C:\RZ\LIS Food Webs\LIS FOOD WEBS FINAL REPORT\Zajac Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backyard Food

Suggested Grades: 2nd - 5th BACKYARD FOOD WEB Wildlife Champions at Home Science Experiment 2-LS4-1: Make observations of plants and animals to compare the diversity of life in different habitats. What is a food web? All living things on earth are either producers, consumers or decomposers. Producers are organisms that create their own food through the process of photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is when a living thing uses sunlight, water and nutrients from the soil to create its food. Most plants are producers. Consumers get their energy by eating other living things. Consumers can be either herbivores (eat only plants – like deer), carnivores (eat only meat – like wolves) or omnivores (eat both plants and meat - like humans!) Decomposers are organisms that get their energy by eating dead plants or animals. After a living thing dies, decomposers will break down the body and turn it into nutritious soil for plants to use. Mushrooms, worms and bacteria are all examples of decomposers. A food web is a picture that shows how energy (food) passes through an ecosystem. The easiest way to build a food web is by starting with the producers. Every ecosystem has plants that make their own food through photosynthesis. These plants are eaten by herbivorous consumers. These herbivores are then hunted by carnivorous consumers. Eventually, these carnivores die of illness or old age and become food for decomposers. As decomposers break down the carnivore’s body, they create delicious nutrients in the soil which plants will use to live and grow! When drawing a food web, it is important to show the flow of energy (food) using arrows. -

Plants Are Producers! Draw the Different Producers Below

Name: ______________________________ The Unique Producer Every food chain begins with a producer. Plants are producers. They make their own food, which creates energy for them to grow, reproduce and survive. Being able to make their own food makes them unique; they are the only living things on Earth that can make their own source of food energy. Of course, they require sun, water and air to thrive. Given these three essential ingredients, you will have a healthy plant to begin the food chain. All plants are producers! Draw the different producers below. Apple Tree Rose Bushes Watermelon Grasses Plant Blueberry Flower Fern Daisy Bush List the three essential needs that every producer must have in order to live. © 2009 by Heather Motley Name: ______________________________ Producers can make their own food and energy, but consumers are different. Living things that have to hunt, gather and eat their food are called consumers. Consumers have to eat to gain energy or they will die. There are four types of consumers: omnivores, carnivores, herbivores and decomposers. Herbivores are living things that only eat plants to get the food and energy they need. Animals like whales, elephants, cows, pigs, rabbits, and horses are herbivores. Carnivores are living things that only eat meat. Animals like owls, tigers, sharks and cougars are carnivores. You would not catch a plant in these animals’ mouths. Then, we have the omnivores. Omnivores will eat both plants and animals to get energy. Whichever food source is abundant or available is what they will eat. Animals like the brown bear, dogs, turtles, raccoons and even some people are omnivores. -

Metagenomic Analysis Reveals Rapid Development of Soil Biota on Fresh Volcanic Ash Hokyung Song1, Dorsaf Kerfahi2, Koichi Takahashi3, Sophie L

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Metagenomic analysis reveals rapid development of soil biota on fresh volcanic ash Hokyung Song1, Dorsaf Kerfahi2, Koichi Takahashi3, Sophie L. Nixon1, Binu M. Tripathi4, Hyoki Kim5, Ryunosuke Tateno6* & Jonathan Adams7* Little is known of the earliest stages of soil biota development of volcanic ash, and how rapidly it can proceed. We investigated the potential for soil biota development during the frst 3 years, using outdoor mesocosms of sterile, freshly fallen volcanic ash from the Sakurajima volcano, Japan. Mesocosms were positioned in a range of climates across Japan and compared over 3 years, against the developed soils of surrounding natural ecosystems. DNA was extracted from mesocosms and community composition assessed using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Metagenome sequences were obtained using shotgun metagenome sequencing. While at 12 months there was insufcient DNA for sequencing, by 24 months and 36 months, the ash-soil metagenomes already showed a similar diversity of functional genes to the developed soils, with a similar range of functions. In a surprising contrast with our hypotheses, we found that the developing ash-soil community already showed a similar gene function diversity, phylum diversity and overall relative abundances of kingdoms of life when compared to developed forest soils. The ash mesocosms also did not show any increased relative abundance of genes associated with autotrophy (rbc, coxL), nor increased relative abundance of genes that are associated with acquisition of nutrients from abiotic sources (nifH). Although gene identities and taxonomic afnities in the developing ash-soils are to some extent distinct from the natural vegetation soils, it is surprising that so many of the key components of a soil community develop already by the 24-month stage. -

Nature's Garbage Collectors

R3 Nature’s Garbage Collectors You’ve already learned about producers, herbivores, carnivores and omnivores. Take a moment to think or share with a partner: what’s the difference between those types of organisms? You know about carnivores, which are animals that eat other animals. An example is the sea otter. You’ve also learned about herbivores, which only eat plants. Green sea turtles are herbivores. And you’re very familiar with omnivores, animals that eat both animals and plants. You are probably an omnivore! You might already know about producers, too, which make their food from the sun. Plants and algae are examples of producers. Have you ever wondered what happens to all the waste that everything creates? As humans, when we eat, we create waste, like chicken bones and banana peels. Garbage collectors take this waste to landfills. And after our bodies have taken all the energy and vitamins we need from food, we defecate (poop) the leftovers that we can’t use. Our sewerage systems take care of this waste. But what happens in nature? Sea otters and sea turtles don’t have landfills or toilets. Where does their waste go? There are actually organisms in nature that take care of these leftovers and poop. How? Instead of eating fresh animals or plants, these organisms consume waste to get their nutrients. There are three types of these natural garbage collectors -- scavengers, detritivores, and decomposers. You’ve probably already met (and maybe even eaten) a few of them. Scavengers Scavengers are animals that eat dead, decaying animals and plants. -

Decomposers and Composting

NEIGHBORHOOD DISCOVERY: Decomposers and Composting To help prepare for this investigation, watch the video Composting. https://www.cbf.org/news-media/multimedia/video/cbf-education-videos/composting.html Introduction Have you ever wondered what happens to the leaves, grass, and twigs that fall on the ground in your backyard? Or what happens to your food scraps when you throw them out? Decomposition Decomposition is the natural breakdown of organic materials. People have been able to harness this natural process of decomposition for their own benefits, for centuries, and this practice has been known as composting. Composting is practiced by individuals, schools, communities, and counties—do you know anyone that composts? Composting can’t happen without decomposers! Decomposers are organisms that break down dead organic matter. These organisms are commonly known as the “FBIs:” Fungi, Bacteria, Insects. Insects that you’ll find in your backyard investigation are also known as terrestrial macroinvertebrates. Macroinvertebrates Macroinvertebrates are small organisms that we can see with our “naked” eye and that do not have a backbone, unlike vertebrates, which do. Examples of terrestrial macroinvertebrates that you might find include snails, worms, ants, and spiders. These organisms play a very important role in ecosystems: they break down organic material that then provide nutrients for the entire food web. A food web is a complex interaction of food chains in a biological community. A food chain is the sequence, or order, in which energy as food is transferred from one group of organisms to another. 1. Can you think of any decomposers off the top of your head? List them here. -

Activity 1: Producers, Consumers, Decomposers

Food Webs: Interconnectedness of Organisms in Ecosystems Activity 1: Producers, Consumers, Decomposers Overview Students become “experts” and make a creative presentation about the different ecological roles of producers, consumers, and decomposers at local and global scales Key Question How do different organisms obtain energy they need to survive, grow, and reproduce? Objectives Students will investigate how different organisms obtain energy. Students will identify producers, consumers, and decomposers. Grade: 6-8 Time 45 minutes Location Classroom Materials Internet Access Science textbook, encyclopedias, and other print resources. Worksheet: “Food Web Roles: Expert Groups Worksheet” (attached) Culminating Activity Students will work in groups to create presentations about different ecological roles: producers, consumers, decomposers. Directions 1. Engage prior knowledge of ecological roles. ● Quickwrite: Ask students to answer the question: What did I eat for lunch today? ● Then, project, hold up images, or draw three organisms: one plant, one animal, and one fungus that can be found in their community. ● Students should then answer the same question for these three organisms. Ask a few students to share their responses. Each of these organisms obtains energy in a different way, which we will explore next. 2. Divide students in groups and assign terms to each group. Break students into small groups of 3-4 individuals and assign each one of the following groups to research: primary producer, consumer, decomposer, herbivore, omnivore, carnivore. Explain that they will do an “Each-one-teach-one” with each of these terms. 1 3. Have each research one ecological role. Have the groups spend 15 minutes using online and print resources to gather information about the ecological role. -

FOOD CHAIN GAME an Interactive, Fast-Paced Game to Learn About Connections in the Food Chain

FOOD CHAIN GAME An interactive, fast-paced game to learn about connections in the food chain Materials: • Laminated character cards (producer, herbivore, carnivore, decomposer) • Popsicle sticks • Clothes pins Instructions: • Describe the roles of producers, herbivores, carnivores and decomposers in the food chain. Producers are plants that produce their own food using energy from the sun through a process called photosynthesis. Consumers cannot make their own food so they need to eat producers (these consumers are called herbivores) or other consumers (these consumers are called carnivores). Decomposers are fungi and bacteria that break down organic material such as dead producers, herbivores and carnivores. • In most ecosystems there are far more producers than herbivores and far more herbivores than carnivores. • Explain that the teacher will play the role of sun, which gives energy to the producers so they can grow. • Hand out one character card to each student along with a clothespin, which can be used to attach the card to their clothing. • Hand out one popsicle stick to each student to represent one life. • Establish boundaries for the game (roughly half a soccer field). • Everyone spreads out evenly on the field to start the game. • Establish with the students a signal that means the game is over. Goals of the game: • Herbivores chase producers and try to tag them. • Carnivores chase herbivores and try to tag them. • Decomposers can tag everyone… their role is to turn everyone else back into soil! • (Suggestion: Start with only producers, herbivores, carnivores in the first round and then introduce decomposers in the second round.) Rules: • If an herbivore tags a producer, the producer must give their popsicle stick to the herbivore. -

Worms and Decomposers

Worms and Decomposers Overview: Students will learn about the role of earthworms in decomposition. Subject area: Science Grade level: 3rd-5th Next Generation Science Standards: 5-LS2 Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics 5.LS2.1 Develop a model to describe the movement of matter among plants, animals, decomposers, and the environment. Objectives: Students will be able to observe what earthworms eat, discuss decomposition and the role of decomposers, observe how earthworms fit into the food chain, and locate earthworm castings. Prep time: 30 minutes Lesson time: 30 minutes Teacher Background: Earthworms spend most of their time in the soil. They often move forward by taking the soil in front of them into their mouths and passing it through them and out again. Thus, essentially eating their way through the soil, earthworms extract the food value they need from the bits of decaying organic matter in the soil. Excreted waste is known as worm castings. (See attachment A.) Although earthworms are like other consumers in that they are unable to produce their own food, they are unlike in that they do not eat live organisms. Instead, they extract food energy from decaying organic matter (plants and animals that have died). In the process, they break down the organic matter into smaller parts. Having been physically broken down by the digestive system of an earthworm, the organic matter is now ready for a group of organisms called decomposers. Decomposers, such as bacteria and fungi, chemically break down the organic matter into nutrients such as Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium. The nutrients are then more available to the plants growing in the soil. -

Food Webs 5.9B

Food Webs 5.9B Imagine for a moment that you stay after school one day to clean up the classroom. While cleaning, you move some plants away from the sunny windows. A week later, you remember to move the plants back. You notice something strange has happened. Instead of standing upright, the plants appear to be leaning toward the windows! Why? Plants need sunlight to survive. If a plant is moved away from sunlight, special cells in the plant help it turn back toward the Sun. The Sun’s energy allows plants to produce their own food. Plants then use this food energy to grow and reproduce. But not all organisms can make their own food. How do those other organisms get their food energy? Do they get it from the Sun? Where do all food chains and food webs get their energy? All of the food energy that passes between organisms comes from the Sun. You might be wondering how this is possible. After all, humans can’t eat sunlight! Plants and other organisms that can use sunlight first absorb it and then use that energy to make their own food. That energy passes to other organisms that eat the plants. For example, grass uses sunlight to make food. A deer gets energy by eating the plants. After that, a wolf gets energy by eating the deer. The movement of food energy from one organism to another is called a food chain. Take a look at the food chain on the right. The arrows show how food energy is passed from one organism to the other. -

5Th the Ecosystem of the Forest

The Ecosystem of the Forest The Ecosystem of the Forest Even if it doesn’t look like it, all living things constantly interact with their environment. For instance, every time you take a breath, you get oxygen from the air, and every time you breathe back out, you release carbon dioxide into the world around you. Both oxygen and carbon dioxide are vital gases that different organisms can use. You, a human, need the oxygen for energy and need to get rid of the carbon dioxide, because it’s a waste matter. Just like us, all other organisms take something from their environment while putting waste back into it. When several kinds of organisms interact with each other in one particular area, it’s called an ecosystem. In the forest, living beings (plants, animals, insects, fungi and bacteria) all interact with each other and with the soil and water to form the forest’s specific kind of ecosystem. So, how does it work? Every organism in the forest can be put in one of three categories. Depending on which category they’re in, they’ll interact with each other and the forest’s resources in a different way. The categories are producer, decomposer and consumer. Let’s look at each one. Producers are living things that can make their own energy out of non‐living resources all around them like, oxygen and water. They’re also known as autotrophs. Autotrophs do not need to kill anything in order to eat. Plants and algae, for example, are producers. In the forest’s ecosystem, the trees, shrubs and moss are all producers. -

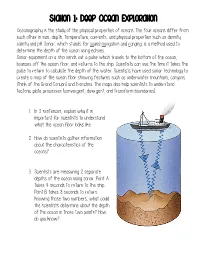

Station 1: Deep Ocean Exploration

Station 1: Deep Ocean Exploration Oceanography is the study of the physical properties of oceans. The four oceans differ from each other in size, depth, temperature, currents, and physical properties such as density, salinity and pH. Sonar, which stands for sound navigation and ranging, is a method used to determine the depth of the ocean using echoes. Sonar equipment on a ship sends out a pulse which travels to the bottom of the ocean, bounces off the ocean floor, and returns to the ship. Scientists can use the time it takes the pulse to return to calculate the depth of the water. Scientists have used sonar technology to create a map of the ocean floor showing features such as underwater mountains, canyons (think of the Grand Canyon) and trenches. The maps also help scientists to understand tectonic plate processes (convergent, divergent, and transform boundaries). 1. In 3 sentences, explain why it is important for scientists to understand what the ocean floor looks like. 2. How do scientists gather information about the characteristics of the oceans? 3. Scientists are measuring 2 separate depths of the ocean using sonar. Point A takes 4 seconds to return to the ship. Point B takes 8 seconds to return. Knowing those two numbers, what could the scientists determine about the depth of the ocean in those two points? How do you know? Station 2: Marine Life Forms Use the information in the passage below to fill in your chart. What living organisms are found in any one place in the ocean is determined by the environment at that place: temperature, pressure, and the amount of light in the water. -

Food Web Lesson Outline Grade Level: 3-5 Time: 45-60 Minutes

Food Web Lesson Outline Grade Level: 3-5 Time: 45-60 minutes NGSS Connections: PS3.D: Energy in Chemical Processes and Everyday Life-The energy released [from] food was once energy from the sun that was captured by plants in the chemical process that forms plant matter (from air and water). (5-PS3-1) LS2.A: Interdependent Relationships in Ecosystems- The food of almost any kind of animal can be traced back to plants. Organisms are related in food webs in which some animals eat plants for food and other animals eat the animals that eat plants. Organisms can survive only in environments in which their particular needs are met. A healthy ecosystem is one in which multiple species of different types are each able to meet their needs in a relatively stable web of life. Newly introduced species can damage the balance of an ecosystem. (5-LS2-1) Essential Question: How are salmon connected to forests? Materials: Printed food chain cards, food chain visuals, food web recording sheet for each student Objectives: Students will be able to… 1. Identify examples of producer, consumer, and decomposers 2. Organize a set of organisms into a food chain 3. Describe the cause and effect of adding and removing animals in a food web Vocabulary: food chain, food web, producer, consumer, decomposer Introduction (15min): Write the essential question (the class goal) on the board to refer back to at end of class. Introduce food chains by creating an example in the front of the classroom. Ask students to brainstorm local plants and animals that are part of the food chain starting with the sun.