The Truth About Life, Sung Like a Lie: Dylan's Timeless Arrows From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midwestern Isolationist

Journal of American Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS Additional services for Journal of American Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Bringing It All Back Home or Another Side of Bob Dylan: Midwestern Isolationist Tor Egil Førland Journal of American Studies / Volume 26 / Issue 03 / December 1992, pp 337 - 355 DOI: 10.1017/S0021875800031108, Published online: 16 January 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S0021875800031108 How to cite this article: Tor Egil Førland (1992). Bringing It All Back Home or Another Side of Bob Dylan: Midwestern Isolationist. Journal of American Studies, 26, pp 337-355 doi:10.1017/S0021875800031108 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS, IP address: 138.251.14.35 on 17 Mar 2015 Bringing It All Back Home or Another Side of Bob Dylan: Midwestern Isolationist TOR EGIL F0RLAND The subject of this article is the foreign policy views of singer and songwriter Bob Dylan: a personality whose footprints during the 1960s were so impressive that a whole generation followed his lead. Today, after thirty years of recording, the number of devoted Dylan disciples is reduced but he is still very much present on the rock scene. His political influence having been considerable, his policy views deserve scrutiny. My thesis is that Dylan's foreign policy views are best characterized as "isolationist." More specifically: Dylan's foreign policy message is what so-called progressive isolationists from the Midwest would have advocated, had they been transferred into the United States of the 1960s or later. -

Diplomarbeit Der Utopiediskurs in Der Amerikanischen, Postapokalyptischen Serie the Walking Dead

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Der Utopiediskurs in der amerikanischen, postapokalyptischen Serie The Walking Dead“ verfasst von Doris Kaminsky angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 313 333 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium UniStG UF Geschichte, Sozialkunde und Politische Bildung UniStG UF Deutsch UniStG Betreut von: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Frank Stern Danksagung Zuerst möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei meinem Betreuer Dr. Frank Stern bedanken, der mir auch in schwierigen Phasen aufmunternde Worte zugesprochen hat und mit zahlreichen Tipps und Anregungen immer an meiner Seite stand. Zudem will ich mich auch bei Herrn Professor Dr. Stefan Zahlmann M.A. bedanken, der durch seine anregenden Seminare meine Themenfindung maßgeblich beeinflusst hat. Großer Dank gebührt auch meinen Eltern, die immer an mich geglaubt haben und auch in dieser Phase meines Lebens mit tatkräftiger Unterstützung hinter mir standen. Außerdem möchte ich mich auch bei meinen Freunden bedanken, für die ich weniger Zeit hatte, die aber trotzdem zu jeder Zeit ein offenes Ohr für meine Probleme hatten. Ein besonderer Dank gilt auch meinem Freund Wasi und Wolf, die diese ganze Arbeit mit sehr viel Sorgfalt gelesen und korrigiert haben. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung........................................................................................................ 1 2. Utopie, Eutopie und Dystopie................................................................ 4 2.1 Definition und Merkmale der Utopie.............................................. 5 2.2 Vom Raum zur Zeit: eine kurze Geschichte der Utopie.................. 7 2.2 Die Utopie im Medium Film und Fernsehen................................... 9 3. „Zombie goes global“ – Der Zombieapokalypsefilm und der utopische Impuls.................... 11 3.1 Vom Horror zur Endzeit – Das Endzeitszenario und der Zombiefilm.................................... 12 3.1.1 Das Subgenre Endzeitfilm und die Abgrenzung vom Horrorgenre...... -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Post-Presidential Speeches

Post-Presidential Speeches • Fort Pitt Chapter, Association of the United States Army, May 31, 1961 General Hay, Members of the Fort Pitt Chapter, Association of the United States Army: On June 6, 1944, the United States undertook, on the beaches of Normandy, one of its greatest military adventures on its long history. Twenty-seven years before, another American Army had landed in France with the historic declaration, “Lafayette, we are here.” But on D-Day, unlike the situation in 1917, the armed forces of the United States came not to reinforce an existing Western front, but to establish one. D-Day was a team effort. No service, no single Allied nation could have done the job alone. But it was in the nature of things that the Army should establish the beachhead, from which the over-running of the enemy in Europe would begin. Success, and all that it meant to the rights of free people, depended on the men who advanced across the ground, and by their later advances, rolled back the might of Nazi tyranny. That Army of Liberation was made up of Americans and Britons and Frenchmen, of Hollanders, Belgians, Poles, Norwegians, Danes and Luxembourgers. The American Army, in turn, was composed of Regulars, National Guardsmen, Reservists and Selectees, all of them reflecting the vast panorama of American life. This Army was sustained in the field by the unparalleled industrial genius and might of a free economy, organized by men such as yourselves, joined together voluntarily for the common defense. Beyond the victory achieved by this combined effort lies the equally dramatic fact of achieving Western security by cooperative effort. -

Michel Montecrossa Sings Bob Dylan and Related Artists

ETERNAL CIRLCE CD-PLUS AUDIO-TRACKS: 1. Eternal Circle 4:09 2. Knockinʻ On Heavenʻs Door 3:58 3. Sitting On A Barbed Wire Fence 6:59 4. Blowinʻ In The Wind 6:35 5. Mixed Up Confusion 4:25 6. Tomorrow Is A Long Time 4:58 7. Love Minus Zero / No Limit 4:19 8. On The Road Again 4:33 9. All Along The Watchtower 4:17 10. Bob Dylanʻs Dream 5:22 11. Couple More Years (From the movie Hearts of Fire) 1:53 MPEG-VIDEO 1. Quinn, The Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn) 4:14 (All songs Bob Dylan except Track 11) PICTURE-EVENTS INTERNETDATA P 1998 © Mira Sound Germany / MCD-266 BORN IN TIME CD-PLUS AUDIO-TRACKS: 1. Born In Time 5:41 2. The Groomʻs Still Waiting At The Altar 3:52 3. Quinn, The Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn) 3:48 4. Forever Young 2:55 5. Paths Of Victory 4:04 6. I And I 4:36 7. Dark Eyes 2:59 8. Political World 3:19 9. Can You Please Crawl Out Of Your Window 4:12 10. Angelina 3:58 11. Donʻt Think Twice Itʻs All Right 2:23 12. Like A Rolling Stone 5:50 13. Most Of The Time 3:28 14. Man In The Long Black Coat 3:55 15. Series Of Dreams 5:54 16. Lone Pilgrim (Traditional) 2:29 17. Abandoned Love 2:54 MPEG-VIDEO: 1. I Shall Be Released 2:43 (All songs Bob Dylan except Track 16) PICTURE-EVENTS INTERNETDATA P 1999 © Mira Sound Germany / MCD-301 Michel Montecrossa sings other Artists / Bob Dylan and related Artists – 1 E1 JET PILOT CD-PLUS AUDIO-TRACKS: 1. -

Political World of Bob Dylan

Digital Collections @ Dordt Faculty Work Comprehensive List 4-8-2016 Political World of Bob Dylan Jeff Taylor Dordt College, [email protected] Chad Israelson Rochester Community and Technical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work Part of the Christianity Commons, Music Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, J., & Israelson, C. (2016). Political World of Bob Dylan. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work/499 This Conference Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Work Comprehensive List by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political World of Bob Dylan Abstract According to Bob Dylan, we live in what his 1989 song calls a “Political World.” He is correct. But what does this mean? And what is Dylan’s relation to his world? Keywords Bob Dylan, American music, political views, social views, worldview Disciplines Christianity | Music | Politics and Social Change Comments Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association annual conference held in Chicago in April 2016. This paper is adapted from the Palgrave Macmillan book The Political World of Bob Dylan: Freedom and Justice, Power and Sin by Jeff Taylor and Chad Israelson. © 2015. All rights reserved. This conference presentation is available at Digital Collections @ Dordt: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/ faculty_work/499 MPSA Annual Conference – April 2016 The Political World of Bob Dylan by Jeff Taylor (and Chad Israelson) According to Bob Dylan, we live in what his 1989 song calls a “Political World.” He is correct. -

Bob Dylan Blind Willie Mctell

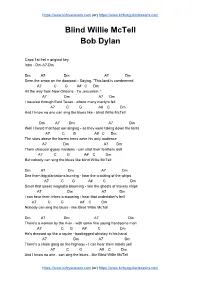

Blind Willie McTell Bob Dylan Seen the arrow on the doorpost Saying, "This land is condemned All the way from New Orleans To Jerusalem." I traveled through East Texas Where many martyrs fell And I know no one can sing the blues Like Blind Willie McTell Well, I heard the hoot owl singing As they were taking down the tents The stars above the barren trees Were his only audience Them charcoal gypsy maidens Can strut their feathers well But nobody can sing the blues Like Blind Willie McTell See them big plantations burning Hear the cracking of the whips Smell that sweet magnolia blooming (And) see the ghosts of slavery ships I can hear them tribes a-moaning (I can) hear the undertaker's bell (Yeah), nobody can sing the blues Like Blind Willie McTell There's a woman by the river With some fine young handsome man He's dressed up like a squire Bootlegged whiskey in his hand There's a chain gang on the highway I can hear them rebels yell And I know no one can sing the blues Like Blind Willie McTell Well, God is in heaven And we all want what's his But power and greed and corruptible seed Seem to be all that there is I'm gazing out the window Of the St. James Hotel And I know no one can sing the blues Like Blind Willie McTell Tištěno z pisnicky-akordy.cz Sponzor: www.srovnavac.cz - vyberte si pojištění online! Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

1990 Summer Festival Tour of Europe

1990 SUMMER FESTIVAL TOUR OF EUROPE JUNE 27 Reykjavik, Iceland Laugardalshöll 29 Roskilde, Denmark Roskilde Rock Festival, Dyrskuepladsen 30 Kalvøya, Sandvika, Norway Kalvøya-Festivalen JULY 1 Turku, Finland Ruisrock, Ruissalon Kansanpuisto 3 Hamburg, Germany Stadtpark 5 Berlin, Germany Internationales Congress Centrum 7 Torhout, Belgium Torhout-Werchter Rock Festival 8 Werchter, Belgium Torhout-Werchter Rock Festival 9 Montreux, Switzerland Montreux Jazz Festival, Casino de Montreuz Bob Dylan 1990: Summer Festival Tour of Europe 11210 Laugardalshöll Reykjavik, Iceland 27 June 1990 1. Subterranean Homesick Blues 2. Ballad Of A Thin Man 3. Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again 4. Just Like A Woman 5. Masters Of War 6. Gotta Serve Somebody 7. It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding) 8. It's All Over Now, Baby Blue 9. Girl From The North Country 10. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall 11. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right 12. Everything Is Broken 13. Political World 14. All Along The Watchtower 15. Shooting Star 16. I Shall Be Released 17. Like A Rolling Stone — 18. Blowin' In The Wind 19. Highway 61 Revisited Concert # 202 of The Never-Ending Tour. First concert of the 1990 Summer Festival Tour Of Europe. 1990 concert # 32. Concert # 124 with the second Never-Ending Tour band: Bob Dylan (vocal & guitar), G. E. Smith (guitar), Tony Garnier (bass), Christopher Parker (drums). 7-11, 18 acoustic with the band. 2, 4, 8, 9, 11, 15, 18 Bob Dylan harmonica. 19 G.E. Smith (electric slide guitar). Note. First acoustic Hard Rain with the band. -

Blind Willie Mctell Bob Dylan

https://www.kirbyscovers.com (or) https://www.kirbysguitarlessons.com Blind Willie McTell Bob Dylan Capo 1st fret = original key Intro - Dm-A7-Dm Dm A7 Dm A7 Dm Seen the arrow on the doorpost - Saying, "This land is condemned A7 C G A# C Dm All the way from New Orleans - To Jerusalem." A7 Dm A7 Dm I traveled through East Texas - where many martyrs fell A7 C G A# C Dm And I know no one can sing the blues like - blind Willie McTell Dm A7 Dm A7 Dm Well I heard that hoot owl singing - as they were taking down the tents A7 C G A# C Dm The stars above the barren trees were his only audience A7 Dm A7 Dm Them charcoal gypsy maidens - can strut their feathers well A7 C G A# C Dm But nobody can sing the blues like blind Willie McTell Dm A7 Dm A7 Dm See them big plantations burning - hear the cracking of the whips A7 C G A# C Dm Smell that sweet magnolia blooming - see the ghosts of slavery ships A7 Dm A7 Dm I can hear them tribes a-moaning - hear that undertaker's bell A7 C G A# C Dm Nobody can sing the blues - like Blind Willie McTell Dm A7 Dm A7 Dm There's a woman by the river - with some fine young handsome man A7 C G A# C Dm He's dressed up like a squire - bootlegged whiskey in his hand A7 Dm A7 Dm There's a chain gang on the highway - I can hear them rebels yell A7 C G A# C Dm And I know no one - can sing the blues - like Blind Willie McTell https://www.kirbyscovers.com (or) https://www.kirbysguitarlessons.com https://www.kirbyscovers.com (or) https://www.kirbysguitarlessons.com Break - Dm-A7-Dm … Dm-A7-Dm … Dm-A7-C-G-A#-C-Dm Dm A7 Dm A7 Dm Well God is in heaven - and we all want what's his A7 C G A# C Dm But power and greed and corruptible seed - seem to be all that there is A7 Dm A7 Dm I'm gazing out the window - of the St. -

Dignity and the Nobel Prize: Why Bob Dylan Was the Perfect Choice

Dignity and the Nobel Prize: Why Bob Dylan Was the Perfect Choice Michael L. Perlin, Esq. Professor Emeritus of Law Founding Director, International Mental Disability Law Reform Project Co-founder, Mental Disability Law and Policy Associates New York Law School 185 West Broadway New York, NY 10013 212-431-2183 [email protected] [email protected] This paper is adapted from Tangled Up In Law : The Jurisprudence of Bob Dylan, 38 FORD. URB. L.J. 1395 (2011), reprinted in part, in in PROFESSING DYLAN 42 (Frances Downing Hunter ed. 2016). In awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1969, the Nobel Committee referred to the motto enshrined in the foundations of the ILO's original building in Geneva, "Si vis pacem, cole justitiam" - "If you desire peace, cultivate justice." When Elie Weisel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, he said, in his acceptance speech, “When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant.” Just last year, when Svetlana Alexievich was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the journal Independence wrote, “Nobel Prize is a symbol of fighting for human dignity and freedom! Free soul and literature always combating with dictatorship!" I share this with you, because there is a theme in Nobel Prize choices, in both the peace and the literature categories: dignity and justice. I believe that the Michael Perlin, 2016 Why Bob Dylan Was the Perfect Choice 2 selection of Bob Dylan as this year’s Nobel Prize winner in literature perfectly reflects both of these themes. -

The Walking Dead Season 2 Episode 13 Eng Sub

The walking dead season 2 episode 13 eng sub Rick and Carl return from the woods to find the farm in jeopardy. The group is split up in the ensuing chaos. With things looking grim, Rick's leadership is. The cast of The Walking Dead explore the challenges and changes their characters face in the conclusion of. The Walking Dead Season 2 () - Telltale Games Detailbeschreibung: http://haidycom/p/twd2. Live The Walking Dead: Season 1 Episode 1 - Walkthrough [ ENG - SUB ITA Jun the Apr 13, Best online movies and TV series in high quality HD - %. Drama · As the farm is overrun by walkers, the group fights to escape. The Walking Dead (–). /10 Season 2 | Episode 13 . Language: English. The Walking Dead - Season 2 The second season begins with Rick and his group of survivors leaving Atlanta. They decide Episode: 13/13 eps. Duration: The Walking Dead season seven is now into its final furlong with only While the latest episode - titled 'Say Yes' (read our review here) - was a. watch full episode @ The Walking Dead season 2 episode 13 full episode part 1 2x After spending the past few weeks on the Alexandrians' efforts to organize an alliance to battle the Saviors, the show spent Sunday with the. The Walking Dead season 7 episode 13 recap: It's all up to Morgan The Walking Dead turned its gaze toward Morgan and Carol in the Kingdom . Destiny 2 may be found in Warframe · Batman: The Animated Series being. The cold open for this week's particularly strong episode made for startling television. -

The Jurisprudence of Bob Dylan, 38 Fordham Urb

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 38 Article 9 Number 5 Symposium - Bob Dylan and the Law 2012 Tangled Up In Law: The urJ isprudence of Bob Dylan Michael L. Perlin New York law School Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Recommended Citation Michael L. Perlin, Tangled Up In Law: The Jurisprudence of Bob Dylan, 38 Fordham Urb. L.J. 1395 (2012). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol38/iss5/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tangled Up In Law: The urJ isprudence of Bob Dylan Cover Page Footnote Director, International Mental Disability Law Reform Project; Director, Online Mental Disability Law Program, New York Law School. The uthora wishes to thank Kaydi Osowski for her superb research help. This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol38/iss5/9 PERLIN_CHRISTENSEN 1/30/2012 10:10 AM TANGLED UP IN LAW: THE JURISPRUDENCE OF BOB DYLAN Michael L. Perlin* Introduction ........................................................................................... 1395 I. Civil Rights ...................................................................................... 1399 II. Inequality of the Criminal Justice System .................................. 1404 III. Institutions .................................................................................... 1411 IV. Governmental/Judicial Corruption ........................................... 1415 V. Equality and Emancipation ......................................................... 1417 VI. Poverty, Environment, and Inequality of the Civil Justice System .......................................................................................... 1424 VII.