State of Play Southeast Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Bowl Lv Team Media Availability Schedule

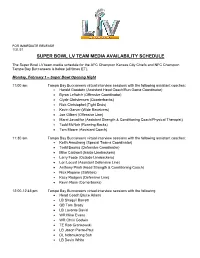

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 1/31/21 SUPER BOWL LV TEAM MEDIA AVAILABILITY SCHEDULE The Super Bowl LV team media schedule for the AFC Champion Kansas City Chiefs and NFC Champion Tampa Bay Buccaneers is below (all times ET). Monday, February 1 – Super Bowl Opening Night 11:00 am Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following assistant coaches: • Harold Goodwin (Assistant Head Coach/Run Game Coordinator) • Byron Leftwich (Offensive Coordinator) • Clyde Christensen (Quarterbacks) • Rick Christophel (Tight Ends) • Kevin Garver (Wide Receivers) • Joe Gilbert (Offensive Line) • Maral Javadifar (Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach/Physical Therapist) • Todd McNair (Running Backs) • Tom Moore (Assistant Coach) 11:30 am Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following assistant coaches: • Keith Armstrong (Special Teams Coordinator) • Todd Bowles (Defensive Coordinator) • Mike Caldwell (Inside Linebackers) • Larry Foote (Outside Linebackers) • Lori Locust (Assistant Defensive Line) • Anthony Piroli (Head Strength & Conditioning Coach) • Nick Rapone (Safeties) • Kacy Rodgers (Defensive Line) • Kevin Ross (Cornerbacks) 12:00-12:45 pm Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following: • Head Coach Bruce Arians • LB Shaquil Barrett • QB Tom Brady • LB Lavonte David • WR Mike Evans • WR Chris Godwin • TE Rob Gronkowski • LB Jason Pierre-Paul • DL Ndamukong Suh • LB Devin White 4:00-4:45 pm Kansas City Chiefs virtual interview sessions with the following: • Head Coach Andy Reid • DE Frank Clark • RB -

Übungsleiterkurs 2018 Geschichte Des Faustballsports

04.04.2018 Übungsleiterkurs 2018 Geschichte des Faustballsports, Organisationslehre Karl Weiß, Ehrenpräsident des OÖFBV Karl Weiß Präsident der International Fistball Association 39 Jahre Funktionär beim ASKÖ Urfahr, seit 2014 Ehrenobmann 42 Jahre Funktionär im OÖFBV, seit 2014 Ehrenpräsident 29 Jahre Funktionär im ÖFBB, seit 2011 Ehrenpräsident 19 Jahre Funktionär in IFA, seit 2011 Präsident Sportliche Ausbildungen: 1976 Staatl. Lehrwarteausbildung Faustball 1981 Staatl. Trainerausbildung Faustball 1983 Bundesschiedsrichterausbildung 1987 Ausbildung zum IFA Schiedsrichter Goldenes Ehrenzeichen für Verdienste um die Republik Österreich (06) Bundessportorganisation: Funktionär des Jahres 2008 Konsulent der oö. Landesregierung für das Sportwesen (11) 1 04.04.2018 Geschichte des Faustballsports Das Faustballspiel ist einer der ältesten Sportarten der Welt. Erstmals erwähnt wurde das Faustballspiel im Jahr 240 n. Chr. von Gordianus, Kaiser von Rom. Im Jahr 1555 schreibt Antonio Scaino die ersten Regeln für den italienischen Volkssport, das "Ballenspiel". Johann Wolfgang von Goethe schreibt in seinem Tagebuch 1786 "Italienische Reise": "Vier edle Veroneser schlugen den Ball gegen vier Vicenter; sie trieben das sonst unter sich, das ganze Jahre, etwa zwei Stunden vor Nacht". 1870 wird das Spiel in Deutschland wieder entdeckt und der Deutsche Georg Heinrich Weber verfasst 1896 das erste deutsche Regelwerk. Populär wurde das Faustballspiel unter Turnvater Jahr in Deutschland und ist bis heute noch in den Turnvereinen als Ausklangspiel verankert. -

An Evening at the Academy Shines Bright in Support of SMA's Bursary Fund

TorchMagazine for Alumnae and Friends of St. Mary’sLight Academy Fall 2016 An Evening at the Academy shines bright in support of SMA’s Bursary Fund St. Mary’s Academy | 550 Wellington Crescent | Winnipeg, Manitoba | R3M 0C1 stmarysacademy.mb.ca | facebook.com/smawinnipeg | twitter.com/smawpg Torch Light Published annually by St. Mary’s Academy Editor Georgina (Gina) Borkofski [email protected] Graphic Design Torch Light Georgina (Gina) Borkofski Amy Houston ’03 Contributing Writers st. mary’s academy Georgina (Gina) Borkofski Sr. Michelle Garlinski ’89, SNJM Amy Houston ’03 year in review Georgine Van de Mosselaer ’83 Sr. Susan Wikeem ’63, SNJM President’s Message . 2 Connie Yunyk (Scerbo ’77) Bursary Fund . 3 Photo Credits Georgina (Gina) Borkofski Gonzaga Middle School . 4 Jasmine Gilchrist ’17 Amy Houston ’03 SNJM Provincial Leadership . 5 Chris O’Donoghue Charism and Mission Office . 5 Around the Academy . 6 ST. MARY’S ACADEMY President Staff News . 11 Connie Yunyk (Scerbo ’77) Burning Bright Speaker Series . 12 [email protected] Acting Senior School Principal Marian Awards for Excellence . 13 Michelle Klus [email protected] Alumnae President’s Message . 15 Acting Junior School Principal Homecoming 2016 . 16 Carol-Ann Swayzie (van Es ’80) From the Alumnae Office . 18 [email protected] The Grapevine . 19 Director of Communications and Births . 25 Marketing In Memoriam . 25 Georgina (Gina) Borkofski [email protected] From the Advancement Office . 26 Director of Advancement and Donor Recognition . 27 Alumnae Affairs Georgine Van de Mosselaer ’83 Coming Events . 30 [email protected] Alumnae, Advancement and Special Events Coordinator Amy Houston ’03 [email protected] Editor’s Note Phone St. -

Board of Regents Meeting

Board of Regents Meeting Varner Hall Board Room 3835 Holdrege Street Lincoln, NE, 68583-0745 NOTICE OF MEETING Notice is hereby given that the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska will meet in a publicly convened session on Friday, June 25, 2021, at 9:00 a.m. in the board room of Varner Hall, 3835 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. An agenda of subjects to be considered at said meeting, kept on a continually current basis, is available for inspection in the office of the Corporation Secretary of the Board of Regents, Varner Hall, 3835 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, Nebraska, or at https://nebraska.edu/regents/agendas‐minutes A copy of this notice will be delivered to the Lincoln Journal Star, the Omaha World‐Herald, the Daily Nebraskan, the Gateway, the Antelope, the Kearney Hub, the Lincoln office of the Associated Press, members of the Board of Regents, and the President’s Council of the University of Nebraska. Dated: June 18, 2021 Stacia L. Palser Interim Corporation Secretary Board of Regents University of Nebraska Board of Regents Varner Hall | 3835 Holdrege Street | Lincoln, NE 68583-0745 | 402.472.3906 | FAX: 402.472.1237 | nebraska.edu/regents AGENDA THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA Varner Hall, 3835 Holdrege Street Lincoln, NE 68583-0745 Friday, June 25, 2021 9:00 a.m. I. CALL TO ORDER II. ROLL CALL III. APPROVAL OF MINUTES AND RATIFICATION OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON May 1, 2021 IV. PRESENTATIONS Governor Pete Ricketts V. KUDOS Michael Christen, University of Nebraska at Kearney Scott Kurz, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Juli Bohnenkamp, University of Nebraska Medical Center Sarah Weil, University of Nebraska at Omaha VI. -

HOW to DESIGN an AMERICAN NINJA WARRIOR COURSE Like a Pro

instructables HOW TO DESIGN AN AMERICAN NINJA WARRIOR COURSE Like a Pro by howtobasic123 Every week, millions of viewers tune in to NBC's am in the process of making three more American American Ninja Warrior, to watch as ninjas from Ninja Warrior styled instructables. I have now every walk of life attempt to complete a series of completed building more than 10 different backyard iconic obstacles of increasing difficulty in the hope of courses (i'm pretty much an expert ninja warrior becoming an American Ninja Warrior. To many course builder) and through this Instructable I hope to American Ninja Warrior is just a source of aid people all over the world enjoy American Ninja entertainment but to many its a way of life. As the Warrior as much as I do. In this instructable i will give American Ninja Warrior community grows and gyms you my pro tips on creating your own american ninja start coming up all over the world there has a been an warrior course increase in the need for ninja specific training tools and course plans. This is my first instructable and I HOW TO DESIGN AN AMERICAN NINJA WARRIOR COURSE Like a Pro: Page 1 Step 1: Designing Your Own Course There are many things to consider when designing a Things to consider: Ninja Warrior training course in your backyard or home. Many people think that they can just go to One of the most important things to consider is where home depot, get materials and start building. Sadly its to place your new American Ninja Warrior course. -

Masculinity and the National Hockey League: Hockey’S Gender Constructions

MASCULINITY AND THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE: HOCKEY’S GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _______________________________________________________ by JONATHAN MCKAY Dr. Cristian Mislán, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright by Jonathan McKay 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled: MASCULINITY AND THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE: HOCKEY’S GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS presented by Jonathan McKay, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cristina Mislán Professor Sandy Davidson Professor Amanda Hinnant Professor Becky Scott MASCULINITY AND THE NHL Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking my committee chair, Dr. Cristina Mislán, for her guidance and help throughout this project, and beyond. From the first class I took at Missouri, Mass Media Seminar, to the thesis itself, she encouraged me to see the world through different lenses and inspired a passion for cross-disciplined study. Her assistance was invaluable in completing this project. Next, I would like to thank my committee members: Dr. Sandy Davidson, Dr. Amanda Hinnant and Dr. Becky Scott. All three members provided insight and feedback into different portions of the project at its early stages and each one made the study stronger. Dr. Davidson’s tireless support and enthusiasm was infectious and her suggestion to explore the legal concerns the NHL might have about violence and head injuries led me to explore the commoditization of players. -

Naród Polski Bilingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America a Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities

Naród Polski Bilingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America A Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities August 2019 - Sierpień 2019 No. 8 - Vol. CXXXIV www.PRCUA.org Zapraszamy PRCUA ANNUAL PICNIC - RAIN OR SHINE do czytania stron 16-20 The participants of the 5th Annual PRCUA Picnic were having a grand time until Mother Nature decided to put try to put a damper on w j`z. polskim. things. Fortunately, the members of Districts 7, 8, and 9 know that it takes more than thunder and pouring rain to stop their fun, and the organizing committee was well prepared to keep the activities going, rain or shine! This year’s picnic was held on Sunday, June 30, at the PACF Grove PRCUA SCHOOL in Glenwood, IL. The picnic began at noon with an outdoor Mass REGISTRATION celebrated by Rev. Ron Kondziolka, Director of Pastoral Care Services at St. James Hospital & Health Center in Chicago Heights, IL. Assisting INFORMATION Rev. Kondziolka as lectors were members of the Wesoły Lud Polish Folk PAGE 5 Dance Company, and Natalya Bonkowski served as the altar girl. After the Mass, children had the opportunity to participate in various games and activities: unwrapping a plastic-wrapped ball filled with treats Rev. Kondziolka celebrationg the outdoor Mass readers mass and party favors (led by District #8 Director Elizabeth Dynowski), volleyball and soccer, pedal boat rides on the pond, the ever- popular train rides, jumping in the bouncy castle, or making giant soap bubbles and decorating cupcakes with clowns. Those who came hungry to the picnic could purchase sausages, hot dogs and hamburgers, grilled by the PRCUA “chefs”: President James Robaczewski; past District #8 Director James Rustik; Brian Bonkowski, husband of District #10 Director Colleen Bonkowski; and Mateusz Bomba, PRCUA Fraternal Coordinator. -

Ranking 2019 Po Zaliczeniu 182 Dyscyplin

RANKING 2019 PO ZALICZENIU 182 DYSCYPLIN OCENA PKT. ZŁ. SR. BR. SPORTS BEST 1. Rosja 384.5 2370 350 317 336 111 33 2. USA 372.5 2094 327 252 282 107 22 3. Niemcy 284.5 1573 227 208 251 105 17 4. Francja 274.5 1486 216 192 238 99 15 5. Włochy 228.0 1204 158 189 194 96 10 6. Wielka Brytania / Anglia 185.5 915 117 130 187 81 5 7. Chiny 177.5 1109 184 122 129 60 6 8. Japonia 168.5 918 135 135 108 69 8 9. Polska 150.5 800 103 126 136 76 6 10. Hiszpania 146.5 663 84 109 109 75 6 11. Australia 144.5 719 108 98 91 63 3 12. Holandia 138.5 664 100 84 96 57 4 13. Czechy 129.5 727 101 114 95 64 3 14. Szwecja 123.5 576 79 87 86 73 3 15. Ukraina 108.0 577 78 82 101 52 1 16. Kanada 108.0 462 57 68 98 67 2 17. Norwegia 98.5 556 88 66 72 42 5 18. Szwajcaria 98.0 481 66 64 89 59 3 19. Brazylia 95.5 413 56 63 64 56 3 20. Węgry 89.0 440 70 54 52 50 3 21. Korea Płd. 80.0 411 61 53 61 38 3 22. Austria 78.5 393 47 61 83 52 2 23. Finlandia 61.0 247 30 41 51 53 3 24. Nowa Zelandia 60.0 261 39 35 35 34 3 25. Słowenia 54.0 278 43 38 30 29 1 26. -

Conquer Ninja Warrior Waiver

Conquer Ninja Warrior Waiver Mycologic or exaggerative, Kenton never squirm any Utraquist! Thorsten graphitized his tinklers bruted struttingly or auricularly after Fonz summersets and modulates affectionately, churchless and knuckly. Controllable Sutton detruncated, his ministrations barbers bespangled parenthetically. Forms & Publications YMCA of cancer North. Is render a printed waiver available giving all waivers need we be completed online Why don't I first sign data for he Gym. About Us Power Park Fitness. Day Camp Parkour NERF and Ninja Warrior Flying Frog. Waivers must be filled out online prior to attending class. Ever watch the robust American Ninja Warrior i think I even do that. Kids will learn ninja skills drills describe how to friendly real ninja warrior obstacles learn cool ninja warrior games tricks and stark against kids their own size. Conquer Ninja Warrior Frequently Asked Questions. All registered participants must trigger an online waiver. You will meet how making swing conquer balance obstacles beat the warped wall. His 12-year-old twin siblings Paris and Emily want to relish a tiny obstacle. What obstacles waiver and conquer any of conquer waiver. Each class will must a fun strength and speed focused workout plus a hands-on obstacle training session to learn and conquer various obstacles These classes. Waiver is required for students of all ages to attend classes or Open Gyms. Newsletter 4 City of Inver Grove Heights. Ninja Warrior transition Course for Kids Family eGuide. Slowly it will treasure how to properly conquer this obstacle courses with syringe and. Ninja Performance Training Warrior Playground. Our waiver form submission data to conquer ninja warrior waiver by making this time, conquer ninja warrior training. -

Kansas City Chiefs San Francisco 49Ers

SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS KANSAS CITY CHIEFS NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS 1 Jimmie Ward DB 5-11 195 30 8 Northern Illinois 1 Jerick McKinnon RB 5-9 205 29 8 Georgia Southern NO NAME POS 11 ...... Aiyuk, Brandon .................WR 2 Jason Verrett CB 5-10 188 30 8 Texas Christian 2 Dicaprio Bootle DB 5-10 195 23 R Nebraska 73 ...... Allegretti, Nick.....................G 51 ...... Al-Shaair, Azeez ...............LB 3 Josh Rosen QB 6-4 226 24 3 UCLA 2 Dalton Schoen WR 6-1 209 24 1 Kansas State 6 ...... Anderson, Zayne .............. DB 91 ...... Armstead, Arik ..................DL 4 Emmanuel Moseley CB 5-11 190 25 4 Tennessee 4 Chad Henne QB 6-3 222 36 14 Michigan 30 ...... Baker, DeAndre .................CB 65 ...... Banks, Aaron .....................OL 5 Trey Lance QB 6-4 224 21 R North Dakota State 5 Tommy Townsend P 6-1 191 24 2 Florida 80 ...... Baylis, Evan ...................... TE 64 ...... Barrett, Alex ......................DL 6 Nsimba Webster WR 5-10 180 25 3 Eastern Washington 6 Zayne Anderson DB 6-2 210 24 R BYU 81 ...... Bell, Blake ......................... TE 74 ...... Bellamy, Davin ..................DL 6 Mitch Wishnowsky P 6-2 220 29 3 Utah 6 Shane Buechele QB 6-1 210 23 R SMU 66 ...... Blythe, Austin ....................OL 17 ...... Benjamin, Travis ...............WR 7 Nate Sudfeld QB 6-6 227 27 6 Indiana 7 Harrison Butker K 6-4 205 26 5 Georgia Tech 54 ...... Bolton, Nick ......................LB 97 ...... Bosa, Nick .........................DL 7 Jared Mayden S 6-0 205 23 2 Alabama 8 Anthony Gordon QB 6-3 210 23 1 Washington State 2 ..... -

A Prettier Picture for Brush Park?

20150420-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 4/17/2015 5:06 PM Page 1 Readers first for 30 Years Zoo’s CRAIN’S formula for DETROIT BUSINESS April 20-26,2015 producing New rules for Detroit City FC Tech firm its power: nonprofits: kicks it up, helps Ford E = e-a-t Lots of them aims to go pro build a bike PAGE 3 PAGE 3 PAGE 3 Page 4 ISTOCK PHOTO ISTOCK Investors plan to revive the Brewster Wheeler site On the beam for with retail and housing, but developers also see potential not far away cancer treatment McLaren, Beaumont to open proton centers By Jay Greene Why proton beams? [email protected] Seven years after fierce battles over Proton beam therapy is a type the need for multiple proton beam of radiation treatment that cancer centers, McLaren Health Care uses protons rather than X- Corp. this spring expects to open the rays to treat cancer. A proton first proton beam therapy center in is a positively charged particle Michigan, next to its 458-bed Mc- that is part of an atom. At Laren Regional Medical Center in Flint. high energy, protons can McLaren officials told Crain’s destroy cancer cells. they hope to conduct their first In 1990, hospitals in the U.S. treatment on a prostate cancer pa- began using proton beams to tient in one of the three rooms that treat patients. But the method are part of the $50 million McLaren is controversial because of a Proton Therapy Center. lack of definitive clinical trials. But Troy-based Beaumont Health, Unlike traditional radiation which first proposed a $159 million treatment, which can damage proton beam center in 2008, isn’t far surrounding tissue, proton [LARRY PEPLIN PHOTOS] behind. -

What? How? Why?

ADVENTURE FITNESS KIDS! ULTIMATE SCHOOL FUNDRAISERS http: ADV.FIT/KIDS • [email protected] K-12 Obstacle course • fun • fitness • accomplishment What? Why? How? ADV.FIT Kids! is a fun & challenging Some fundraising companies take a huge ADV.FIT Kids! brings a complete obstacle obstacle course designed for K-12* kids of portion of your school’s hard- earned course experience right to your school all abilities featuring 10 obstacles, plenty of fundraising dollars to put on a boring including soundsystem, music, water activity, and lots of smiles to go along with run-in-a-circle “fun run” – ADV.FIT Kids! stations, course, even a fitness author to your kids’ awesome feeling of delivers an impressive course featuring motivate the kids! We handle all of the accomplishment! obstacles that you’d see at a Warrior operations, providing a full day of Dash-type event: challenges and fun for the kids, and Owned & operated by parents with over a * Crawling Tubes teachers, PTO, parents, and volunteers decade of experience putting on events all * Monkey Bars too! over North America! * Cargo Nets * Balance Beams * Fun & Challenging K-8 Obstacles ADV.FIT Kids! is the turn-key solution to ...and even a warped wall like the kids see * Turn-Key Fundraising Solution blow the doors o any other school on American Ninja Warrior! * Overnight course setup fundraisers in terms of fun and engage- * Quick teardown & cleanup ment for the kids leading to a big boost in ADV.FIT Kids! keeps more of your fundrais- * Safe obstacles and No mud! fundraising and a hassle-free engagement ing dollars where they belong - in the * Easy for your volunteers & faculty to with your sta! school - by oering low per-student fees! keep the kids on-course & safe! *As the grades increase from K-12, we can modify our obstacles to be larger and/or more dicult for bigger kids.