J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020. 30(7): 1013–1017 https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2001.01016

Endomicrobial Community Profiles of Two Different Mealybugs: Paracoccus

marginatus and Ferrisia virgata

Polpass Arul Jose1#, Ramasamy Krishnamoorthy1, Pandiyan Indira Gandhi2, Murugaiyan Senthilkumar3, Veeranan Janahiraman1, Karunandham Kumutha1,

- 4

- 4‡

- 1

- 4

- *

- *

Aritra Roy Choudhury , Sandipan Samaddar , Rangasamy Anandham , and Tongmin Sa

1Department of Agricultural Microbiology, Agricultural College and Research Institute, Madurai, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Tamil Nadu, India 2Regional Research Station, Vridhachalam, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Tamil Nadu, India 3Department of Agricultural Microbiology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India 4Department of Environmental and Biological Chemistry, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Republic of Korea

Mealybugs (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha: Pseudococcidae) harbor diverse microbial symbionts that play essential roles in host physiology, ecology, and evolution. In this study we aimed to reveal microbial communities associated with two different mealybugs, papaya mealybug (Paracoccus marginatus) and two-tailed mealybug (Ferrisia virgata) collected from the same host plant. Comparative analysis of microbial communities associated with these mealybugs revealed differences that appear to stem from phylogenetic associations and different nutritional requirements. This first report on both bacterial and fungal communities associated with these mealybugs provides a preliminary insight on factors affecting the endomicrobial communities.

Received: January 13, 2020 Accepted: March 31, 2020

First published online: April 02, 2020

Keywords: Ecology, mealybug, endomicrobiota, phylogeny, Paracoccus marginatus Ferrisia virgata

,

*

Corresponding authors

T.S.

Insects are the most abundant animals in terrestrial ecosystems and are inhabited by symbiotic microbes that provide beneficial services to their hosts [1]. Mealybugs (Homoptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae) are plantsucking scale insects affecting agricultural ecosystems and causing damage to more than 300 plant species [2-4]. Examining the ecological interactions of symbiotic microbes in agriculturally important insect-hosts may lead to novelmethods of pestcontrolandenhancementof agriculturalproductivity [5, 6]. Dietand theinsectlineagehave been proposed to exert different influences on symbiotic microbial diversity [7]. Accordingly, in this study we examined the hypothesis that the mealybug microbial ecology is strongly determined by interaction between phylogenetic constraints and nutritional requirements. To this end, we performed endomicrobial community analysis of two phylogenetically distinct mealybug species that feed concurrently on the same plant yet differ in their choice of feeding site and the processing of the plant-derived diet. 1) Papaya mealybug (PM), Paracoccus marginatus Williams and Granara de Willink, feeds frequently on phloem sap and produces large amounts of honeydew [8]. 2) Two-tailed mealybug (TM), Ferrisia virgata Cockerell, colonizes around the terminal parts of the plant, infrequently accesses the phloem sap and produces small amounts of honeydew [9]. Based on integrated molecular and morphological data, these two mealybugs have been assigned under different sub-families [10]. Pooled PM and TM samples were created from fifty individuals of each mealybug species collected from a papaya (Carica papaya) plant cv. CO8 at Agricultural College and Research Institute, Madurai (9°56'0" N and 78°7'0" E), India. The insects were surface sterilized by rinsing in sterile water, soaking in 70% ethanol and 10% bleach, with three rinses in water, for 60 sec at each step. The surface-sterilized insects were homogenized in liquid nitrogen. Whole DNA was extracted from homogenates using an Insect DNA Purification Kit (Hi-Media, India) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted DNA was amplified using primers targeting the V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene (primers, 341F and 518R) and fungal internal transcribed spacer (primers, ITS5F and ITS2R) [11, 12]. Sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq platform at Genotypic Technology, India. Resulted sequence data were deposited in SRA archives under accession number PRJNA522349. Theraw reads were processed as describedelsewhere[13]. Theprocessing ofrawreadsclustered at 97% identity revealed 5,881 and 2,417 bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs), whereas 258 and 172 fungal OTUs were identified for PM and TM, respectively. The rarefaction curve (Fig. S1) indicated the adequate sampling effort for getting the full extent of taxonomic diversity. It explains how the number of species found in a sampleat any given phylogenetic level is strongly affected by the number of sequences analyzed [14]. The Shannon

Phone: +82-43-261-2561 Fax: +82-43-271-5921 E-mail: [email protected] R.A. E-mail: anandhamranga@gmail. com

#Present address: Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, POB 12, Rehovot 761000, Israel ‡Present address: Department of Land, Air and Water Resources, University of California, Davis, California, USA

Supplementary data for this paper are available on-line only at http://jmb.or.kr.

pISSN 1017-7825 eISSN 1738-8872

Copyright 2020 by

©

The Korean Society for Microbiology and Biotechnology

July 2020 Vol. 30 No. 7

- ⎪

- ⎪

1014

Jose et al.

Table 1. Microbial diversity estimates in the gut of papaya mealybug and two-tailed mealybug.

- Domain Type of mealybug Number of OTUs

- Chao1 (Richness)

- Shannon (Diversity) Simpson (Diversity)

Bacteria

PM

TM PM TM

5881 2417 258

10061.46 4833.76

276

3.42 1.87 1.30 0.54

0.64 0.48 0.91 0.48

Fungi

- 170

- 172

and Simpson diversity indices, and richness estimator (Chao) of bacteria and fungi were relatively higher for PM compared to TM (Table 1). However, the diversity and richness indices of fungi were relatively poor for both the samples compared to the bacterial counterpart. The gut bacterial community had proteobacterial abundance for both of the mealybug species, followed by Actinobacteria and Firmicutes in PM and TM, respectively (Fig. 1A). A previous study of 305 individual insects belonging to 21 taxonomic orders showed that the insect microbiota is dominated by the Proteobacteria and

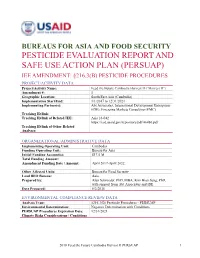

Fig. 1. Bacterial community profile decoded by 16S amplicon-metagenomics. Relative abundance of the gut-

bacterial lineages (after removing endosymbionts) found in PM and TM at (A) phylum level and (B) species level.

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.

- Endomicrobial Communities of Mealybugs

- 1015

Firmicutes [15]. Moreover, the specific abundance of Proteobacteria further correlates well with bacterial communities of different mealybug species [16-18]. Recently, Iasur-Kruh et al. [17]reported that Betaproteobacteria (58%) and Gammaproteobacteria (33%) constituted the proteobacterial community in the vine mealybug. However, this pattern deviated in papaya and two-tailed mealybugs. In papaya mealybug, all the three classes of Proteobacteria (Betaproteobacteria (83.41%), Alphaproteobacteria (7.19%) and Gammaproteobacteria (4.63%) were represented, while Betaproteobacteria is most abundant (97.6%) in two-tailed mealybug (Fig. 1B). At the genus level, PM and TM samples were dominated by the obligate nutritional endosymbionts Tremblaya, which has been reported to provide aid in nutrition and detoxification of plant substances [19, 20]. The ITS sequencebased fungal community analysis revealed the occurrence of seven fungal phyla (Fig. 2A). The majority of sequences were affiliated with Ascomycota (78.75%), followed by Zygomycota (4.74%) and Basidomycota (5.91%). Individually, Ascomycota dominated with 75.28% and 91.65% in PM and TM respectively. The phylum Zygomycota and two different unclassified populations were moderately abundant in PM, while it was less abundant in TM. However, Glomeromycota was more abundant in TM rather than in PM. However, among the classified genera, Cladosporium showed moderate abundance (8.04%), followed by Aureobasidium (5.54%), Mortierella (4.61%). Notably, the majority of Aureobasidium and Mortierella counts were from PM (Fig. 2B). The results of earlier studies using culture-dependent and molecular techniques indicated that vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus, largely harbors Ascomycota [18]. Cladosporium and Mycosphaerella, common environmental fungi, were equally found in both TM and PM. Iasur-Kruh et al. [17] found that Cladosporium is abundant in vine mealybug reared in lab. This suggests that Cladosporium and Mycosphaerella are more transient fungal associates

Fig. 2. Fungal community profile decoded by 18S (ITS) amplicon-metagenomics. Relative abundance of the gut-

fungal lineages (after removing endosymbionts) found in PM and TM at (A) phylum level and (B) species level.

July 2020 Vol. 30 No. 7

- ⎪

- ⎪

1016

Jose et al.

Fig. 3. Functional mapping of the bacterial community associated with PM and TM.

acquired via feeding. A recent study using confocal microscopy revealed that a similar fungus, Beauveria bassiana, penetrates mealybug Phenacoccus manihoti through the legs and mouthparts [21]. Interestingly, several fungal species were found in one mealybug species, while not in the other, though they were sampled from the same plant. For instance, Zygomycota was found in PM, but not in TM. Similarly, Glomeromycota was found in TM, yet it is absent in PM. These differences could be due to selective ecological pressure exerted by the host [18, 22]. Among the symbionts associated with PM and TM, Tremblaya is a well-known endosymbiont of mealybugs. Bacterial communities other than Tremblaya associated with the PM and TM were retrieved from the taxonomy data and mapped for their metabolic activities using differentphenotypic categories in METAGENassist [23]. The analysis was done using the standard settings suggested in the server. The results revealed the occurrence of 15 types of metabolic activities (Fig. 3). Interestingly, abundant bacteria capable of ammonia oxidization, atrazine metabolism, dehalogenation, nitrate reduction, sulfur metabolism, and xylan degradation were found in both mealybug species. The automated metabolic functional mapping of the abundant bacterial community revealed diverse activities, and strongly suggested the role of the bacterial communities associated with both mealybugs in providing nutritional as well as detoxification support to the host insects. For instance, those microbes having the ability to fix and mobilize different nutrients (nitrogen and sulfur) could provide dietary support to the insect host, while others are involved in detoxification of toxic compounds [24]. Difference in the relative abundance of different metabolic functions suggests evolutionary trajectories of the microbial communities, tailored to specific needs of the hosts [24, 25]. Insummary, this study disclosed the endomicrobial communities (bacteria and fungi)intwo mealybug species, P. marg inatus and F. Virgata, differ in phylogenetic and nutritional characteristics. Despite a lack of sequencing replicates, this study provides a preliminary insight into the relationships between different mealybugs and their microbial communities. Differences among the microbial communities appear to be associated largely with their phylogeny and different nutritional characteristics while they fed on the same plant sap. The super dominant bacteria was Tremblaya in both cases, but intra generic diversity was found within this genus in PM. Dynamics of Tremblaya in PM, as well as the moderately abundant and rare species in both mealybug species have to be studied under controlled conditions to reveal their biological and symbiotic roles.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data and analyses from the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The raw reads were deposited in SRA archives and can be accessed by accession number PRJNA522349.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Rapid Grant for Young Investigator (RGYI), Department of Biotechnology

(DBT), Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India under grant no. BT/PR6430/GBD/27/412/ 2012. The authors are so grateful to Prof. Boaz Yuval for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Moran NA, McCutcheonJP, Nakabachi A. 2008. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42: 165-

190.

2. Miller DR, Miller GL. 2002. Redescription of Paracoccus marginatus Williams and Granara de Willink (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae), including descriptions of the immature stages and adult male. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 104: 1-23.

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.

- Endomicrobial Communities of Mealybugs

- 1017

3. Amarasekare KG, Mannion CM, Osborne LS, Epsky ND. 2014. Life history of Paracoccus marginatus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) on four host plant species under laboratory conditions. Environ. Entomol. 37: 630-635.

4. Normark BB, Johnson NA. 2011. Niche explosion. Genetica 139: 551-564. 5. Zindel R, Gottlieb Y, Aebi A. 2011. Arthropod symbioses: a neglected parameter in pest‐and disease‐control programmes. J. Appl.

Ecol. 48: 864-872.

6. Yuval B, Ben-Ami E, Behar A, Ben-Yosef M, Jurkevitch E. 2013. The Mediterranean fruitfly and its bacteria – potential for improving sterile insect technique operations. J. Appl. Entomol. 137: 39-42.

7. Yun JH. 2014. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host.

Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80: 5254-5264.

8. Miller DR, Williams DJ, Hamon AB, 1999. Notes on a new mealybug (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae) pest in Florida and the Caribbean: the papaya mealybug, Paracoccus marginatus Williams and Granara de Willink. Insecta Mundi 13: 179-181

9. Kaydan MB, Gullan J. 2012. A taxonomic revision of the mealybug genus Ferrisia fullaway (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) with descriptions of eight new species and a new genus. Zootaxa 3543: 1.

10. Hardy NB, Gullan PJ, Hodgson CJ. 2008. A subfamily‐level classification of mealybugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) based on integrated molecular and morphological data. Syst. Entomol. 33: 51-71.

11. Whiteley AS, Jenkins S, Waite I, Kresoje N, Payne H, Mullan B, et al. 2012. Microbial 16S rRNA Ion Tag and community metagenome sequencing using the Ion Torrent (PGM) Platform. J. Microbiol. Methods 91: 80-88.

12. Shen Y, Nie J, Li Z, Li H, Wu Y, Dong Y, Zhang J. 2018. Differentiated surface fungal communities at point of harvest on apple fruits from rural and peri-urban orchards. Sci. Rep. 8: 2165.

13. Niu B, Fu L, Sun S, Li W. 2010. Artificial and natural duplicates in pyrosequencing reads of metagenomic data. BMC Bioinformatics

11: 187.

14. Schloss PD, Handelsman J. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 1501-1506.

15. Yun JH. 2014. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host.

Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80: 5254-5264.

16. Gruwell ME, Hardy NB, Gullan PJ, Dittmar K. 2010. Evolutionary relationships among primary endosymbionts of the mealybug subfamily Phenacoccinae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 7521-7525.

17. Iasur-Kruh L, Taha-Salaime L, Robinson WE, Sharon R, Droby S, Perlman SJ, et al. 2015. Microbial associates of the vine mealybug

Planococcus ficus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) under different rearing conditions. Microb. Ecol. 69: 204-214.

18. Ivens AB, Gadau A, Kiers ET, Kronauer DJ. 2018. Can social partnerships influence the microbiome? Insights from ant farmers and their trophobiont mutualists. Mol. Ecol. 27: 1898-1914.

19. Buchner P. 1965. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. pp. 168. USA: Interscience Publishers. (No. QH548 B743) 20. McCutcheon JP, von Dohlen CD. 2011. An interdependent metabolic patchwork in the nested symbiosis of mealybugs. Curr. Biol.

21: 1366-1372.

21. Amnuaykanjanasin A, Jirakkakul J, Panyasiri C, Panyarakkit P, Nounurai P, Chantasingh D. 2013. Infection and colonization of

tissues of the aphid Myzus persicae and cassava mealybug Phenacoccus manihoti by the fungus Beauveria bassiana. BioControl 58:

379-391.

22. Gomez‐Polo P, Ballinger MJ, Lalzar M, Malik A, Ben‐Dov Y, Mozes‐Daube N. 2017. An exceptional family: Ophiocordyceps‐allied fungus dominates the microbiome of soft scale insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccidae). Mol. Ecol. 26: 5855-5868.

23. Arndt D, Xia J, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Guo AC, Cruz JA, et al. 2012. METAGENassist: a comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: W88-W95.

24. Douglas AE. 2009. The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct. Ecol. 23: 38-47. 25. Flórez LV, Biedermann PH, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. 2015. Defensive symbioses of animals with prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 32: 904-936.

July 2020 Vol. 30 No. 7

- ⎪

- ⎪