Source Segregation of Biowaste in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calendario Terza Categoria

* COMITATO * F. I. G. C. - LEGA NAZIONALE DILETTANTI * LOMBARDIA * ************************************************************************ * * * TERZA CATEGORIA MILANO GIRONE: A * * * ************************************************************************ .--------------------------------------------------------------. .--------------------------------------------------------------. .--------------------------------------------------------------. I ANDATA: 18/09/16 ! ! RITORNO: 29/01/17 I I ANDATA: 23/10/16 ! ! RITORNO: 5/03/17 I I ANDATA: 27/11/16 ! ! RITORNO: 9/04/17 I I ORE...: 15:30 ! 1 G I O R N A T A ! ORE....: 14:30 I I ORE...: 15:30 ! 6 G I O R N A T A ! ORE....: 14:30 I I ORE...: 14:30 ! 11 G I O R N A T A ! ORE....: 15:30 I I--------------------------------------------------------------I I--------------------------------------------------------------I I--------------------------------------------------------------I I ATLETICO MILANO - AUDACE 1943 I I ATLETICO MILANO - IRIS 1914 I I GROSSMAN - BAGGIO SECONDO I I BAGGIO SECONDO - VICTORIA MMVII A.S.D. I I IDROSTAR - BAGGIO SECONDO I I ORIONE - AUDACE 1943 I I FORNARI SPORT - ORIONE I I ORIONE - REAL BOVISA I I POL.OR.S.LUIGI CORSICO - RED DEVILS CORSICO I I GROSSMAN - RED DEVILS CORSICO I I POL.OR.S.LUIGI CORSICO - GROSSMAN I I REAL BOVISA - FORNARI SPORT I I IDROSTAR - POL.OR.S.LUIGI CORSICO I I RED DEVILS CORSICO - FORNARI SPORT I I S.G.B. - IDROSTAR I I IRIS 1914 - S.G.B. I I VICTORIA MMVII A.S.D. - S.G.B. I I VICTORIA MMVII A.S.D. - ATLETICO MILANO I I Riposa............... -

Fascicolo II/1

1 INDICE Cap. 1 INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE E CENNI STORICI PAG. 3 Cap. 2 QUADRO CONOSCITIVO, RICOGNITIVO E PROGRAMMATORIO DI CASTANO PRIMO E DEL TERRITORIO CIRCOSTANTE PAG. 11 Cap. 3 DOTAZIONE PRO CAPITE DI VOLUME RESIDENZIALE E DI AREE A SERVIZI, VERDE E PARCHEGGI PAG. 31 Cap. 4 RIPIANIFICAZIONE DEGLI “STANDARD” DECADUTI PAG. 33 Cap. 5 STATO DI ATTUAZIONE DEI PA E ANALISI DELLE AREE DESTINATE ALLA ESPANSIONE DEL TESSUTO URBANIZZATO DEL P.R.G. (art. 84 delle NdA del PTCP) PAG. 35 Cap. 6 VINCOLI PAESAGGISTICI E SISTEMA PAESISTICO AMBIENTALE. INDIVIDUAZIONE DEI PRINCIPALI ELEMENTI CHE CARATTERIZZANO IL PAESAGGIO PAG. 41 Cap. 7 SUPERFICIE URBANIZZATA. INDICATORI DI SOSTENIBILITA‟, POLITICHE E AZIONI DI RIQUALIFICAZIONE PAG. 61 Cap. 8 CONSUMO DEL SUOLO. INCREMENTO DELLA SUPERFICIE URBANIZZATA E DOTAZIONE DI RISERVA DELLA SUPERFICIE FONDIARIA PAG. 71 Cap. 9 ZONE DI INIZIATIVA COMUNALE ORIENTATA I.C. (art. 12 NdA del PTC del Parco Ticino) PAG. 75 Castano Primo - P.G.T. con modifiche introdotte a seguito dell‟accoglimento di osservazioni – Parte Prima – Fascicolo II 2 Castano Primo - P.G.T. con modifiche introdotte a seguito dell‟accoglimento di osservazioni – Parte Prima – Fascicolo II 3 Capitolo 1 INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE E CENNI STORICI 1 Castano Primo è identificato come un centro di rilevanza sovracomunale nel vigente Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento della Provincia di Milano. Il PTCP individua anche la stazione ferroviaria de Le Nord come interscambio di rilevanza sovracomunale. Inoltre negli studi provinciali per l‟adeguamento del PTCP alla LR 12/2005, Castano è indicato come sede di un progetto di centro polifunzionale di rilevanza sovracomunale e, a tutti gli effetti, come Polo attrattore di primo livello, qualifica attribuita solo a 17 Comuni di tutta la Provincia. -

Distretti Veterinari Distretti Veterinari

DISTRETTI VETERINARI DISTRETTO VETERINARIO n.1 DISTRETTO VETERINARIO n.2 DISTRETTO VETERINARIO n.3 Comprende gli ambiti territoriali delle aree dei Distretti 1 Comprende gli ambiti territoriali delle aree dei Distretti 4 Comprende gli ambiti territoriali delle aree dei Distretti 6 (Garbagnate), 2 (Rho) e 3 (Corsico) (Legnano) e 5 (Castano Primo) (Magenta) e 7 (Abbiategrasso) Elenco comuni Distretto Veterinario n. 1: Elenco comuni Distretto Veterinario n. 2: Elenco comuni Distretto Veterinario n. 3: Arese - Assago - Baranzate - Bollate - Buccinasco - Cesano Bo- Arconate - Bernate Ticino - Buscate - Busto Garolfo - Canegrate - Abbiategrasso - Albairate - Arluno - Bareggio - Besate - Boffalora scone - Cesate - Cornaredo - Corsico - Cusago -Garbagnate Mila- Castano Primo - Cerro Maggiore - Cuggiono - Dairago - Inveruno sopra Ticino - Bubbiano - Calvignasco - Casorezzo - Cassinetta di nese - Lainate - Novate Milanese - Paderno Dugnano - Pero - Legnano - Magnano - Nerviano - Nosate - Parabiago - Rescaldina - Lugagnano - Cisliano - Corbetta - Gaggiano - Gudo Visconti - Ma- Pogliano Milanese - Pregnana Milanese - Rho - Senago - Settimo Robecchetto con Induco - San Giorgio su Legnano - Turbigo - San genta - Marcallo con Casone - Mesero - Moribondo - Motta Visconti - Ossona - Ozzero - Robecco sul Naviglio - Rosate - S. Stefano Milanese - Solaro - Trezzano sul Naviglio - Vanzago - Vittore Olona - Vanzaghello - Villa Cortese Ticino - Sedriano - Vermezzo - Vittuone - Zelo Surrigone Sede e Direzione: Tel. 02 93923330/5 Sede e Direzione: Tel. 0331 498529 -

Milan and the Lakes Travel Guide

MILAN AND THE LAKES TRAVEL GUIDE Made by dk. 04. November 2009 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Attractions Milan and the Lakes Travel Guide Leonardo’s Last Supper The Last Supper , Leonardo da Vinci’s 1495–7 masterpiece, is a touchstone of Renaissance painting. Since the day it was finished, art students have journeyed to Milan to view the work, which takes up a refectory wall in a Dominican convent next to the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The 20th-century writer Aldous Huxley called it “the saddest work of art in the world”: he was referring not to the impact of the scene – the moment when Christ tells his disciples “one of you will betray me” – but to the fresco’s state of deterioration. More on Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) Crucifixion on Opposite Wall Top 10 Features 9 Most people spend so much time gazing at the Last Groupings Supper that they never notice the 1495 fresco by Donato 1 Leonardo was at the time studying the effects of Montorfano on the opposite wall, still rich with colour sound and physical waves. The groups of figures reflect and vivid detail. the triangular Trinity concept (with Jesus at the centre) as well as the effect of a metaphysical shock wave, Example of Ageing emanating out from Jesus and reflecting back from the 10 Montorfano’s Crucifixion was painted in true buon walls as he reveals there is a traitor in their midst. fresco , but the now barely visible kneeling figures to the sides were added later on dry plaster – the same method “Halo” of Jesus Leonardo used. -

Elenco 23 Accordi Sottoscritti.Xlsx

POR FESR 2014‐2020 ‐ MISURA MOBILITA' CICLISTICA ‐ ELENCO ACCORDI SOTTOSCRITTI SOGGETTI COMUNI DATA SOGGETTO CONTRIBUTO n. ID PROGETTO SOTTOSCRITTORI TERRITORIALMENTE DENOMINAZIONE PROGETTO COSTO PROGETTO SOTTOSCRIZIONE BENEFICIARIO/CAPOFILA ASSEGNATO DELL'ACCORDO INTERESSATI ACCORDO ASSAGO ASSAGO BASIGLIO BASIGLIO 1 115892 COMUNE ASSAGO BUCCINASCO BUCCINASCO “PIU’ BICI” ‐ Asse nord. € 1.829.501,46 € 1.165.351,34 22 dicembre 2016 PIEVE EMANUELE PIEVE EMANUELE ZIBIDO S. GIACOMO ZIBIDO S. GIACOMO BINASCO BINASCO NOVIGLIO NOVIGLIO 2 119424 COMUNE BINASCO “RISI & BICI” € 862.332,68 € 603.632,86 21 dicembre 2016 ROSATE ROSATE GAGGIANO GAGGIANO PIU’ BICI! 3 119252 COMUNE BRESCIA BRESCIA BRESCIA Progetto della mobilità ciclistica nella città di € 2.300.000,00 € 1.472.827,40 22 dicembre 2016 Brescia. “Interventi di mobilità ciclabile di completamento 4 116812 COMUNE CASSINA DE PECCHI CASSINA DE PECCHI CASSINA DE PECCHI € 712.678,93 € 464.595,09 23 dicembre 2016 alla rete esistente”. d.d.s. n. 16241 del 15 CASTANO PRIMO CASTANO PRIMO Un anello ciclabile di collegamento tra i due dicembre 2017 ‐ 5 120318 COMUNE CASTANO PRIMO CUGGIONO CUGGIONO percorsi ciclabili regionali sito nei territori dei € 955.171,35 € 633.059,97 decadenza del contributo BUSCATE comuni di Castano Primo, Cuggiono e Buscate. di cui all'Accordo del 16 dicembre 2016 Nuova pista ciclabile di collegamento tra Via XXV Aprile e Via De Ponti, nell’ambito della 6 117495 COMUNE CINISELLO BALSAMO CINISELLO BALSAMO CINISELLO BALSAMO realizzazione del percorso ciclabile di collegamento € 863.000,00 € 602.798,32 15 dicembre 2016 tra il PCIR (percorso n° 6 – Villoresi) e la nuova stazione MM1 – Bettola – (Lotto 2). -

Distretto Ambito Distrettuale Comuni Abitanti Ovest Milanese Legnano E

Ambito Distretto Comuni abitanti distrettuale Busto Garolfo, Canegrate, Cerro Maggiore, Dairago, Legnano, Nerviano, Legnano e Parabiago, Rescaldina, S. Giorgio su Legnano, S. Vittore Olona, Villa 22 254.678 Castano Primo Cortese ; Arconate, Bernate Ticino, Buscate, Castano Primo, Cuggiono, Inveruno, Magnano, Nosate, Robecchetto con Induno, Turbigo, Vanzaghello Ovest Milanese Arluno, Bareggio, Boffalora sopra Ticino, Casorezzo, Corbetta, Magenta, Magenta e Marcallo con Casone, Mesero, Ossona, Robecco sul Naviglio, S. Stefano 28 211.508 Abbiategrasso Ticino, Sedriano, Vittuone; Abbiategrasso, Albairate, Besate, Bubbiano, Calvignasco, Cisliano, Cassinetta di Lugagnano, Gaggiano, Gudo Visconti, Morimomdo, Motta Visconti, Ozzero, Rosate, Vermezzo, Zelo Surrigone Garbagnate Baranzate, Bollate, Cesate, Garbagnate Mil.se, Novate Mil.se, Paderno 17 362.175 Milanese e Rho Dugnano, Senago, Solaro ; Arese, Cornaredo, Lainate, Pero, Pogliano Rhodense Mil.se, Pregnana Mil.se, Rho, Settimo Mil.se, Vanzago Assago, Buccinasco, Cesano Boscone, Corsico, Cusago, Trezzano sul Corsico 6 118.073 Naviglio Sesto San Giovanni, Cologno Monzese, Cinisello Balsamo, Bresso, Nord Milano Nord Milano 6 260.042 Cormano e Cusano Milanino Milano città Milano Milano 1 1.368.545 Bellinzago, Bussero, Cambiago, Carugate, Cassina de Pecchi, Cernusco sul Naviglio, Gessate, Gorgonzola, Pessano con Bornago, Basiano, Adda Grezzago, Masate, Pozzo d’Adda, Trezzano Rosa, Trezzo sull’Adda, 28 338.123 Martesana Vaprio d’Adda, Cassano D’Adda, Inzago, Liscate, Melzo, Pozzuolo Martesana, -

PRODUZIONE PRO-CAPITE - Anno 2019 - DM 26 MAGGIO 2016

PRODUZIONE PRO-CAPITE - Anno 2019 - DM 26 MAGGIO 2016 - Rescaldina Solaro Trezzo sull'Adda Cesate Legnano Grezzago Cerro Maggiore Trezzano Rosa Vanzaghello San Vittore Olona Basiano Magnago Vaprio d'Adda San Giorgio su Legnano Garbagnate MilaneseSenago Paderno Dugnano Cambiago Pozzo d'Adda Dairago Villa Cortese Canegrate Lainate Masate Cinisello Balsamo Nosate Gessate Nerviano Cusano Milanino Castano Primo Parabiago Arese Bollate Carugate Pessano con Bornago Buscate Busto Garolfo Inzago Arconate Cormano Pogliano Milanese Bresso Bussero Sesto San GiovanniCologno Monzese Bellinzago Lombardo Rho Novate Milanese Cernusco sul Naviglio Gorgonzola Turbigo Casorezzo Baranzate Cassano d'Adda Inveruno Robecchetto con Induno Vanzago Cassina de' Pecchi Pregnana Milanese Vimodrone Pozzuolo Martesana Pero Arluno Cuggiono Ossona Cornaredo Vignate Melzo Mesero Pioltello Santo Stefano Ticino Sedriano Marcallo con Casone Segrate Settimo Milanese Truccazzano Bernate Ticino Vittuone Bareggio Rodano Liscate Milano Boffalora sopra Ticino Corbetta Magenta Settala Cusago Cesano Boscone Peschiera Borromeo Pantigliate Cisliano Corsico Cassinetta di Lugagnano Albairate Robecco sul Naviglio Trezzano sul Naviglio Buccinasco Paullo San Donato Milanese Mediglia Tribiano Gaggiano Assago Abbiategrasso Vermezzo con Zelo Rozzano San Giuliano Milanese Colturano Opera Gudo Visconti Dresano Ozzero Noviglio Locate di Triulzi Zibido San Giacomo Vizzolo Predabissi Pieve Emanuele Melegnano Rosate Basiglio Morimondo Carpiano Binasco Cerro al Lambro BubbianoCalvignasco San Zenone -

646 CASTANO P./CUGGIONO/MARCALLO C.C./MAGENTA 1 Linea Andata COD

San Vittore O. Via Roma 75 -MI- tel. 0331.519423 - www.movibus.it dal 7 gennaio 2016 646 CASTANO P./CUGGIONO/MARCALLO C.C./MAGENTA 1 linea andata COD. CORSA 104 106 108 110 112 504 116 152 122 124 126 132 508 182 138 140 142 144 150 COD. FERMATA FERMATA CADENZA FR6 FR6 FR6 SCO FR6 SCO FR6 FR6 FR6 FR6 FR6 FR6 SC5 FR6 FR5 FR6 FR5 FR6 FR5 MG888 MAGENTA Via Tobagi (dep.ATINOM) 6.10 6.30 6.55 7.10 7.25 8.35 9.20 10.20 11.20 15.10 16.10 17.10 18.10 19.00 MG797 MAGENTA Via Dello Stadio, 35 6.13 6.33 6.58 7.13 7.28 8.38 9.23 10.23 11.23 12.15 13.15 14.05 14.15 15.13 16.13 17.13 18.13 19.03 MG702 MAGENTA V. Donatori D.Sangue,40 OSPEDALE 6.15 6.35 7.00 7.15 7.30 8.40 9.25 10.25 11.25 12.17 13.17 14.07 14.17 15.15 16.15 17.15 18.15 19.05 MG801 MAGENTA Via Cavallari, 39 6.17 6.37 7.02 7.17 7.32 8.42 9.27 10.27 11.27 12.19 13.19 14.09 14.19 15.17 16.17 17.17 18.17 19.07 MG306 MAGENTA Via Novara, 95 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- 8.10 ----- ----- ----- ----- 12.20 13.20 ----- 14.20 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- MG501 MAGENTA Via Novara, 15 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- 8.12 ----- ----- ----- ----- 12.23 13.23 ----- 14.23 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- MG561 MAGENTA Via Brocca,41 zona STAZIONE ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- 8.15 ----- ----- ----- ----- 12.26 13.26 ----- 14.26 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- MG802 MAGENTA Via Espinasse, 36 6.19 6.39 7.04 7.19 7.34 8.17 8.44 9.29 10.29 11.29 12.28 13.28 14.12 14.28 15.19 16.19 17.19 18.19 19.09 MC020 MARCALLO CON CASONE S.P.31 Via Roma fr Civ.72 6.23 6.43 7.08 7.23 7.38 8.21 8.48 9.33 10.33 11.33 12.34 13.34 -

Allegato 2 All'autorizzazione Dirigenziale Atti RG N.3023 Del 31/03/2015 Riorganizzazione Del Servizio Di Trasporto Relativo Al Lotto 6

Allegato 2 all’Autorizzazione Dirigenziale atti R.G. n.3023 del 31/03/2015 Riorganizzazione del servizio di trasporto relativo al Lotto 6 Z601 Legnano - San Vittore Olona - Nerviano - Rho - Milano (M. Dorino M1) • Soppressione dell’ultima coppia di corse Feriale 5 e Sabato in tarda serata. • Rimodulazione dell’orario delle corse con capolinea Milano Cadorna. • Ricalibrazione e riduzione delle corse nelle giornate di Sabato nel periodo scolastico. • Riduzione del servizio Festivo mediante soppressione di 3 coppie di corse. • Riduzione del servizio nel mese di Agosto Z606 San Vittore Olona - Cerro Maggiore - Nerviano - Rho - Milano (M. Dorino M1) • Soppressione di 2 coppie di corse Feriale 5 una in prima mattinata e una nel tardo pomeriggio. • Variazione di periodicità di una coppia di corse da Scolastica a Scolastica 5. Z607 Nerviano (Villanova) - Lainate (Barbaiana) • Viene mantenuto solo una corsa mattinale di collegamento tra Nerviano (Villanova) e Lainate (Barbaiana) in via sperimentale fino al termine della stagione scolastica. • Gli utenti possono interscambiare con tutte le linee che transitano da Barbaiana lungo l’asse del Sempione. Z608 Stabilimenti Nerviano - Milano (M. Dorino M1) • La linea viene soppressa. Z609 Legnano - San Vittore Olona - Nerviano - Rho (Fiera M1) • La linea passa da 5 a 11 coppie di corse in occasione dell’Expo, le corse verranno effettuate con periodicità Feriale 6. Z611 Legnano - San Giorgio su Legnano - Canegrate - Parabiago - Ospedale Nuovo • L’ultima coppia di corse serali vengono attestate a Canegrate. Z612 Legnano - Cerro Maggiore - Lainate • Soppressione di 2 coppie di corse Feriale 6 una in prima mattinata e una nel tardo pomeriggio. • Variazione di periodicità di una coppia di corse da Scolastica a Scolastica 5. -

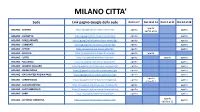

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

MILANO CITTA’ Sede Link pagina Google della sede Dal 3 al 7 Dal 10 al 14 Dal 17 al 21 Dal 24 al 28 aperto MILANO - CENTRO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-centro?gm aperto aperto dall'11 al 13 MILANO - CORVETTO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-corvetto?gm aperto aperto MILANO - FORZE ARMATE https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-forze-armate?gm aperto aperto MILANO - LAMBRATE https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-lambrate?gm aperto aperto MILANO - AFFORI https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-affori?gm aperto aperto MILANO - BICOCCA https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-bicocca?gm aperto aperto MILANO - LOTTO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-lotto?gm aperto aperto aperto MILANO - NIGUARDA https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-niguarda?gm aperto aperto MILANO - QUARTO OGGIARO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-quarto-oggiaro?gm aperto aperto MILANO - CHIESA ROSSA https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-chiesa-rossa?gm aperto aperto MILANO - GALLARATESE REGINA PACIS https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-gallaratese?gm aperto aperto aperto MILANO - LORENTEGGIO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-lorenteggio?gm aperto aperto il 10 e l’11 MILANO - SAN CRISTOFORO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-san-cristoforo?gm aperto aperto MILANO - SANT'AMBROGIO https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-sant-ambrogio?gm aperto aperto MILANO - SARPI https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-sarpi?gm aperto aperto aperto MILANO - VITTORIA VIGENTINA https://g.page/caf-acli-milano-vigentina?gm aperto dal 18 al 21 ZONA EST PROVINCIA DI MILANO Sede Link pagina Google della sede Dal 3 al 7 Dal 10 al 14 Dal 17 al 21 Dal 24 al 28 CARUGATE https://g.page/caf-acli-carugate?gm -

The Ticino River and the Natural the Waters 17 Environments of Its Valley, Carved by the River Wildlife 18 While Going from Lago Maggiore to the Po River

TICINO PARK A guide to this nature preserve in Lombardy: the river, the wildlife, flora, projects and events, useful addresses and itineraries (& ##%& CONTENTS PREMISE A FUTURE ORIENTED PARK Lengthy articles could be written about the Ticino Valle del Ticino 4 Valley Park in Lombardy, recounting its history, Objective: Sustainability 6 features, all the activities it carries out and the Biosphere One Park, Two Souls 9 projects it is trying to implement amid a thousand The Importance of Planning 10 obstacles. In the following pages, we have tried Waterways for Biodiversity 11 to highlight the main facets of an area rich in Reserve Projects for the Future 12 nature and beautiful landscapes, but also human Natura 2000 Network 13 histories and historical and art testimonies. We would like to take you on a journey in A PARK discovery of the Park. Every section is a stage in FULL OF LIFE 14 our itinerary and our objective is that, by the end, you can share the idea underlying this preserve: A Green Corridor 16 the protection of the Ticino river and the natural The Waters 17 environments of its valley, carved by the river Wildlife 18 while going from Lago Maggiore to the Po River. Park Rangers and Volunteers 20 This are is an immeasurable treasury, also from a The World of Plants 21 social viewpoint, of which we are owners and The Agricultural Landscape 22 Since 2002 the Ticino Valley is included among the global biosphere reserves guardians and that, all together, we are called to love and protect. network, that Unesco recognized under the MAB Programme (Man and A PARK FOR EVERYONE 24 Biosphere). -

Consolidated Financial Statement 2020

Consolidated financial statements of the CAP Group as at 31 December 2020 for Shareholders’ meeting 25 May 2021 (Translation from the Italian original which remains the definitive version) - 1 - Table of Contents Management Report………….…………...…………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Financial Statements…………..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………70 Statement of Financial Position………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………71 Statement of Comprehensive Income…………………………………………………………………………………………………..72 Cash Flow Statement…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….73 Changes in shareholders’ equity………………………………………………………………………………………….……………….74 Explanatory notes to the financial statements………………………………………………………………………………….75 General information…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………….75 Summary of Accounting Standards……………………………………………………………………………………………………….75 Financial risk management………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………….86 Going concern……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……..……..88 Estimates and assumptions…………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………88 Disclosure by operating segments…………………………………………………………………………………………………………91 Notes to the Consolidated Statement of Financial Position…………………………………………………….…………….91 Notes to the Consolidated Statement of comprehensive income………………………………………………………..107 Related party transactions……………………………………………………………………………………………………….………….114 Contractual commitments, Guarantees and Concessions………………………………………………………….………..115 Fees to directors and statutory auditors………………………………………………………………………………………………115