2010 AAOMPT Krista Clark Natural Alternatives to Long-Term NSAID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suitability of Immobilized Systems for Microbiological Degradation of Endocrine Disrupting Compounds

molecules Review Suitability of Immobilized Systems for Microbiological Degradation of Endocrine Disrupting Compounds Danuta Wojcieszy ´nska , Ariel Marchlewicz and Urszula Guzik * Institute of Biology, Biotechnology and Environmental Protection, Faculty of Natural Science, University of Silesia in Katowice, Jagiello´nska28, 40-032 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (A.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-3220-095-67 Academic Editors: Urszula Guzik and Danuta Wojcieszy´nska Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 25 September 2020; Published: 29 September 2020 Abstract: The rising pollution of the environment with endocrine disrupting compounds has increased interest in searching for new, effective bioremediation methods. Particular attention is paid to the search for microorganisms with high degradation potential and the possibility of their use in the degradation of endocrine disrupting compounds. Increasingly, immobilized microorganisms or enzymes are used in biodegradation systems. This review presents the main sources of endocrine disrupting compounds and identifies the risks associated with their presence in the environment. The main pathways of degradation of these compounds by microorganisms are also presented. The last part is devoted to an overview of the immobilization methods used for the purposes of enabling the use of biocatalysts in environmental bioremediation. Keywords: EDCs; hormones; degradation; immobilization; microorganisms 1. Introduction The development of modern tools for the separation and identification of chemical substances has drawn attention to the so-called micropollution of the environment. Many of these contaminants belong to the emergent pollutants class. According to the Stockholm Convention they are characterized by high persistence, are transported over long distances in the environment through water, accumulate in the tissue of living organisms and can adversely affect them [1]. -

SPIRONOLACTONE Spironolactone – Oral (Common Brand Name

SPIRONOLACTONE Spironolactone – oral (common brand name: Aldactone) Uses: Spironolactone is used to treat high blood pressure. Lowering high blood pressure helps prevent strokes, heart attacks, and kidney problems. It is also used to treat swelling (edema) caused by certain conditions (e.g., congestive heart failure) by removing excess fluid and improving symptoms such as breathing problems. This medication is also used to treat low potassium levels and conditions in which the body is making too much of a natural chemical (aldosterone). Spironolactone is known as a “water pill” (potassium-sparing diuretic). Other uses: This medication has also been used to treat acne in women, female pattern hair loss, and excessive hair growth (hirsutism), especially in women with polycystic ovary disease. Side effects: Drowsiness, lightheadedness, stomach upset, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or headache may occur. To minimize lightheadedness, get up slowly when rising from a seated or lying position. If any of these effects persist or worsen, notify your doctor promptly. Tell your doctor immediately if any of these unlikely but serious side effects occur; dizziness, increased thirst, change in the amount of urine, mental/mood chances, unusual fatigue/weakness, muscle spasms, menstrual period changes, sexual function problems. This medication may lead to high levels of potassium, especially in patients with kidney problems. If not treated, very high potassium levels can be fatal. Tell your doctor immediately if you notice any of the following unlikely but serious side effects: slow/irregular heartbeat, muscle weakness. Precautions: Before taking spironolactone, tell your doctor or pharmacist if you are allergic to it; or if you have any other allergies. -

Meloxicam 15 Mg Orodispersible Tablets Meloxicam 15.0 Mg

PACKAGE LEAFLET: INFORMATION FOR THE USER Meloxicam 15 mg Orodispersible Tablets Meloxicam 15.0 mg Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking may occur if you have serious blood loss or burns, surgery or low this medicine. fluid intake; Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. if you have ever been diagnosed with high potassium levels in If you have any further questions, please ask your doctor or the blood; pharmacist. Tell your doctor if you think any of these apply to you. This medicine has been prescribed for you. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their symptoms are Warning the same as yours. Medicines such as these Meloxicam tablets may be If any of the side effects become serious, or if you notice associated with a small increased risk of heart attack or any side effects not listed in this leaflet, please tell your doctor or stroke. Any risk is more likely with high doses and prolonged pharmacist. treatment. Do not exceed the recommended dose or duration of treatment. IN THIS LEAFLET: Discuss your treatment with your doctor or pharmacist if you have heart problems, have previously had a stroke or you think you 1. What Meloxicam orodispersible tablets are and what might be at risk of conditions such as high blood pressure, they are used for diabetes or high cholesterol, or if you are a smoker. 2 . Before you take Meloxicam tablets 3. How to take Meloxicam tablets Taking other medicines When you are taking Meloxicam tablets, do not take any other 4. -

Prescription Pattern of Primary Osteoarthritis in Tertiary Medical

Published online: 2020-04-21 Running title: Primary Osteoarthritis Nitte University Journal of Health Science Original Article Prescription Pattern of Primary Osteoarthritis in Tertiary Medical Centre Sowmya Sham Kanneppady1, Sham Kishor Kanneppady2, Vijaya Raghavan3, Aung Myo Oo4, Ohn Mar Lwin5 1Senior Lecturer and Head, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Lincoln University College, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia, 2Senior Lecturer, School of Dentistry, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3Head of the Department of Pharmacology, KVG Medical College and Hospital, Kurunjibag, Sullia, Karnataka, India. 4Assistant Professor, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Lincoln University College, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia, 5Post graduate student, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. *Corresponding Author : Sowmya Sham Kanneppady, Senior Lecturer and Head,Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Lincoln University College, No. 2, Jalan Stadium, SS 7/15, Kelana Jaya, 47301, Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. E-mail : [email protected]. Received : 12.10.2017 Abstract Review Completed : 05.12.2017 Objectives: Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the commonest joint/musculoskeletal disorders, Accepted : 06.12.2017 affecting the middle aged and elderly, although younger people may be affected as a result of injury or overuse. The study aimed to analyze the data, evaluate the prescription pattern and Keywords: Osteoarthritis, anti- rationality of the use of drugs in the treatment of primary OA with due emphasis on the inflammatory agents, prevalence available treatment regimens. Materials and methods: Medical case records of patients suffering from primary OA attending Access this article online the department of Orthopedics of a tertiary medical centre were the source of data. -

Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals Carlotta Cocchetti 1, Jiska Ristori 1, Alessia Romani 1, Mario Maggi 2 and Alessandra Daphne Fisher 1,* 1 Andrology, Women’s Endocrinology and Gender Incongruence Unit, Florence University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (C.C); jiska.ristori@unifi.it (J.R.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Department of Experimental, Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, Careggi University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected]fi.it * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 26 May 2020 Abstract: Introduction: To date no standardized hormonal treatment protocols for non-binary transgender individuals have been described in the literature and there is a lack of data regarding their efficacy and safety. Objectives: To suggest possible treatment strategies for non-binary transgender individuals with non-standardized requests and to emphasize the importance of a personalized clinical approach. Methods: A narrative review of pertinent literature on gender-affirming hormonal treatment in transgender persons was performed using PubMed. Results: New hormonal treatment regimens outside those reported in current guidelines should be considered for non-binary transgender individuals, in order to improve psychological well-being and quality of life. In the present review we suggested the use of hormonal and non-hormonal compounds, which—based on their mechanism of action—could be used in these cases depending on clients’ requests. Conclusion: Requests for an individualized hormonal treatment in non-binary transgender individuals represent a future challenge for professionals managing transgender health care. For each case, clinicians should balance the benefits and risks of a personalized non-standardized treatment, actively involving the person in decisions regarding hormonal treatment. -

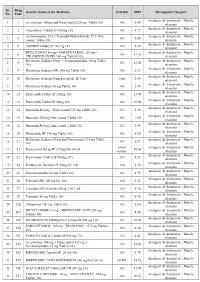

PMBJP Product.Pdf

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

Nsaids: Dare to Compare 1997

NSAIDs TheRxFiles DARE TO COMPARE Produced by the Community Drug Utilization Program, a Saskatoon District Health/St. Paul's Hospital program July 1997 funded by Saskatchewan Health. For more information check v our website www.sdh.sk.ca/RxFiles or, contact Loren Regier C/O Pharmacy Department, Saskatoon City Hospital, 701 Queen St. Saskatoon, SK S7K 0M7, Ph (306)655-8506, Fax (306)655-8804; Email [email protected] We have come a long way from the days of willow Highlights bark. Today salicylates and non-steroidal anti- • All NSAIDs have similar efficacy and side inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) comprise one of the effect profiles largest and most commonly prescribed groups of • In low risk patients, Ibuprofen and naproxen drugs worldwide.1 In Saskatchewan, over 20 may be first choice agents because they are different agents are available, accounting for more effective, well tolerated and inexpensive than 300,000 prescriptions and over $7 million in • Acetaminophen is the recommended first line sales each year (Saskatchewan Health-Drug Plan agent for osteoarthritis data 1996). Despite the wide selection, NSAIDs • are more alike than different. Although they do Misoprostol is the only approved agent for differ in chemical structure, pharmacokinetics, and prophylaxis of NSAID-induced ulcers and is to some degree pharmacodynamics, they share recommended in high risk patients if NSAIDS similar mechanisms of action, efficacy, and adverse cannot be avoided. effects. week or more to become established. For this EFFICACY reason, an adequate trial of 1-2 weeks should be NSAIDs work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) allowed before increasing the dose or changing to and subsequent prostaglandin synthesis as well as another NSAID. -

Estrogen Actions Throughout the Brain

Estrogen Actions Throughout the Brain BRUCE MCEWEN Harold and Margaret Milliken Hatch Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York 10021 ABSTRACT Besides affecting the hypothalamus and other brain areas related to reproduction, ovarian steroids have widespread effects throughout the brain, on serotonin pathways, catecholaminergic neurons, and the basal forebrain cholinergic system as well as the hippocampal formation, a brain region involved in spatial and declarative memory. Thus, ovarian steroids have measurable effects on affective state as well as cognition, with implications for dementia. Two actions are discussed in this review; both appear to involve a combination of genomic and nongenomic actions of ovarian hormones. First, regulation of the serotonergic system appears to be linked to the presence of estrogen- and progestin-sensitive neurons in the midbrain raphe as well as possibly nongenomic actions in brain areas to which serotonin neurons project their axons. Second, ovarian hormones regulate synapse turnover in the CA1 region of the hippocampus during the 4- to 5-day estrous cycle of the female rat. Formation of new excitatory synapses is induced by estradiol and involves N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, whereas downregulation of these synapses involves intracellular progestin receptors. A new, rapid method of radioimmunocytochemistry has made possible the demonstration of synapse formation by labeling and quantifying the specific synaptic and dendritic molecules involved. Although NMDA receptor activation is required for synapse formation, inhibitory interneurons may play a pivotal role as they express nuclear estrogen receptor-alpha (ER␣). It is also likely that estrogens may locally regulate events at the sites of synaptic contact in the excitatory pyramidal neurons where the synapses form. -

(Ketorolac Tromethamine Tablets) Rx Only WARNING TORADOL

TORADOL ORAL (ketorolac tromethamine tablets) Rx only WARNING TORADOLORAL (ketorolac tromethamine), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is indicated for the short-term (up to 5 days in adults), management of moderately severe acute pain that requires analgesia at the opioid level and only as continuation treatment following IV or IM dosing of ketorolac tromethamine, if necessary. The total combined duration of use of TORADOLORAL and ketorolac tromethamine should not exceed 5 days. TORADOLORAL is not indicated for use in pediatric patients and it is NOT indicated for minor or chronic painful conditions. Increasing the dose of TORADOLORAL beyond a daily maximum of 40 mg in adults will not provide better efficacy but will increase the risk of developing serious adverse events. GASTROINTESTINAL RISK Ketorolac tromethamine, including TORADOL can cause peptic ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding and/or perforation of the stomach or intestines, which can be fatal. These events can occur at any time during use and without warning symptoms. Therefore, TORADOL is CONTRAINDICATED in patients with active peptic ulcer disease, in patients with recent gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, and in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding. Elderly patients are at greater risk for serious gastrointestinal events (see WARNINGS). CARDIOVASCULAR RISK NSAIDs may cause an increased risk of serious cardiovascular thrombotic events, myocardial infarction, and stroke, which can be fatal. This risk may increase with duration of use. Patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease may be at greater risk (see WARNINGS and CLINICAL STUDIES). TORADOL is CONTRAINDICATED for the treatment of peri-operative pain in the setting of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery (see WARNINGS). -

Post Marketing Safety Data Analysis Reveals Increased Propensity For

Post Marketing Safety Data Analysis Reveals Increased Propensity for Severe Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Side Effects in Patients Taking Celecoxib Compared to Other NSAIDs Aarti Patel, PharmD Candidate, Tigran Makunts, PharmD, Ruben Abagyan, Ph.D. Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA ABSTRACT RESULTS Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, NSAIDS, are commonly used Cardiovascular ADR Report Frequencies Cardiovascular ADR Report Frequencies Odds ratios of cardiovascular ADR worldwide for their analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, and are deemed out of 100,202 NSAID Reports Among Male and Female Celecoxib Users among Celecoxib male users when safe for over the counter access. NSAIDS as a class have been associated with Myocardial Infarction 4.79 compared to female users cardiovascular, CV, cerebrovascular, CVA, and hypertension, side effects, with Cerebrovascular Accident 3.66 Cerebrovascular 9.69 Accident 11.23 rofecoxib being removed from the market due to these toxicities. However, the Chest Pain 0.85 Cerebrovascular Accident 1.18 risks of heart attack and stroke were deemed similar in all currently marketed Hypertension 0.73 Palpitations 0.49 1.77 NSAIDs. The growing concern over the potentially fatal CV and CVA warranted ADR Hypertension Hypertension 1.16 Hypotension 0.46 ADR 2.05 FEMALES further studies to quantify the associations these side effects. Here, we ADR Atrial Fibrillation MALES analyzed over twelve million reports in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting 0.29 Congestive Heart Failure 0.28 12.16 System, FAERS, to evaluate the reporting odds ratios of hypertension, Myocardial Infarction Myocardial Infarction 2.42 Tachycardia 0.25 myocardial infarction, and stroke in patients taking individual NSAIDs and 25.11 0 1 2 3 4 5 acetaminophen as monotherapy. -

Illinois Medicaid Preferred Drug List

Illinois Medicaid Preferred Drug List Effective January 1, 2020 (Updated January 27, 2020) ▪ The Preferred Drug List (PDL) has products listed in groups by drug class, drug name, dosage form, and PDL status ▪ Multi-source drugs are listed by both brand and generic names when applicable ▪ ADHD Agents: Prior authorization required for participants under 6 years of age and participants 19 years of age and older ▪ Spiriva AER 1.25mcg: Prior authorization NOT required for participants ages 6-17 years ▪ Budesonide: Prior authorization NOT required for participants age 7 years and under ▪ Anticonvulsants: Prior authorization NOT required for non-preferred epilepsy agents for those participants with a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizure disorder in Department records ▪ Antipsychotics: Prior authorization required for participants under 8 years of age and long-term care residents ▪ For drugs not found on this list, go to the drug search engine at: www.ilpriorauth.com Page 1 of 92 DOSAGE DRUG CLASS DRUG NAME PDL STATS FORM ADHD / ANTI-NARCOLEPSY AGENTS : AMPHETAMINES ADZENYS ER SUER NON_PREFERRED AMPHETAMINE ER SUER NON_PREFERRED DYANAVEL XR SUER NON_PREFERRED ADZENYS XR-ODT TBED NON_PREFERRED AMPHETAMINE SULFATE TABS NON_PREFERRED EVEKEO TABS NON_PREFERRED EVEKEO ODT TBDP NON_PREFERRED DEXEDRINE CP24 NON_PREFERRED DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE ER CP24 NON_PREFERRED DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE SOLN NON_PREFERRED PROCENTRA SOLN NON_PREFERRED DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE TABS NON_PREFERRED ZENZEDI TABS NON_PREFERRED VYVANSE CAPS PREFERRED VYVANSE CHEW PREFERRED -

Product Monograph

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH NOVO–KETOROLAC (ketorolac tromethamine) 10 mg Tablets NSAID Analgesic Agent Novopharm Limited Date of Revision: Toronto, Canada August 02, 2007 Control Number 112565 PRODUCT MONOGRAPH NOVO–KETOROLAC (ketorolac tromethamine) 10 mg Tablets THERAPEUTIC CLASSIFICATION NSAID Analgesic Agent ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY NOVO-KETOROLAC (ketorolac tromethamine) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that has analgesic activity. It is considered to be a peripherally acting analgesic. It is thought to inhibit the cyclo-oxygenase enzyme system, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins. At analgesic doses it has minimal anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activity. The peak analgesic effect occurs at 2 to 3 hours post-dosing with no evidence of a statistically significant difference over the recommended dosage range. The greatest difference between large and small doses of administered ketorolac is in the duration of analgesia. Following oral administration, ketorolac tromethamine is rapidly and completely absorbed, and pharmacokinetics are linear following single and multiple dosing. Steady state plasma levels are achieved after one day of q.i.d. dosing. - 2 - Peak plasma concentrations of 0.7 to 1.1 µg/mL occurred at 44 minutes following a single oral dose of 10 mg. The terminal plasma elimination half-life ranged between 2.4 and 9 hours in healthy adults, while in the elderly subjects (mean age: 72 years) it ranged between 4.3 and 7.6 hours. A high fat meal decreased the rate but not the extent of absorption of oral ketorolac tromethamine, while antacid had no effect. In renally impaired patients there is a reduction in clearance and an increase in the terminal half- life of ketorolac tromethamine (See Table 1).