Kenya's Somali North East: Devolution and Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenya Country Office

Kenya Country Office Flood Situation Report Report # 1: 24 November 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers The National Disaster Operations Center (NDOC) estimates that at least 330,000 330,000 people are affected - 18,000 people have been displaced and 120 people affected people have died due to floods and landslides. (NDOC-24/11/2019) A total of 6,821 children have been reached through integrated outreach 31 services and 856 people have received cholera treatment through UNICEF-supported treatment centres. counties affected by flooding (NDOC-24/11/2019) A total of 270 households in Turkana County (out of 400 targeted) and 110 households in Wajir county have received UNICEF family emergency kits 120 (including 20-litre and 10-litre bucket), soap and water treatment tablets people killed from flooding through partnership with the Kenya Red Cross. (NDOC-24/11/2019) UNICEF has reached 55,000 people with WASH supplies consisting of 20- litre jerrycans, 10-litre buckets and multipurpose bar soap. 18,000 UNICEF has completed solarization of two boreholes reaching people displaced approximately 20,500 people with access to safe water in Garissa County. (NDOC-24/11/2019) Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs Kenya has continued to experience enhanced rainfall resulting in flooding since mid-October, negatively impacting the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable populations. According to the National Disaster Operations Center (NDOC) 24 November 2019 updates, major roads have been cut off in 11 counties, affecting accessibility to affected populations for rapid assessments and delivery of humanitarian assistance, especially in parts of West Pokot, Marsabit, Mandera, Turkana, Garissa, Lamu, Mombasa, Tana River, Taita Taveta, Kwale and Wajir Counties. -

Registered Voters Per Constituency for 2017 General Elections

REGISTERED VOTERS PER CONSTITUENCY FOR 2017 GENERAL ELECTIONS COUNTY_ CONST_ NO. OF POLLING COUNTY_NAME CONSTITUENCY_NAME VOTERS CODE CODE STATIONS 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 86,331 136 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 69,307 109 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 126,151 198 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 104,017 165 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 87,326 140 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 107,091 186 002 KWALE 007 MSAMBWENI 68,621 129 002 KWALE 008 LUNGALUNGA 56,948 118 002 KWALE 009 MATUGA 70,366 153 002 KWALE 010 KINANGO 85,106 212 003 KILIFI 011 KILIFI NORTH 101,978 182 003 KILIFI 012 KILIFI SOUTH 84,865 147 003 KILIFI 013 KALOLENI 60,470 123 003 KILIFI 014 RABAI 50,332 93 003 KILIFI 015 GANZE 54,760 132 003 KILIFI 016 MALINDI 87,210 154 003 KILIFI 017 MAGARINI 68,453 157 004 TANA RIVER 018 GARSEN 46,819 113 004 TANA RIVER 019 GALOLE 33,356 93 004 TANA RIVER 020 BURA 38,152 101 005 LAMU 021 LAMU EAST 18,234 45 005 LAMU 022 LAMU WEST 51,542 122 006 TAITA TAVETA 023 TAVETA 34,302 79 006 TAITA TAVETA 024 WUNDANYI 29,911 69 006 TAITA TAVETA 025 MWATATE 39,031 96 006 TAITA TAVETA 026 VOI 52,472 110 007 GARISSA 027 GARISSA TOWNSHIP 54,291 97 007 GARISSA 028 BALAMBALA 20,145 53 007 GARISSA 029 LAGDERA 20,547 46 007 GARISSA 030 DADAAB 25,762 56 007 GARISSA 031 FAFI 19,883 61 007 GARISSA 032 IJARA 22,722 68 008 WAJIR 033 WAJIR NORTH 24,550 76 008 WAJIR 034 WAJIR EAST 26,964 65 008 WAJIR 035 TARBAJ 19,699 50 008 WAJIR 036 WAJIR WEST 27,544 75 008 WAJIR 037 ELDAS 18,676 49 008 WAJIR 038 WAJIR SOUTH 45,469 119 009 MANDERA 039 MANDERA WEST 26,816 58 009 MANDERA 040 BANISSA 18,476 53 009 MANDERA -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) -- Vol. LXVII-No. 52 NAIROBI, 16th November 1965 Price: Sh. 1 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTENoT1cEs-(Contd.) PAGE PAGE The Interpretation and General Provisions Act- The Companies Act-Winding-up Notices . 1392 Temporary Transfers of Powers . 1374 The Trade Unions Act-Registrations . 1392 The Constitution of Kenya (Amendment) Act, 1965- The Societies Act-Registrations, etc. 1393 Authorization . Lost Policies . 1393 The Provident Fund Act-Appointment . Local Government Notices . 1394 The Criminal Procedure Code-Increased Powers . Business Transfer . 1395 Dissolution of Partnership . 1395 The Courts Act-Increased Civil Jurisdictioil . Changes of Name . 1395 The Museums Trustees Act-Appointment . Kenya Stock . 1396 The Agriculture ~ct-~Bnagement Orders, etc. The Trout Act-Appointment . 1396 Lost Local Purchase Orders . 1396 The Agricultural Credit Act-Appointments . The Tea (Appointments to the Board) Regulations- Appointments . SUPPLEMENT No. 88 Bills, 1965 The Medical Practitioners and Dentists Rules- Notice of Election . The Forest Act-Alteration of Boundaries . SUPPLEMENT No. 89 The Borstal Institutions Act-Cancellation, etc. Legislative Supplement LEGALNOTICE NO. PAGE The Local Government Regulations, 1963-Nomination 290-The Iilterpretation and General Provisions Vacancies . Act-Delegation of Powers . 509 291-The Wild Animals Protection (Lake Solai The Registration of Titles Act-Registration . Controlled Area) Notice, 1965 . 509 The Animal Diseases Act-Appointments . 292-The Traffic (Vehicle Licences) (Duration, Fees and Refund) (Amendment) Rules, 1965 Notice re Sale of Game Trophies . 293-The Loca! Government (Kakamega Trade Nairobi Cost of Living Indices . Development Joint Board) Order, 1965 294-The Local Government (Taita-Taveta Trade Notice re Closure of Roads . -

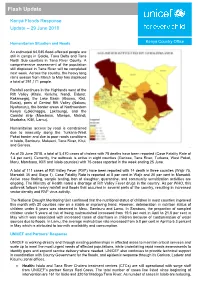

Flash Update

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021

NATIONAL DROUGHT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021 1 Drought indicators Rainfall Performance The month of May 2021 marks the cessation of the Long- Rains over most parts of the country except for the western and Coastal regions according to Kenya Metrological Department. During the month of May 2021, most ASAL counties received over 70 percent of average rainfall except Wajir, Garissa, Kilifi, Lamu, Kwale, Taita Taveta and Tana River that received between 25-50 percent of average amounts of rainfall during the month of May as shown in Figure 1. Spatio-temporal rainfall distribution was generally uneven and poor across the ASAL counties. Figure 1 indicates rainfall performance during the month of May as Figure 1.May Rainfall Performance percentage of long term mean(LTM). Rainfall Forecast According to Kenya Metrological Department (KMD), several parts of the country will be generally dry and sunny during the month of June 2021. Counties in Northwestern Region including Turkana, West Pokot and Samburu are likely to be sunny and dry with occasional rainfall expected from the third week of the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near the long-term average amounts for June. Counties in the Coastal strip including Tana River, Kilifi, Lamu and Kwale will likely receive occasional rainfall that is expected throughout the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be below the long-term average amounts for June. The Highlands East of the Rift Valley counties including Nyeri, Meru, Embu and Tharaka Nithi are expected to experience occasional cool and cloudy Figure 2.Rainfall forecast (overcast skies) conditions with occasional light morning rains/drizzles. -

Kenya Interagency Rapid Assessment Wajir County August

KENYA INTER AGENCY RAPID ASSESSMENT WAJIR COUNTY CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT August 8 – August 25, 2014 Figure 1: Photo taken by KIRA Assessment Team in Gulani village, Wajir County KIRA – Wajir assessment – August 2014 1 1. OVERVIEW OF THE SITUATION AND CRISIS a. Background of the situation Wajir County is divided into 8 districts namely; Wajir East, Tarbaj, Wajir South, Habaswein, Wajir West, Eldas, Buna and Wajir North districts .There are 6 Sub – counties/constituencies currently that is, Tarbaj, Wajir East, Wajir South, Wajir West, Eldas and Wajir North. The current inter-ethnic clashes between the Degodia and Garre communities along Border areas of Mandera and Wajir began on May 13, 2014. There has been an escalation and repeated attacks in Gunana location in Tarbaj Sub – county at the border of the two counties that is in May and June, 2014 and many people were killed in the conflict. This had spillover effects in the entire Wajir County. The inter clan clashes between Garre and Degodia communities along the Wajir – Mandera Border has directly affected 10 locations in Tarbaj District namely; Lehely, Bojigaras, El Kutulo, Mansa, Burmayo, Ogoralle, Berjanai, Dunto, Basaneja and Gunana, as well as Batalu, Danaba, Gulani, Belowle, Bosicha and Ajawa in Wajir North. Similarly, Wagberi in Wajir Central in Wajir East Sub – County has been affected where many houses were torched and vandalized leading to displacement of residents to in El Ado in Wajir South Sub – county and Hodhan in Wajir East with many others displaced into Mandera County. The clashes in Wajir County further affected other areas that are hosting an influx of displaced persons which include Sarman, Elben, Tarbaj and Kutulo in Tarbaj Sub - county, and Waradey in Eldas Sub - county, and Batalu, Danaba, Quadama and Gulani in Wajir North Sub - county. -

Kenya and Somalia Joint Cross Border Health Coordination

KENYA AND SOMALIA JOINT CROSS BORDER HEALTH COORDINATION MEETING REPORT WAJIR PALACE HOTEL, WAJIR-KENYA. APRIL 4-6, 2018 Introduction The Horn of Africa (HOA) Technical Advisory Group (TAG) meetings noted that the risk of significant WPV outbreaks due to evidence of undetected circulation of WPV among the large number of High-Risk Mobile Populations (HRMP) in the HOA region. The TAG stressed the need for active cross-border health coordinations initiatives as a compelling strategy for polio eradication in the region. The objective of the cross-border coordination meetings is to coordinate efforts to strengthen surveillance, routine immunization, and supplemental immunization activities for polio eradication among bordering areas. Specifically, it aims to improve information sharing between countries on polio eradication, identifying and addressing surveillance and immunity gaps in HRMP along the borders, and planning for synchronized supplementary immunization activities along the borders. This report details April 4-6, 2018 meeting in Wajir county (Kenya). The meeting hosted representation from Kenya National MOH, Kenya border Counties MoH officials (Wajir,Turkana and Garissa), Jubaland State (Somalia), WHO representatives (Kenya & Somalia), UNICEF- Kenya, WHO Horn of Africa office, and CORE GROUP Polio Project (CGPP)-HOA Secretariat and CGPP-HOAS partners (American Refugee Committee(ARC), International Rescue Committee (IRC), World Visio- Kenya and Somali Aid. Objectives of the meeting 1. Review on the status of disease surveillance specifically AFP surveillance/VPDs activities. 2. Institutionalize sharing of information modalities between partners in international border regions 3. Discuss the implementation of the joint action plan for cross border collaborations to strengthen cross border disease AFP surveillance & other diseases, e.g. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Beneath the Dryland: Kenya Drought Gender Analysis

Beneath the Dryland Kenya Drought Gender Analysis Oxfam – December 2017 Maria Libertad Mella Dometita, Gender Adviser – Humanitarian Support Personnel Women in Wajir share their stories about how the drought affected their lives. It brought them anguish but at the same time hope, as it presented opportunities to perform new and non-traditional roles. Photo: Maria Libertad Dometita/Oxfam 1 Oxfam Research Reports Oxfam Research Reports are written to share research results, to contribute to public debate and to invite feedback on development and humanitarian policy and practice. They do not necessarily reflect Oxfam policy positions. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of Oxfam. For more information, or to comment on this report, email Maria Libertad Mella Dometita at [email protected]. © Oxfam International December 2017 This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. Email [email protected]. The information in this publication is correct at the time of going to press. Published by Oxfam GB for Oxfam International under ISBN 978-1-78748-154-1 in December 2017. OXFAM Oxfam is an international confederation of 20 organizations networked together in more than 90 countries, as part of a global movement for change, to build a future free from the injustice of poverty. -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum

JOURNAL OF THE EAST AFRICA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY AND NATIONAL MUSEUM 15 October, 1978 Vol. 31 No. 167 A CHECKLIST OF mE SNAKES OF KENYA Stephen Spawls 35 WQodland Rise, Muswell Hill, London NIO, England ABSTRACT Loveridge (1957) lists 161 species and subspecies of snake from East Mrica. Eighty-nine of these belonging to some 41 genera were recorded from Kenya. The new list contains some 106 forms of 46 genera. - Three full species have been deleted from Loveridge's original checklist. Typhlops b. blanfordii has been synonymised with Typhlops I. lineolatus, Typhlops kaimosae has been synonymised with Typhlops angolensis (Roux-Esteve 1974) and Co/uber citeroii has been synonymised with Meizodon semiornatus (Lanza 1963). Of the 20 forms added to the list, 12 are forms collected for the first time in Kenya but occurring outside its political boundaries and one, Atheris desaixi is a new species, the holotype and paratypes being collected within Kenya. There has also been a large number of changes amongst the 89 original species as a result of revisionary systematic studies. This accounts for the other additions to the list. INTRODUCTION The most recent checklist dealing with the snakes of Kenya is Loveridge (1957). Since that date there has been a significant number of developments in the Kenyan herpetological field. This paper intends to update the nomenclature in the part of the checklist that concerns the snakes of Kenya and to extend the list to include all the species now known to occur within the political boundaries of Kenya. It also provides the range of each species within Kenya with specific locality records . -

North Eastern Province (PRE) Trunk Roads ABC Road Description

NORTH EASTERN PROVINCE North Eastern Province (PRE) Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget Box culvert on Rhamu-Mandera B9 6,000,000 A3 (DB Tana River) Garissa - Dadaab - (NB Somali) Nr Liboi 14,018,446 C81 (A3) Modika - (B9) Modogashe 24,187,599 B9 (DB Wajir East) Kutulo - Elwak - Rhamu - (NB Somali) Mandera 11,682,038 Regional Manager Operations of office 4,058,989 Regional Manager RM of Class ABC unpaved structures 725,628 B9 (DB Lagdera) Habaswein - Wajir - (DB Mandera East) Kutulo 31,056,036 C80 (DB Moyale) Korondile - (B9) Wajir 29,803,573 A3 (DB Mwingi) Kalanga Corner- (DB Garissa) Tana River 16,915,640 A3 (DB Mwingi) Kalanga Corner- (DB Garissa) Tana River 90,296,144 North Eastern (PRE) total 228,744,093 GARISSA DISTRICT Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget (DB Garissa) Tana River- Garissa Town 21,000,000 Sub Total 21,000,000 District Roads DRE Garissa District E861 WARABLE-A3-D586 2,250,000.00 R0000 Admin/Gen.exp 302,400.00 URP26 D586(OHIO)-BLOCK 4,995,000.00 Total . forDRE Garissa District 7,547,400.00 Constituency Roads Garissa DRC HQ R0000 Administration/General Exp. 1,530,000.00 Total for Garissa DRC HQ 1,530,000.00 Dujis Const D586 JC81-DB Lagdera 1,776,000.00 E857 SAKA / JUNCTION D586 540,000.00 E858 E861(SANKURI)-C81(NUNO) 300,000.00 E861 WARABLE-A3-D586 9,782,000.00 URP1 A3-DB Fafi 256,000.00 URP23 C81(FUNGICH)-BALIGE 240,000.00 URP24 Labahlo-Jarjara 720,000.00 URP25 kASHA-D586(Ohio)-Dujis 480,000.00 URP26 D586(Ohio)-Block 960,000.00 URP3 C81-ABDI SAMMIT 360,000.00 URP4 MBALAMBALA-NDANYERE 1,056,000.00 Total for Dujis Const 16,470,000.00 Urban Roads Garissa Mun.