The Challenge of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kings of Israel & Judah

THE KINGS OF ISRAEL AND JUDAH 1 2 THE KINGS OF ISRAEL AND JUDAH Verse by Verse Notes Jim Cowie 3 Printed by: Stallard & Potter 2 Jervois Street Torrensville South Australia 5031 Published by: Christadelphian Scripture Study Service 85 Suffolk Road Hawthorndene South Australia 5051 Fax + 61 8 8271–9290 Phone (08) 8278–6848 Email: [email protected] November 2002 4 PREFACE . B. N. Luke 2002 5 6 CONTENTS Page Introduction 10 Israel’s First Three Kings - Saul, David, and Solomon 15 Map of the Divided Kingdom Rehoboam - The Indiscreet (Judah) Jeroboam - The Ambitious Manipulator (Israel) Abijah - The Belligerent (Judah) Asa - Judah’s First Reformer (Judah) The Chronological Data of the Kings of Israel Nadab - The Liberal (Israel) Baasha - The Unheeding Avenger (Israel) The Chronological Data of the Kings of Judah Elah - The Apathetic Drunkard (Israel) Zimri - The Reckless Assassin (Israel) Omri - The Statute-maker (Israel) Ahab - Israel’s Worst King (Israel) Ahab of Israel and Jehoshaphat of Judah Jehoshaphat - The Enigmatic Educator (Judah) Ahaziah - The Clumsy Pagan (Israel) Jehoram - The Moderate (Israel) Jehoram of Israel and Jehoshaphat of Judah Jehoram - The Ill-fated Murderer (Judah) Ahaziah - The Doomed Puppet (Judah) Jehu - Yahweh’s Avenger (Israel) Athaliah - “That wicked woman” (Judah) Joash - The Ungrateful Dependant (Judah) Amaziah - The Offensive Infidel (Judah) Jehoahaz - The Oppressed Idolater (Israel) Jehoash - The Indifferent Deliverer (Israel) Jeroboam - The Militant Restorer (Israel) Uzziah - The Presumptuous Pragmatist -

PRAISE and WORSHIPPERS

PRAISE and WORSHIPPERS Leen La Rivière Volume 3 in the series Biblical Principles 1 PRAISE & WORSHIPPERS Biblical principles for praise and worship ® Leen La Rivière 2 © Continental Sound/Christian Artists p.a. Continental Art Centre, P.O. Box 81065, 3009 GB Rotterdam, The Netherlands, [email protected], www.continentalsound.org; [email protected] First edition Copyright ISBN: ISBN: 978907695-9276 Distribution: Continental Sound Music, Rotterdam Typesetting: Lisanne de Vlieger Layout & design: Willem La Rivière Translation: Arachne van der Eijk Editing: Lindsay Jones With thanks to: CJR (Cultural Youth Council), Guido Verhoef, Gerard Bal, Hans Savert, Rev. Piet de Jong, Mirjam Feijer, Prof. Roel Kuiper. Scripture quotations taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society Used by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.. a member of the Hodder Headline Plc Group. All rights reserved “NIV” is a registered trademark of International Bible Society. UK trademark number 1448790. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilm or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Continental Sound/Christian Artists/CNV- Kunstenbond, with due regard to the exceptions laid down in the Copyright Act. This book is Volume 3 in the series Biblical Principles. 3 PREFACE Before you start reading this book, the following is worth noting. The usual approach to a book like this would be to consider what the life of a believer is like, what attitude a believer takes towards God and, on this basis, what attitude she/he takes to life. -

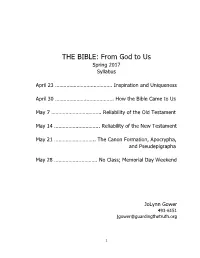

Syllabus and Text

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

Untimely Death of a Good King

Sunday School Lesson 2 Chronicles 35:20-27 by Lorin L. Cranford All rights reserved © Untimely Death of a Good King A copy of this lesson is posted in Adobe pdf format at http://cranfordville.com under Bible Studies in the Bible Study section A note about the blue, underlined material: These are hyperlinks that allow you to click them on and bring up the specified scripture passage automatically while working inside the pdf file connected to the internet. Just use your web browser’s back arrow or the taskbar to return to the lesson material. ************************************************************************** Quick Links to the Study I. Context II. Message a. Historical a. A Dumb Mistake, vv. 20-24a b. Literary b. Wrap up, vv. 24b-27 *************************************************************************** When a good leader is killed, what happens next? King Josiah of Judah from the time of his ascension to the throne in Jerusalem at the age of eight in 640 BCE sought to lead the nation in the ways of God. When he was sixteen years old he began a passionate quest to walk in God’s ways and to faithfully serve the God of Abraham. In the eighteen year of his reign (622 BCE) when he was twenty six years old the discovery of the “book of the Law of God” in the temple dramatically turned his life toward God. Thus from ap- proximately 640 to 609 BCE, the southern kingdom was led by a ruler with a deep desire to lead his country faithfully to serve God. Because of this religious devotion, God promised to spare him the coming agony of seeing his nation die in a horrible slaughter at the hands of the Babylonians after the turn of the century. -

Frameworks, Sounds and Imagery Motifs In

This work has been submitted to ChesterRep – the University of Chester’s online research repository http://chesterrep.openrepository.com Author(s): Gwendoline Mary Knight Title: Frameworks, cries and imagery in Lamentations 1-5: Working towards a cross- cultural hermeneutic Date: February 2011 Originally published as: University of Liverpool PhD thesis Example citation: Knight, G. M. (2011). Frameworks, cries and imagery in Lamentations 1-5: Working towards a cross-cultural hermeneutic. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Version of item: Submitted version Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10034/209452 FRAMEWORKS, CRIES AND IMAGERY IN LAMENTATIONS 1-5: Working Towards a Cross-cultural Hermeneutic Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Gwendoline Mary Knight FEBRUARY 2011 ABSTRACT Frameworks, Cries and Imagery in Lamentations 1-5: Working Towards a Cross-cultural Hermeneutic Gwendoline Mary Knight This thesis explores how the ancient Near Eastern Book of Lamentations can be read and interpreted cross-culturally today, so that the reader stays with the structure of the text but also listens to the spontaneity of cries from a bereft and humiliated people as they grapple with grief. The first part sets the scene and develops a hermeneutical model: a double-stranded helix, which demonstrates the tensions between the textual form and psychological content of Lamentations 1-5. The two strands are connected by three cross-strands, which represent frameworks, cries and metaphorical images introduced in the opening stanza of each lyric. In the second part, the model becomes the basis for an examination of the frameworks of the Lamentation lyrics and of psychological grief, which together demonstrate how regular patterns provide safe places from which to lament and grieve. -

Attribution of Lamentations to Jeremiah in Early Rabbinic Texts1

Acta Theologica 2009: 2 J. Kalman IF JEREMIAH WROTE IT, IT MUST BE OK: ON THE ATTRIBUTION OF LAMENTATIONS TO JEREMIAH IN EARLY RABBINIC TEXTS1 ABSTRACT Despite the absence of any formal attribution of the book of Lamentations to the prophet Jeremiah in the Hebrew Bible, the rabbis of the Talmudic period chose to perpetuate and reinforce this idea. The question explored is how this benefited them. Using Jorge Gracia’s discussion of the “pseudo-historical author,” the influence of the rabbinic as- sumption of Jeremiah’s authorship of Lamentations on their exegesis of the book is ex- plored. The rabbis were troubled by a number of theologically challenging verses and the claim of authorship opened the door to their use of the book of Jeremiah to explain away these difficulties. 1 In 2004 I was fortunate to enjoy a significant amount of time with Professor and Mrs. Riekert in Skukuza during the Rencontre Assyriologique and then while lecturing in Bloemfontein. Their overwhelming kindness and hospitality has not been forgotten and it is an honour to offer this article to Professor Riekert as a belated token of my gratitude and esteem. The argument put forward here was first presented at the symposiumLamentations: Music, Text, and Interpretation hosted by the Hebrew Union College-University of Cincinnati Ethics Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA on 21 February 2008. I am grate- ful to the organizers for the invitation to participate and to the discussants for their helpful feedback. All biblical citations unless otherwise indicated are quoted from the JPS Hebrew- English Tanakh (1999). -

Unsung Heroines of the Hebrew Bible: a Contextual Theological Reading from the Perspective of Woman Wisdom

UNSUNG HEROINES OF THE HEBREW BIBLE: A CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGICAL READING FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF WOMAN WISDOM BY FUNLOLA OLUSEYI OLOJEDE DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH FACULTY OF THEOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF OLD AND NEW TESTAMENT SUPERVISOR: PROF. HENDRIK L BOSMAN MARCH 2011 DECLARATION I the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree Signature……………………………………….. Date…………………………………………….. Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT This study is based primarily on the presupposition that the conventional definition or description of a biblical heroine does not take into account certain ‘hidden’ women in the Old Testament who could be distinguished due to their wisdom. By using the Yoruba woman as a contextual interpretive lens, the study investigates two female characters in the Old Testament each of whom is named in only one verse of Scriptures – “the First Deborah” in Genesis 35:8 and Sheerah in 1 Chronicles 7:24. The investigation takes its point of departure from the figure of Woman Wisdom of the book of Proverbs, which commentators have characterized as a metaphor for the Israelite heroine – a consummate image of the true Israelite female icon. It is indeed remarkable that Woman Wisdom has been associated with various female figures in the Old Testament such as Ruth, Abigail, the Wise Woman of Tekoa and the Wise Woman of Abel, etc. However, this study calls for a broader definition of wisdom based on the investigation of certain women in Old Testament narratives (e.g.