Subterranean Journeys March 2017 a Springfield Plateau Grotto Publication Volume 12 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

Springfield Area Directory of Environmental Agencies and Organizations

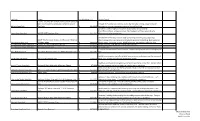

Springfield Area Directory of Environmental Agencies and Organizations Springfield/Greene County Choose Environmental Excellence 2010 Welcome to the Springfield Area Directory of Environmental Agencies and Organizations… …The purpose of this directory is to provide information about government agencies, not-for-profit and member-based organizations serving Springfield and Greene County that are active in protecting our natural environment. The directory has been compiled by Springfield/Greene County Choose Environmental Excellence as a service to the community. The directory will be periodically updated to include new submissions as they are received. In addition to providing contact information for several environmental agencies and organizations, each listing in the directory also provides information that will allow the user to determine which agency or organization will best meet a particular need. Additions to the Directory, as well as suggestions for improvement, can be made by submitting information to: Barbara J. Lucks Springfield/Greene County Choose Environmental Excellence PO Box 8368 Springfield, MO 65801 Re: Springfield Environmental Directory Or send an e-mail to: [email protected] This directory is also available on the following web sites: www.springfieldmo.gov/cee www.OzarksEnvironment.com i Table of Contents Introduction to the Directory i Table of Contents ii U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 1 U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS) 2 MO Dept. of Conservation (MDC) – Nature Center 3 MO Dept. of Conservation (MDC) – Service Center 4 MO Dept. of Conservation (MDC) – Storm Drain Stenciling Project 5 MO Dept. of Natural Resources (MDNR) – Air Pollution Control 6 MO Dept. of Natural Resources (MDNR) – Hazardous Waste Management 7 MO Dept. -

Meramec River Watershed Demonstration Project

MERAMEC RIVER WATERSHED DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Funded by: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency prepared by: Todd J. Blanc Fisheries Biologist Missouri Department of Conservation Sullivan, Missouri and Mark Caldwell and Michelle Hawks Fisheries GIS Specialist and GIS Analyst Missouri Department of Conservation Columbia, Missouri November 1998 Contributors include: Andrew Austin, Ronald Burke, George Kromrey, Kevin Meneau, Michael Smith, John Stanovick, Richard Wehnes Reviewers and other contributors include: Sue Bruenderman, Kenda Flores, Marlyn Miller, Robert Pulliam, Lynn Schrader, William Turner, Kevin Richards, Matt Winston For additional information contact East Central Regional Fisheries Staff P.O. Box 248 Sullivan, MO 63080 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Overview The overall purpose of the Meramec River Watershed Demonstration Project is to bring together relevant information about the Meramec River basin and evaluate the status of the stream, watershed, and wetland resource base. The project has three primary objectives, which have been met. The objectives are: 1) Prepare an inventory of the Meramec River basin to provide background information about past and present conditions. 2) Facilitate the reduction of riparian wetland losses through identification of priority areas for protection and management. 3) Identify potential partners and programs to assist citizens in selecting approaches to the management of the Meramec River system. These objectives are dealt with in the following sections titled Inventory, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analyses, and Action Plan. Inventory The Meramec River basin is located in east central Missouri in Crawford, Dent, Franklin, Iron, Jefferson, Phelps, Reynolds, St. Louis, Texas, and Washington counties. Found in the northeast corner of the Ozark Highlands, the Meramec River and its tributaries drain 2,149 square miles. -

Missouri Master Naturalist a Summary of Program Impacts and Achievements During 2017

Missouri Master Naturalist A summary of program impacts and achievements during 2017 Robert A. Pierce II Syd Hime Extension Associate Professor Volunteer and Interpretive Programs Coordinator and State Wildlife Specialist Missouri Department of Conservation University of Missouri 1 “The mission of the Missouri Master Naturalist program is to engage Missourians in the stewardship of the state’s natural resources through science-based education and community service.” Introduction Program Objectives The Missouri Master Naturalist program results 1. Improve public understanding of natural from a partnership created in 2004 between the resource ecology and management by Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) developing a pool of local knowledge that and University of Missouri Extension. These can be used to enhance and expand two organizations are the sponsors of the educational efforts within local communities program at the state level. Within MU Extension, the Missouri Master Naturalist 2. Enhance existing natural resources Program has the distinction of being recognized education and outreach activities by as a named and branded educational program. providing natural resources training at the The MU School of Natural Resources serves as local level, thereby developing a team of the academic home for the program. dedicated and informed volunteers The program is jointly administered by state 3. Develop a self-sufficient Missouri Master coordinators that represent the MDC and MU Naturalist volunteer network through the Extension. The state program coordinators Chapter-based program. provide leadership in conducting the overall program and facilitate the development of An increasing number of communities and training and chapter development with Chapter organizations across the state have relied on Advisors representing both organizations as these skilled volunteers to implement natural interest is generated within a local community. -

2016 St. Louis Region Southern Small River Accesses Area Plan Page 3

2016 St. Louis Region Southern Small River Accesses Area Plan Page 3 OVERVIEW Area Area Year Acreage County Division with River Number Acquired Maintenance & Administrative Responsibilities Allenton Access 6807 1969 9.8 St. Louis Forestry Meramec Campbell 8402 *1983 10.0 Crawford Forestry Meramec Bridge Access Chouteau Claim 7928 1979 15.0 Franklin Forestry Meramec, Access Bourbeuse Mammoth 6815 1968 4.75 Jefferson Forestry Big River Access Mill Rock 7604 1976 10.1 Franklin Forestry Bourbeuse Access Riverview 6904 1969 5.6 Crawford Forestry Meramec Access Sand Ford 7707 1977 30.9 Franklin Forestry Meramec Access Sappington 8401 *1983 10.0 Crawford Forestry Meramec Bridge Access Uhlemeyer 9407 1993, 12.3 Franklin Forestry Bourbeuse Access 1998 Wenkel Ford 8225 1982 5.4 Franklin Forestry Bourbeuse Access *Leased to the state of Missouri from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Statements of Primary Purpose: A. Strategic Direction St. Louis Region Southern Small River Accesses are managed by the Missouri Department of Conservation (the Department) to provide access to the Meramec, Bourbeuse and Big Rivers; protect stream bank integrity; and provide compatible public recreational opportunities. B. Desired Future Condition The desired future condition is a natural landscape that protects the natural resources present, while providing compatible recreational opportunities for the public. C. Federal Aid Statements • Riverview Access, or a portion thereof, was developed with Land and Water Conservation Fund dollars to provide land or facilities for public outdoor recreation. 2016 St. Louis Region Southern Small River Accesses Area Plan Page 4 • Allenton Access and Mammoth Access, or a portion thereof, were acquired with Land and Water Conservation Fund dollars to provide land or facilities for public outdoor recreation. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Group Tour Manual

Group Tour GUIDE 1 5 17 33 36 what's inside 1 WELCOME 13 FUN FACTS – (ESCORT NOTES) 2 WEATHER INFORMATION 17 ATTRACTIONS 3 GROUP TOUR SERVICES 30 SIGHTSEEING 5 TRANSPORTATION INFORMATION 32 TECHNICAL TOURS Airport 35 PARADES Motorcoach Parking – Policies 36 ANNUAL EVENTS Car Rental Metro & Trolley 37 SAMPLE ITINERARIES 7 MAPS Central Corridor Metro Forest Park Downtown welcome St. Louis is a place where history and imagination collide, and the result is a Midwestern destination like no other. In addition to a revitalized downtown, a vibrant, new hospitality district continues to grow in downtown St. Louis. More than $5 billion worth of development has been invested in the region, and more exciting projects are currently underway. The Gateway to the West offers exceptional music, arts and cultural options, as well as such renowned – and free – attractions as the Saint Louis Art Museum, Zoo, Science Center, Missouri History Museum, Citygarden, Grant’s Farm, Laumeier Sculpture Park, and the Anheuser-Busch brewery tours. Plus, St. Louis is easy to get to and even easier to get around in. St. Louis is within approximately 500 miles of one-third of the U.S. population. Each and every new year brings exciting additions to the St. Louis scene – improved attractions, expanded attractions, and new attractions. Must See Attractions There’s so much to see and do in St. Louis, here are a few options to get you started: • Ride to the top of the Gateway Arch, towering 630-feet over the Mississippi River. • Visit an artistic oasis in the heart of downtown. -

Add 30 SEW Premium Sites Add 6 Two-Bedroom Cabins and Renovate Existing 12 Room Lodge Replace 6 Basic Sites with 6 Camper Cabins

Park/Site Project Cost (excluding FFE) Scope of Work Convert 28 Campsites to Sewer/Electric/Water premium sites, and connect the wastewater system to Mound Convert 28 campsites (numbers 49-76) to sites that offer 50 amp, sewer and water Big Lake State Park City/Craig $ 3,010,343 connections; connect wastewater system to Mound City/Craig Construct a new campground loop with 30 campsites next to existing Sewer/Electric/Water campground loop. Each campsite will have sewer, 50 amp Cuivre River State Park Add 30 SEW Premium Sites $ 2,327,162 electricity and water connections. Rehabilitate the existing 12 room lodge by replacing dormitory wing, upgrading Add 6 Two-Bedroom Cabins and Renovate Existing kitchen/dining area and making some structural repairs to the building. Build adequate Current River State Park 12 room lodge $ 9,900,029 electric, water, and sewer service. Add 6 full service, two bedroom cabins by lake. Dr. Edmund A. Babler State Park Convert 35 sites to SEW Premium Sites $ 2,316,766 Convert 35 (1-33, 37 & 38) sites to SEW Premium Sites Dr. Edmund A. Babler State Park Renovate Babler Lodge $ 3,170,264 Renovate lodge Construct six new cabins (2 four bedroom, 4 two bedroom) in part of the existing day use Echo Bluff State Park Add 2 Four-Bedroom Cabins and 4 Two-Bedroom Cabins $ 3,011,901 area. Add 20 new campsites that offer 50 AMP electric service, and connections for sewer and Finger Lakes State Park Add 20 SEW Premium Sites $ 2,504,654 water; cost includes upgrading the wastewater system Modify six existing basic campsites by placing camper cabins on the sites. -

03-05 Heritage Issue.Pmd

Volume 21, No. 2 May, 2003 Bonnie Stepenoff, Editor Most Threatening Bills Stopped Back to the Current In 2003 State Legislature by John Karel by David Bedan, MPA Legislative Chair The official slogan these days of Current trends in the Missouri ended on May 16, nearly all of the our Division of Tourism is General Assembly are very worst bills were defeated. Some “Missouri...Where the Rivers disturbing for anyone concerned of the worst were defeated in the Run”. Although most such slogans about the conservation of Senate on the last day of the are largely salesmanship, this one Missouri’s natural resources. legislative session. The most happens to be a bona fide Dozens of bills and budgetary damaging bills that passed related reflection of the central role of proposals were introduced which to DNR’s General Revenue freshwater streams in the human would have rolled back the gains Budget and to its earmarked and natural history of our in environmental protection and environmental funds. crossroads state. From the continent-draining giants of the the conservation of natural Cuts to DNR’s Budget Missouri and Mississippi, to the resources that Missourians have rivulets of clean clear water made over the last 30 years. The budget process is being bubbling from thousands of hidden Some of these bills threatened the used to drastically weaken the springs, Missouri’s rivers and Missouri Division of Parks; others DNR which is responsible for the streams have defined our would have weakened the implementation of most of landscapes, shaped our vegetation Missouri Department of Natural Missouri’s existing environmental and wildlife, and determined the Resources (DNR) and the protection laws. -

House Bill No. 19

FIRST REGULAR SESSION SENATE COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTE HOUSE COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTE FOR HOUSE BILL NO. 19 101ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY 0019S.03C AN ACT To appropriate money for the several departments and offices of state government, and the several divisions and programs thereof, for planning and capital improvements including but not limited to major additions and renovations, new structures, and land improvements or acquisitions, to be expended only as provided in Article IV, Section 28 of the Constitution of Missouri for the fiscal period beginning July 1, 2021 and ending June 30, 2022. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the state of Missouri, as follows: There is appropriated out of the State Treasury, to be expended only as provided in 2 Article IV, Section 28 of the Constitution of Missouri, for the purpose of funding each 3 department, division, agency, and program described herein for the item or items stated, and for 4 no other purpose whatsoever, chargeable to the fund designated for the period beginning July 1, 5 2021 and ending June 30, 2022, as follows: Section 19.005. To the Department of Natural Resources 2 For the Division of State Parks 3 For state park and historic site capital improvement expenditures, 4 including design, construction, renovation, maintenance, repairs, 5 replacements, improvements, adjacent land purchases, installation 6 and replacement of interpretive exhibits, water and wastewater 7 improvements, maintenance and repair to existing roadways, 8 parking areas, and trails, acquisition, restoration, and marketing of 9 endangered historic properties, and expenditure of recoupments, 10 donations, and grants 11 From Department of Natural Resources Federal Fund (0140). -

Missouri Master Naturalist a Summary of Program Impacts and Achievements During 2019

Missouri Master Naturalist A summary of program impacts and achievements during 2019 “The mission of the Missouri Master Naturalist program is to engage Missourians in the stewardship of the state’s natural resources through science-based education and community service.” Introduction Program Objectives The Missouri Master Naturalist program results 1. Improve public understanding of natural from a partnership created in 2004 between the resource ecology and management by Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) developing a pool of local knowledge that and University of Missouri Extension. These can be used to enhance and expand two organizations are the sponsors of the educational efforts within local communities program at the state level. Within MU Extension, the Missouri Master Naturalist 2. Enhance existing natural resources Program has the distinction of being recognized education and outreach activities by as a named and branded educational program. providing natural resources training at the The MU School of Natural Resources serves as local level, thereby developing a team of the academic home for the program. dedicated and informed volunteers The program is jointly administered by state 3. Develop a self-sufficient Missouri Master coordinators that represent the MDC and MU Naturalist volunteer network through the Extension. The state program coordinators Chapter-based program. provide leadership in conducting the overall program and facilitate the development of An increasing number of communities and training and chapter -

White River Forum II: Second Annual Meeting of the White River Forum John Havel

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Technical Reports Arkansas Water Resources Center 11-2-2009 White River Forum II: Second Annual Meeting of the White River Forum John Havel Kenneth Steele Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/awrctr Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, Hydrology Commons, Soil Science Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Havel, John and Steele, Kenneth. 2009. White River Forum II: Second Annual Meeting of the White River Forum. Arkansas Water Resources Center, Fayetteville, AR. MSC287. 28 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Arkansas Water Resources Center at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ~~ White River Forum II ABSTRACTS Technical Session: Water Quality and Conservation Issues in the White River Basin Mountain Home, Arkansas November 2, 2000 94. 93" 92. LAKE TANEYCOMO / r - 36" \., - MISSOURI ' r--f.TVOV LJAIIIA ARKANSAS 0 10 20 MILES 6 16 I to ~LOMETERS (map pro••ided b) USGS) Publication No. MSC-287 Arka nsas Water Resources Center 112 Ozark Ball University of Ar kansas Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701 White River Forum II Mountain Home, Arkansas Nov 2, 2000 Technical Session: Water Quality and Conservation Issues in the White River Basin Preface This second annual meeting of the White River Forum is proof of widespread interest in the water quality of the Upper White River watershed. The participation of numerous elected officials, state and federal agencies, universities, businesses, and local citizens indicates that interest in understanding policy issues crosses political boundaries and occupations.