TV Outside The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Speakers and Chairs 2016

WEDNESDAY 24 FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE 09:30-09:45 10:00-11:00 BREAK BREAK 11:45-12:45 BREAK 13:45-14:45 BREAK 15:30-16:30 BREAK 18:00-19:00 19:00-21:30 20:50-21:45 THE SPEAKERS AND CHAIRS 2016 SA The Rolling BT “Feed The 11:00-11:20 11:00-11:45 P Edinburgh 12:45-13:45 P Meet the 14:45-15:30 P Meet the MK London 2012 16:30-17:00 The MacTaggart ITV Opening Night FH People Hills Chorus Beast” Welcome F Revealed: The T Breakout Does… T Breakout Controller: T Creative Diversity Controller: to Rio 2016: SA Margaritas Lecture: Drinks Reception Just Do Nothing Joanna Abeyie David Brindley Craig Doyle Sara Geater Louise Holmes Alison Kirkham Antony Mayfield Craig Orr Peter Salmon Alan Tyler Breakfast Hottest Trends session: An App Taskmaster session: Charlotte Moore, Network Drinks: Jay Hunt, The Superhumans’ and music Shane Smith The Balmoral screening with Thursday 14.20 - 14.55 Wednesday 15:30-16:30 Thursday 15:00-16:00 Thursday 11:00-11:30 Thursday 09:45-10:45 Wednesday 15:30-16:30 Wednesday 12:50-13:40 Thursday 09:45-10:45 Thursday 10:45-11:30 Wednesday 11:45-12:45 The Tinto The Moorfoot/Kilsyth The Fintry The Tinto The Sidlaw The Fintry The Tinto The Sidlaw The Networking Lounge 10:00-11:30 in TV Formats for Success: Why Branded Content BBC A Little Less Channel 4 Struggle For The Edinburgh Hotel talent Q&A The Pentland Digital is Key in – Big Cash but Conversation, Equality Playhouse F Have I Got F Winning in F Confessions of FH Porridge Adam Abramson Dan Brooke Christiana Ebohon-Green Sam Glynne Alex Horne Thursday 11:30-12:30 Anne Mensah Cathy -

The Fall Free

FREE THE FALL PDF Albert Camus,Robin Buss | 96 pages | 03 Aug 2015 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141187945 | English | London, United Kingdom The Fall | Netflix As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we The Fall six shows to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. At a Los Angeles hospital in the s, Alexandria is a child recovering from a broken arm. She befriends Roy Walker, a movie stunt man with legs paralyzed after a fall. At her request, Roy tells her an elaborate story about six men of widely varied backgrounds who are on a quest to kill a corrupt provincial governor. Between chapters of the story, Roy inveigles Alexandria to scout the hospital's pharmacy for morphine. As Roy's fantastic tale nears its end, Death seems close at hand. The Fall is an interesting movie with a variety of features such as mystery, suspense, violence, romance etc. It mixes reality with fantasy. I personally enjoyed the movie. Although it seems a little bit complicated to The Fall, this The Fall gives us a lesson of loyalty. It is amazing to see how two persons of different age develop a very strong friendship. The character of the little girl really The Fall my heart. She is an adorable actress; so cute and tender. The scenes have been filmed in very attractive The Fall all over the world. That is one reason by which people keeps interested thorough the whole movie. I personally recommend this movie to everyone. Looking for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and shows to round out your Watchlist. -

Masterpiece Theatre – the First 35 Years – 1971-2006

Masterpiece Theatre The First 35 Years: 1971-2006 Season 1: 1971-1972 The First Churchills The Spoils of Poynton Henry James The Possessed Fyodor Dostoyevsky Pere Goriot Honore de Balzac Jude the Obscure Thomas Hardy The Gambler Fyodor Dostoyevsky Resurrection Leo Tolstoy Cold Comfort Farm Stella Gibbons The Six Wives of Henry VIII ▼ Keith Michell Elizabeth R ▼ [original for screen] The Last of the Mohicans James Fenimore Cooper Season 2: 1972-1973 Vanity Fair William Makepeace Thackery Cousin Bette Honore de Balzac The Moonstone Wilkie Collins Tom Brown's School Days Thomas Hughes Point Counter Point Aldous Huxley The Golden Bowl ▼ Henry James Season 3: 1973-1974 Clouds of Witness ▼ Dorothy L. Sayers The Man Who Was Hunting Himself [original for the screen] N.J. Crisp The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club Dorothy L. Sayers The Little Farm H.E. Bates Upstairs, Downstairs, I John Hawkesworth (original for tv) The Edwardians Vita Sackville-West Season 4: 1974-1975 Murder Must Advertise ▼ Dorothy L. Sayers Upstairs, Downstairs, II John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Country Matters, I H.E. Bates Vienna 1900 Arthur Schnitzler The Nine Tailors Dorothy L. Sayers Season 5: 1975-1976 Shoulder to Shoulder [documentary] Notorious Woman Harry W. Junkin Upstairs, Downstairs, III John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Cakes and Ale W. Somerset Maugham Sunset Song James Leslie Mitchell Season 6: 1976-1977 Madame Bovary Gustave Flaubert How Green Was My Valley Richard Llewellyn Five Red Herrings Dorothy L. Sayers Upstairs, Downstairs, IV John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Poldark, I ▼ Winston Graham Season 7: 1977-1978 Dickens of London Wolf Mankowitz I, Claudius ▼ Robert Graves Anna Karenina Leo Tolstoy Our Mutual Friend Charles Dickens Poldark, II ▼ Winston Graham Season 8: 1978-1979 The Mayor of Casterbridge ▼ Thomas Hardy The Duchess of Duke Street, I ▼ Mollie Hardwick Country Matters, II H.E. -

Death and Nightingales”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RED ARROW STUDIOS INTERNATIONAL ACQUIRES DISTRIBUTION RIGHTS TO “DEATH AND NIGHTINGALES” MAJOR BBC DRAMA ADAPTED AND DIRECTED BY ALLAN CUBITT (“THE FALL”), PRODUCED BY THE IMAGINARIUM & SOHO MOON PICTURES LONDON. MAY 17, 2018: Red Arrow Studios INtErNatioNal has pickEd up the distribution rights to major NEw drama sEriEs “Death and Nightingales”, basEd on EugENE McCabE’s modErN Irish classic novEl. AdaptEd aNd dirEctEd by Allan Cubitt (“The Fall”), the 3 x 60’ drama sEriEs is aN ImagiNarium aNd Soho MooN PicturEs production for BBC Two. ImagiNarium’s JoNathan CavENdish (“ElizabEth: ThE GoldEN AgE”) is oN board to producE, with James MitchEll (“DrEams of a LifE”) for Soho MooN PicturEs and Tommy BulfiN (“PEaky BliNdErs”) for BBC Two as ExecutivE ProducErs. ThE sEriEs was commissionEd by Patrick HollaNd aNd PiErs WeNgEr, ControllEr of BBC Drama and is bEiNg supportEd by NorthErN IrElaNd ScrEEN. Red Arrow Studios INtErNatioNal will lauNch “Death and Nightingales” at MIPCOM 2018. McCabE’s “Death and Nightingales” is a rivetiNg story of love, betrayal, decEption and revENgE, sEt iN thE bEautiful, hauNtiNg couNtrysidE of Fermanagh, IrElaNd in 1885: a placE wherE NEighbours obsErvE Each other and iNform; a world of spiEs, coNfEssioNs and doublE dEaliNg; and whErE a pervading sEnsE of beauty is shot through with mEnacE and impENdiNg doom. Set ovEr a dEspEratEly tENsE 24-hour period, it is BEth WiNtErs’ 25th birthday - thE day shE has dEcidEd to joiN thE charmiNg Liam Ward aNd escape from hEr limited life aNd difficult aNd complex relatioNship with her ProtEstaNt laNdowNEr stEpfathEr, Billy. As dEcadEs of paiN aNd bEtrayal finally build to a devastating climax, this powErful and gripping drama illuminatEs tENsioNs that tEar both families aNd NatioNs apart. -

The Agency (London) Ltd – 2015

ALLAN CUBITT Writer Agent: Norman North In development: THE FALL Series 3 (Artists Studio / BBC N.I.) Writer/Director 5 x 60’ DEATH AND NIGHTINGALES (Caveman Pictures) Screenplay based on the novel by Eugene McCabe Film & Television: THE FALL Series 2 (Artists Studio / BBC N.I.) Writer/Director 6 x 60’ THE FALL Series 1 (Artists Studio / BBC N.I.) 5 x 60’ THE RUNAWAY (Company / Sky TV) 6 x 60' adaptation of Martina Cole novel THE BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN (Tiger Aspect Films) Director: Scott Hicks With Clive Owen MURPHY’S LAW Series 3 & 4 (Tiger Aspect / BBC) 5 Episodes SHERLOCK HOLMES - The Case of the Silk Stocking (Tiger Aspect / BBC) Director: Simon Cellan Jones With Rupert Everett SHERLOCK HOLMES – The Hound of the Baskervilles (Tiger Aspect / BBC) Director: David Attwood With Richard E. Grant DARWIN (WGBH) 60’ docu-drama ANNA KARENINA (Company Pictures/C4) Director: David Blair With Helen McCrory and Douglas Henshall PAINTED LADY (Granada TV) 4 hour original serial Director: Julian Jarrold With Helen Mirren ALL FOR LOVE (Little Bird Productions) Feature Film Director: Harry Hook THE HANGING GALE (Little Bird Productions/BBC) 4-part original serial PRIME SUSPECT II (Granada TV) Winner: Emmy Award for Outstanding Mini-Series 1993 Winner: Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best TV Mystery Feature or Mini Series 1993 Winner: Peabody Award 1993 THE COUNTESS ALICE Original Film Commission BBC: Producer Colin Ludlow Director: Moira Armstrong With Wendy Hiller, Zoe Wanamaker and Duncan Bell THE LAND OF DREAMS Original Film Commission BBC: Producer Colin Ludlow Director Diarmuid Lawrence With Partrick Shai, Antony Sher and Rudi Davies Winner: Intervision and Eurovision Award at the 28th Golden Prague Awards Theatre: THE POOL OF BETHESDA (Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond) Writer and Director Thames Television Bursary/Guildhall Winner: Thames Television Best Play and Best Production Awards for 1990 WINTER DARKNESS (New End Theatre, Hampstead) Writer Produced by Bristol Express Dir. -

Gender Dynamics in TV Series the Fall: Whose Fall Is It? Adriana Saboviková, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovakia1

Gender Dynamics in TV Series The Fall: Whose fall is it? Adriana Saboviková, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovakia1 Abstract This paper examines gender dynamics in the contemporary TV series The Fall (BBC 2013 - 2016). This TV series, through its genre of crime fiction, represents yet another way of introducing a strong female character in today’s postfeminist culture. Gillian Anderson’s Stella Gibson, a Brit and a woman, finds herself in the men’s world of the Police Service in Belfast, where the long shadow of the Troubles is still present. The paper proposes that the answer to the raised question - who the eponymous fall (implied in the name of the series) should be attributed to - might not be that obvious, while also discussing The Fall’s take on feminism embodied in its female lead. Keywords: female detectives, The Fall, TV crime drama, postfeminism Introduction Troubled history is often considered to be the reason for Northern Ireland being described as a nation of borderlines - not only obvious physical ones but also imagined. This stems from the conflict that has been described most commonly in terms of identities - based on culture, religion, and even geography. The conflict that has not yet been completely forgotten as the long shadow of the Troubles (local name, internationally known as the Northern Ireland conflict) is still present in the area. Nolan and Hughes (2017) describe Northern Ireland as “living apart together” separated by physical barriers. These locally called peace walls had to be erected to separate and, at the same time, protect the communities. -

30 October 2014

30 OCTOBER 2014 From November 14, BBC First brings Australian audiences the highly-anticipated second series of The Fall, express from the UK. Broadcasting just an hour after UK transmission, at 10am each week with an encore at 8.30pm, this highly anticipated second series is the first ‘express’ title from BBC First. The critically acclaimed psychological thriller sees the spectacular cast from series one return, with Gillian Anderson leading as Detective Superintendent Stella who is on the trail of serial murderer Paul Spector, played by BAFTA Award-winning actor and former model Jamie Dornan (Fifty Shades of Grey). Described as “one of the best crime thrillers of the past decade” (The Mirror), Australian viewers were left hanging at the end of series one with Spector fleeing Belfast and the case unresolved. The suspense mounts in the second series as the hunt for Spector continues. He becomes increasingly desperate as the net tightens around him and becomes psychologically ever more dangerous. Set in Belfast, Northern Ireland, The Fall Series Two is written and directed by Emmy® Award- winning Allan Cubitt and produced by Emmy Award-winning producer Gub Neal and Julian Stevens. The Fall – Series 2 Teaser Starring: Gillian Anderson (Hannibal, The X Files), Jamie Dornan (Fifty Shades of Grey, Once Upon a Time) The Fall Series Two premieres on BBC First from November 14 at 10am, an hour after UK transmission, with an encore at 8.30pm. Click to tweet: #TheFall S2 with Gillian Anderson & Jamie Dornan express to @BBCFirstAus from November 14. @GillianA ENDS Notes to Editors: For more information contact: Bryony Willis, Communications Executive, BBC Worldwide ANZ [email protected] T: +61 2 9744 4545 M: +61 413 255 920 To embed The Fall teaser please use this code: <iframe width="560" height="315" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/ussDH8OW0tM" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> A longer preview video will be available to embed early next week. -

Applying a Rhizomatic Lens to Television Genres

A THOUSAND TV SHOWS: APPLYING A RHIZOMATIC LENS TO TELEVISION GENRES _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by NETTIE BROCK Dr. Ben Warner, Dissertation Supervisor May 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the Dissertation entitled A Thousand TV Shows: Applying A Rhizomatic Lens To Television Genres presented by Nettie Brock A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________________________ Ben Warner ________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz ________________________________________________________ Stephen Klien ________________________________________________________ Cristina Mislan ________________________________________________________ Julie Elman ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Someone recently asked me what High School Nettie would think about having written a 300+ page document about television shows. I responded quite honestly: “High School Nettie wouldn’t have been surprised. She knew where we were heading.” She absolutely did. I have always been pretty sure I would end up with an advanced degree and I have always known what that would involve. The only question was one of how I was going to get here, but my favorite thing has always been watching television and movies. Once I learned that a job existed where I could watch television and, more or less, get paid for it, I threw myself wholeheartedly into pursuing that job. I get to watch television and talk to other people about it. That’s simply heaven for me. A lot of people helped me get here. -

Location Marketing and Cultural Tourism

Deliverable 4.1 Location marketing and cultural tourism Edited by Cathrin Bengesser Kim Toft Hansen Lynge Stegger Gemzøe WP number and title: WP4 – Creative Industries: Media Industries and location marketing strategies for a transcultural European space Task number and title: 4.1 and 4.2: “Understanding transnational European production and location strategies” & “Understanding pub- lishing and translation strategies in the European cultural space” Lead beneficiary: AAU Type: Report Dissemination level: Public Due date: Month 22 Actual date of delivery: 11 February 2020 2 This1 reportExecutive presents research Summaryinto location placement in Although the capitals of Europe still play a very im- popular cultural crime narratives across the European con- portant locative role in crime narratives and in popular cul- tinent. Considering the British, Nordic and South-Eastern ture in general, the report finds an increasing production European context, the report evaluates strategies in the interest in cities and places away from the central cities cultural, creative and tourism industries regarding the of Europe. Crime narratives have, to an increasing degree, choice of European locations and settings for local or trans- been able to profile rural areas, peripheral locations and national crime stories in literature, film and television. smaller towns for a potentially international audience. One the one hand, the report shows an increasing in- From Aberystwyth in Wales, to Ystad in Sweden, to Trieste ternational awareness from producers, funding schemes, in Italy, to Braşov in Romania, there is less attention to- distributors and broadcasters of both local and translocal wards cosmopolitan Europe and more interest in rural-ur- place branding in and through crime stories. -

Chris Corrigan

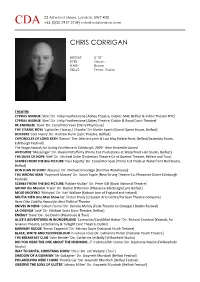

22 Astwood Mews, London, SW7 4DE CDA +44 (0)20 7937 2749|[email protected] CHRIS CORRIGAN HEIGHT: 5’10” EYES: Green HAIR: Brown SKILLS: Tenor; Guitar THEATRE CYPRUS AVENUE ‘Slim’ Dir. Vicky Featherstone [Abbey Theatre, Dublin; MAC Belfast & Public Theater NYC] CYPRUS AVENUE ‘Slim’ Dir. Vicky Featherstone [Abbey Theatre, Dublin & Royal Court Theatre] RE-ENERGIZE ‘Dave’ Dir. Conall Morrison [Derry Playhouse] THE TITANIC BOYS ‘Lightoller / Ismay / Chisolm’ Dir Martin Lynch [Grand Opera House, Belfast] DOCKERS ‘Jack Henry’ Dir. Andrew Flynn [Lyric Theatre, Belfast] CHRONICLES OF LONG KESH ‘Eamon’ Dirs. Martin Lynch & Lisa May [Waterfront, Belfast/Assembly Room, Edinburgh Festival] The Stage Awards for Acting Excellence in Edinburgh, 2009 - Best Ensemble Award ANTIGONE ‘Messenger’ Dir. Owen McCafferty [Prime Cut Productions at Waterfront Hall Studio, Belfast] THE DUKE OF HOPE ‘Mel’ Dir. Michael Duke [Tinderbox Theatre Co at Queens Theatre, Belfast and Tour] SCENES FROM THE BIG PICTURE ‘Paul Fogarty’ Dir. Conal Morrison [Prime Cut Prods at Waterfront Hall Studio, Belfast] DON JUAN IN SOHO ‘Aloysius’ Dir. Michael Grandage [Donmar Warehouse] THE WRONG MAN ‘Raymond Massey’ Dir. Sarah Tipple [New Strung Theatre Co, Pleasance Dome Edinburgh Festival] SCENES FROM THE BIG PICTURE ‘Robbie Mullan’ Dir. Peter Gill [Royal National Theatre] GROUP the Musical ‘Frank’ Dir. Rachel O’Riordan [Pleasance Edinburgh/Lyric Belfast] MOJO MICKYBO ‘Mickybo’ Dir. Karl Wallace [Kabosh tour of England and Ireland] MILITIA MEN One Man Show Dir. Fintan Brady [Crescent Arts Centre/Partisan Theatre Company] Rene Otto Castilla Award for Best Political Theatre KNIVES IN HENS ‘Gilbert Horne’ Dir. Deirdre Molloy [Fada Theatre Co Donegal / Dublin Festival] LA CHUNGA ‘José’ Dir. -

Moira Armstrong

Women in TV: Moira Armstrong BFI’s annual strand highlighting the role of women behind the TV camera celebrates the television director’s 50 years in the industry Month long season includes screenings of Testament of Youth (1979) and The Girls of Slender Means (1975), plus a career interview on Tuesday 19 August Monday 23 June 2014, London. Throughout August BFI Southbank will pay tribute to the outstanding achievements of BAFTA award-winning television director Moira Armstrong with a dedicated season. A recent report from Directors UK, which analysed a decade’s worth of British TV, revealed a decline in the opportunities for women directors in drama, entertainment and comedy in particular. With this debate at the forefront of the industry, BFI Southbank’s annual strand showcasing the contribution made by women behind the camera provides an opportunity to highlight the work of key female drama director. Armstrong began directing in 1964; her early work embraced famous strands such as The Wednesday Play, but she is perhaps best known for Testament of Youth (1979), which will screen in its entirety as part of the season. This dramatization of the autobiography of Vera Brittain showed, through the eyes of one young girl, the effects of WWI on a whole generation. The series’ success was in no small measure due to Armstrong’s many talents as a director: impeccable casting; the ability to draw out great performances; an instinct for the deeply-human centre of the story while eschewing over-sentimentality; and a great visual eye. Another series that played perfectly to Armstrong’s strengths was The Girls of Slender Means (1975), adapted by Ken Taylor from the novel by Muriel Spark. -

Bfi Southbank Events Listings for September - October 2016

BFI SOUTHBANK EVENTS LISTINGS FOR SEPTEMBER - OCTOBER 2016 PREVIEWS Catch the latest film and TV alongside Q&As and special events Sonic Cinema Preview: One More Time With Feeling UK 2016. Dir Andrew Dominik. RT and cert tbc. Digital. Courtesy of Picturehouse Entertainment Join us for the first opportunity to hear ‘Skeleton Tree,’ the new album from Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. Originally a performance-based film, One More Time with Feeling evolved into something much more significant as Dominik (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford) delved into the tragic backdrop of the writing and recording of the album, offering a raw and honest portrayal of an artist trying to find his way through the darkness. THU 8 SEP 21:00 NFT1 Preview: The First Monday in May USA 2016. Dir Andrew Rossi. 91min. Digital. Cert tbc. Courtesy of Dogwoof This is the first public screening of the new documentary from Andrew Rossi (Page One: Inside the New York Times), which offers unprecedented behind-the-scenes access to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s most popular exhibition to date, ‘China: Through the Looking Glass.’ Featuring appearances from Anna Wintour, John Galliano, and Jean Paul Gaultier, this engaging, fast-paced film peels back the curtain to reveal the hard work and politics behind the glamour of the fashion and art worlds. FRI 23 SEP 18:15 NFT1 TV Preview: Inside No. 9 (series 3) + Q&A with actors Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith and producer Adam Tandy BBC 2016. Dirs Guillem Morales, Graeme Harper. With Steve Pemberton, Reece Shearsmith, Keeley Hawes, Jessica Raine.