MMWR, Volume 70, Issue 25 — June 25, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

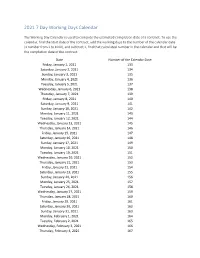

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

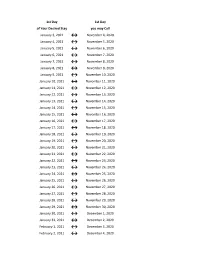

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

Salary Payroll Schedule - 2021 Fiscal Pay Salary Overtime &Retro Leave Semester Pay Period HR Transaction Deadline Payday Days Year Number Entry (PHAHOUR) Periods

Salary Payroll Schedule - 2021 Fiscal Pay Salary Overtime &Retro Leave Semester Pay Period HR Transaction deadline Payday Days Year Number Entry (PHAHOUR) Periods December 25 – January 9 1 Monday, January 4, 2021 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 Friday, January 15, 2021 11 12 January 10 – January 24 2 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 Thursday, January 21, 2021 Monday, February 1, 2021 10 1 January 25 – February 9 3 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 Thursday, February 4, 2021 Tuesday, February 16, 2021 12 February 10 – February 24 4 Tuesday, February 16, 2021 Thursday, February 18, 2021 Monday, March 1, 2021 11 Spring Semester 2 Classes Begin February 25 – March 9 5 Wednesday, March 3, 2021 Friday, March 5, 2021 Tuesday, March 16, 2021 9 1/19/21 Exams End 5/13/21 21 March 10 – March 24 6 Thursday, March 18, 2021 Monday, March 22, 2021 Wednesday, March 31, 2021 11 3 March 25 – April 9 7 Monday, April 5, 2021 Wednesday, April 7, 2021 Friday, April 16, 2021 12 April 10 – April 24 8 Monday, April 19, 2021 Wednesday, April 21, 2021 Friday, April 30, 2021 10 4 April 25 – May 9 9 Monday, May 3, 2021 Wednesday, May 5, 2021 Friday, May 14, 2021 10 May 10 – May 24 10 Tuesday, May 18, 2021 Thursday, May 20, 2021 Tuesday, June 1, 2021 11 Summer I 5 Classes Begin May 25 – June 9 11 Thursday, June 3, 2021 Monday, June 7, 2021 Wednesday, June 16, 2021 12 5/24/21 (Paid 7/1/21) June 10 – June 24 12 Friday, June 18, 2021 Tuesday, June 22, 2021 Thursday, July 1, 2021 11 6 June 25 – July 9 13 Friday, July 2, 2021 Wednesday, July 7, 2021 Friday, July 16, 2021 11 Summer II Classes -

2020-2021 Academic Calendar Revised 9.18.20

FRANCISCAN UNIVERSITY OF STEUBENVILLE 2020-2021 ACADEMIC CALENDAR REVISED 9.18.20 FALL 2020 SEMESTER SPRING 2021 SEMESTER August 24 25-December 11 January 11-May 5 New Student Orientation August 20-23 (Thurs-Sun) January 7-10 (Thurs-Sun) Convocation & Opening of School Mass August 24 (Mon) (4 pm; 3 pm classes January 11 (Mon) (mass only, 10:30 am) shortened & 4:30 pm classes cancelled) Classes begin August 24 (Mon) January 11 (Mon) (10 a.m. classes shortened) Last day for late registration August 28 (Fri) January 15 (Fri) Last day for adding/dropping courses September 2 (Wed) January 20 (Wed) Labor Day (class day) September 7 (Mon) (class day) N/A March for Life N/A January 29 (no day classes) Last day for audit changes September 11 (Fri) January 22 (Fri) Incomplete grades due to registrar September 25 (Fri) February 12 (Fri) Feast of St. Francis October 4 (Sun) N/A Homecoming weekend October 2-4 (Fri-Sun) N/A Midterm deficiencies due to registrar October 14 (Wed) March 5 (Fri) Spring Break N/A March 8-12 (Mon-Fri) (classes resume Mon, March 15) Last day for course withdrawal November 2 (Mon) March 26 (Fri) Tentative Class Make-up Days November 14, 21 (Sat) Thanksgiving vacation November 25-29 (Wed-Sun) N/A (classes resume Mon, Nov 30) Holy Thursday April 1 (no evening classes) Easter recess (Friday & Monday day classes N/A April 2-April 5 (day) canceled; *Monday evening classes do meet) (classes resume Mon evening, April 5, Tuesday day, April 6) Classes Resume Evening: Mon, April 5; Day: Tues, April 6 Last day of classes December 1 (Tues) -

Penndot District 4 Road Report for Week of June 21 to June 25, 2021

TRAVEL ADVISORY June 17, 2021 PennDOT District 4 Road Report for Week of June 21 to June 25, 2021 Dunmore, PA – Below you will find the road report for the week of June 21 - June 25, 2021. The first set of information is our short-term projects and standard of care maintenance projects. The second set of information is our long-term projects which will be updated as work within the project changes. Baseball is back: Please note there will be traffic issues at Davis Street, I-81 and Montage Mountain Road, Moosic, at the beginning and end of the games. Home games Saturday, June 19 game starts at 6:05 PM and Sunday, June 20 game starts at 1:05 PM. Next homes games will be July 6 through July 11. There will be a concert at the Pavilion at Montage on Saturday, June 19 starting at 6:00 PM. Please note that a baseball game and a concert will be going on Saturday, June 19. Short Term Projects Lackawanna State Route/Exit Township Closure/Restriction Work Dates Time I-81 South Abington Township N/A Shoulder Cutting 6/21 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM I-81 Greenfield Township N/A Shoulder Cutting 6/24 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM I-81 Dickson City N/A Sweeping 6/24 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM I-81 Dunmore Borough N/A Sweeping 6/25 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM I-81 Scott Township N/A Shoulder Cutting 6/22-6/23 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM 247 Blakely Borough N/A Patch and Cutting 6/25 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM 347 Dunmore Borough N/A Shoulder Cutting 6/21-6/23 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM 347 Dunmore Borough N/A Crack Seal 6/21-6/22 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM 347 Scott Township N/A Bridge Repair 6/21 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM 407 Waverly -

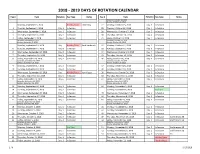

2018 - 2019 Days of Rotation Calendar

2018 - 2019 DAYS OF ROTATION CALENDAR Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Saturday, October 13, 2018 Sunday, October 14, 2018 Monday, September 3, 2018 Holiday/Vaca Labor Day 27 Monday, October 15, 2018 Day 3 In Session 1 Tuesday, September 4, 2018 Day 1 In Session 28 Tuesday, October 16, 2018 Day 4 In Session 2 Wednesday, September 5, 2018 Day 2 In Session 29 Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Day 5 In Session 3 Thursday, September 6, 2018 Day 3 In Session 30 Thursday, October 18, 2018 Day 6 In Session 4 Friday, September 7, 2018 Day 4 In Session 31 Friday, October 19, 2018 Day 1 In Session Saturday, September 8, 2018 Saturday, October 20, 2018 Sunday, September 9, 2018 Sunday, October 21, 2018 Monday, September 10, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Rosh Hashanah 32 Monday, October 22, 2018 Day 2 In Session 5 Tuesday, September 11, 2018 Day 5 In Session 33 Tuesday, October 23, 2018 Day 3 In Session 6 Wednesday, September 12, 2018 Day 6 In Session 34 Wednesday, October 24, 2018 Day 4 In Session 7 Thursday, September 13, 2018 Day 1 In Session 35 Thursday, October 25, 2018 Day 5 In Session 8 Friday, September 14, 2018 Day 2 In Session 36 Friday, October 26, 2018 Day 6 In Session Saturday, September 15, 2018 Saturday, October 27, 2018 Sunday, September 16, 2018 Sunday, October 28, 2018 9 Monday, September 17, 2018 Day 3 In Session 37 Monday, October 29, 2018 Day 1 In Session 10 Tuesday, September 18, 2018 Day 4 In Session 38 Tuesday, October 30, 2018 Day 2 In Session Wednesday, September 19, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Yom Kippur 39 Wednesday, October 31, 2018 Day 3 In Session 11 Thursday, September 20, 2018 Day 5 In Session 40 Thursday, November 1, 2018 Day 4 In Session 12 Friday, September 21, 2018 Day 6 In Session 41 Friday, November 2, 2018 Day 5 In Session Saturday, September 22, 2018 Saturday, November 3, 2018 Sunday, September 23, 2018 Sunday, November 4, 2018 13 Monday, September 24, 2018 Day 1 In Session 42 Monday, November 5, 2018 Day 6 In Session 14 Tuesday, September 25, 2018 Day 2 In Session Tuesday, November 6, 2018 Prof Dev. -

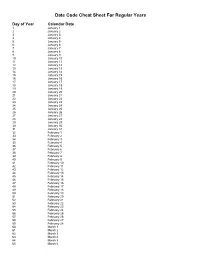

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

Due Date Chart 201803281304173331.Xlsx

Special Event Permit Application Due Date Chart for Events from January 1, 2019 - June 30, 2020 If due date lands on a Saturday or Sunday, the due date is moved to the next business day Event Date 30 Calendar days 90 Calendar Days Tuesday, January 01, 2019 Sunday, December 02, 2018 Wednesday, October 03, 2018 Wednesday, January 02, 2019 Monday, December 03, 2018 Thursday, October 04, 2018 Thursday, January 03, 2019 Tuesday, December 04, 2018 Friday, October 05, 2018 Friday, January 04, 2019 Wednesday, December 05, 2018 Saturday, October 06, 2018 Saturday, January 05, 2019 Thursday, December 06, 2018 Sunday, October 07, 2018 Sunday, January 06, 2019 Friday, December 07, 2018 Monday, October 08, 2018 Monday, January 07, 2019 Saturday, December 08, 2018 Tuesday, October 09, 2018 Tuesday, January 08, 2019 Sunday, December 09, 2018 Wednesday, October 10, 2018 Wednesday, January 09, 2019 Monday, December 10, 2018 Thursday, October 11, 2018 Thursday, January 10, 2019 Tuesday, December 11, 2018 Friday, October 12, 2018 Friday, January 11, 2019 Wednesday, December 12, 2018 Saturday, October 13, 2018 Saturday, January 12, 2019 Thursday, December 13, 2018 Sunday, October 14, 2018 Sunday, January 13, 2019 Friday, December 14, 2018 Monday, October 15, 2018 Monday, January 14, 2019 Saturday, December 15, 2018 Tuesday, October 16, 2018 2019 Tuesday, January 15, 2019 Sunday, December 16, 2018 Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Wednesday, January 16, 2019 Monday, December 17, 2018 Thursday, October 18, 2018 Thursday, January 17, 2019 Tuesday, December 18, 2018 -

2021 Park Hours

Holiday World & Splashin' Safari 2021 Operating Calendar May, 2021 Holiday World Hours Splashin' Safari Hours Special Events Saturday, May 1 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Sunday, May 2 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Monday, May 3 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Tuesday, May 4 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Wednesday, May 5 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Thursday, May 6 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Friday, May 7 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Saturday, May 8 Platinum Season Pass Preview Day: Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 6 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Platinum Season Passholder Party Sunday, May 9 Passholder Preview Day: Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 6 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Monday, May 10 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Tuesday, May 11 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Wednesday, May 12 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Thursday, May 13 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Friday, May 14 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed for a private outing Saturday, May 15 Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 4 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Sunday, May 16 Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 4 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Monday, May 17 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Tuesday, May 18 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Wednesday, May 19 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Thursday, May 20 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Friday, May 21 Holiday -

FINAL REVISED Final Agenda Mineral County Board of Commissioners June 21, 2021 – June 25, 2021

FINAL REVISED Final Agenda Mineral County Board of Commissioners June 21, 2021 – June 25, 2021 Monday June 21, 2021 Tuesday June 22, 2021 MACo Executive Board Meetings- Helena- Commissioner Zylawy Wednesday June 23, 2021 8:30 AM-9:15 AM Interviews for Deputy- Commissioner Johnston 9:30 AM until finished Verbiage clarification/clean up in Policy Handbook MACo Executive Board Meetings- Helena- Commissioner Zylawy Thursday June 24, 2021 12:00 PM – 2:00 PM Hospital Board Meeting- Commissioner Johnston Friday June 25, 2021 As time permits: Administrative Business: claims and approval for June 25, 2021, minutes review and approval of June 18, 2021; sign documents as needed 9:00 AM-10:00 AM Forest Service Update- Carole Johnson 10:00 AM- 10:30 AM Sheriff Toth- purchasing laptops with federal drug forfeiture money (and Cares Act money if needed)- possible Action Item; Discuss MHP rent 10:30 AM- 11:00 AM HERE Global GIS Information Purchase- Action Item-Andy Short 11:00 AM- 11:30 AM FMLA Intermittent Leave -Discussion regarding Mineral County FMLA P&P – Melanie Batt- Possible Action Item 11:30 AM- 12:00 PM Public Comment The Board of County Commissioners meet in regular session the first Thursday of every month and on every Friday between the hours of 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. or until business is complete, with a break at noon. There may be issues discussed during the meeting which may not be listed on the agenda. If a decision is required on items of significant interest, it will be scheduled for another date/time and posted.