6. Activist Scholarship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Performance-Conscious Activism

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Performance -conscious Activism and Activist -conscious Performance as Discourse in the Aftermath of the Los Angeles Rebellion of 1992 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS For the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Performance Studies By Kamran Afary EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2007 2 © Copyright by Kamran Afary 2007 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Performance -conscious Activism and Activist -conscious Performance as Discourse in the Aftermath of the Los Angeles Rebellion of 1992 Kamran Afary This dissertation deploys an interdisciplinary methodology, extending what is conventionally understood as discourse to include performance. It brings together the fields of performance stud ies, discourse analysis and theatre studies to document, contextualize, and analyze the events after the Los Angeles rebellion of 1992. It examines gang youth who turned to community activism to help maintain truce between former warring gangs; small comm unity - based organizations of mothers who worked to defend their incarcerated sons; and a variety of other groups that organized demonstrations, meetings, and gatherings to publicize the community’s opposition to brutal police practices, unjust court proced ures, and degrading media images. The dissertation also addresses the intersections between grassroots activism and the celebrated performance and video Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 by Anna Deavere Smith™. Together, activists and performers developed new counter -public spaces and compelling counter -narratives that confronted the extremely negative media representations of the Los Angeles rebellion. In these spaces and narratives, t he activists/performers nurtured and developed their oppositional identities and interests, often despite dire economic conditions and social dislocations. -

Culture Within and Culture About Crime: the Case of the “Rodney

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Culture within and culture about crime: The case of the "Rodney King Riots" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b7123xz Journal CRIME MEDIA CULTURE, 12(2) ISSN 1741-6590 Author Katz, Jack Publication Date 2016-08-01 DOI 10.1177/1741659016641721 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CMC0010.1177/1741659016641721Crime, Media, CultureKatz 641721research-article2016 Article Crime Media Culture 1 –19 Culture within and culture © The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: about crime: The case of the sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1741659016641721 “Rodney King Riots” cmc.sagepub.com Jack Katz UCLA, USA Abstract Does cultural criminology have a distinct intellectual mission? How might it be defined? I suggest analyzing three levels of social interaction. At the first level, the culture of crime used by those committing crimes and the process of creating representations of crime in the news, entertainment products, and political position statements proceed independently. At the second level, there is asymmetrical interaction between those creating images of crime and those committing crime: offenders use media images to create crime, but cultural representations of crime in the news, official statistics, and entertainment are developed without drawing on what offenders do when they commit crime, or vice versa. At a third level, we can find symmetrical, recursive interactions between the cultures used to do crime and cultures created by media, popular culture, and political expressions about crime. Using the “Rodney King Riots” as an example, I illustrate the looping interactions through which actors on the streets, law enforcement officials, and politicians and news media workers, by taking into account each other’s past and likely responses, develop an episode of anarchy through multiple identifiable stages and transformational contingencies. -

Crack in Los Angeles: Crisis, Militarization, and Black Response to the Late Twentieth-Century War on Drugs

Crack in Los Angeles: Crisis, Militarization, and Black Response to the Late Twentieth-Century War on Drugs Donna Murch In the winter of 1985 the Los Angeles Police Department (lapd) unveiled a signature Downloaded from new weapon in the city’s drug war. With Chief Daryl F. Gates copiloting, the Special Weapons and Tactics Team (swat) used a fourteen-foot battering ram attached to an “ar- mored vehicle” to break into a house in Pacoima. After tearing a “gaping hole” in one of the outside walls of the house, police found two women and three children inside, eating ice cream. swat uncovered negligible quantities of illicit drugs, and the district attorney http://jah.oxfordjournals.org/ subsequently declined to prosecute. In the days following the raid, black clergy and the San Fernando Valley chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (naacp) organized a protest rally in a local church. “We don’t need new weapons to be tried out on us,” Rev. Jefrey Joseph exclaimed. “Of all the methods that there are to ar- rest a person, they used a brand new toy.” Not all members of the African American com- munity agreed, however. City councilman David Cunningham, who represented South Los Angeles, praised Gates’s actions. “Go right ahead, Chief. You do whatever you can to by guest on September 1, 2015 get rid of these rock houses. Tey’re going to destroy the black community if you don’t.”1 Tese divergent responses embody the core contradiction produced by crack cocaine and the war on drugs for African American communities of Los Angeles in the 1980s. -

Using RICO As a Remedy for Police Misconduct

Florida State University Law Review Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 7 2003 Leaving No Stone Unturned: Using RICO as a Remedy for Police Misconduct Michael Rowan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Rowan, Leaving No Stone Unturned: Using RICO as a Remedy for Police Misconduct, 31 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2003) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol31/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW LEAVING NO STONE UNTURNED: USING RICO AS A REMEDY FOR POLICE MISCONDUCT Michael Rowan VOLUME 31 FALL 2003 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Michael Rowan, Leaving No Stone Unturned: Using RICO as a Remedy for Police Misconduct, 31 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 231 (2003). LEAVING NO STONE UNTURNED: USING RICO AS A REMEDY FOR POLICE MISCONDUCT MICHAEL ROWAN* I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 232 II. IT’S ALIVE!: THE EVOLUTION OF CIVIL RICO AND WHETHER ITS APPLICATION TO THE LAPD IS A LOGICAL NEXT STEP.............................................................. 239 A. The Evolution of a Monster .......................................................................... 240 B. In the Monster’s Sights: The LAPD As a Logical Next Step in RICO’s Evolution? -

The Hunt for Red Menace, Full Report

The Hunt for Red Menace The Hunt for Red Menace: How Government Intelligence Agencies & Private Right-Wing Groups Target Dissidents & Leftists as Subversive Terrorists & Outlaws by Chip Berlet Political Research Associates Revised 19941 ”Our First Amendment was a bold effort. .to establish a country with no legal restrictions of any kind upon the subjects people could investigate, discuss, and deny. The Framers knew, better perhaps than we do today, the risks they were taking. They knew that free speech might be the friend of change and revolution. But they also knew that it is always the deadliest enemy of tyranny.” -U. S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black Since the colonial period in the late 1690s liberties for illusionary national security our land has been swept by witch hunts, moral safeguards. Some observers of this phenomenon panics, and fears of collectivist plots. Following see it as having fueled Cold War antagonisms the end of World War II, a coalition of and resulted in what they term the “National conservative, ultra-conservative, right-wing and Security State.” liberal anti- communist political movements and Within the United States there developed a groups organized support for high levels of covert apparatus to suuport domestic anti- military spending, promoted the use of covert communism in the form of a loosely-knit action abroad, and cultivated the acceptance of infrastructure where both public and private obsessive governmental secrecy, surveillance intelligence agents and right-wing ideologues and repression at home. In the domestic public shared information both formally and sphere this coalition shaped an overwhelming informally. The result was an ad-hoc domestic willingness among citizens to trade real civil counter-subversion network. -

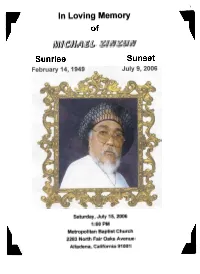

Memory of Michael Zinzun

1 Saturday, July 15,2006 1 :00 PM Metropolitan Baptist Church 2283 North Fair Oaks Avenue Altadena, California 91001 2 ~ ~ ( ~ Obituary Michael Zinzun was born February 14, 1949 in Chicago lllinois. He was the second child born to Michael and Jean Zinzw1. Michael migrated to Oakland. Califon:ria in 1959 where he resided widl his cousin Cmmen Collins ID1tilhis Mom and eight brodlers and sisters atrived. Michael attendedLight House Full Gospel Church Pastoredby Matthew A. Jone~ where he received his spiritual foundation. Michael always respectedand highly esteemedElder Jones and his teachjngs. Michael attended Lincoln elementary. McKinley Jr. High and fmished High School at Blair High. Upon completing school, Michael set out to conquer the world Michael had dreams and he knew at an early age that he was destined for greatness,born to lead, and organize. Several years later Michael enrolled'm LA Tech and upon gyoduating,he became a certified Auto Mechanic. Shortly thereafter, Michael opened his own Automotive shop located m Altadena, California where he enjoyed repairing every kmd of car you could imagine. However, this was not enough for Mike, after bemg there at the shop, he began to befriend several of the yO1.D1gmen m the neighborhood, and before you knew it they were hanging out m the shop learning how to repair cars. This went on for several years. Michael began to hunger for more. so he closed shop and set out to researchand study other areasof concern. He became an active member of the world renown Black Panther Party for Self Defense.he was an organizer of the Free Breakfast. -

Guatemala CIA's Ass Urder Inc

soe No. 621 ~X.623 21 April 1995 13,000 Bus Drivers Fired exico Cily: Union-Busling al Gunpoinl APRIL 17-0n April 8, the government of Mexico City declared the capital's publicly owned bus com pany, Ruta 100, "bankrupt." This left 3 million daily riders without transport, most of them from outlying working-class colonias (neighborhoods) of the Fed eral District (DF) and the state of Mexico. Simulta neously, the government fired all of Ruta 1000s nearly 13,000 workers, who are organized in the independent SUTAUR-100 union. To replace them, the DF brought in cops to operate rented buses and drastically slashed the number of routes. To enforce this vicious attack, hundreds of heavily armed security police cordoned off Ruta 100 bus barns, maintenance depots and the union's head quarters. Warrants were issued for a dozen union lead ers on trumped-up charges of corruption and "breach of trust." Ricardo Barco, one of the founders of SUTAUR and its legal adviser, was surrounded by 60 submachine-gun toting police as he came out of a Sanborn's restaurant and beaten into unconscious ness. Six of the union leaders are presently behind bars, and union funds have been frozen. Meanwhile, bail has been set at 10 million new pesos (US$I.5 million) per person! Mexican and U.S. labor must demand: Release the arrested SUTAUR leaders Drop the charges! Stop the destruction of Ruta 100! The firings and arrests have been met with defiance. When the government offered to "re-hire" fired driv ers and maintenance mechanics, almost none accepted the offer. -

Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship

Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship Edited by Charles R. Hale Published in association with University of California Press Description: Scholars in many fields increasingly find themselves caught between the academy, with its demands for rigor and objectivity, and direct engagement in social activism. Some advocate on behalf of the communities they study; others incorporate the knowledge and leadership of their informants directly into the process of knowledge production. What ethical, political, and practical tensions arise in the course of such work? In this wide-ranging and multidisciplinary volume, leading scholar-activists map the terrain on which political engagement and academic rigor meet. Editor: Charles R. Hale is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin. Contributors: Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Edmund T. Gordon, Davydd J. Greenwood, Joy James, Peter Nien-chu Kiang, George Lipsitz, Samuel Martínez, Jennifer Bickham Mendez, Dani Nabudere, Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Jemima Pierre, Laura Pulido, Shannon Speed, Shirley Suet-ling Tang, João H. Costa Vargas Review: “The contributors to this project seek a social science that continually renews itself through direct engagement with practical problems and efforts to create a better world. They wish to overcome tendencies to reproduce existing frameworks of knowledge in “ivory tower” settings cut off from practical human concerns. And they encourage collaboration with nonacademics who are also actively engaged in the development -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO From

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO From Southern California to Southern Africa: Translocal Black Internationalism in Los Angeles and San Diego from Civil Rights to Antiapartheid, 1960 to 1994 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Mychal Matsemela-Ali Odom Committee in Charge: Professor Luis Alvarez, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Widener, Co-Chair Professor Dennis R. Childs Professor Jessica L. Graham Professor Jeremy Prestholdt 2017 © Mychal Matsemela-Ali Odom, 2017 All Rights Reserved. The Dissertation of Mychal Matsemela-Ali Odom is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my ancestors, family, and elders who made this study possible. This is dedicated to my ancestors beginning with Manch Kessee, the rebel enslaved African whose spirit lives in all his descendants. To Daphne Belgrave Kersee, Manch H. Kersee, Sr., Felton Andrew Odom, and Nadine Odom. It is dedicated to my parents Michael Andrew Odom and Maria Odell Kersee-Odom. This is for my wife Michelle Rowe-Odom and our children: Mayasa-Aliyah Estina Odom and Malika-Akilah Maria Odom. It is in honor of my siblings, Mosi Tamara Rashida Odom and Matthieu Renell Clayton Jackson; as well as your children, Jeremiah Harris, Makhia Jackson, and Josiah Harris. It is also dedicated to all members of the Odom, Kersee, Belgrave, Joseph, and Rowe families. As well, this is dedicated to the lives lost from state murder during the composition of this study: Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Alfred Olango and the many others. -

Black Panther, Michael Zinzun, Remembered

$2 A B C F U P D A T E Q UA R T E R L Y P U B L I C AT I O N O F T H E A B C F Fall 2006 "Any movement that does not support their political internees is a sham movement." - O. Lutalo Issue #45 Black Panther, Michael Zinzun, Remembered Also in this Update: Campaign for the Virgin Island 5 • Sinn Fein Snitch Found Dead • Update on Cuban 5 • Rod Coronado Arrest • Update on McGowen Case • Josh Wolf Jailed Again • Statement by Seth Hayes on Parole Denial • Peltier's Statement on Ireland Hunger Strike, 81 • Omaha 2 Update • “You Call this Democracy” by Ojore Lutalo • Personal Appeal by Jaan Laaman • Former Irish POW Arrested in So Cal • And Much More In the 80s,however, the ABC began to gain W H AT IS THE ANARCHIST BLACK CROSS FEDERAT I O N ? popularity again in the US and Europe. For years, the A B C ’s name was kept alive by a The Anarchist Black Cross (ABC) began provide support to those who were suff e r i n g number of completely autonomous groups shortly after the 1905 Russian Revolution. It because of their political beliefs. scattered throughout the globe and support- formed after breaking from the Political Red In 1919, the org a n i z a t i o n ’s name changed ing a wide variety of prison issues. Cross, due to the group’s refusal to support to the Anarchist Black Cross to avoid confu- In May of 1995, a small group of A B C Anarchist and Social Revolutionary Political sion with the International Red Cross. -

79 Overview.PM

Issue Overview 1 Overview of “Race, Class, and State Crime” Editors IDNEY L. HARRING’S “THE DIALLO VERDICT: ANOTHER ‘TRAGIC ACCIDENT’ IN NEW York’s War on Street Crime?” challenges the premise that excessive Spolice violence is the price we must pay to improve the quality of urban life. He argues that Amadou Diallo’s shooting death resulted from aggressive and racist police practices, deeply rooted in current New York police policy. Such practices led to the killing of four unarmed black men in 13 months. The article describes the brutal circumstances of the police shooting and the mishandling of the trial, which legally justified New York’s aggressive policing policy by concluding that the killing of Diallo was an “accident,” an unavoidable conse- quence of good police work. Harring examines how tactical squads, like the one that killed Diallo, routinely violate the Fourth Amendment and the civil rights of the victims of the searches. Such illegal searches (rousts) for guns or contraband drugs in “high-crime areas” generate the daily statistics that make both the squad and the precinct look good under the “comstat” computer-based police account- ability programs that structure police management in New York and many other cities. Most chilling to Harring is that although most New York political forces bemoan these deaths as tragic, they consider the violent practices leading to them to be acceptable policing. In contrast, these forces distanced themselves from the officers involved in the police torture of Abner Louima, and even most New York police officers abandoned their support for them. -

Black Panther Party Volume 16, Number 2 Suggested Donation $2.00 October 2006

r- ':.. ,· tt l- ~1 - ~-allllll!!!!lllt'lll\n -- ~1111!1!!!!!! -- amAn I ~ - Published by the Commemoration Committee for the.Black Panther Party Volume 16, Number 2 Suggested Donation $2.00 October 2006 40th Annivenarv commemoratiOn I of the 111011 P111111r P1r1v · · A time to reaffirm a cadre commitment to the Ten-Point Program By Melvin Dickson m which we build the IO-Point ~ ~ With workshops, presentations, Program and bring revolutionary § book-signings, and other events intercoinmunalism to life in our own throughout the month of October, for land and hemisphere as a primary aim. mer Black Panther Party members, Some of us in the BPP were families and friends from all parts of "cadre." Many of the younger genera the country and the world will cele tion may not know what that term rep brate and commemorate the 40th resents - those of us who do must Anniversary of the founding of the teach its meaning, and the necessity Black Panther Party (BPP), centered for cadre-based, professional practice in , Oakland, California_ People will . to successfully overcome, through visit Black _Panther historical sites in organization, the problems encircling West Oakland, North Oakland, East our class and the struggle today. Oakland as well as South Berkeley On this 40th Anniversary of its and Richmond, where the vati-ous BPP founding by Huey · P. Newton and headquarters, branches and facilities Bobby Seale, we are commemorating began. Farmer members will take pic the heroism and victories of the Black tures together at the Alameda County Panther Party. As we honor the heroes· court building where, 38 years ago, and soldiers of the movement, both the-Free Huey Movement set the polit living and dead; as we pay tribute to ical passions of the black community the nobility of principle and dignity of and the country on fire.