Jim Baird After the Coup: the Trade Union Delegation to Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Report Card

Congressional Report Card NOTE FROM BRIAN DIXON Senior Vice President for Media POPULATION CONNECTION and Government Relations ACTION FUND 2120 L St NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20037 ou’ll notice that this year’s (202) 332–2200 Y Congressional Report Card (800) 767–1956 has a new format. We’ve grouped [email protected] legislators together based on their popconnectaction.org scores. In recent years, it became twitter.com/popconnect apparent that nearly everyone in facebook.com/popconnectaction Congress had either a 100 percent instagram.com/popconnectaction record, or a zero. That’s what you’ll popconnectaction.org/116thCongress see here, with a tiny number of U.S. Capitol switchboard: (202) 224-3121 exceptions in each house. Calling this number will allow you to We’ve also included information connect directly to the offices of your about some of the candidates senators and representative. that we’ve endorsed in this COVER CARTOON year’s election. It’s a small sample of the truly impressive people we’re Nick Anderson editorial cartoon used with supporting. You can find the entire list at popconnectaction.org/2020- the permission of Nick Anderson, the endorsements. Washington Post Writers Group, and the Cartoonist Group. All rights reserved. One of the candidates you’ll read about is Joe Biden, whom we endorsed prior to his naming Sen. Kamala Harris his running mate. They say that BOARD OF DIRECTORS the first important decision a president makes is choosing a vice president, Donna Crane (Secretary) and in his choice of Sen. Harris, Joe Biden struck gold. Carol Ann Kell (Treasurer) Robert K. -

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20515

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20515 June 14, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House H-232, The Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Madam Speaker: We write today to urge you to fully reopen the House of Representatives. The positive impact of increasing vaccination rates and decreasing cases of COVID-19 are clear to see. Businesses are open, sporting venues and cultural institutions have welcomed back fans and visitors, and restrictions have been lifted. On June 11, Washington D.C. fully reopened and lifted the restrictions put in place to stop the spread of COVID-19. Unfortunately, the United States Capitol and the People’s House have failed to do the same. The Capitol remains closed to the American people and the House continues to maintain policies that run contrary to science of COVID-19. It is time for you to reopen the House and get back to serving the American people. Weekly case numbers in the United States have reached their lowest point since March of 2020 at the very start of the pandemic, and every day hundreds of thousands of Americans are being vaccinated. This also holds true for the Washington D.C. metropolitan area and the Capitol Hill community specifically. Over the last two weeks cases are down 36% in Washington D.C. and over 40% in both Virginia and Maryland. On Capitol Hill, no congressional staffer is known to have tested positive in weeks and no Member of Congress is known to have tested positive in months. This can no doubt be attributed to the institution’s steady access to vaccinations. -

A Rare Campaign for Senate Succession Senate President Pro Tem Sen

V23, N25 Tursday, Feb. 15, 2018 A rare campaign for Senate succession Senate President Pro Tem Sen. Ryan Mishler in Kenley’s appropria- Long’s announcement sets up tions chair, and Sen. Travis Holdman in battle last seen in 2006, 1980 Hershman’s tax and fscal policy chair. By BRIAN A. HOWEY Unlike former House INDIANAPOLIS – The timing of Senate minority leader Scott President Pro Tempore David Long’s retirement Pelath, who wouldn’t announcement, coming even vote on a suc- in the middle of this ses- cessor, Long is likely sion, was the big surprise to play a decisive on Tuesday. But those of role here. As one us who read Statehouse hallway veteran ob- tea leaves, the notion served, “I think Da- that Long would follow vid will play a large his wife, Melissa, into the sunset was a change and positive role in of the guard realization that began to take shape choosing his succes- with Long’s sine die speech last April. sor. That’s a good For just the third time since 1980, this thing in my view. sets up a succession dynamic that will be fasci- He is clear-eyed and nating. Here are several key points to consider: knows fully what is n Long is taking a systemic approach to Senate President Pro Tem David Long said Tuesday, required of anyone reshaping the Senate with the reality that after “No one is indispensible” and “you know when it’s in that role. And ... November, he, Luke Kenley and Brandt Hersh- time to step down. -

2019 Political Contributions

MEPAC Disbursement Political Contributions 2019 Lockheed Martin 2019 LMEPAC Disbursements State Member Party Office District Total ALASKA Lisa Murkowski for US Senate Murkowski, Lisa R U.S. SENATE $2,000.00 True North PAC Sullivan, Daniel R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Sullivan For US Senate Sullivan, Daniel R U.S. SENATE $8,000.00 Alaskans For Don Young Young, Don R U.S. HOUSE AL $5,000.00 ALABAMA RBA PAC (Reaching for Brighter America) Aderholt, Robert R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Aderholt for Congress Aderholt, Robert R U.S. HOUSE 4 $6,000.00 Mo Brooks for Congress Brooks, Mo R U.S. HOUSE 5 $6,000.00 Byrne For Congress Byrne, Bradley R U.S. HOUSE 1 $5,000.00 Seeking Justice Committee Jones, Doug D Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Doug Jones For Senate Jones, Doug D U.S. SENATE $9,000.00 Gary Palmer For Congress Palmer, Gary R U.S. HOUSE 6 $1,000.00 MARTHA PAC Roby, Martha R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Martha Roby For Congress Roby, Martha R U.S. HOUSE 2 $4,000.00 American Security PAC Rogers, Mike R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Mike Rogers For Congress Rogers, Mike R U.S. HOUSE 3 $9,000.00 Terri PAC Sewell, Terri D Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Terri Sewell For Congress Sewell, Terri D U.S. HOUSE 7 $4,000.00 Defend America PAC Shelby, Richard R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 ARKANSAS Arkansas for Leadership PAC Boozman, John R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Cotton For Senate Cotton, Tom R U.S. -

This Was an Historic Election. a Record Number of People Voted and Became Politically Active for the First Time

This was an historic election. A record number of people voted and became politically active for the first time. Thanks to your support, we elected Joe Biden and helped to re-elect many JAC candidates who will work side-by-side with the Biden administration towards our common goals. Although not all the election results were what we hoped for, together we took an important step to save our democracy. Despite the pandemic, JAC stayed very busy during this election season. Our members sent out more than 40,000 postcards, phoned and texted voters in key battleground races. JAC was able to offer you, via Zoom, meetings with candidates and leading policy experts. Through your generosity, JAC was involved in more than 110 races across the country. We are sending two new Senators to Washington. Hopefully, after the special runoff election in Georgia on January 5th, we will be sending two more members — Jon Ossoff and Rev. Raphael Warnock — to the Senate as well. These are must-win races if we ever hope to remove the gavel from Mitch McConnell’s hands and implement Joe Biden’s agenda. We hope we can count on you to step up one more time. These past four years have proven that elections have consequences. You can donate to Jon’s campaign or Rev. Warnock’s campaign. Click here to find out other ways to get involved and turn Georgia blue. Many races this year were decided by razor thin margins, proving clearly that every vote does count. As of press time, there were still several uncalled Congressional races. -

Veterans Elected in the Midterms 2018

Veterans Elected In the Mid-Terms to Congress As of 16 November 2018, here are the veterans from all services who were just recently elected or re- elected to Congress. This may not be completely accurate since some races are too close to call. However, having said that if one or more of these Members of Congress are in your AOR, I request that you pass this along to our membership so that they can reach out to the newly elected veterans to put our Marine Corps League on the radar and to establish a constituent relationship. We also need to reaffirm our relationships with the incumbents as 2019 is going to be a busy legislative time with some new political dynamics. Note that there are 11 Marines in the new Congress. Here’s the list divided up between those who ran as Republicans and Democrats: Republicans 1. Rep. Don Young (R-Alaska) Branch: Army 2. Rep. Rick Crawford (R-Ariz.) Branch: Army 3. Rep. Steve Womack (R-Ariz.) Branch: Army National Guard 4. Rep. Paul Cook (R-Calif.) Branch: Marine Corps 5. Rep. Duncan Hunter (R-Calif.) Branch: Marine Corps 6. Rep. Neal Dunn (R-Fla.) Branch: Army 7. Rep.-elect Michael Waltz (R-Fla.) Branch: Army 8. Rep. Vern Buchanan (R-Fla.) Branch: Air Force National Guard 9. Rep.-elect Greg Steube (R-Fla.) Branch: Army 10. Rep. Brian Mast (R-Fla.) Branch: Army 11. Rep. Doug Collins (R-Ga.) Branch: Still serving in the Air Force Reserve 12. Rep. Barry Loudermilk (R-Ga.) Branch: Air Force 13. -

List of Government Officials (May 2020)

Updated 12/07/2020 GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS PRESIDENT President Donald John Trump VICE PRESIDENT Vice President Michael Richard Pence HEADS OF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTS Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar II Attorney General William Barr Secretary of Interior David Bernhardt Secretary of Energy Danny Ray Brouillette Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Benjamin Carson Sr. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao Secretary of Education Elisabeth DeVos (Acting) Secretary of Defense Christopher D. Miller Secretary of Treasury Steven Mnuchin Secretary of Agriculture George “Sonny” Perdue III Secretary of State Michael Pompeo Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross Jr. Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie Jr. (Acting) Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolf MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Ralph Abraham Jr. Alma Adams Robert Aderholt Peter Aguilar Andrew Lamar Alexander Jr. Richard “Rick” Allen Colin Allred Justin Amash Mark Amodei Kelly Armstrong Jodey Arrington Cynthia “Cindy” Axne Brian Babin Donald Bacon James “Jim” Baird William Troy Balderson Tammy Baldwin James “Jim” Edward Banks Garland Hale “Andy” Barr Nanette Barragán John Barrasso III Karen Bass Joyce Beatty Michael Bennet Amerish Babulal “Ami” Bera John Warren “Jack” Bergman Donald Sternoff Beyer Jr. Andrew Steven “Andy” Biggs Gus M. Bilirakis James Daniel Bishop Robert Bishop Sanford Bishop Jr. Marsha Blackburn Earl Blumenauer Richard Blumenthal Roy Blunt Lisa Blunt Rochester Suzanne Bonamici Cory Booker John Boozman Michael Bost Brendan Boyle Kevin Brady Michael K. Braun Anthony Brindisi Morris Jackson “Mo” Brooks Jr. Susan Brooks Anthony G. Brown Sherrod Brown Julia Brownley Vernon G. Buchanan Kenneth Buck Larry Bucshon Theodore “Ted” Budd Timothy Burchett Michael C. -

Report of Receipts and Disbursements

04/15/2020 17 : 43 Image# 202004159219264420 PAGE 1 / 35 REPORT OF RECEIPTS FEC AND DISBURSEMENTS FORM 3 For An Authorized Committee Office Use Only 1. NAME OF TYPE OR PRINT Example: If typing, type COMMITTEE (in full) over the lines. 12FE4M5 ELECT JIM BAIRD FOR CONGRESS P.O. BOX 203 ADDRESS (number and street) Check if different than previously GREENCASTLE IN 46135 reported. (ACC) CITY STATE ZIP CODE 2. FEC IDENTIFICATION NUMBER STATE DISTRICT C C00662940 3. IS THIS ✘ NEW AMENDED REPORT (N) OR (A) IN 04 4. TYPE OF REPORT (Choose One) (b) 12-Day PRE-Election Report for the: (a) Quarterly Reports: Primary (12P) General (12G) Runoff (12R) ✘ April 15 Quarterly Report (Q1) Convention (12C) Special (12S) July 15 Quarterly Report (Q2) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the October 15 Quarterly Report (Q3) Election on State of January 31 Year-End Report (YE) (c) 30-Day POST-Election Report for the: General (30G) Runoff (30R) Special (30S) Termination Report (TER) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the Election on State of M M / D D / Y Y Y Y M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 5. Covering Period 01 2020 through 03 31 2020 I certify that I have examined this Report and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct and complete. BAIRD, JAMES, R, Dr., Type or Print Name of Treasurer BAIRD, JAMES, R, Dr., M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 04 15 2020 Signature of Treasurer [Electronically Filed] Date NOTE: Submission of false, erroneous, or incomplete information may subject the person signing this Report to the penalties of 52 U.S.C. -

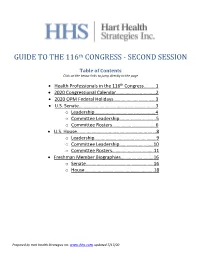

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

1H 2020 Contributions

7/30/2020 Lobbying Contribution Report L C R Clerk of the House of Representatives • Legislative Resource Center • B-106 Cannon Building • Washington, DC 20515 Secretary of the Senate • Office of Public Records • 232 Hart Building • Washington, DC 20510 1. F T N 2. I N Type: House Registrant ID: Organization Lobbyist 30230 Organization Name: Senate Registrant ID: EXXON MOBIL CORP 14017 3. R P 4. C I Year: Contact Name: 2020 Ms.Courtney S. Walker Mid-Year (January 1 - June 30) Email: Year-End (July 1 - December 31) [email protected] Amendment Phone: 9729406000 Address: 5959 LAS COLINAS BLVD. IRVING, TX 75039 USA 5. P A C N EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (EXXONMOBIL PAC) 6. C No Contributions #1. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION POLITICAL $5,000.00 01/28/2020 ACTION COMMITTEE (EXXONMOBIL PAC) Payee: Honoree: TEAM HAGERTY BILL HAGERTY, CANDIDATE, U.S. SENATE #2. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION POLITICAL $2,000.00 01/28/2020 ACTION COMMITTEE (EXXONMOBIL PAC) Payee: Honoree: BISHOP FOR CONGRESS REP. JAMES DANIEL BISHOP #3. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION POLITICAL $2,500.00 01/28/2020 ACTION COMMITTEE (EXXONMOBIL PAC) Payee: Honoree: MICHAEL BURGESS FOR REP. MICHAEL C. BURGESS CONGRESS https://lda.congress.gov/LC/forms/ReportDisplay.aspx 1/22 7/30/2020 Lobbying Contribution Report #4. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION POLITICAL $2,500.00 01/28/2020 ACTION COMMITTEE (EXXONMOBIL PAC) Payee: Honoree: CAPITO FOR WEST VIRGINIA SEN. -

Indiana Legislators from Your Hometown

Indiana Legislators from Your Hometown Lloyd Arnold Years Served: 2012 - present Chamber(s): House County(s): Dubois, Spencer, Perry, Crawford, and Orange District: 74 Party: Republican Profession(s): Executive Director of Economic Development in Orange County Education: Oakland City University: Business Management Committees: Natural Resources (Vice chair), Agriculture and Rural Development, Elections, and Apportionment, Veterans Affairs and Public Safety Rep. Lloyd Arnold has been a resident of District 74 his entire life and is a member of the 118th General Assembly freshman class. He was raised in Crawford County and now raises a family there with his wife, Jody, a Perry County native. Rep. Arnold graduated from Perry Central High School in 1992, where his father taught. After graduation, Rep. Arnold went on to join the U.S. Army and later joined the Indiana National Guard. During his service in the National Guard, he attended Oakland City University where he studied Business Management and earned a commission as an officer. Rep. Arnold was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1998, and in 2003 he served the Indiana National Guard in Iraq as an executive officer. Rep. Arnold has also served eight years as a reserve sheriff’s deputy in District 74, and now serves on the Crawford County Sheriff’s Department Merit Board. During his service in the National Guard, Rep. Arnold was employed by Toyota in Princeton as part of the Quality Management Team. Using the experience gained from that position, Rep. Arnold made the decision to open his own businesses in 2007. While serving in the Statehouse, Rep. Arnold sold his business and is now helping entrepreneurs succeed as the executive director of Orange County Economic Development Partnership. -

Representative Buddy Carter (R-GA-1)

Representative Buddy Carter (R-GA-1) Earl L. “Buddy” Carter is an experienced businessman, health care professional and faithful public servant. As the owner of Carter’s Pharmacy, Inc., South Georgians have trusted Buddy with their most valuable assets: their health, lives and families for more than thirty years. While running his business, he learned how to balance a budget and create jobs. He also saw firsthand the devastating impacts of government overregulation which drives his commitment to ensuring that the federal government creates policies to empower business instead of increasing burdens on America’s job creators. A committed public servant, Buddy previously served as the Mayor of Pooler, Georgia and in the Georgia General Assembly where he used his business experience to make government more efficient and responsive to the people. As the only pharmacist serving in Congress, Buddy is the co-chair of the Community Pharmacy Caucus and is dedicated to working towards a health care system that provides more choices, less costs and better services. A lifelong resident of the First District, Buddy was born and raised in Port Wentworth, Georgia and is a proud graduate of Young Harris College and the University of Georgia where he earned his Bachelor of Science in Pharmacy. Buddy married his college sweetheart, Amy, 40 years ago. Buddy and Amy now reside in Pooler, Georgia and have three sons, two daughters-in-law and four grandchildren. Date of Birth: September 6, 1957 Year Elected to Seat: 2015 Education: University of Georgia Committees Assignments: • Energy and Commerce Notes: Biographical information derived from the Congressional website of the legislator referenced above.