication were included in a parallel qualitative synthesis, from which 18 studies on various SYSADOAs were included in parallel meta-analyses. -

Benefit–Risk Assessment of Diacerein in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis

Drug Saf DOI 10.1007/s40264-015-0266-z REVIEW ARTICLE Benefit–Risk Assessment of Diacerein in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis Elena Panova • Graeme Jones Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 Abstract Osteoarthritis (OA) is the leading muscu- loskeletal cause of disability. Despite this, there is no Key Points consensus on the precise definition of OA and what is the best treatment to improve symptoms and slow disease There are limited therapeutic options for progression. Current pharmacological treatments include osteoarthritis, and interleukin-1, which is blocked by analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs diacerein, is one potential target. (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors. None of those treatments are disease-modifying agents that target Clinical trials show that diacerein has a modest the core pathological processes in OA. Diacerein, a semi- symptomatic benefit, with a controversial effect on synthetic anthraquinone derivative, inhibits the interleukin- radiographs in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis. 1-beta (IL-1b) cytokine which, according to animal studies, plays a key role in the pathogenesis of OA. Diacerein was Overall, diacerein is safe, apart from a substantially synthesized in 1980 and licensed in some European Union higher risk of diarrhoea, especially with longer-term and Asian countries for up to 20 years. It has shown use. modest efficacy and acceptable tolerability in a number of trials of low to moderate quality. Early this year, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) conducted a review and restricted the use of diacerein-containing medicines. This was because of major concerns about the frequency 1 Introduction and severity of diarrhoea and liver disorders in OA pa- tients. -

Randomized Controlled Studies on the Efficacy of Antiarthritic Agents In

TenBroek et al. Arthritis Research & Therapy (2016) 18:24 DOI 10.1186/s13075-016-0921-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Randomized controlled studies on the efficacy of antiarthritic agents in inhibiting cartilage degeneration and pain associated with progression of osteoarthritis in the rat Erica M. TenBroek1*, Laurie Yunker1, Mae Foster Nies1 and Alison M. Bendele2 Abstract Background: As an initial step in the development of a local therapeutic to treat osteoarthritis (OA), a number of agents were tested for their ability to block activation of inflammation through nuclear factor κ-light-chain- enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), subchondral bone changes through receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL)-mediated osteoclastogenesis, and proteolytic degradation through matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 activity. Candidates with low toxicity and predicted efficacy were further examined using either of two widely accepted models of OA joint degeneration in the rat: the monoiodoacetic acid (MIA) model or the medial meniscal tear/medial collateral ligament tear (MMT/MCLT) model. Methods: Potential therapeutics were assessed for their effects on the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis, and MMP-13 activity in vitro using previously established assays. Toxicity was measured using HeLa cells, a synovial cell line, or primary human chondrocytes. Drugs predicted to perform well in vivo were tested either systemically or via intraarticular injection in the MIA or the MMT/MCLT model of OA. Pain behavior was measured by mechanical hyperalgesia using the digital Randall-Selitto test (dRS) or by incapacitance with weight bearing (WB). Joint degeneration was evaluated using micro computed tomography and a comprehensive semiquantitative scoring of cartilage, subchondral bone, and synovial histopathology. -

Solubility Enhancement of Diacerein by Mannitol Solid Dispersons

International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Academic Sciences ISSN- 0975-1491 Vol 3, Issue 4, 2011 Research Article SOLUBILITY ENHANCEMENT OF DIACEREIN BY MANNITOL SOLID DISPERSONS PRASHANT S.WALKE*1, PRASHANT S.KHAIRNAR1, M.R.NARKHEDE 1, J.Y.NEHETE1 1Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, MGV’s Pharmacy College, Panchavati, Nashik - 422 003, Maharashtra, India. Email: [email protected] Received: 3 July 2011, Revised and Accepted: 10 Aug 2011 ABSTRACT Bioavailability can be increased by changing the disintegration and dissolution rate. The aqueous solubility of drugs lesser than 1µg /ml will create a bioavailability problem and thereby affecting the efficacy of the drug. There are numerous reported methods to enhance aqueous solubility of poorly soluble drug among them solid dispersions is one of the effective and accepted technique in the pharmaceutical industry. Therefore in this study attempt is done to improve the physicochemical properties of diacerein, a poorly water soluble drug, by forming dispersion with mannitol as water soluble carrier. The solid dispersions of Diacerein were prepared in ratio 1:1, 1:3 and 1:5 by physical triturating, solvent evaporation and fusion method. The results revealed that dispersions showed marked increase in the saturation solubility and dissolution rate of Diacerein as compaired to pure drug. A mannitol dispersion (1:5) prepared by fusion method showed faster dissolution rate among studied solid dispersion. The FT‐IR shows the complexation and there were hydrogen bonding interactions.Solid dispersions also characterized by using DSC and PXRD. Finally, solid dispersions of Diacerein: mannitol prepared as 1:5 ratio by fusion method showed excellent physicochemical characteristics and was found to be described by dissolution kinetics and was selected as the best formulation in the study.The release study findings were well supported by the results of wettability, saturation solubility and permeability studies.